Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Industrial Data

Print version ISSN 1560-9146On-line version ISSN 1810-9993

Ind. data vol.25 no.1 Lima Jan./Jun. 2022 Epub July 31, 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.15381/idata.v25i1.21990

Production and Management

High Performance Leadership and its Relationship with the Organizational Climate in a Peruvian Company in the Industrial Sector in Lima, 2021

1Psychologist. Currently working as assistant manager of People and Sustainability at Calaminon (Lima, Peru). E-mail: jpereyra@calaminon.com

2Master’s in Business Management from Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos. Currently working as researcher and administrative personnel at Universidad de Lima (Lima, Peru). E-mail: dreyc@ulima.edu.pe

3PhD degree in Administration and Education. Currently working as professor at the Postgraduate Unit at the School of Economic Engineering, Statistics, and Social Sciences of Universidad Nacional de Ingeniería (Lima, Peru). E-mail: juribek@uni.edu.pe

The main objective of this study was to determine the level of relationship between high performance leadership and organizational climate in a population of 280 workers of a Peruvian company in the industrial sector dedicated to modular construction. A total of 108 people who exercised some type of leadership according to the nature of their position was identified. The study was applied to the entire group by means of an analysis with Likert-type surveys. According to the results, the variable “high performance leadership” and “organizational climate” are significantly and positively correlated (0.812). The dimensions of the variable “high performance leadership” are “personal leadership”, “relational leadership” and “organizational-strategic leadership”. In the case of the dependent variable “organizational climate”, the dimensions are “personal factors”, “relational-group factors” and “organizational factors”. It is concluded that high performance leadership and all its dimensions are related to organizational climate.

Keywords: high performance leadership; personal leadership; relational leadership; organizational-strategic leadership; organizational climate

INTRODUCTION

Leadership, as such, is presented as a necessary characteristic for the survival and development of humanity. In fact, the first civilizations, such as Sumer, left evidence of leadership at an organizational level (Estrada, 2007) that was essential for their development at that social level. However, its formal study began in the first decades of the twentieth century, approached from different disciplines such as sociology, psychology, and management. This resulted in different approaches and methodologies that in many cases were affected by their opposing results (Yukl, 1990).

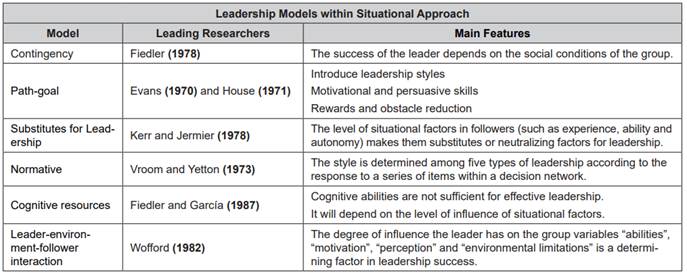

In this context, theories that are generally classified by perspective or approach stood out. The trait theory, based on the research of Taylor (1911), Mayo (1933), and Maslow (1943), identifies characteristics inherent to the leader, such as an above average level of intelligence, and high levels of energy and persuasiveness (Bass, 1990; Kirpatrick & Locke, 1991). In contrast to this theory, the behavioral theory approach, in which the research of Shartle (1956) and Stogdill (1963) stands out, studies the behavior of a leader. Thus, it relates effective leadership behavior to the category “initiating structure”, referring to the elements necessary to accomplish a task, and the category “consideration”, composed of those behaviors aimed at achieving positive interrelationships (Misumi & Peterson, 1985). Finally, the situational approach, derived from the behavioral approach, also studies behavioral patterns, although influenced by the context of the environment. The main models, exponents and characteristics of leadership can be found within this last approach (Table 1).

Transformational Leadership

The theories of House (1977) on charismatic leadership, and Burns (1978), on transformational leadership, laid the foundations of the transformational approach. On the one hand, House (1977) suggested the importance of a leader capable of transmitting and inspiring virtues to his followers towards a common goal. On the other hand, Burns (1978) included the term “transformational” which, while sharing similar objectives to charismatic leadership, relied on the skills and abilities of the leader, supported a more collective vision. Both theories linked differential traits and behaviors and situational variables in such a way that they raised the possibility of assuming different ways of leading depending on the context. However, they emphasized the advantages of a leadership of mutual commitment and oriented to the common good, in “doing” more than in “being”. In this context, Bass (1985) expands his studies on transformational leadership, defining four dimensions: (a) idealized influence, regarding characteristics of the leader with high morals and ethics, which produce consideration and loyalty in the follower; (b) motivation based on inspiration, where the behavior of the leader motivates and builds positive attitudes in his followers through actions and language; (c) intellectual stimulation, associated with the behavior that promotes critical and constructive look in his followers in order to generate innovative strategies and ideas; and (d) individualized consideration, which is related to the behavior of a leader that empathizes and recognizes the needs for growth and personal development of his followers. In this way, Bass (1985) articulated elements that at the time were studied separately.

This approach initiates a different way of approaching leadership. Before transformational leadership, the most influential studies were mostly related to the behavior and capacity leaders had to achieve objectives within the organization, from a realist-rationalist perspective, that is, from the “science of observable objects” according to Padrón (2007). However, research that included and combined the variables of emotional management and competences emerged, which allowed a different approach, more focused on the person as the engine of change.

Resonant Leadership and Competences

This approach is based on the work of Boyatzis (1982) and Goleman (1996) with The Competent Manager and Emotional Intelligence, respectively. On the one hand, Boyatzis conducted a study on more than 2000 managers, with which he proposed a model based on job-related competences necessary to sustain effective leadership. Regarding the term “competences”, although McClelland is considered one of the authors who proposed it as such in 1973, it can be noted that it was established as a common concept in organizations based on the publications of Boyatzis (Rey de Castro, 2019).

For his part, Goleman based his research on the management of emotions as an effective tool for decision making in all aspects of a person. In the organizational field, he focused on effective leadership, highlighting his work on the five components of emotional intelligence that make up a leader: “self-awareness”, “self-regulation”, “motivation”, “empathy” and “social skills”. He also identified six leadership styles that are present in an organization, where the challenge for the leader is to identify and assume the style necessary for the context (Goleman, 1998; 2000).

Later, Goleman, Boyatzis, and Mckee (2013) published together Primal Leadership, based on resonant and dissonant leadership. The first refers to positive leadership, which is based on the ability to “tune in” to the needs and expectations of the group from the emotional intelligence, hand in hand with the style that best suits the context. Meanwhile, dissonant leadership refers to the leadership that is not in line with the interests of the group or organization.

Effective High Performance Leadership

In the previous approaches, the role of leadership is observed from the perspective of the leader and his relationship with his followers, where his characteristics and level of influence, required to exercise effective leadership, stand out. However, Fernandez and Zambrano (2019) propose a methodology based on collaborative networks, where the role of leadership starts from the group towards the leader in a bidirectional sense, as a collectivity and through a cooperative structure. According to the authors, to achieve this synergy, and starting from the basis of transformational leadership and competences, leaders must develop a total of thirteen competences divided into three aspects or dimensions. The set of competences shown below is the one that defines effective high-performance leadership (Fernandez & Zambrano, 2019, p. 109). Moreover, this research aims to determine the relationship between the variables effective high performance leadership (X) -composed by three dimensions: personal leadership (X1), relational leadership (X2) and strategic organizational leadership (X3)- with the variable organizational climate (Y).

Dimension “Personal Leadership”

It is composed of three competences: self-awareness, self-management of emotions and initiative.

Competence “self-awareness”. This is related to the sense of taking responsibility for change and personal development, becoming aware of oneself. From a neuropsychology perspective, self-awareness is formed within the brain as it acquires certain morphological and cognitive development. Self-awareness results from a learning process in which the unique characteristics of aspects such as communication, symbology and the external environment intervene (Rivera & Rivera, 2018). Even though it has been studied from different disciplines, self-awareness is generally conceived as the ability to recognize oneself in connection with the environment, from a position of rationality and intertwined with emotional components (Mora, 2002; Ramírez-Goicochea, 2005; Tirapu-Ustárroz and Goñi-Sáez, 2016).

For Goleman (1996), self-observation and self-reflection make possible a balance in the contrast between rationality and the complex structure of feelings. For a leader, self-knowledge is the basis and foundation to try to generate some transformation in the team (Tan, 2012).

Competence “Self-management of Emotions”. Associated with the identification, knowledge, and meditation of our own emotions, and the continuous management of them. That is to say, it is the modulation and adaptation of emotions to the environment, promoting in the team the establishment of an emotional space in tune with the objectives proposed. It is the assumption of our own weaknesses and the offering of these to the group as input (Fernandez & Zambrano, 2019).

Emotions are a natural mechanism that appear as a reaction to some external stimulus. This reaction can generate a behavior or a feeling, and its intensity depends on the characteristics of each individual. The type of response to an emotion could be positive or negative, and even excessive (Ekman, 2003). In view of the above, it is essential for a leader to learn to manage his emotions.

Competence “Initiative”. This implies interacting continuously and energetically, suggesting and proposing scenarios to achieve expected results. Receiving, welcoming and building group proposals to complement, simplify and build new objectives together. Taking responsibility for the process and its consequences. High level of commitment (Fernandez & Zambrano, 2019).

The initiative of the members of an organization is presented as a result of the attitude assumed by each worker, in that they are oriented to maximize their own competences. Thus, the worker becomes a differentiating element between two individuals, since cognitive capacities can be matched and skills are achieved through practice (Küppers, 2011).

Regarding commitment, Goleman (1998) stresses the importance for the organization of having workers with initiative and a good attitude towards their work, who “often feel committed to the organizations that make that work possible. Committed employees are likely to stay with an organization even when they are pursued by headhunters waving money” (p. 8).

Dimension “Relational Leadership”

Composed of six competences: horizontality in relationships, dialogue and connectivity, inspiration, collaboration, judgement justification, and exercise of leadership.

Competence “Shows horizontality in relationships”. It refers to the ability to interrelate symmetrically and at the same level, regardless of the hierarchical role. The leader interacts with all workers on the same terms, showing willingness and open-mindedness. Muestra apertura y disponibilidad a la conversación del equipo fomenta una red de relaciones segura y confiable [Shows openness and availability to the team conversation and fosters a safe and reliable network of relationships] (Fernandez & Zambrano, 2019, p. 126).

Equal treatment among people, in general, is based on universal principles of respect and consideration for the other regardless of social differences, creed or thought. It is a way of interrelating showing self-respect and decorum (Maturana, 1996).

At the organizational level, the classic flow of interrelation among the members of an organization used to respond to a vertical structure based on its typically pyramidal organization chart (Toba & Gil, 2009). However, organizational structures have evolved over time towards an increasingly horizontal and informal reordering, especially at the communicational level. This perspective, increasingly present in organizations, redirects the gaze towards the person as the central axis for growth and sustainable development (García, 2015).

Competence “Generates dialogue and connectivity”. It is related to the ability to encourage and establish “interaction networks” within a positive and reliable space. It promotes and stimulates effective and shared communication, incorporating propositional and inquiring elements with a high level of correspondence. It focuses on building a matrix structure of cooperative work (Fernández & Zambrano, 2019).

This competence highlights the importance of effective dialogue as a basic integrative element, necessary to establish collaborative networks in the team and organization. Dialogue, as a form of communication, requires full awareness of its elements and power to be effective. Understanding the capacity of speech as a potential transforming element makes the person responsible and conscious. This, together with the ability to listen, from the position of the interlocutor, allows communication in connection with others (Echeverría, 2003).

Competence “Inspires to achieve outstanding performance”. It implies the ability to stimulate the collective towards commitment, emotional involvement, through purpose and meaning. Trasmite coherencia e inspiración. Es seguido por los demás por su credibilidad y convicción. Genera propósito trascendencia y orgullo de pertenencia [It conveys consistency and inspiration. It is followed by others for its credibility and conviction. It generates a purpose of transcendence and pride of belonging] (Fernández & Zambrano, 2019, p. 62).

The ability of a leader to transmit coherence and significance through his “being” and “doing” motivates the group, which generates positive attitudes that tend to be replicated. This behavior is inspiring and promotes collaborative teamwork in the pursuit of achieving the objectives proposed (Bass & Riggio, 2006). Inspiration fosters the personal growth of those around the leader, transforms them and guides them in the search for the common good (Bracho & García, 2013).

Competence “Promotes collaboration and team effectiveness”. This competence influences both internally, within the work team, and externally, in other units of the organizational structure, with the purpose of obtaining the desired results. In this sense, this leadership is based on collaborative work, high rotation of experience and knowledge, and the promotion and recognition of the team strengths as the foundation for decision making. It prioritizes the “us” over the personal aspects as well as the success of the team (Fernandez & Zambrano, 2019).

This approach supports the importance of optimizing the interpersonal relationships among team members, directing the work mystique to all members of the organization with the purpose of generating organizational collective intelligence, where connection and trust exist. It is essential to obtain the cooperation of the members of the organization through respect and authority inspired by others, which is possible through positive and constructive communication in search of emotional and rational alignment and involvement in the challenges of the team (Vergara, 2016). In this approach, the position of the collaborator in the interaction with the leader is important, where the role of the leader is fundamental in the relationship, since the response of the collaborator depends on his performance (Cardona, 2000).

An important aspect of relational leadership is promoting a collaborative culture, for example, through the recognition of the small and large successes of team members, pondering the significance of individual efforts in contributing to the achievement of objectives, which in the end are shared purposes. Likewise, in the management of work teams, it is praiseworthy to be aware of the events of the near and distant environment of the organization without neglecting, within the team, the search for flexibility in human relations through empathy and the promotion of shared purposes (Blanchard, Ripley & Parisi-Carew, 2015).

Competence “Justifies his judgements”. This competence is based on the trust, knowledge and experience that the leader inspires in the team. This competence allows explaining the directionality of the organizational objectives, their purpose and the foundations on which they are based, which favors efficient performance and eliminates insecurity, doubts and uncertainty (Fernandez & Zambrano, 2019).

Communication is a capacity that must be managed in organizations. In this sense, the capacity of communication is significant, it is closely related to the ability to bond with others through active listening, assertive communication and social skills that contribute directly to achievements. Communication generates a sense of belonging (Echeverría, 2003). Moreover, for leaders, it is a process of reflection that allows establishing judgments that will be shared with team members and that should generate a sense of commitment and belonging (Gardner, 1995).

Leaders leading impact teams base their decisions on pre-established judgments that are directly related to the success of the organization, decisions in which team members have had an important contribution, that is, all team members have had direct participation (Clark, 2016).

Competence “Exercises firm and close leadership”. The purpose of this competence is to balance the behaviors, capabilities, experiences, and values of each and every one of the organization members and direct them towards organizational results; in short, the leader is a facilitator who discovers skills and allows these to be made available to the team (Fernandez & Zambrano, 2019).

The development of firm and close leadership, according to studies conducted by Zenger and Folkman (2011), demands result orientation, personal capabilities, personality, change leadership and personal skills; in this sense, this capacity is typical of those who lead high performance teams, where resonant leadership has a natural ground and where the emotional state of its members is conclusive for its operation as well as for organizational success. An organization whose agenda includes the emotional health of its members will present possibilities for creativity and innovation, which means that it will be a favorable space for their growth (Losada, 2008).

Others consider that relational leadership is based on fundamental pillars such as: fostering relationships of closeness and trust; achieving collaboration and authority in others; and motivating and achieving the commitment of team members (incolid, 2019).

Dimension “Organizational-Strategic”

This consists of four competences: “defines and directs high standard results”, “shows strategic capacity”, “promotes alternative approaches”, “applies constructive and effective solutions” and “promotes adaptive change”.

Competence “Defines and directs high standard results”. This leadership is linked to strategic organizational performance, which helps the team achieve its results (Rozo-Sánchez, Flórez-Garay, & Gutiérrez-Suárez, 2019). It is characterized by establishing and directing high performance results based on collaborative work and the permanent evaluation and monitoring of the planned milestones and indicators and their results (Fernández & Zambrano, 2019).

High performance leaders must demonstrate to their team that they have the competences to lead teams that, according to the perspective of the organization, are responsible for achievements for business growth (Uribe, Molina, Contreras, Barbosa, & Espinoza, 2013). The opposite would cause demotivation and perhaps even disintegration of the team, without taking into account the consequences of personal and economic prestige for the company. The leader must transmit to his team members the organizational mission and vision and the meaning of high performance (McCord, 2014).

Being high standard results, ethics is an important aspect, which is directly related to the character formation of the team members, of the organization itself, which will allow horizontal credibility among its members (Cortina, 2017).

Competence “Shows strategic capacity and promotes alternative approaches”. Effective leadership develops a contextual analysis of the organization. On that basis, it establishes possible scenarios and proposes solutions. The ability of reflection allows the leader to read the reality of corporate influence (Fernandez and Zambrano, 2019). This strategic capacity allows the leader to direct organizational goals by using tools according to the scope of action, all aimed at the evolution of the organization (Fierro, 2012).

In these times where complexity and uncertainty seem to be common ground, the performance of strategic organizational leadership should focus on reflective analysis as well as strategic action; foresight is a powerful tool. However, a modern view of the organizations is important to assume the strategy that best suits the business (Pulgarín & Rivera, 2012).

Competence “Applies constructive and effective solutions”. Organizational strategic leadership provides effective responses to organizational problems on a permanent basis through collaborative networks, through which it demonstrates its results. It also recognizes the existing potentialities and puts them at the service of the team. The commitment of its members to the effectiveness of pre-established results is a common denominator (Fernandez & Zambrano, 2019). This type of leadership takes advantage of the advancement in information and communication technologies for the creation of formal and informal networks that transcend the organization and could be useful when making decisions (Pareja, 2017).

Competence “Promotes adaptive change”. The leader is characterized by having a permanent look at innovation, promoting change, and motivating teams to look beyond the routine, so that he inspires change towards paradigms that favor the growth of the organization. High impact leaders have a holistic view of the total, technical and political reality; their decisions have the required support (Fernandez & Zambrano, 2019). They also have a high capacity to adapt to changes, can lead teams in organizations of different nature and lead multidisciplinary teams. Conflicts are understood as an opportunity (Pareja, 2017) and motivate towards analytical and critical thinking of team members as a measure to encourage the creative and propositional spirit (Limsila & Ogunlana, 2008).

Eichholz (2015) says that the outstanding performance leader challenges problems and people in search of creative answers. He does not give solutions, he incentivizes participation and motivates solutions to flow from the team; his focus is the personal growth of individuals.

Organizational Climate

Under the perspective of measuring those attributes of the work environment that determine the characteristics of a company, and how the personal perceptions of workers influence their behaviors, the measurement of organizational climate is a practice whose use dates back to the twentieth century as a source of research, diagnosis, internal analysis and improvement plans. Based on LEAD, Liderazgo Efectivo para el Alto Desempeño (Effective Leadership for High Performance) (Fernandez & Zambrano, 2019), the leader is called to facilitate working conditions and environments for the achievement of social and economic results, so that it lets the connection between the leader and the organizational climate be evident on its own.

Organizational climate is a fundamental variable from a strategic point of view. The findings related to its relationship with high performance leadership will have a direct impact on business results. In this way, it is validated that the organizational climate influences work behavior, in the face of employee attitudes and expectations (Lapo, 2018).

The diversity of the population within the organization (age, gender, type of position, specialty, time on the job, culture, academic degree, or others) creates the need to know their perceptions and motivations. This allows establishing specific actions that are related to the findings, so that it makes visible a formal interest in their needs, in order to promote the effectiveness, efficiency and effectiveness of the results of the company. Thus, the diagnosis of the organizational climate, oriented towards the continuous improvement of the company, is a formal tool for decision making. Its periodicity (annual, half-yearly) will allow establishing an evolutionary curve and will be an indicator of the results of the programs and actions deployed, which will establish a continuous learning process that not only involves the human resources area, but also each team leader and the organization in general.

Developing the capacity to adapt on a personal and organizational level is one of the greatest challenges and it is studied as a social phenomenon. For example, in the United States, this context is known as VUCA (volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity) and in the United Kingdom as TUNA (turbulence, uncertainty, novelty and ambiguity). Precisely, under this reality, organizations and human beings are oriented to review and enhance those factors that are under their control (Tessore, 2020). According to a report by Hay Group (2015), which included the participation of 3,800 leaders in Peru, the leadership style displayed by managers can have an impact of up to 70% on the organizational climate and, in turn, have an impact of up to 30% on business performance.

Ucrós and Gamboa (2010) investigated organizational climate by analyzing 13 representative authors over a period of 40 years, since the late 1970s, with the aim of finding the most representative factors. They concluded on the presence of three main factors as dimensions of organizational climate: individual, relational and group, and organizational factors. These factors or dimensions are the ones that generate interrelation models within the concept of organizational climate (Griffin & Moorhead, 2010; Brunet, 1997).

Dimension “Individual Factors”. Composed of five factors or sub-dimensions: commitment, satisfaction-pride, performance, motivation, and stress-adaptation. Commitment, related to the level of awareness of the employees regarding their sense of belonging and responsibility towards the organization, is born through a psychological process between the individuals and the organization, affected by components such as trust and leadership, and has an impact on turnover and employee satisfaction (Tejero-González & Fernández-Díaz, 2009; Castro, 2006). Satisfaction-pride is related to the attitudes of workers regarding their perception of their job, role in the organization and how they feel about it (Bravo, Peiró & Rodríguez, 1996); the higher the satisfaction, the greater the sense of belonging and pride, which is linked to job satisfaction as a key factor for the achievement of objectives and a positive organizational climate (Peña, Olloqui & Aguilar, 2013). Performance is a factor directly related to the achievement of organizational objectives; likewise, it has been found that the work climate, directly influences job performance (Griffin & Moorhead, 2010; Bulnes, Ponce, Huerta, Elizalde, Santivañez, Delgado & Álvarez, 2004; Chiavenato, 2006). Motivation is like an impulse of actions or inactions (Robbins, 1999) that derive from the desire, need or free will of the person and result in visible behaviors. Finally, the stress-adaptation factor refers to the physical and emotional management of work demands, from which arises the capacity to adapt to the work situation, as well as the display of attitudes (Rodríguez, 2005). It has been found that certain levels of stress are recommended to develop the creativity in workers, while a very low level of stress generates apathy and discouragement (Sardá-Junior, Legal & Jablonski-Junior, 2004).

Dimension “Relational and group factors”. It consists of four factors or sub-dimensions: leadership, trust in the immediate boss, teamwork-collaboration-cooperation and support-communication. Leadership is related to the determining role it plays in the development of a positive or negative climate (Peraza & Remus, 2004; Ponce, Pérez, Cartujano, López, Álvarez & Real, 2014). Trust in the immediate boss is determined through the worker's perception of the behavior, conduct, actions and form of leadership of his boss (Méndez, 2005); in this regard, it is evident that if the level of trust is low, there is a tendency to work in an environment of constant tension; on the contrary, when the level of trust is high, communication and participation at all levels is encouraged (Robbins, 1999). The teamwork-collaboration-cooperation factor refers to establishing the advantage of shared knowledge in the company, which strengthens the process of human relations, interrelationships, the sense of belonging and the contribution to collective objectives (Méndez, 2005). The last factor in this dimension is support-communication, which is related to the support provided by the organization and the work environment, as well as the quality of communication, its closeness and effectiveness.

Dimension “Organizational Factors”. Composed of thirteen factors or sub-dimensions: policies-strategy, infrastructure-equipment, norms-regulations, health-safety, recognition, personnel development, salary-benefits-incentives, work-life balance, diversity-inclusion, integrity, customer management, sustainability, COVID-19. The policy-strategy factor is related to the dissemination of the policies, the clarity of where the organization is going, how it achieves its objectives and how it communicates this to people. With respect to infrastructure-equipment, this factor corresponds to the minimum working conditions required by workers to perform their tasks. The norms-regulations include the formal norms, and the tacit premises that are linked to the culture of the organization and are the basis for decision making (Rodriguez, 2005). The health-safety factor refers to the coherence of the focus on people, that is, the generation of conditions, capabilities, programs, processes and procedures that guarantee the care of workers. Along the same lines, recognition is considered a main factor for worker satisfaction (Herzberg, 2003); it is also a social reinforcement of impact that contributes positively to the perception of the organizational climate. Personnel development is composed of the development and growth needs of each worker, while the salary-benefits-incentives factor responds to the tangible that the worker receives, in the perception of fairness of the staff, regarding what they receive from the organization and also what others receive (Juarez & Carrillo, 2014). It is important to study work motivation in order to propose compensation alternatives that do not only cover the monetary factor, so as to achieve a greater impact on the worker compensation and benefits scale (Brunet, 1997).

Work-life balance is related to the space for the attention of the affective, family and personal world of each worker, which impacts their well-being and performance (Casas et al., 2002). Diversity-inclusion represents the respect and incorporation of the sense of accepting differences and discovering the potential in each individual; thus, the organization acquires value, prestige and modernity. The integrity factor implies consistency between what is said and what is done, as well as ethics, transparency and trust. Customer management refers to the perception by the employee of the quality of the product and services offered, which is implicitly linked to pride and sense of belonging. Likewise, sustainability is the visible commitment to the communities, the environment, and strategic partners. In this regard, Caro and Ojeda (2019) found a positive and high correlation between sustainability and work climate. Finally, the COVID-19 factor was included, since it was considered influential in the perception of workers in relation to the measures adopted by the company, and their impact on personal and work life.

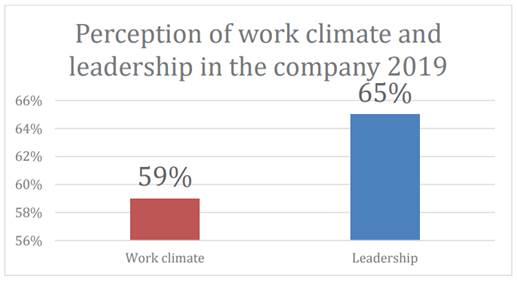

The company under study has more than five decades operating in the industrial sector and a total of 280 workers. In 2019, a new team took over management and carried out a restructuring process. Since then, they have developed organizational climate studies, whose first diagnosis found 59% of respondents with a positive perception of the work climate, while 65% noted the presence of some kind of leadership (Figure 1). This context highlighted the need to design leadership development strategies; thus, the program was implemented for managers and first-line managers during the first year. The following year, the program was extended to middle management, accompanied by an emotional health and safety work plan for all employees. In this new approach to human talent as a strategy to achieve the new institutional objectives, leadership was considered as a factor that could have a significant impact on the improvement of organizational climate indicators, based on the competencies detailed above.

Source: Prepared by the authors based on data from the organization.

Figure 1 Perception of Work Climate and Leadership in the Company in 2019.

This article seeks to contribute to the knowledge of organizational climate management in public or private activity. Likewise, it is considered an important contribution to the academy because it covers aspects of recent treatment under the approach presented. This is achieved through a different look that offers effective leadership for high performance, whose center of attention is not the leader, but the involvement within the work team of the one who exercises leadership “from the network of team relationships” (Fernandez & Zambrano, 2019, p. 11) and applying 13 components, where the “us” prevails over the “I”; that is, starting from the premise of the role of the leader as a facilitator of conditions for the achievement of results. Under this approach, responsibility is assumed to create a safe, challenging, collective, collaborative, and continuous learning environment. In this study, we intend to determine the correlation between leadership and organizational climate.

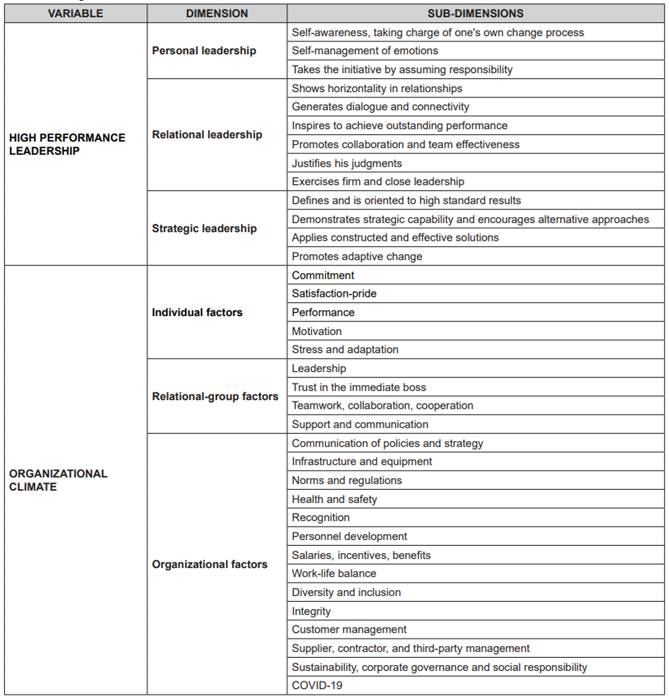

Table 2 Design of Variables, Dimensions, and Sub-Dimensions.

Source: Prepared by the authors, adapted from Fernández and Zambrano (2019) for high performance leadership and from Ucros and Gamboa (2010) for organizational climate.

Table 2 shows how the variables and dimensions were designed. The relationship between the organizational climate variable and personal leadership (first dimension), relational leadership (second dimension) and strategic organizational leadership (third dimension) were proposed as specific hypotheses. The results obtained and the discussion of the conclusions reached are presented below.

METHODOLOGY

The design of the research is non-experimental and correlational. Data were obtained through structured surveys. For the main variable, “high performance leadership” (formed by dimensions “personal leadership”, “relational leadership”, and “strategic organizational leadership”), based on the work of Fernandez and Zambrano (2019), a survey was designed based on 35 items. For the second variable, “organizational climate”, the dimensions of Ucrós and Gamboa (2010) (“personal factors”, “relational factors” and “organizational factors”) were used, for which 45 items were designed and adapted. The study population is made up of the total number of workers who are in charge or personnel at the company. In other words, a sample was formed with 108 workers who, by the nature of their position, exercise some type of leadership.

For data collection, two questionnaires were prepared, one for each variable, using a Likert scale, with a minimum score of 1 and a maximum of 5. The surveys were taken at the company, after an orientation talk and on two different dates. Data were obtained for each variable by date, and were assigned a random number or code between 1 and 180. To determine the validity of the surveys, they were submitted to the expert judgment of four specialists in the field of human resources. To measure reliability, Cronbach's Alpha indicator was applied. The internal reliability result was 0.989 for the variable “high performance leadership” and 0.956 for “organizational climate”.

RESULTS

The results were obtained at the beginning of December 2021, after a leadership training shop as described above. The descriptive findings are shown below.

Figure 2 shows that 41.7% of the workers surveyed have a “high” perception of the variable “high performance leadership”, 34% consider it “very high” and only 10% rated it as “low”. 75.9% consider that their leaders sustain high performance leadership.

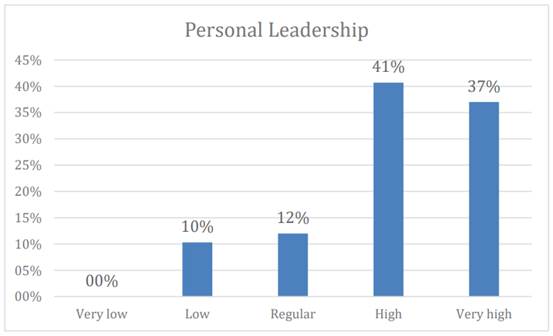

Regarding the first dimension, “personal leadership”, Figure 3 shows that 40.7% of the respondents have a “high” perception; 37% have a “very high” perception; 12% have a “regular” perception; and 10% have a “low” perception. A total of 77.7% have a perception between “high” and “very high”, while 22.3% have a perception between “low” and “Regular”.

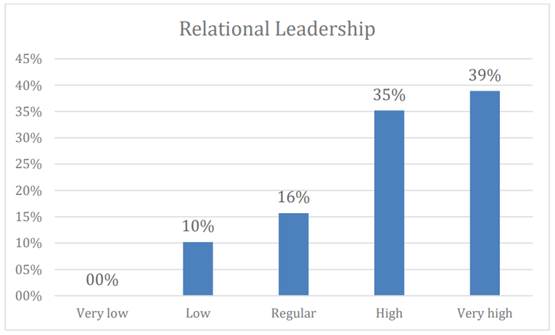

In the case of the second dimension, “relational leadership”, Figure 4 shows the descriptive results, where 38.9% of the workers indicated having a “very high” perception of relational leadership in their leaders; 35.2%, “high”; 15.7%, “regular”; and 10.2%, “low”. Likewise, 74.1% have a perception between “high” and “very high” and 25.9% consider that personal leadership has a level between regular and low.

Regarding the third dimension, organizational-strategic leadership, Figure 5 shows that 48.1% of the workers have a “high” perception; 26.9%, “very high”; 13.9%, “regular”; and 10.2%, “low”. Similarly, 75% of the respondents have a perception between “high” and “very high”, while 25% have a perception between “regular” and “very low”.

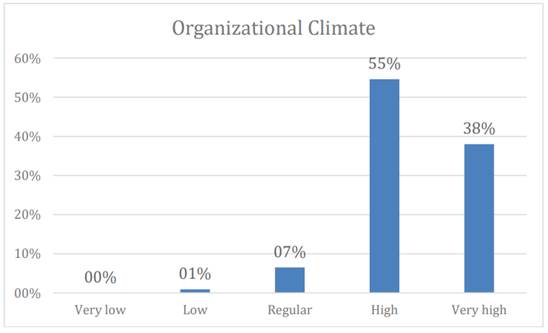

In the “organizational climate” variable, Figure 6 shows that 38% of the workers have a “high” perception; 54.6%, “very high”; 6.5%, “regular”; and 0.9%, “low”. Thus, 92.6% of respondents have a perception between “high” and “very high”, while 7.4% have a perception between “regular” and “very low”.

Hypothesis Test

High performance leadership is related to the organizational climate of the company.

Hypothesis

The test of the general hypothesis of the variables “high performance leadership” and “organizational climate” presents the following result:

H0: r = 0. There is no significant relationship between high performance leadership and organizational climate.

H1: r ≠ 0. There is a significant relationship between high performance leadership and organizational climate.

Table 3 shows a high positive correlation (0.812) with a significance level of 0.01 between high performance leadership and organizational climate. Therefore, the null hypothesis that there is no significant relationship between the variable “high performance leadership” and organizational climate is rejected.

Specific Hypothesis One

H0: r = 0. There is no significant relationship between personal leadership and organizational climate.

H1: r ≠ 0. There is a significant relationship between personal leadership and organizational climate.

Table 3 Spearman’s Rho Values for High Performance Leadership and Organizational Climate.

| Value | |

|---|---|

| Correlation coefficient | 0.812 |

| N | 108 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 |

Source: Prepared by the authors based on questionnaire applied to the sample in the year 2021, obtained from SPSS V25 software results.

Table 4 shows a high positive correlation (0.680) with a significance level of 0.01 between personal leadership and organizational climate. Therefore, the null hypothesis that there is no significant relationship between the personal leadership dimension and organizational climate is rejected.

Specific Hypothesis Two

H0: r = 0, There is no significant relationship between relational leadership and organizational climate.

H1: r ≠ 0, There is a significant relationship between relational leadership and organizational climate.

Table 4 Spearman's Rho Values for Personal Leadership and Organizational Climate.

| Value | |

|---|---|

| Correlation coefficient | 0.680 |

| N | 108 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 |

Source: Prepared by the authors based on questionnaire applied to the sample in the year 2021, obtained from SPSS V25 software results.

There is a high positive correlation (0.795) with a significance level of 0.01 between relational leadership and organizational climate. Therefore, the null hypothesis that there is no significant relationship between the relational leadership dimension and organizational climate is rejected (Table 5).

Specific Hypothesis Three

H0: r = 0, There is no significant relationship between organizational/strategic leadership and organizational climate.

H1: r ≠ 0, There is significant relationship between organizational-strategic leadership and organizational climate.

Table 5 Spearman's Rho Values for Relational Leadership and Organizational Climate.

| Value | |

|---|---|

| Correlation coefficient | 0.795 |

| N | 108 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 |

Source: Prepared by the authors based on questionnaire applied to the sample in the year 2021, obtained from SPSS V25 software results.

Table 6 shows a moderate positive correlation (0.425) with a significance level of 0.01 between organizational-strategic leadership and organizational climate. Therefore, the null hypothesis that there is no significant relationship between the strategic organizational leadership dimension and organizational climate is rejected.

DISCUSSION

The results of the study show that high performance leadership and organizational climate are significantly related in the organization, which was validated by means of the T. Spearmann correlation tests, which proved the relationship of the variables.

This direct relationship is confirmed by Hernandez, Duana and Polo (2021) from a leadership styles approach. They mention that a type of leadership in which poor communication is the main attribute results in an unstable organizational climate with a low level in its indicators. Likewise, Parra and Rocha (2021) evidenced a high and positive correlation level (Pearson's coefficient 0.86) between leadership styles and organizational climate. “Closed” and “authoritarian” styles were related to low levels of organizational climate. On the other hand, Saavedra, Reyes, Trujillo, Alfaro and Jara (2019) executed their study based on the types of managerial leadership, determining a direct and positive relationship with organizational climate.

Personal leadership and strategic organizational leadership have a high positive correlation with organizational climate. Therefore, it is understood that a positive impact will be obtained in the organizational climate indicators as long as the development of personal leadership is promoted in leaders and workers, considering self-management and initiative taking, as well as the development of competencies focused on the search for high standard results, strategic capacity, adaptability to changes and collaborative search for work solutions.

Thus, Goleman (1998) states that companies that develop the muscle of emotional intelligence (from the self-knowledge of their people, their self-regulation and self-management) will be able to guide decision making in a sensible way and impact the results of the organization.

In the case of relational leadership, it is evident that it is the dimension with the highest level of correlation with the organizational climate, compared to personal leadership and organizational-strategic leadership. Therefore, relational leadership is considered the main deployment of actions whose impact will be on a larger scale where, for example, the leader must focus on strengthening the social field, from horizontality, from the consistency of the example and from inspiring to achieve outstanding performance, as well as promoting dialogue and connectivity, collaboration and strengthening of team membership, and firmness to guide to excellence. This, taking into account the necessary closeness from the personal aspect, which generates the predominant contribution to the improvement of the organizational climate.

This is why Goleman (2000) ratifies the value of the “work atmosphere” from leadership through a set of twenty capacities or competencies, distributed in four groups: self-awareness, self-management, conscience and social skills. These capabilities are transversal to all leadership styles, which are related to the organizational climate.

CONCLUSIONS

The research shows that high performance leadership and organizational climate are significantly related. It is concluded that there is a positive and high relationship of 0.812.

Regarding personal leadership and organizational climate, it is evident that they are significantly related, with a high positive result of 0.501. The analysis shows that the general perception of employees with respect to personal leadership is positive with 77.7%.

This study shows that relational leadership and organizational climate are significantly related, with a high positive relationship of 0.795. According to the results, the workers responded and expressed a positive perception of 74%.

There is a moderate relationship between organizational strategic leadership and organizational climate (a moderate relationship of 0.425). The employees surveyed showed a 75% positive perception.

With respect to the organizational climate variable, according to the analysis, 92.6% have a positive perception.

In the high performance leadership variable, 76% of employees had a perception between “high” and “very high” in 2021.

The results of this research can be used as a basis for the design of strategies oriented to the development of “high performance leadership” which, on the one hand, allow organizations to put into practice approaches whose results could be positive in the way of optimizing the organizational climate and, on the other hand, contribute to the Academy, so that other researchers choose to make use of the instruments that have the validity and reliability that scientific research demands.

REFERENCIAS BIBLIOGRÁFICAS

Bass, B. M. (1985). Leadership and performance beyond expectations. New York, NY, EE. UU.: Free Press. [ Links ]

Bass, B. M. (1990). Bass & Stogdill's Handbook of Leadership: Theory, Research, and Managerial Applications (3 rd ed.). Nueva York, NY, EE. UU.: Free Press. [ Links ]

Bass, B., y Riggio, R. (2006). Transformational Leadership (2nd ed.). Mahwah, NJ, EE. UU.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [ Links ]

Blanchard, K., Ripley, J., y Parisi-Carew, E. (2015). La colaboración comienza con Usted. Buenos Aires, Argentina: Paidós. [ Links ]

Boyatzis, R. (1982). The Competent Manager: A Model for Effective Performance. Nueva York, NY, EE. UU.: Jhon Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Bracho, O., y García, J. (2013). Algunas consideraciones teóricas sobre el liderazgo transformacional. TeloS: Revista de Estudios Interdisciplinarios en Ciencias Sociales, 15(2), 165-177. [ Links ]

Bravo, M. J., Peiró, J. M., y Rodríguez, I. (1996). Satisfacción Laboral. En J. M. Peiró y F. Prieto (Eds.), Tratado de psicología del trabajo (Vol. 1, pp. 343-394). Madrid, España: Síntesis S.A. [ Links ]

Brunet, L. (1997). El clima de trabajo en las organizaciones. Definición, diagnóstico y consecuencias. México D. F., México: Editorial Trillas. [ Links ]

Bulnes, M., Ponce, C., Huerta, R., Elizalde, R., Santivañez, W., Delgado, E., y Álvarez, L. (2004). Percepción del clima social laboral y de la eficiencia personal en profesionales de la salud del sector público de la ciudad de Lima. Revista de Investigación en Psicología, 7(2), 39-64. [ Links ]

Burns, J. (1978). Leadership. Nueva York, NY, EE. UU.: Harper & Row. [ Links ]

Cardona, P. (2000, febrero). Liderazgo relacional. Universidad de Navarra, División de Investigación IESE. https://media.iese.edu/research/pdfs/DI-0412.pdf [ Links ]

Caro, C., y Ojeda, J. (2019). Responsabilidad social y clima organizacional en la Universidad Autónoma de Nayarit. Proyecciones, (13), 14-28. [ Links ]

Casas, J., Repullo, J., Lorenzo, S., y Cañas, J. (2002). Dimensiones y medición de la calidad de vida laboral en profesionales sanitarios. Revista de Administración Sanitaria, 6(23), 143-160. [ Links ]

Castro, A. (2006). Teorías implícitas del liderazgo, contexto y capacidad de conducción. Anales de psicología, 22(1), 89-97. http://hdl.handle.net/10201/8082 [ Links ]

Chiavenato, I. (2006). Introducción a la teoría general de la administración. México D. F., México: Mc Graw-Hill/Interamericana Editores S.A. [ Links ]

Clark, T. (2016). Leading with Character and Competence: Moving Beyond Title, Position, and Authority. Oakland, CA, EE. UU.: Berrett-Koehler Publishers. [ Links ]

Cortina, A. (2017). ¿Para qué sirve realmente...? La Ética. Barcelona, España: Paidós. [ Links ]

Echeverría, R. (2003). Ontología del lenguaje. Santiago de Chile, Chile: Comunicaciones Noreste. [ Links ]

Eichholz, J. C. (2015). Capacidad adaptativa: Cómo las organizaciones pueden sobrevivir y desarrollarse en un mundo cambiante. Bogotá, Colombia: Ediciones de la U. [ Links ]

Ekman, P. (2003). El rostro de las emociones. Barcelona, España: RBA BOLSILLO. [ Links ]

Estrada, S. (2007). Liderazgo a través de la historia. Scientia et Technica, 13(34), 343-348. [ Links ]

Evans, M. G. (1970). The effects of supervisory behavior on the path-goal relationship. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance 5(3), 277-298. https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-5073(70)90021-8 [ Links ]

Fernández, I., y Zambrano, R. (2019). Liderazgo efectivo para el alto desempeño (LEAD). Madrid, España: Ediciones Urano. [ Links ]

Fiedler, F. (1978). The Contingency Model and the Dynamics of the Leadership Process. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Vol. 11, pp. 59-112). Nueva York, NY, EE. UU.: Academic Press. [ Links ]

Fiedler, F. E., y Garcia, J. E. (1987). New Approaches to Effective Leadership: Cognitive Resources and Organizational Performance. Nueva York, NY, EE. UU.: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Fierro, I. (2012). El rol del liderazgo estratégico en las organizaciones. Saber, ciencia y libertad, 7(1), 119-123. [ Links ]

García, S. (2015). Perspectiva societario-económica del trabajo. La evolución del mundo del trabajo y su dimensión ético-empresarial. Instituto de Dirección y Organización de Empresas (IDOE) de la Universidad de Alcalá. [ Links ]

Gardner, H. (1995). Inteligencias Múltiples. La Teoría en la Práctica. Barcelona, España: Paidós. [ Links ]

Goleman, D. (1996). La inteligencia Emocional. Por qué es más importante que el cociente intelectual. Buenos Aires, Argentina: Zeta. [ Links ]

Goleman, D. (1998). What makes a leader? Harvard Business Review, 76(6), 93-102. [ Links ]

Goleman, D. (2000). Leadership that gets results. Harvard Business Review, 1-15. [ Links ]

Goleman, D., Boyatzis, R., y Mckee, A. (2013). El líder resonante crea más. Buenos Aires: Debolsillo. [ Links ]

Griffin, R., y Moorhead, G. (2010). Comportamiento organizacional. Gestión de personas y organizaciones (9ª ed.). Ciudad de México, México: Cengage Learning Editores S.A. [ Links ]

Hay Group. (2015). Estudios de clima laboral. Lima, Perú: Hay Group. [ Links ]

Hernández, T., Duana, D., y Polo, S. (2021). Clima organizacional y liderazgo en un instituto de salud pública mexicano. Revista cubana de salud pública, 47(2). [ Links ]

Herzberg, F. (2003). Una vez más: ¿Cómo motiva a sus empleados? Harvard Business Review , 81(1), 67-76. [ Links ]

House, R. (1971). A Path Goal Theory of Leader Effectiveness. Administrative Science Quarterly, 16(3), 321-339. https://doi.org/10.2307/2391905 [ Links ]

House, R. (1977). A 1976 Theory of Charismatic Leadership. En J. Hunt y L. Larson (Eds.), Leadership. The cutting edge. Carbondale, IL, EE. UU.: Southern Illinois University Press. [ Links ]

incolid. (2019, 19 de octubre). Los 3 pilares del liderazgo relacional. https://www.incolid.com/l/3-pilares-liderazgo-relacional/ [ Links ]

Juárez, O., y Carrillo, E. (2014). Administración de la compensación, sueldos, salarios, incentivos y compensaciones. México D. F., México: Grupo Editorial Patria. [ Links ]

Kerr, S., y Jermier, J. M. (1978). Substitutes for leadership: Their meaning and measurement. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 22(3), 375-403. [ Links ]

Kirpatrick, S., y Locke, E. (1991). Leadership: Do Traits Matter? Academy of Management Executive, 5(2), 48-60. [ Links ]

Küppers, V. (2011). El efecto Actitud. Barcelona, España: Ediciones Invisibles. [ Links ]

Lapo, M. (2018). Influencia del clima organizacional en las actitudes laborales y en el comportamiento pro-social de los profesionales de la salud. (Disertación para obtener el grado de doctor). Pontifica Universidad Católica del Perú, Lima. [ Links ]

Limsila, K., y Ogunlana, S. (2008). Performance and Leadership Outcome Correlates of Leadership Styles and Subordinate Commitment. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 15(2), 164-184. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/09699980810852682 [ Links ]

Losada, M. (2008). Si quieres florecer. Psicología Organizacional Humana, 1(2), 121-125. [ Links ]

Maslow, A. (1943). A Theory of Human Motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370-396. [ Links ]

Maturana, H. (1996). El sentido de lo humano. Santiago de Chile, Chile: Paidós. [ Links ]

Mayo, E. (1933). The Human Problems of an Industrial Civilization. Nueva York, NY, EE. UU.: The Macmillan Company. [ Links ]

McCord, P. (2014). How Netflix Reinvented HR. Harvard Business Review, (January-February 2014). [ Links ]

Méndez, C. (2005). Clima organizacional en empresas colombianas 1980-2004. Universidad Empresa, 4(9), 100-121. [ Links ]

Misumi, J., y Peterson, M. (1985). The Performance-Maintenance (PM) Theory of Leadership: Review of a Japanese Research Program. Administrative Science Quarterly, 30(2), 198-223. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393105 [ Links ]

Mora, F. (2002). Cómo funciona el cerebro. Madrid, España: Alianza Editorial. [ Links ]

Padrón, J. (2007). Tendencias Epistemológicas de la Investigación Científica en el Siglo XXI. Cinta de Moebio, (28), 1-28. [ Links ]

Pareja, S. (2017). Liderazgo colaborativo: atreverse a quebrantar el "statu quo". Observatorio de Recursos Humanos y RR.LL., (octubre de 2017), 10-12. https://www.peoplematters.com/Archivos/Descargas/Docs/Docs/articulos/PM_Papel/2017/Octubre/1710_ORH127.pdf [ Links ]

Parra, M., y Rocha, G. (2021). Liderazgo como prospectiva del clima organizacional en el sector hotelero. Revista de ciencias sociales, 27(2), 217-227. [ Links ]

Peña, M., Olloqui, A., y Aguilar, A. (2013). Relación de Factores en la Satisfacción Laboral de los Trabajadores de una Pequeña Empresa de la Industria Metal-Mecánica. Revista Internacional de Administración & Finanzas, 6(3), 115-128. https://www.theibfr.com/download/riaf/2013-riaf/riaf-v6n3-2013/RIAF-V6N3-2013-9.pdf [ Links ]

Peraza, Y., y Remus, M. (2004). Clima organizacional: conceptos y experiencias. Transporte, desarrollo y medio ambiente, 24(1), 27-30. [ Links ]

Ponce, P., Pérez, S., Cartujano, S., López, R., Álvarez, C., y Real, B. (2014). Liderazgo femenino y clima organizacional, en un instituto universitario. Global Conference on Business and Finance Proceedings, 9(1), 1031-1036. [ Links ]

Pulgarín, S., y Rivera, H. (2012). Las herramientas estratégicas: un apoyo al proceso de toma de decisiones gerenciales. Criterio Libre, 10(16), 89-114. [ Links ]

Ramírez-Goicochea, E. (2005). Orígenes complejos de la conciencia: hominización y humanización. En L. Álvarez Munarriz (Ed.), La conciencia humana: perspectiva cultural (pp. 93-135). Barcelona, España: Anthropos. [ Links ]

Rey de Castro, D. (2019). Gestión por competencias y su relación con el clima laboral en una empresa de servicios, consultoría y outsourcing, Lima 2017. (Tesis de maestría). Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Lima. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12672/16554 [ Links ]

Rivera, A., y Rivera, S. (2018). Estudio transdisciplinario sobre la autoconciencia. Ludus Vitalis, 25(48), 155-180. [ Links ]

Robbins, S. (1999). Comportamiento organizacional. México: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Rodríguez, D. (2005). Diagnóstico organizacional. Ciudad de México, México: Alfaomega. [ Links ]

Rozo-Sánchez, A., Flórez-Garay, A., y Gutiérrez-Suárez, C. (2019). Liderazgo organizacional como elemento clave para la dirección estratégica. Aibi revista de investigación, administración e ingeniería, 7(2), 62-67. https://revistas.udes.edu.co/aibi/article/view/1669/1859 [ Links ]

Saavedra, E., Reyes, M., Trujillo, J., Alfaro, C., y Jara, C. (2019). Liderazgo y clima organizacional en trabajadores de establecimientos de salud de una microred de Perú. Revista cubana de salud pública, 45(2). [ Links ]

Sardá-Junior, J., Legal, E., y Jablonski-Junior, S. (2004). Estresse: conceitos, métodos, medidas e possibilidades de intervenção. Sao Paulo, Brasil: Casa do Psicólogo. [ Links ]

Shartle, C. (1956). Executive Performance and Leadership . Hoboken, NJ, EE. UU.: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Stogdill, R. (1963). Manual for the Leader Behavior Description Questionnaire, Form XII. [ Links ]

Tan, C.-M. (2012). Busca en tu interior: Mejora la productividad, la creatividad y felicidad. Barcelona, España: Planeta S.A. [ Links ]

Taylor, F. (1911). The Principles of Scientific Management. Manhattan, NY, EE. UU.: Harper & Brothers. [ Links ]

Tejero-González, C., y Fernández-Díaz, M. (2009). Medición de la satisfacción laboral en la dirección escolar. Revista electrónica de investigación y evaluación educativa, 15(2), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.7203/relieve.15.2.4160 [ Links ]

Tessore, C. (2020). Cambios de paradigma en contextos Vuca y Tuna. [ Links ]

Tirapu-Ustárroz, J., y Goñi-Sáez, F. (2016). El problema cerebro-mente (II): sobre la conciencia. Revista de Neurología, 63(4), 176-185. [ Links ]

Toba, C., y Gil, R. (2009). Desde una organización tradicional-vertical hacia una organización basada en la horizontalidad y la participación. Una visión andragógico-gerencial. Visión Gerencial, (2), 398-414. [ Links ]

Ucrós, M., y Gamboa, T. (2010). Clima organizacional: discusión de diferentes enfoques teóricos. Visión Gerencial, 9(1), 179-190. [ Links ]

Uribe, A., Molina, J., Contreras, F., Barbosa, D., y Espinoza, J. (2013). Liderar Equipos de alto desempeño: un gran reto para las organizaciones actuales. Universidad & Empresa, 15(25), 53-71. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/1872/187229746004.pdf [ Links ]

Vergara, S. (2016). Construir inteligencia colectiva en la organización: Una nueva manera de entender y gestionar el clima laboral para alinear el bienestar de las personas con la gestión de la empresa. Santiago de Chile, Chile: Ediciones UC. [ Links ]

Vroom, V. H., y Yetton, P. W. (1973). Leadership and Decision-Making. Administrative Science Quarterly, 18(4), 556-558. [ Links ]

Yukl, G. (1990). Liderazgo gerencial: una revisión de la teoría y la investigación. Ciencia y sociedad, 15(4), 411-507. https://doi.org/10.22206/CYS.1990.V15I4.PP441-507 [ Links ]

Wofford, J. C. (1982). An integrative theory of leadership. Journal of management 8(1), 27-47. [ Links ]

Zenger, J., y Folkman, J. (2011). El líder extraordinario. Barcelona, España: Profit Editorial. [ Links ]

Received: January 17, 2022; Accepted: April 07, 2022

text in

text in