Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Industrial Data

Print version ISSN 1560-9146On-line version ISSN 1810-9993

Ind. data vol.24 no.1 Lima Jan./Jun 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.15381/idata.v24i1.19858

Production and Management

Remote Work and Emotion Management in Times of COVID-19: A Perspective of Master’s Degree Students as Workers, Lima-Peru (2020)

1PhD in Administration and in Education from Universidad Nacional Federico Villareal (Lima, Peru). Currently working as professor at the same university. (Lima, Peru). E-mail: juribe@unmsm.edu.pe

2PhD in Nursing from Universidade Federal do Río de Janeiro (Rio de Janeiro, Brasil). Research professor at Universidad Cesar Vallejo. (Lima, Peru). E-mail: kmjimenez@ucv.edu.pe

3Master in Public Management. Currently working as professor at Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos. (Lima, Peru). E-mail: jvargasda@unmsm.edu.pe

4Master in Business Management. Currently working as an independent consultant. (Lima, Peru). E-mail: danielreydecastro@gmail.com

5Degree in Administration from Universidad Nacional Federico Villareal. Specialist in Human Capital Management. Currently working as consultant at the Ministerio Público del Perú. (Lima, Peru). E-mail: miguelj1528@gmail.com

6Master in Business Management and Administration. Currently working as professor at Universidad Peruana Unión. (Lima, Peru). E-mail: luis.geraldo@upeu.edu.pe

The main objective of this study is to determine the relationship between remote work and emotion management. It also aims to determine the relationship between the dimensions “working hours”, “work and technological support” and “social wellness”, and the emotion management variable. A methodology based on a quantitative approach with a descriptive-correlational and cross-sectional scope was used on a sample of 148 master’s degree students of the School of Administration of Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos. Likert-type scale surveys were used to gather data. The methods of analysis used were descriptive and correlational. The results indicate that the variables remote work and emotion management are positively and moderately correlated (0.465); therefore, it is concluded that remote work and all its dimensions are related to emotion management.

Key words: remote work; emotion management; master’s degree students; workers; COVID-19

INTRODUCTION

Humanity is currently experiencing a crisis as a result of the COVID-19 health emergency, which is defined by the World Health Organization as a pandemic (2020) that has changed the routine and daily life of people. The world of work as we conceive it has changed; in Europe, according to the International Labor Organization (ILO), “The most significant increase in teleworking took place in countries that were most affected by the virus, and where teleworking was well developed before the pandemic” (2020, p. 3); in Peru, legislation, albeit incipient, on teleworking already existed.

As of the first week of March 2020, data on the behavior of COVID-19 were available in Europe, mainly in Italy, France and Spain, where the pandemic was already leaving deadly consequences. In its chronology of COVID-19 performance on March 11, 2020, WHO reported that it was “Deeply concerned by the alarming levels of spread and severity, and by the alarming levels of inaction” and determined in its assessment that “COVID-19 can be characterized as a pandemic” (para. 20). From this date onwards, most of the world's governments adopted measures to prevent the spread of the virus in their countries.

In Peru, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, a Health Emergency was declared on March 11, 2020 throughout the national territory for a period of 90 calendar days through Supreme Decree No. 008-2020-SA. Likewise, under this legal norm, prevention and control measures were adopted for all sectors of public and private activity.

Therefore, the Peruvian Government, through Emergency Decree No. 026-2020, among other measures, established remote work in order to safeguard the safety and health of workers; consequently, a new way of working was established, different from what we were used to. This alarming situation, as of that official moment in the country, caused uncertainty in companies and forced them to rethink their processes in the midst of social isolation. In this regard, Juárez (2021) stated that COVID-19 “tomó a las organizaciones por sorpresa, en pleno proceso de implementación de su transformación digital, mientras que otras aún no tenían al trabajo remoto como una opción[took organizations by surprise, in the middle of their digital transformation, while others still had not yet considered remote work as an option]” (para. 2). This scenario ultimately became an irrefutable reality.

The ILO Convention 177 (1966) on home work is a precedent of telework and remote work, which established that home work refers to work performed at home or in any other place other than the one offered by the employer; in this context, workers receive remuneration, provide a service or produce a product according to the requirements of the employer, who is a legal person. This supranational standard urges States to protect all workers, i.e., to preserve all labor rights. It should be noted that the use of information and communication technologies is not mentioned in any of the provisions of the aforementioned agreement. To date, this agreement has only been ratified by ten countries, among which Peru is not included.

In this context, Eurofound and ILO (2019) in their report “Working anytime, anywhere: The effects on the world of work” present the results of a research carried out in 15 countries observed[15]; referring to telework/ICT-mobile work (T/ICTM)[16], they point out that ICT have revolutionized work and people's lives and have enabled real-time connection with families, as well as with immediate bosses and co-workers. They also consider that the negative aspect of this new way of working is “the encroachment of paid work into the spaces and times normally reserved for personal life” (p. 8); however, they also observe that technological advances are favorable for employees because they promote “spatial and temporal flexibility, in order to help them to balance work demands with their family and other personal responsibilities” (p.62). Similarly, the results of the T/ICTM are positive for the employers, as they allowed them to achieve better performance and optimize productivity.

Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) have transformed business activity as well as people’s lives. In developed countries, a significant progress had already been made regarding teleworking and other remote modalities; however, in countries such as Peru, where ICTs were still in their early stages of development, work systems had to be implemented according to their own reality. Under these circumstances, the Peruvian government opted to establish remote work.

At present, the terms telework and remote work are used interchangeably as if they had the same concept and application; nevertheless, they are different. Under Peruvian law, telework is regulated by Law No. 30036, D. S. No. 017-2015-TR, which essentially establishes that the acceptance of the worker is required for its implementation, work is subordinated and does not require the worker’s physical attendance. This regulation applies to the public and private sectors as it is a modality in which the labor relationship is maintained and carried out using ICT in its different formats, and the employer exercises labor control and supervision through it. Subordination is further evidenced by the provision of IT tools and other methods to assist in the performance of the function.

Conversely, remote work is regulated by Emergency Decree No. 026-2020 and its implementation is not freely chosen by the worker. The pandemic forced its implementation in order to prevent the spread of the disease among the population; for this reason, remote work is performed at the worker’s home or at the place of home isolation known by the employer. Accordingly, measures were adopted to guide employers to prevent affecting, among other aspects, the employment relationship and remuneration, and also to keep them informed on the health and safety measures to be followed. Guidelines on information security and confidentiality, compliance with health and safety measures in the place of isolation, and availability during the working hours were also issued for workers. As in teleworking, ICTs or other means are used for the fulfillment of functions insofar as permitted by their nature.

Remote work is thus a brand-new work system that emerged as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic and, to date, the effects or relationship between remote work and the management of workers' emotions are unknown, even though there are some studies and research related to teleworking and its effect on emotions.

Weller (2020), referring to telecommuting and teleworking in the context of the pandemic, observes that digitalization has assisted the labor scenario and has contributed to achieve “conciliación entre el trabajo y la vida familiar, la descongestión del tráfico urbano[work-life balance, and to reduce urban traffic congestion]” (p. 12); he further states that the increase of jobs supported by digitized platforms is expected at a global level. Weller (2020) and López (2020) agree that telecommuting in times of COVID-19 helps to prevent the spread of the pandemic in the workplace and, correspondingly, at home.

It is believed that as long as the pandemic continues, and probably after it, face-to-face work will be necessary in specific cases such as production centers, the agricultural industry, mines, among other economic activities; however, remote work is a modality that has not been discarded as a permanent option over time.

Peralta et al. (2020) analyze the impact of teleworking on companies as a result, primarily, of the advance of ICT. According to them, it has had an impact on the labor area and has forced companies to adopt new ways of working such as teleworking. They state that teleworking “rompe los esquemas tradicionales y genera en el teletrabajador mayor confianza en la organización y sentido de pertenencia, lo que persigue y consecuentemente espera una mayor productividad y eficiencia en los procesos administrativos[challenges traditional schemes and generates in the teleworker greater confidence in the organization and a sense of belonging, which is expected to increase productivity and efficiency in administrative processes]” (p. 9), something that can be achieved because this modality is part of labor flexibility.

A series of reflections on emotions in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic are provided by Johnson et al. (2020), who conclude that there is “la necesidad de diseñar estrategias para disminuir la incertidumbre con el objetivo de mejorar la salud de la población, considerando las desigualdades sociales y de género existentes[a need to design strategies to reduce uncertainty in order to improve the health of the population, taking into account existing social and gender inequalities]” (p. 2455). These reflections should be applied to all workers, regardless of the activity they carry out.

There is concern about the COVID-19 pandemic not only among governments, but also among international organizations such as WHO and ILO. Each has issued standards for governments to adopt according to their circumstances. Vulnerability is not the same in all countries, and the measures taken are based on scientific and technological advances.

In the publication of the supplement Día1 of the Peruvian newspaper El Comercio on remote work, Chávez (2021) reports positive results obtained by FutureLab on the management of emotions during this health emergency period. An important aspect addressed was the need for companies to ensure the safeguarding of the health of their employees’ families. This stance is also in line with the conclusions of an article recently published by Estrategias y Negocios (2021).

This research addresses two variables: remote work and emotion management. Remote work was approached considering the worker’s right to digital disconnection and to respect working hours (D. U. No. 127-2020); it was also analyzed based on three dimensions: working hours, work and technological support, and social wellness.

Working hours are understood as “el tiempo que cada trabajador dedica a la ejecución del trabajo para el que ha sido contratado. Esta jornada tiene un límite establecido por la Ley que es de 8 horas diarias o 48 horas semanales, como máximo[the time each worker devotes to the execution of the work for which he/she has been hired. By law, the limit of this working hours is established to be 8 hours a day or 48 hours a week, at most]” (Ministerio de Trabajo y Promoción del Empleo, 2019, p. 10); technological work support should be understood as support activities for workers managed by entities in times of pandemic and evidenced in guidelines for the optimal development of their functions, the transfer of information, technological programs, equipment and other tools that enable remote work. Finally, social wellness comprises activities aimed at creating an adequate work environment and a better quality of life for employees (MINJUS-SERVIR, 2016).

Analysis of emotional intelligence urges researchers to evoke the contributions of Gardner (2014), who considers that intelligences are intellectual capacities or domains that use specific skills for specific purposes, which gives rise to the theory of multiple intelligences. Based on this theory, and in particular on the types of intrapersonal and interpersonal intelligence, Salovey and Mayer (1990) first proposed the concept of emotional intelligence with emphasis on the cognitive processes of emotional evaluation and expression, as well as emotional regulation.

Regarding emotions in a critical pandemic situation, Ekman (2013) states that they are of valuable significance for life, because they allow us to feel pleasure and externalize joy, as well as to experience other types of feelings such as anger, hatred or jealousy; all of them, generated by external stimuli. As Cotrufo and Ureña (2018) pointed out, emotions have an extremely important function in changing contexts of crisis and uncertainty similar to those we are living in these times, and that is adaptation, as Charles Darwin stated in 1872 in a publication he titledThe Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals.

Under these circumstances, it is important to focus on the impact of the pandemic on emotions, as pointed out by Johnson et al. (2020) when they state that it is essential to concentrate on mental health “no solo para mejorar la salud sino también para evitar otros problemas sociales, tales como la estigmatización de personas, la falta de adherencia a medidas de prevención, y el duelo frente a la pérdida de seres queridos[not only to improve health but also to avoid other social problems, such as personal stigmatization, lack of adherence to prevention measures, and coping with grief at the loss of loved ones]” (p. 2448). They agree with Manucci (2017) that the development of people’s emotional capacity cannot be postponed, considering that people who perform remote work are no strangers to the emotional impact of the pandemic.

To understand emotional management, we must start by knowing what emotions are. Goleman (1996) stated that “emotions are, in essence, impulses to act, the instant plans for handling life that evolution has endowed instilled in us [...] suggesting that in every emotion there is an implicit tendency to act” (p.24), and that emotion “is any feeling, thought, psychological or biological state unique to it and a part of personal tendency to act accordingly” (p.331). He further noted that there are some primary emotions: anger, sadness, fear, pleasure, love, surprise, disgust, and shame. From neuroscience, Cotrufo and Ureña (2018) consider that emotions “son un conjunto de cambios que se dan a nivel fisiológicos, cognitivos, subjetivos y motores[are a set of changes that occur at physiological, cognitive, subjective and motor levels]” (p.18) and arise from a conscious or unconscious perception based on the circumstances and the concrete reality (stimuli) in which a person interacts.

According to Goleman (1996), self-awareness is the ability to recognize personal emotions and identify a feeling as it occurs; self-regulation consists of the ability of people to adequately channel their feelings, based on the awareness of their own being; and motivation is related to the ability to adequately structure emotions to better focus and prioritize objectives. In turn, empathy refers to the ability to recognize and understand others' emotions, which, in a way, allows people to adapt to crisis contexts such as the one caused by the coronavirus pandemic. Finally, social skills are related to the ability to properly manage interactions with others. Consequently, as noted in Gálvez (2017), emotional management is the ability of people to regulate emotions and adapt to changes that may occur in their environment of interaction.

This research therefore seeks to answer the following question: what is the relationship between remote work and emotion management? Its general objective is to determine the relationship between remote work and the management of emotions of the students of the Master in Administration with Mention in Human Resources Management, as workers in the public or private sector. It also aimed to determine the relationship between the dimensions of working hours, technological work support and social wellness, and the variable of emotion management.

The pandemic situation the world is going through has undoubtedly led to new forms of coexistence commonly known as the “new normal”, where physical distance is one of the fundamental rules. Most governments were forced to introduce remote work, a form of telecommuting imposed and implemented without a legal framework or sufficiently solid technological support in many countries, among them Peru. Thus, considering human capital as the most important intangible element in organizations, it is important to study the impact of remote work on workers on the basis of the fundamental dimensions for good work performance. This research explores a new and under-studied topic as a result of the rapid and surprising spread of the COVID-19 pandemic and its consequences on the planet. Remote work is very recent in Peru and, as such, it raises new challenges for public and private organizations and entities regarding the implementation of effective management strategies that guarantee, on the one hand, the productivity and optimal performance of workers, and on the other hand, their wellness and emotional health. This research also contributes to knowledge, mainly on the perception and behavior of workers when confronted with critical and unexpected situations that require the introduction of new work modalities. Finally, this research may serve as a basis for future academic studies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study follows a descriptive approach for, as Rivas (2017) points out, it “describe al sujeto de investigación, sin hacer juicios de valor sobre él pero analizando las descripciones y buscando asociaciones entre ellas[describes the research subject, without making value judgments about it while analyzing the descriptions and looking for associations between them]” (p.128). It is correlational because, according to the same author,“buscan medir el grado en que están asociadas dos o más variables[they seek to measure the degree to which two or more variables are related]” (p.132). It is cross-sectional because it focuses on obtaining data on a certain event at a certain time (Arbaiza, 2016).

The sample consisted of 148 participants of the Master’s in Administration with mention in Human Resources Management, academic period 2020, of the Postgraduate Unit of the School of Administrative Sciences of the UNMSM, Lima, Peru.

Two instruments were applied to the respondents. The first corresponded to remote work variable and included 26 items distributed in three dimensions: working hours, work and technological support, and social wellness; the second was designed to measure emotion management variable and included 20 items distributed in five dimensions: self-awareness, self-regulation, motivation, empathy and social skills. A 5-point Likert scale was used for both instruments, where 1 means “strongly disagree”; 2, “disagree”; 3, “indifferent”; 4, “agree”; and 5, “strongly agree”. Instruments were applied via Google forms, with the authorization of the Postgraduate Unit of the School of Administrative Sciences of the UNMSM.

Expert judgment was used for data validation. Results were subjected to the KMO and Barlett’s tests yielding 0.883 for remote work and 0.922 for emotion management.

Cronbach’s alpha was used in a pilot test applied to 63 students to determine the reliability of the instruments and obtained values of 0.913 for remote work and 0.950 for emotion management. Results show that the tools applied in the study have internal consistency and are, therefore, reliable.

Research professors and student members of the research team handed out the informed consent form to the respondents. In some cases, this form was provided before completing the questionnaire.

RESULTS

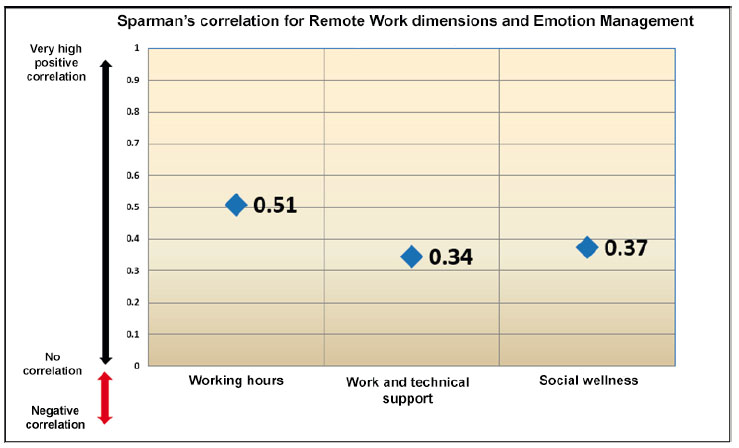

Descriptive results are shown below (see Figure 1):

Source: Prepared by the authors based on the questionnaire applied to the sample, 2021.

Figure 1 Chart showing workers’ perception on variable remote work dimensions D1, D2 and D3.

Based on the age distribution of the sample, 70% of the respondents ranged between ages 26-40, while 28% ranged between ages 41-55.

For the remote work variable, 47% of respondents were “indifferent” towards remote work, 33% “agreed” with remote work, 18% “disagreed” with remote work, and only 2% and 1% of respondents “strongly agreed” and “strongly disagreed” with it, respectively.

The distribution of dimensions D1, D2, and D3of the remote work variable is shown in Figure 1. It is observed that 41% of respondents “agreed” with working hours dimension (D1), the same percentage was “indifferent” to it, 11% “disagreed” and 6% “strongly agreed” with working hours dimension.

As for work and technological support dimension (D2), 36% of respondents declared that they “agreed” with the work and technological support received, 35% were “indifferent”, 16% indicated that they “disagreed” with it and only 12% considered that they “strongly agreed” with the work and technological support received from their organization.

Regarding the social wellness dimension (D3), 39% of respondents were “indifferent” towards it, 36% “disagreed”, 20% “strongly disagreed” and 5% “agreed” with it. These results show that 56% of all respondents stated either “disagree” or “strongly disagree” with the social wellness support provided by their organization in the context of remote work.

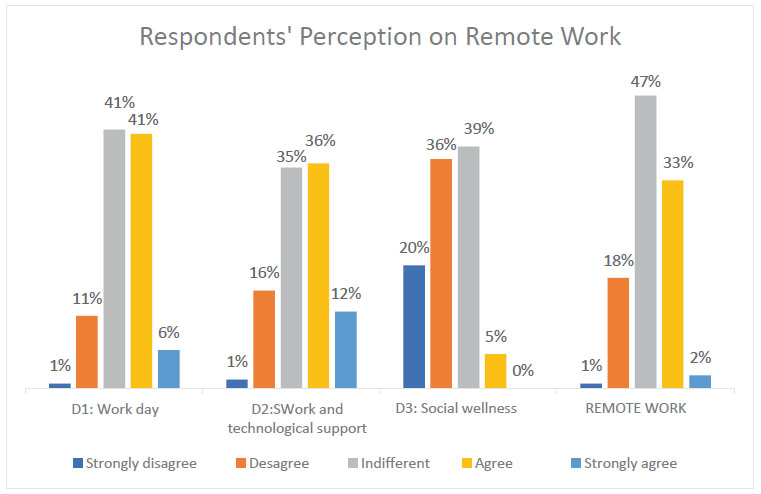

Lastly, for the variable emotion management, 61% of respondents “agreed” with emotion management, 22% “strongly agreed” with it, 14% were “indifferent” towards it, while 2% and 1% stated they “disagreed” and “strongly disagreed” with it, respectively (see Figure 2).

Source: Preparedby the authors based on the questionnaire applied to the sample, 2021.

Figure 2: Chart showing workers’ perception on variable emotion management.

Hypothesis Testing

A relationship exists between remote work and emotion management of students of Master’s in Administration with Mention in Human Resources Management, academic period 2020.

Hypothesis

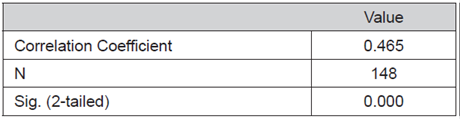

General hypothesis testing for the variables remote work and emotion management yielded the following result:

H0: r=0

There is no significant relationship between remote work and emotion management.

H1: r≠0

There is a significant relationship between remote work and emotion management.

Table 1 shows that there is a moderate positive correlation of 0.465 with a significance vel of 0.001 between remote work and emotional management in students of Master’s in Administration with Mention in Human Resources Management.

Table 1. Spearman's Rho Values for Remote Work and Emotion Management.

Source: Prepared by the authors based on results from SPSS V25 software.

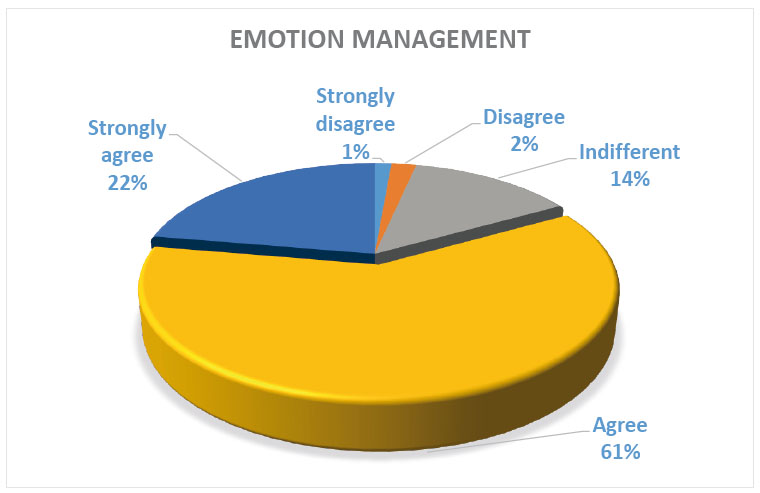

Figure 3 shows the results of the correlations of the dimensions of remote work variable (D1, D2and D3), subjected to the specific hypothesis testing, with emotional management variable. A high positive correlation of 0.51 is observed between working hours dimension (D1) and emotion management variable in students of Master’s in Administration with Mention in Human Resources Management. In addition, there is a positive correlation of 0.34 between work and technological support dimension (D2) and emotion management variable. Finally, there is a moderate positive correlation of 0.37 between social wellness dimension (D3) and emotion management variable. All three tests have a significance level of 0.01 (see Figure 3).

DISCUSSION

Research results demonstrate the existence of a positive relationship between remote work and emotion management in students of Master’s in Administration with Mention in Human Resources Management, Lima 2020, which was validated using Spearman’s Rho correlation test.

On the whole, the variables remote work and emotion management show favorable results. Although 18% of the sample “disagreed” with remote work, there were 33% who “agreed” and 47% who were “indifferent”. In other words, respondents believe that they have adapted to remote work. Likewise, 86% of respondents said they “strongly agree” or “agree” with the way they manage their emotions. These results coincide with the research by Brinca and FutureLab cited by Chávez (2021), which states that “el 49% señalan percibir emociones positivas, en tanto que el 24% afirman experiencias negativas y un 27% mantiene neutralidad, según el estudio, los resultados son bajos, ello debido a la carencia de políticas transparentes[49% of respondents experienced positive emotions, 24% reported negative experiences and 27% maintained neutrality, according to the study, results are low due to the lack of transparent policies]” [para. 1].

Regarding the first dimension of the remote work variable, most respondents reported being “indifferent” or “in agreement” with the established working hours. There is a positive and significant correlation coefficient of 0.51 between this dimension and emotion management variable. This implies that respondents accept the remote working hours and find it comfortable in general terms. These results agree with the study by Brinca and Futurelab cited by Crespo (2021), which points out that “75% de los encuestados puede trabajar remotamente los cinco días de la semana, lo cual representa una buena señal de rápida adaptación[75% of respondents can work remotely five days a week, a good sign of rapid adaptation]” (para. 10). However, there are still aspects that organizations do not consider, such as the recognition of overtime or overwork. The results of our research show that 71% of respondents reported not having received additional payment for overtime while working remotely.

Regarding labor and technological support dimension of the remote work variable, most respondents also reported being “indifferent” or “in agreement” with respect to the support they received from their organizations; that is, they perceived that their organizations did what was necessary so that the worker’s work activities would not be affected. A moderate positive correlation coefficient of 0.34 was observed between this dimension and emotion management variable. Clear labor rules must accompany work and technological support so that both the worker and the organization benefit from it, as concluded by Peralta et al. (2020) by stating that “considerando los elementos principales para la implantación de este sistema, como lo son las personas y la tecnología, aunado a la legislación, el Teletrabajo puede beneficiar tanto a las empresas como a sus trabajadores[considering the key elements for the implementation of this system, such as people and technology, together with the legislation, teleworking can benefit both companies and their workers]” (p. 334). In this sense, ITCs play a decisive role in remote work, and should be seen as an instrument that in fact does not replace the worker, but rather assists in the achievement of objectives (Buitrago, 2020).

Finally, different values were observed for social wellness dimension of the remote work variable. Most respondents “disagreed” or “strongly disagreed” with the policies aimed at the well-being of workers and their families. That is, they consider not enough attention was paid to all aspects related to this dimension by their respective organizations; therefore, the results show a positive correlation of 0.37 between this dimension and emotion management variable. In this regard, the ILO (2020) inTeleworking during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond, A Practical Guidesuggests a series of guidelines designed to enable the worker to perform remote work while minimizing the negative impact of mixing work and family spaces.

CONCLUSIONS

The research shows that remote work and emotion management are positively related. A correlation level of 0.47 is concluded, which, together with the descriptive data of both variables, suggests that respondents, on the one hand, quickly adapted to remote work and, on the other hand, successfully managed their emotions.

The correlation coefficient of 0.51 demonstrates that there is a positive and significant relationship between working hours and emotion management. Descriptive data indicate that 41% of respondents “agreed” with the remote working hours, while the same percentage was “indifferent” about it; both groups stated that there are still issues that need to be improved in their organizations.

The coefficient of 0.34 obtained indicates that there is a positive correlation between work and technological support and emotion management. Descriptive data show that 36% of respondents “agreed” and 35% were “indifferent” about remote work; only 17% “disagreed” with it. It can be deduced that most respondents have the necessary tools for the proper management of remote work.

The coefficient of 0.37 obtained indicates that there is a positive correlation between social wellness and emotions management. However, descriptive data indicate that 36% “disagreed” with the way the organization manages the social wellness of workers during remote work. It is necessary for organizations to pay attention to this dimension, given that social wellness is a non-visible aspect of this work modality.

Based on the results of this research, it is observed that, although not all aspects of remote work are addressed, the majority of the study population, made up of students of Master’s in Human Resources at Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, reported feeling comfortable working remotely and managed their emotions efficiently. Presumably the fact that most of the study participants belong to the millennial generation, who adapt quickly to technological, personal and work-related changes, explains the low level of correlation between the two variables. Nonetheless, public and private organizations need to carefully observe, redesign and better communicate those elements of the working hours, work and technological support and social wellness that were not deemed important. It is a fact that the issues encountered will be unique and different for each organization.

This research leaves open the option for new studies that include other variables such as generational gaps, gender differences, family responsibilities, among others; it serves as a basis for academic study and, above all, for organizations to make better decisions regarding this new form of employment that is probably here to stay.

REFERENCES

[1] Arbaiza, L. (2016).Cómo elaborar una tesis de grado. Lima, Perú: ESAN Ediciones [ Links ]

[2] Buitrago, D. (2020). Teletrabajo: una oportunidad en tiempos de crisis.CES Derecho, 11(1), 1-2. Recuperado de https://revistas.ces.edu.co/index.php/derecho/article/view/5620 [ Links ]

[3] Cotrufo, T., y Ureña, J. (2018).El cerebro y las emociones: Sentir, pensar, decidir. Barcelona: Emse Edapp, S.L. [ Links ]

[4] Chávez, L. (12 de febrero de 2021). Trabajo remoto: ¿Por qué los trabajadores están insatisfechos y qué se puede cambiar para el 2021?El Comercio. Recuperado de https://elcomercio.pe/economia/dia-1/trabajo-remoto-por-que-los-trabajadores-no-estan-satisfechos-y-que-se-puede-cambiar-para-el-2021-cuarentena-peru-noticia/ [ Links ]

[5] Crespo, N. (19 de febrero de 2021): El 21% de las personas trabajan remotamente de manera regular.FutureLab. Recuperado de https://futurelab.pe/el-21-de-las-personas-trabaja-remotamente-de-manera-regular/ [ Links ]

[6] D. S. No. 017-2015-TR. Decreto Supremo que aprueba el Reglamento de la Ley N° 30036, Ley que regula el teletrabajo. Diario Oficial El Peruano (2015). Recuperado de https://busquedas.elperuano.pe/download/url/decreto-supremo-que-aprueba-el-reglamento-de-la-ley-n-30036-decreto-supremo-n-009-2015-tr-1307067-3 [ Links ]

[7] D. S. No. 008-2020-SA (2020). Decreto Supremo que declara en Emergencia Sanitaria a nivel nacional por el plazo de noventa (90) días calendario y dicta medidas de prevención y control del COVID-19. Diario Oficial El Peruano (2020). Recuperado de https://busquedas.elperuano.pe/download/url/decreto-supremo-que-declara-en-emergencia-sanitaria-a-nivel-decreto-supremo-n-008-2020-sa-1863981-2 [ Links ]

[8] D. U. No. 026-2020. Decreto de Urgencia que establece diversas medidas excepcionales y temporales para prevenir la propagación del Coronavirus (COVID-19) en el territorio nacional. Diario Oficial El Peruano (2020). Recuperado dehttps://cdn.www.gob.pe/uploads/document/file/566447/DU026-20201864948-1.pdf [ Links ]

[9] D. U. Nº 127-2020. Decreto de Urgencia que establece el otorgamiento de subsidios para la recuperación del empleo formal en el sector privado y establece otras disposiciones. Diario Oficial El Peruano (2020). Recuperado de https://cdn.www.gob.pe/uploads/document/file/1473551/Decreto%20de%20Urgencia%20N%C2%B0127-2020.pdf.pdf [ Links ]

[10] Ekman, P. (2013).El Rostro de las Emociones:Qué nos revelan las expresiones faciales. Barcelona: RBA Libros. [ Links ]

[11] Estrategias y Negocio (2021).El futuro del trabajo remoto en el Perú.Estrategias y Negocios. Recuperado de https://eyng.pe/web/2021/02/11/el-futuro-del-trabajo-remoto-en-el-peru/ [ Links ]

[12] Eurofound, y Organización Internacional del Trabajo. (2019).Trabajar en cualquier momento y en cualquier lugar: consecuencias en el ámbito laboral. Oficina de Publicaciones de la Unión Europea, Luxemburgo y Oficina Internacional del Trabajo, Santiago. Recuperado dehttps://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---americas/---ro-lima/---sro-santiago/documents/publication/wcms_723962.pdf [ Links ]

[13] Gálvez, C. (2017). Inteligencia emocional. En F. Mureira (Ed.),¿Qué es la inteligencia?(págs. 63-76). España: Bubok Publishing S.L. [ Links ]

[14] Gardner, H. (2014).Estructuras de la mente: La teoría de las inteligencias múltiples. Bogotá, Colombia: Fondo de Cultura Económica. [ Links ]

[15] Goleman, D. (1996).La inteligencia Emocional. Por qué es más importante que el cociente intelectual. Buenos Aires, Argentina. [ Links ]

[16] Johnson, M., Saletti-Cuesta, L., y Tumas, N. (2020). Emociones, preocupaciones y reflexiones frente a la pandemia del COVID-19 en Argentina.Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 25, 2447-2456. Recuperado de https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232020256.1.10472020 [ Links ]

[17] Juárez, J. (2021). El futuro del Trabajo remoto en el Perú.Futurelab. Recuperado de https://futurelab.pe/el-futuro-del-trabajo-remoto-en-el-peru/ [ Links ]

[18] Ley No. 30036 (15 de mayo de 2013). Ley que regula el Teletrabajo. Diario Oficial El Peruano (2013). Recuperado de https://busquedas.elperuano.pe/normaslegales/ley-que-regula-el-teletrabajo-ley-n-30036-946195-3/ [ Links ]

[19] López, J. E. (2020). Flexibilidad, protección del empleo y seguridad social durante la pandemia global del Covid-19.Documentos de Trabajo (IELAT, Instituto Universitario de Investigación en Estudios Latinoamericanos),134 ,1-74. Recuperado de https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=7393704 [ Links ]

[20] Manucci, M. (2017). Competitividad emocional.Mercado. Recuperado de https://mercado.com.ar/management-marketing/competitividad-emocional/ [ Links ]

[21] Ministerio de Justicia y Derechos Humanos y SERVIR (2016).Guía sobre el sistema administrativo de Gestión de Recursos Humanos en el Sector Público.Guía para asesores jurídicos del Estado. Recuperado dehttps://www.minjus.gob.pe/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/MINJUS-DGDOJ-Gu%C3%ADa-sobre-el-Sistema-Administrativo-Servir.pdf [ Links ]

[22] Ministerio de Trabajo y Promoción del Empleo (2019) Manual de preguntas frecuentes laborales. Recuperado de https://cdn.www.gob.pe/uploads/document/file/307150/MANUAL_DE_PREGUNTAS_FRECUENTES.pdf [ Links ]

[23] Organización Internacional del trabajo OIT (1966).C177 - Convenio sobre el trabajo a domicilio, 1996 (núm. 177). Recuperado de https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/es/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:C177 [ Links ]

[24] Organización Internacional del Trabajo OIT (2020).El teletrabajo durante la pandemia de COVID-19 y después de ella. Guía práctica .Recuperado dehttps://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---protrav/---travail/documents/publication/wcms_758007.pdf [ Links ]

[25] Organización Mundial de la Salud (2020).COVID-19: Cronología de la actuación de la OMS. Recuperado de https://www.who.int/es/news/item/27-04-2020-who-timeline---covid-19 [ Links ]

[26] Peralta, A., Bilous, A., Flores, C., y Bombón, C. (2020). El impacto del teletrabajo y la administración de empresas.Recimundo, 4(1), 326-335. Recuperado de https://doi.org/10.26820/recimundo/4.(1).enero.2020.326-335 [ Links ]

[27] Rivas, L. A. (2017).Elaboración de Tesis. Estructura y Metodología. Ciudad de México, México: Editorial Trillas. [ Links ]

[28] Salovey, P, y Mayer, J. D. (1990). Emotional Intelligence.Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 9(3), 185-211. Recuperado de https://doi.org/10.2190/DUGG-P24E-52WK-6CDG [ Links ]

[29] Weller, J. (2020).La pandemia del COVID-19 y su efecto en las tendencias de los mercados laborales. Santiago, Chile: CEPAL. Recuperado de https://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/45759/1/S2000387_es.pdf [ Links ]

[15] Countries observed are: Argentina, Brazil, India, Japan, the United States, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Netherlands, Spain, Sweden and Great Britain

Received: March 15, 2021; Accepted: April 24, 2021

text in

text in