Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Industrial Data

versión impresa ISSN 1560-9146versión On-line ISSN 1810-9993

Ind. data vol.24 no.2 Lima jul./dic. 2021 Epub 31-Dic-2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.15381/idata.v24i2.20435

Production and Management

Commitment-based Management in the Spare Parts Warehouse Area of a Car Dealership in Lima

2 Industrial Engineer from UNMSM (Lima, Perú). Currently working as Specialist in Logistics Control in Banco Central de Reserva del Perú (Lima, Peru). E-mail: cristiansegovia@outlook.com

The automotive sector is a large player in the Peruvian economy; however, it has been affected in recent years by the political situation, changes in the tax code and high competitiveness in the sector, which has mainly affected commercial results. In this situation, the need to develop a management tool that helps lead teams in this sector and that is applied to the Peruvian reality becomes important. This study focused on the spare parts warehouse team belonging to the after-sales management of a car dealership in Lima. Likewise, the study shows the implementation of Commitment-based Management as a management and direction tool to improve the gross margin obtained by the sub-management in charge, by verifying its effectiveness in the results of the period analyzed.

Keywords: management; commitments; warehouse; spare parts; automotive.

INTRODUCTION

The automotive sector in Peru is mainly comprised of the sale of vehicles, box vans, fuel, supplies, and the offer of automotive services. Negri (2019) states that the automotive sector generates 12% of the national GDP by producing more than S/ 15 000 000 000, which is equivalent to 14% of tax revenues in Peru. In this regard, INEI (2020) informs that retail trade grew 3.14% boosted by the sale of fuels and lubricants for automotive vehicles. It also mentions that the motor trade grew 4.62% due to increased sales of light-duty and heavy-duty vehicles, which resulted in an increased demand of auto parts, accessories, wheels, and other items. However, preventive and corrective maintenance services showed a decline in the same period.

The Asociación Automotriz del Perú (2019) points out that the fleet of motor vehicles in Peru, according to the general manager Ellioth Tarazona, has a motorization rate of 10.7 -whereas in Chile, Argentina, and Mexico there are between 3 and 3.3 people per vehicle-, with an average age of 13.6 years per vehicle, which results in higher fuel consumption, pollution, cost overruns, and other issues. In addition, there has been a drop in vehicle importation since 2014 due to the increase of the Selective Consumption Tax (Impuesto Selectivo al Consumo - ISC) for vehicles. It must be noted that the tax on the acquisition of vehicles was increased between 20% to 40% according to the Decreto Supremo N.° 095-2018-EF (2018); later, the ISC was modified again through the Decreto Supremo N.° 181-2019-EF (2019), in which the tax was reduced for vehicles with certain engine displacements and was raised for the purchase and sale of second-hand vehicles.

One of the areas of the automotive sector that generates a high percentage of revenues is spare parts, as spare parts are necessary to maintain the value of the goods. The Asociación Automotriz del Perú (2020) states that importation of supplies dropped 2.6% during 2018 and 2019, which, together with the rise in prices and the high competitiveness, had a detrimental effect on the sector as it faces customers seeking better prices, thus directly affecting profitability. Accordingly, there is a potential decrease in the automotive sector as well as difficulties due to tax and competition issues, so it is necessary to develop a management tool that supports the interdisciplinary teams in this sector and that is adapted to the situation in Peru.

The spare parts area is comprised by the sales, purchasing and warehouse sub-areas; the latter are responsible for receiving the merchandise, storage, delivery, coding and attending to workshop orders. Therefore, this work was focused on the warehouse area as the teams of warehousemen, made up of assistants and managers, are responsible for identifying the supplies and spare parts required by the workshop for the repair or maintenance of the vehicles to be worked on, without neglecting their own warehouse tasks, so they need a simple management system that manages to boost their activities and does not reduce the time focused on their core business.

This study makes use of the Commitment-based Management tool, which helps boost team productivity. This tool has been developed and adapted to the Peruvian reality of small car dealerships and seeks to support, initially, the spare parts warehouse area due to its particular casuistry as it requires a warehouse equipment management tool that allows channeling its daily activities in order to fulfill the objectives of the after-sales management. Likewise, the most influential factor in the short term is the gross margin of the area, as Peruvian car dealerships mainly focus on sales; for this reason, it was chosen to be the central axis of the project results in this study.

It should be noted that this management tool has been adapted to the reality of small car dealerships in the city of Lima, based on the experiences obtained in the implementation of Commitment-based Management in Divemotor, the group representing Mercedes Benz in Peru. This tool is focused on after-sales management, so it is of a novel nature that does not exclude other existing methodologies. Likewise, this methodology can be extended to other after-sales areas of car dealerships, such as workshop, spare parts planning, spare parts sales, among others, which gives room for future research about its implementation in commercial areas and in other companies belonging to the automotive sector.

According to Gestión (2015), the Deloitte report Tendencias Globales de Capital Humano 2015: Liderando en el nuevo mundo del trabajo shows that 87% of human resources and business leaders worldwide consider the lack of engagement as the main concern of companies. The biggest gap in Peru would be “culture and engagement”.

On the other hand, Repsol (2013) is an oil and gas sector company focused on 3 key regions: North America, Latin America, and Southeast Asia. The company seeks to train its personnel and provide them with opportunities for development through performance review, where they analyze their potential and work on their areas of improvement. It also has two management tools for employee recognition: Commitment-based Management, where they seek cohesion between objectives for operational personnel, and Results-based Management, for administrative personnel.

In this regard, Ramos and Albitres (2010) point out that the Peru is still in its infancy regarding the implementation of Results-based Management, mainly in efficiency and quality of public spending. They also identify deficiencies in training, planning, programming, and management capacity to the detriment of qualitative and quantitative objectives.

Divemotor (2017), official distributor in Peru of Mercedes-Benz, Jeep, Dodge, Ram, and Freightliner, is comprised of the companies Diveimport and Divecenter. In 2016, the company implemented Commitment-based Management (CbM) as a tool to direct the efforts of the commercial and logistics areas towards improving the profitability of the company within a period of recession in mining and construction investments. This resulted in a 42% increase in market penetration in the prospective client segment, which increased the average monthly sales based on client development. It also implemented a coding center, which reduced waiting times for quotations for the workshop channel, increasing workshop availability and, therefore, the average daily workshop service. In addition, it increased the “service level” indicator of the warehouse because of the faster service of workshop orders and reduced in manufacturing reworks.

In summary, these results had a direct impact on the profitability increase of the company due to the raise in the average sales per workshop or per counter, originated by a higher average monthly sales per customer and a greater number of sales per day as a result of the reduction in service times. It should be noted that profitability depends on factors such as overhead costs and expenses; gross margin, on the other hand, is the factor affected by direct sales.

The framework outlined above concludes with the statement of the main problem: Is the implementation of Commitment-based Management in the spare parts warehouse area necessary to improve the gross margin in a car dealership?

The objective of this research is to determine the improvement of the gross margin in the spare parts warehouse area of a car dealership after the implementation of Commitment-based management.

HYPOTHESIS

In response to the main problem, the hypothesis proposed is “The implementation of Commitment-based Management in the spare parts warehouse area improves the results of the gross margin in the spare parts sub-management in a car dealership”.

Dependent variable:

Y1: Gross margin of the spare parts sub-management with respect to total sales

Independent variable:

X1: Compliance level of Commitment-based Management in the spare parts warehouse area

According to Real Academia Española (2020), “commitment” is defined as an obligation undertaken, a word given, a difficulty, a promise. However, Sull (2003) -an expert in strategy and execution, professor of strategy and entrepreneurship at Harvard and London Business School and one of the 10 new management gurus- points out that a commitment is an action taken in the present that binds an organization to a future course of action. In other words, not all management decisions are commitments, since such decisions become a commitment if it constrains future alternatives a company in a way that would be difficult to reverse. He also argues that, in the medium term, commitments facilitate the resolution of problems within operations and organizations, and that they provide employees with a sense of focus, as well as helping to prioritize and coordinate actions.

On the other hand, Dougherty (2012) -a senior lecturer in technological innovation, entrepreneurship, and strategic management at MIT with experience in stabilizing and recapitalizing companies- argues that for a leader to achieve emotional engagement with their team, it is necessary to engage with them as well, unsolicited and without an expectation of reciprocity. He also states that commitments cannot be forced or faked, because this leads to mistakes and rejection, so cohesion is sought with the people with whom one works. On the other hand, he points out that commitments generate inflexibility if they are proposed for long periods, so if there are changes in time, the company may be trapped in outdated objectives to the detriment of adaptability, operability, and competitiveness.

Commitment-based Management (CbM)

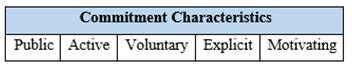

Dann (2009) argues that, according to Donald Sull, hierarchies are systems where orders go down and information goes up, so they are not appropriate for jobs where cooperation between multiple teams with different functions is sought. Traditionally, this casuistry was managed through processes, standardizations and decision making derived from the Total Quality Management (TQM) approach, which resulted in a high level of process standardization, but led to a lower level of innovation. In response, Sull developed the concept of Commitment-based Management, where he schematizes an organization as a network of overlapping commitments that motivate workers to work in the right way. One advantage of this concept is that it can be used in non-standard situations, such as emerging strategies, innovation, crisis, chaos, etc.; it also encompasses the entire supply chain. In this regard, it identifies five characteristics, which are shown in Table 1.

In addition, Sull and Spinosa (2005) state that this approach does not exclude others but should be treated as a complement to achieve better results, such as guiding personnel to achieve objectives and optimizing production processes.

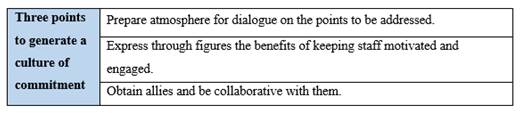

Goldsmith (2008) points out that leaders must inspire respect and trust in order to increase commitment in a company, so that employees feel linked to the results of the organization. This technique includes open and effective communication, transparency, truth, equality, coaching, empowerment, and recognition of achievements. Table 2 outlines the recommendations for top management support.

Generation variables

Stein and Pin (2009) argue that there is currently an integration between the different generations that coexist in the same workspace. This boosts the need to understand the expectations, values, needs and motivations of the latest generation incorporated. The management of this situation could lead companies to their eventual development or stagnation.

Millennials opt for companies that offer a balance between their personal life and work, where they have access to information, empowerment, fluid communication with department leaders, challenges and opportunities for learning and development. In return, they will offer a high level of preparation, creativity, initiative, among other characteristics that will help to achieve the results desired by the companies.

Motivation and Leadership

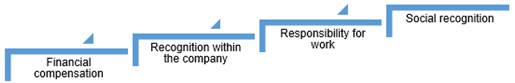

Newstrom (2011) argues that motivation at work is comprised of internal and external forces that direct an employee to choose a course of action and act in certain ways and that, from an ideal point of view, these behaviors will be directed to the achievement of an organizational goal.

Accordingly, the personality and needs of the employees are the main axes that managers must evaluate to ensure their employees are motivated. Figure 1 shows the main sources of motivation according to Newstrom:

On the other hand, Viato (2014) refers that leadership consists of a method intended to guiar, acompañar y entrenar a una persona o un grupo con el propósito de alcanzar metas o desarrollar habilidades específicas [guide, accompany and train a person or a group of people with the purpose of achieving goals or developing specific skills] (para. 2). In this process, the leader intervenes as a coach for his follower to improve the performance of their functions by focusing on the achievement of objectives.

METHODOLOGY

This study is quantitative based on an experimental design. The type is applied, and the level is explanatory and descriptive.

The study population is made up of 63 car dealerships that operate in Lima and are engaged in the sale of light-duty vehicles, after-sales services, and the commercialization of spare parts. The company Limautos Automotriz del Perú S.A.C. was defined as the sample, which is non-probabilistic, as it is a company that meets the required characteristics and it was feasible to carry out the research at its facilities.

The stages developed are as follows:

Implementation of Commitment-based Management

Identify deficiencies in the area and group them into improvement axes or factors according to common criteria.

Train warehouse personnel and their managers in Commitment-based Management.

Define the frequency and time intervals to be used for commitment monitoring meetings.

Design the CbM rating chart for the quantification of factor compliance. This table rates with zero or one each factor fulfilled for each branch analyzed.

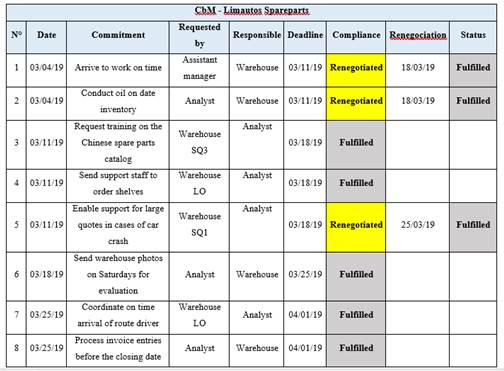

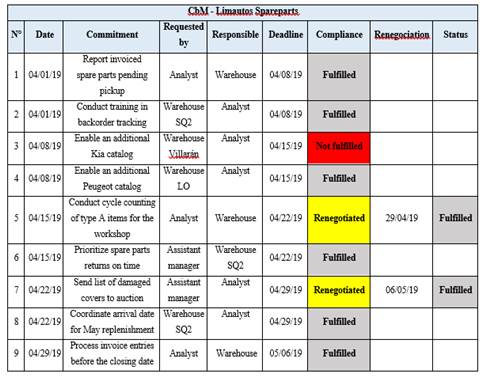

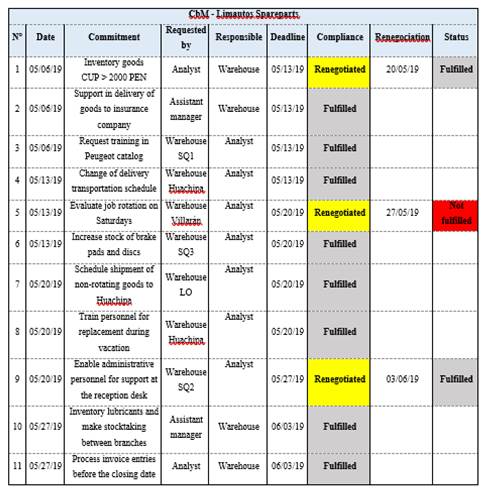

Start the commitment meetings according to the parameters set, in which, on a weekly basis, an applicant establishes different commitments and proposes a date of compliance and a responsible for execution. The week after each meeting, compliance will be reviewed and record will be kept of whether the request has been complied with, a new date has been agreed on or the request has not been fulfilled.

Evaluation of Results

Generate a month-end summary of the implementation effects on the performance of the warehouse personnel with respect to the factors identified at the beginning of the project.

Evaluate the aforementioned factors in each branch and record them in the CbM rating chart to quantify factor compliance.

Calculate the monthly rating of the area considering the average obtained from the factors from each branch.

Design a summary chart with the monthly compliance of the area.

Create a chart containing the monthly gross margin of the area.

Perform a correlation assessment between the Commitment-based Management and the gross margin performance of the area during the project execution.

Based on the results obtained, continue with the Commitment-based Management and make the identifiable adjustments.

To obtain the results of the dependent variable, the monthly report to the board of directors was reviewed, where the results of sales, gross margin by area, inventory, warehouse satisfaction, profitability, among others, are detailed. The results of the independent variable were obtained from the summary chart of the monthly fulfillment with the Commitment-based Management. Finally, based on the project results in the term coordinated with management, the degree of correlation between the independent variable and the dependent variable was determined, from which it can be affirmed that the Commitment-based Management project improved the productivity of the warehouse personnel, which was reflected in the increase of the gross margin of the spare parts sub-management, resulting in the validation of the hypothesis proposed.

RESULTS

Implementation of Commitment-Based Management

Limautos Automotriz del Perú S.A.C. is a company established in 2011 that sells spare parts for the KIA, Mitsubishi, FUSO, Peugeot, MG, and Chery brands. It has ten branches in Lima, six of which offer spare parts service in workshops and four of which have counter sales points. Its vision is Ser líder de la industria, manteniendo la capacidad de diferenciación en el mercado e impactando responsable y socialmente en el entorno [Be the industry leader, maintaining the capacity for differentiation in the market and have a responsible and social impact on the environment] (Limautos Automotriz del Perú S.A.C., n.d.). This company has never had a process and quality area, so the mapping of internal processes is managed by each management, which means that the spare parts sub-management, which includes the spare parts warehouse area, does not have a plan or methodology to manage its results and focuses on solving daily problems, overshadowing planning and equipment management.

Based on the deficiencies identified in the aforementioned company, the implementation of CbM was proposed as a management tool for the warehouses of the spare parts sub-management in order to improve its gross margin. The following three axes of the project were identified and their management was planned to increase the gross margin of the spare parts sub-management:

The warehouse area does not generate sales directly; however, it codes the spare parts required by workshops and attends the spare parts requested by counter and workshop, which would be typified as indirect sales.

The warehouse area manages the stock of spare parts that may generate expenses for inventory adjustments and expenses due to obsolescence.

The warehouse area processes invoices for purchased spare parts, which, if entered incorrectly, can generate accounting expenses and inventory errors.

In order to introduce the Commitment-based Management (CbM) implementation project to the warehouse team, a training day was held for the spare parts sub-management personnel on December 27, 2018. In this training, it was explained what commitments are, their status (“Fulfilled”, “Pending”, “Not Fulfilled” and “Renegotiated”), their implications, the ease of making requests to management and vice versa, so that they commit to actions that facilitate day-to-day functions, the priority of teamwork, among other topics. In addition, three group-dynamic games were applied: Win-win, Spaghetti Tower, and Square Jump, which helped the sub-management personnel to get to know each other better and develop bonds of friendship. Finally, the day ended with a soccer tournament.

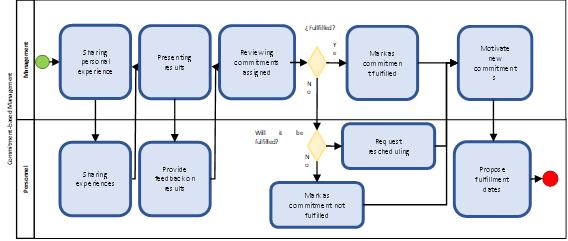

Based on the Commitment-based Management implemented at Divemotor in 2016, meetings of 20 to 25 minutes were scheduled on Mondays at 8:00 a.m. to review commitments and their fulfillment. It should be noted that punctuality was the first commitment to be developed among workers. Figure 2 shows the actions to be carried out during the commitment meetings.

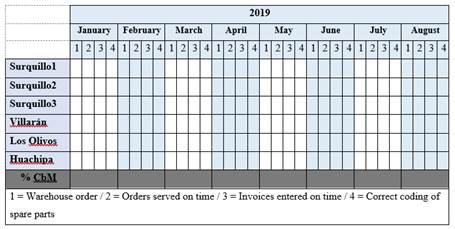

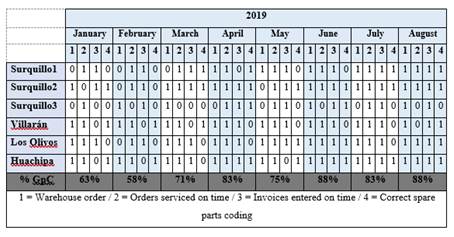

The methodology selected requires a CbM rating chart to quantify compliance with the factors, so the same scheme used at Divemotor was used. However, due to the warehouse characteristics and its lack of time availability as a consequence of the backlog generated as a result of the interval between the opening of the workshop at 7:00 a.m. and the opening of the warehouse at 8:00 a.m., the processes were simplified in order to have the meetings at 7:00 a.m. and 8:00 a.m., respectively, and Table 3 was designed for the warehouseman, the warehouse analyst and the spare parts manager.

The above table shows a result per branch, which is subdivided into four factors: warehouse order, orders served on time, invoices entered on time and correct coding of parts. The criteria used for the monthly evaluation are detailed below:

Warehouse order: The warehouses must be in order, with the items coded and located on the corresponding shelves according to the system. All items delivered must be invoiced in the ERP system or identified for prompt invoicing. Compliance with this factor results in a reduction in expenses for inventory adjustment.

Orders complete on time: Pickings for counter and shop customers must be handled in a timely manner with no errors in quantities or coding. Compliance with this factor reduces the expenses for inventory adjustments and the delay in attending to workshop customers, thus increasing their availability, which results in a greater flow of customers.

Invoices entered on time: There is a deadline of 24 hours to receive invoices and an additional 24 hours to send them to the main branch. Compliance with this factor reduces administrative task times and offers a greater possibility of detecting nonconforming items within 24 hours for filing claims.

Correct coding of spare parts: The workshops request daily coding, which must be done in the shortest possible time according to difficulty, stock availability, replacement codes and price requests to the importer. Compliance with this factor reduces obsolescence costs and results in a lower number of reprocesses.

Table 3 was planned to be filled out in a monthly meeting between the warehouse analyst and the spare parts coordinator. They were given a value for each criterion of one (1) if it was met or zero (0) if the warehouse performance was not as required.

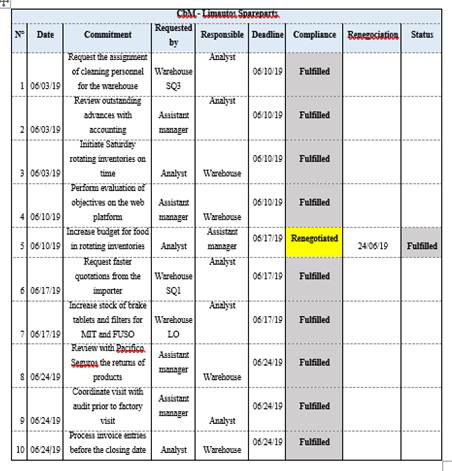

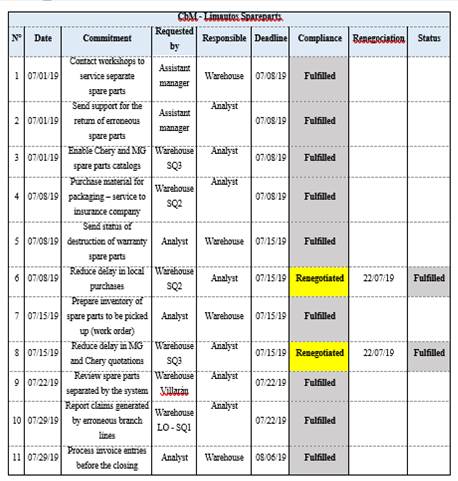

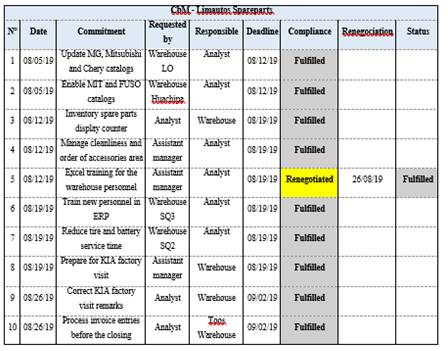

The project started in full the first week of March 2019. Each Monday meeting was led by the warehouse analyst, who proposed the commitments per each branch in order to improve their operational issues, and storekeepers were empowered so they could also engage the analyst and the assistant manager in actions that would help the area perform better. The commitments proposed throughout the project are detailed in Table 4, Table 5, Table 6, Table 7, Table 8, and Table 9.

EVALUATION OF RESULTS

Based on the commitments managed weekly, the following results were obtained at warehouse management level:

March: The personnel had a positive change in their arrival schedule due to the commitment promoted by the sub-management. Deficiencies in oil inventories were corrected, problems due to lack of training were identified in catalogs, and support was provided to branches that had a high operational load due to the entry of damaged vehicles. Operational problems were identified in Surquillo3 due to the lack of experience of the assigned personnel, for which Surquillo2 initially provided support. Regarding invoice entry, two branches finished out of working hours; therefore, it was considered as “not fulfilled” in the commitment chart.

April: Training was provided on tracking charts to reduce expenses due to obsolescence, additional catalogs were obtained to increase productivity in workshop coding, and inventories of high turnover items were taken to reduce incidences of stock shortages and surpluses. In this month most of the invoices were entered within working hours, which was acknowledged by different managers. There were still errors in coding at branches with new personnel.

May: The delivery of merchandise for the counter was expedited and there was greater availability in the warehouse, training was provided for catalog updates, the stock level of some spare parts groups was increased, and the recurrence of lubricant inventories was increased in order to identify causes of oil shortages. With respect to the tracking charts, there was a setback in compliance due to problems with the coding of claims and observations in the warehouse order due to the arrival of replacement parts for 1.5 months of stock.

June: The personnel had another change related to the punctuality of Saturday inventories, which caused them to be completed on schedule; also, outstanding advances pending of invoicing were identified in order to reduce obsolescence and requests were made to the importer to reduce waiting times (between 1 and 3 days) for quotations of imports. On the other hand, new parameters were negotiated for filter replacements due to the high variability in the last month. In general, the best results in the Commitment-based Management were obtained as there was a reduction of incidents.

July: In order to reduce obsolescence, pending tasks were tracked in the workshop. From another point of view, new catalogs for Chinese spare parts were made available and planning for the destruction of warranty spare parts was started. The importer was asked again to reduce the response time for quotations of imported Chinese spare parts, and steps were taken to return to the factory from the branches with coding errors due to the responsibility of the importer. In addition, there were difficulties in Surquillo3 due to the departure of assigned personnel on vacation and there were errors in the coding of low turnover electrical items.

August: Three catalogs with errors were updated and the personnel retrained in the Huachipa plant. Prior to the factory visit, each warehouse was inspected and order and cleanliness issues were corrected. As part of the annual objectives, training was provided in Excel and SPIGA+ to expedite internal warehouse processes. Coordinated with the purchasing department to expedite quotes for local items. By this time, several locations had already achieved 100% compliance with the CbM, so the analyst was asked to prioritize the two locations that still have problems.

In general, the team achieved punctuality, on-time compliance of rotating inventories and invoice entry. In addition, priority was given to training and catalog updates, and support was provided to the different branches in overloaded workdays and when replacement personnel were needed for vacations. Finally, the closing of invoice receipts on time was completed, actions that were acknowledged by the Administration Management.

It should be noted that during January and February, the scheme was proposed without actually involving Commitment-based Management, which was considered to be fully initiated as of March 2019.

As explained above, each branch was evaluated in a monthly meeting between the warehouse analyst and the spare parts coordinator, which generated the results shown in Table 10.

Growth was observed in the Commitment-based Management compliance indicator, which started with 63% when the project was not fully implemented and had a value of 88% by August: a result of the cohesion in the warehouse team.

Contrast de hypotheses: CbM vs. Gross Margin

Based on Table 8, Table 11 was developed as a summary, where the percentage of CbM compliance during the project was identified:

Table 11 Summary of the CbM Compliance Chart.

| Month | CbM |

|---|---|

| MAR | 71% |

| APR | 83% |

| MAY | 75% |

| JUN | 75% |

| JUL | 83% |

| AUG | 88% |

Source: Prepared by the author.

On the other hand, Table 12 shows the gross margin percentage of the spare parts area from March to August 2019.

Table 12 Monthly Result of Gross Margin.

| Gross Margin | MAR | APR | MAY | JUN | JUL | AUG | YTD |

| General | 33% | 30% | 28% | 27% | 32% | 30% | 30% |

| Canal Mostrador | 25% | 27% | 19% | 25% | 23% | 29% | 23% |

| Canal Taller | 37% | 32% | 31% | 30% | 36% | 33% | 33% |

Source: Prepared by the author.

It should be noted that since the performance of the workshop channel was under the leadership of the workshop assistant manager, it was decided to use only the value of the counter channel. Also, based on the details of the hypothesis, Table 13 was generated, in which the values for the variables were identified.

Table 13 Identification of Dependent and Independent Variables.

| Month | Y: Gross Margin | X: CbM |

|---|---|---|

| MAR | 25% | 71% |

| APR | 27% | 83% |

| MAY | 19% | 75% |

| JUN | 25% | 75% |

| JUL | 23% | 83% |

| AUG | 29% | 88% |

Source: Prepared by the author.

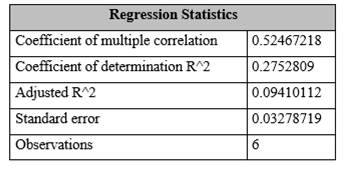

Finally, Table 14 was generated, where the correlation coefficient was determined using Excel 2019, Data tab, Analysis section, Data Analysis tool, Regression option.

When reviewing the statistical results, it is observed that the correlation coefficient is 0.52, which indicates that there is a positive correlation between the dependent and independent variables, so the hypothesis stated is considered valid. However, when analyzing the coefficient of determination R2, a value of 0.275 is observed, which means that the model slightly explains the variability of the response data as a function of its mean, so the data may be far from the regression graph.

Also, it is detailed in the analysis provided by Excel 2019, where the regression equation is as follows:

Y = 0.025 + 0.28 X

This equation indicates that there is a positive slope, which reinforces the affirmation of the positive correlation between the variable “compliance level of Commitment-based Management in the spare parts warehouse area” and the variable “gross margin of the spare parts sub-management with respect to total sales”.

DISCUSSION

With respect to the previous point, it is confirmed that the higher the compliance with Commitment-based Management, the higher the gross margin of the spare parts management, according to the success cases previously presented in the implementation of Commitment-based Management in the companies Repsol and Divemotor. Divemotor, which belongs to the same business sector, managed to increase the average monthly workshop and counter sales while increasing its gross margin; just like the company analyzed in this study.

On the other hand, when reviewing the CbM compliance chart, there is an increase in compliance with CbM since March, the date on which the CbM training for the area in question was validated. In addition, there is a drop in compliance during some months, which suggests the presence of internal factors that generated a delay in the project during some months.

Likewise, after the analysis, a pattern for the development of CbM among collaborators and managers was observed, which leaves room to evaluate the application of this tool in other organizations with a position structure similar to the one proposed in this study and with operational personnel with high school or technical studies, for which the following steps are recommended:

Identify the critical factors that require monitoring.

Request authorization from the corresponding management, supporting the necessity of the project for an improvement in gross margin.

Start the initial CbM training meeting to develop bonds among collaborators. Also, prioritize the win-win mentality as the initial axis of the commitments.

Generate a commitment chart with the indicators of the identified factors.

Appoint personnel for monitoring and elaborate a meeting schedule.

Initiate meetings according to the proposed methodology. In the meetings, the majority of the team should participate in order to increase the confidence of the personnel. Commitments must be achievable and must be developed with responsibility on both sides.

After the first six months of the project, carry out the first evaluation of the gross margin to recognize the results and make the necessary adjustments to provide continuity to the project.

Additionally, it is proposed to start in an End-to-End area to reduce the presence of external factors that may complicate the fulfillment of commitments. Likewise, it is proposed to extrapolate this tool to other companies that have a structure focused on sales and do not have a process and quality area, such as lubrication stations, mechanical workshops, spare parts distributors, accessory dealers, among other companies in the automotive industry.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

This study concludes that there is a positive correlation between the level of compliance with Commitment-based Management and the gross margin of the spare parts sub-management focused on the counter, which is supported by the growth of the margin during the execution of the proposed project.

Commitment-based Management serves as a tool to facilitate teamwork, to align efforts in search of common objectives, to provide empowerment to operating personnel and to collaborate with the development of the new generations that are entering into the labor market and have different motivations and goals.

It is recommended that the model presented is applied over a longer period of time to obtain more information and numerical data that will allow a complete analysis of the variability of the data with respect to the regression indicated. Likewise, the methodology presented should be applied to the workshop sub-management to obtain a complete picture of the influence of Commitment-based Management in the spare parts sub-management of the company in study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos

Limautos spare parts sub-management

REFERENCES

Asociación Automotriz del Perú. (2019). AAP: los efectos de un parque automotor escaso y antiguo. Recuperado de https://aap.org.pe/aap-los-efectos-de-un-parque-automotor-escaso-y-antiguo-2/ [ Links ]

Asociación Automotriz del Perú. (2020). Importación de suministros 2018. Recuperado de https://aap.org.pe/estadisticas/importacion_suministros/importacion-de-suministros-2019/ [ Links ]

Dann, J. (2009). Manage by commitments, not hierarchies by Donald Sull. CBS NEWS. Recuperado de https://www.cbsnews.com/news/donald-sull-manage-by-commitments-not-hierarchies/ [ Links ]

D. S. N.° 095-2018-EF. Modifican el Literal A del Nuevo Apéndice IV del Texto Único Ordenado de la Ley del Impuesto General a las Ventas e Impuesto Selectivo al Consumo. Diario Oficial El Peruano (miércoles 9 de mayo de 2018). [ Links ]

D. S. N.° 181-2019-EF. Decreto Supremo que modifica el Impuesto Selectivo al Consumo aplicable a los bienes del Nuevo Apéndice IV del TUO de la Ley del Impuesto General a las Ventas e Impuesto Selectivo al Consumo y el Reglamento de la Ley del Impuesto a la Renta. Diario Oficial El Peruano (sábado 15 de junio de 2019). [ Links ]

Divemotor. (2017). La Empresa. Recuperado de https://www.divemotor.com/empresa/ [ Links ]

Dougherty, J. (2012). To get a commitment, make a commitment. Harvard Business Review. Recuperado de https://hbr.org/2012/12/to-get-a-commitment-make-a-com [ Links ]

Gestión. (2015). El 87% de empresas considera que la falta de compromiso laboral es su principal problema. Recuperado de https://gestion.pe/tendencias/management-empleo/87-empresas-considera-falta-compromiso-laboral-principal-problema-105592-noticia/?ref=gesr [ Links ]

Goldsmith, M. (2008). How to increase Employee Commitment. Recuperado de https://hbr.org/2008/01/how-to-increase-employee-commi [ Links ]

INEI. (2020). Actividad comercial aumentó 3,47% en noviembre de 2019. Indicadores Económicos, Boletín Estadístico 02. Recuperado de https://www.inei.gob.pe/media/MenuRecursivo/boletines/boletin-quincenal-02_2.pdf [ Links ]

Limautos Automotriz del Perú S.A.C. (s.f.). Misión. Recuperado de https://www.limautos.pe/nosotros [ Links ]

Negri, A. (2019). 2020: Una meta en común. Asociación Automotriz del Perú, Boletín 125. [ Links ]

Newstrom, J.W. (2011). Comportamiento humano en el trabajo. México D.F., México: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Ramos, L., y Albitres, R. (2010). Sistema de gestión para resultados en el Perú. Tesis de maestría. Universidad Nacional de Ingeniería, Lima. [ Links ]

Real Academia Española (s.f.). Compromiso. En Diccionario de la lengua española. Recuperado de http://dle.rae.es/srv/search?m=30&w=compromiso [ Links ]

Repsol. (2013). Informes 2013. Equipo Repsol. Retención del Talento. [ Links ]

Sull, D. (2003). Managing by commitments. Harvard Business Review. Recuperado de https://hbr.org/2003/06/managing-by-commitments [ Links ]

Sull, D.N., y Spinosa, C. (2005). Using commitments to manage across units. MIT Sloan Management Review, 47 (1), 73-81. Recuperado de https://www.researchgate.net/publication/40968864 [ Links ]

Stein, G., y Pin, J.R. (2009). Como dirigir a las nuevas generaciones de profesionales: motivaciones y valores de la generación Y. Harvard Deusto Business Review, (178). Recuperado de https://www.harvard-deusto.com/como-dirigir-a-las-nuevas-generaciones-de-profesionales-motivaciones-y-valores-de-la-generacion-y [ Links ]

Viato, R. (12 de enero de 2014). Poderosa herramienta. Revista D. Recuperado de https://www.prensalibre.com/revista-d/coaching-liderazgo-recursos-humanos-gestion-de-tiempo-desarrollo-profesional-0-1062493984/ [ Links ]

Received: May 25, 2021; Accepted: August 23, 2021

texto en

texto en