1. Introduction

Writing has traditionally been considered in academic contexts for gatekeeping or evaluation purposes, as passing or failing university courses frequently depends on reading and writing academic and disciplinary texts (Lillis, 2001; Thaiss & Myers-Zawacki, 2006). However, it is also considered as an element that promotes graduation in tertiary education (Fernandez Lamarra & Costa de Paula, 2011). In that context, many universities have incorporated academic writing and foreign language courses to their curricula to prepare students for the challenges of this heterogeneous society. However, foreign language learners present difficulty in achieving academic standards and a formal register while writing under traditional teaching methods (Hyland, 2006). This eclecticism in academic writing makes it necessary to describe literacy practices as they occur these days (Mcgrath & Kaufhold, 2016).

Writing in academic genres at university represents a challenge for these students as they were exposed to other literacy practices during their schooling, not related to the disciplinary communities (De Silva, 2015). In a longitudinal study, Zavala (2017) reported cases of two writers who feel their voice was not represented in the tasks assigned by teachers and curriculum. Both describe academic writing as a threat to their identity as this discourse does not convey natural communication. Street (2010) also described cases of alternative literacy practices in southern Asia that do not align with the formal, clear, precise, concrete and transparent features of academic discourse. Nevertheless, some initiatives have been conducted in tertiary education to integrate academic literacy to communicative approaches in foreign language instruction; which might have been perceived as epistemologically incompatible in academic writing contexts.

An informal style has never been considered as appropriate in academic contexts as it enhanced a more subjective interpretation of the writer towards a topic; risking its objectivity, sophistication and intelligibility. Notwithstanding situated approaches aiming to foster academic standards in second-language writers, current literacy practices are still regarded as informal as they do not fit the impersonal and sophisticated language of formal writing (Hyland & Jiang, 2017). However, an alternative notion of a continuum between formal and informal styles in academic writing is required (Hyland, 2007). In fact, Hyland and Jiang (2017) recognize that informality has entered oral and written discourse in recent years, following academic writing this tendency and becoming less formal.

In this regard, an informal use of a language attempts to build a more intimate relationship with readers, where assumptions about a shared context and more thorough background knowledge make communication possible. Therefore, texts that include an informal register as a first-person pronoun, colloquial language, verbal phrases, etc., should not be any more now considered as invalid samples of literacies. The following features of writing need to be considered to foster this skill: (1) writing as a collaborative activity, (2) the influence of the learning environment and the languages involved, and (3) the need of interaction and activities within a disciplinary discourse where the learners get familiarized with the genres and their purposes (McGrath & Kaufhold, 2016).

McGrath and Kaufhold (2016) describe that a commitment towards a ‘bottom-up approach’ is now observed at universities, allowing more pluralistic pedagogical choices. Strauss (2017) claims that traditional academic writing requirements do not serve the interests of the disciplines or of the students anymore, as they cannot make changes to promote proficient literacy in each vocational area. Kaufhold (2015) emphasizes the relevance of students’ involvement in the academic work as voluntary participation of them in her study provided evidence of their willingness and commitment towards the acquisition of academic writing, being active participants by incorporating their previous knowledge and learning experiences, in order to gain confidence as writers. Therefore, a more thorough insight towards literacy and academic writing is required to comprehend current practices occurring in the field of second language writing in university contexts.

The movement of Academic Literacies emerges as a response to legitimize actual literacy practices in the academic community (Lillis & Scott, 2015), trying to offer an alternative and comprehensive understanding of academic writing as a situated social practice, in which communication is the main target. Park (2013, p. 344) describes writing as “situated, social and political practice offering new writers in English an opportunity to find power and legitimacy in a new language,” in line with the movement of Academic Literacies, which describes actual written practices occurring worldwide. The main contribution of this approach towards writing is of a legitimating tool that writers and authors, independently of their cultural or linguistic background, use in academia to nurture themselves continuously to become part of such communities.

One of the major problems reported in foreign language instruction is to communicate accurately in the target language (L2). No full-immersion programmes are possible in non-native contexts, where learners rely on their mother tongue (L1) to communicate later in the target language. Doiz, Lasagabaster and Sierra (2013, p. 24) describe this linguistic phenomenon as translingualism, defining it as “the adoption of bilingual supportive scaffolding practices” towards language learning. From a Bakhtinian perspective, it refers to a strategy available to writers from diverse linguistic backgrounds that challenges limiting and oppressive discourses (Canagarajah, 2018). These practices occur more frequently when two or more different languages, varieties or people from different linguistic backgrounds interact with each other across time and space (Coronel-Molina & Samuelson, 2016). Translingualism tensions teaching and learning traditions which originate from a monolingual perspective. Translingualism also recognizes the multicultural and multilingual background of L2 learners and writers, challenging the desired linguistic homogeneity in L2 instruction (Matsuda, 2006).

Under the premise of writing as a means of new knowledge making throughout social interaction, ideas are never generated in isolation (Park, 2013). This implies a connection of the learners’ world knowledge, mostly represented in the L1, with the ideas and topics presented in the target language (L2) in the classroom. Despite the criticism to the use of L1 in the foreign language class, mainly by terms of L1 interference (May, 2013); some studies have been recently conducted to provide the benefits of traslanguaging, using different languages in pedagogical contexts (Blackledge & Creese, 2010; Canagarajah, 2013; Garcia & Wei, 2014). Furthermore, incorporating both languages in the classroom can increase learners’ willingness to use their entire linguistic repertoire more actively (Fu & Matuosh, 2015). Thus, using different languages to communicate reflects the reality of heterogeneous and multicultural societies, contributing to the integration of language practices worldwide (Garcia & Wei, 2014).

Considering the multilingual and multicultural backgrounds of today’s society, alternative approaches towards academic literacy are required to understand this phenomenon occurring both in first and second language writing in tertiary education. The latter is of utmost importance as student mobility has reshaped university contexts, allowing different languages to coexist. Nevertheless, academic literacy is still governed by monolingual paradigms under the hegemony of Written Standard English (Canagarajah, 2011). Translingualism emerges as an approach that challenges monoglossic language ideologies, informing second language writing. This perspective can also contribute to moving beyond the fallacy of the native speaker as the error-free language expert, empowering the non-native writer as an effective user (Phillipson, 1992).

This reconceptualization of academic literacy, however, leads to criticism in foreign language instruction and second language writing. Therefore, this literature review becomes relevant to support and frame alternative insights towards academic literacy with empirical evidence, empowering language teachers to make informed pedagogical decisions. Under translingual perspectives, writing might not anymore be considered a technology that restructures thought (Canagarajah, 2018) but also as developing alternate models in one language. The purpose of this revision is to inform the use of different languages, a concept known as translingualism, in academic writing preparation at tertiary level, reported in empirical research articles and organized systematically. Therefore, the following revision question guides this literature review:

What translingual practices are reported in empirical research articles as a contribution to the development of academic literacy at tertiary level?

On that account, a revision of empirical studies was conducted and is described in the methodology section, considering three main aspects found throughout these articles: theoretical foundations towards translingualism, translingual spaces in second language writing, pedagogical implications of translingualism and multimodality in translingual practices. The results of the revision and analysis of these articles are included in the third section of this assignment, followed by the discussion.

2. Methodology

Bibliographical research of articles in indexed journals was conducted in Web of Science and Scopus, considering the ten recent years, from 2010 to 2020, and data-driven sources. Although the topics partially relate to each other, keywords were essential to narrow the search process towards translanguaging in second language writing and academic literacy. Table 1 depicts the search criteria and the keywords used in this literature review.

Table 1 Keywords used in this literature review

| Search order | Keywords |

|---|---|

| 1 | “translingualism” OR “translanguaging” |

| 2 | “academic literacies” AND “translingualism” OR “translanguaging” |

| 3 | “academic writing” AND “translingualism” OR “translinguaging” |

| 4 | “second language writing” AND “translingual writing” |

| 5 | “academic literacies” AND “translingual writing” |

| 6 | “second language writing” AND “higher education” |

Source: Own elaboration based on the articles revised for this literature review.

Initially, 23.792 empirical articles were found. Therefore, a systematic revision of both titles and abstracts of each of the articles that refer specifically to translingual practices in academic writing in multilingual contexts was conducted, obtaining 622 papers. The inclusion criteria for the articles used in this literature review were: (1) open access, (2) publication date within the ten recent years, (3) written in English, (4) findings obtained through empirical research, and (5) papers referring to translingual practices informing foreign language instruction and academic literacies.

All articles referring to multilingualism, bilingualism, second language acquisition, genre pedagogies, as well as book reviews published in indexed journals, were excluded as their scope is not closely related to translingualism. Papers describing academic literacies and translingual practices at school level, regarding primary or secondary education; or to specific areas as translation, linguistics, sociology, were not considered in this literature review. Following these criteria, 26 articles informing translanguaging towards academic literacy practices resulted in the final revision.

Table 2 describes the 26 articles selected as the data-driven source for this literature review, organized upon the contribution of translingualism towards academic writing: Importance of L1 in the development of the writer’s identity, implications of translingualism in second language writing instruction and multimodality and digital translingual practices into writing. This classification was obtained after a brief revision of each article focusing on the empirical results reported and the authors cited in the discussion and bibliography; under the scope of the aforementioned revision question.

Table 2 Articles considered in the literature review

| Article | Methods | Sample | Aspect of contribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Adamson, J. & Coulson, D. (2015). Translanguaging in English academic writing preparation. International Journal of Pedagogies and Learning, 10(1), 24-37. | Qualitative - case study | 475 Japanese university students: questionnaire 271 students’ reports | Importance of L1 - identity development |

| 2. Albawardi, A. (2018). The translingual digital practices of Saudi females on WhatsApp. Discourse, Context and Media, 25, 68-77. | Qualitative | 220 WhatsApp chats of 130 Saudi university students studying English | Multimodality and digital translingual practices |

| 3. Anderson, J. (2017). Reimagining English language learners from a translingual perspective. ELT Journal, 72(1), 26-37. | Quantitative | 116 General English, Exam English and ESP learners | Implications of TL in L2 writing instruction |

| 4. Ashraf, H. (2018). Translingual practices and monoglot policy aspirations: a case study of Pakistan’s plurilingual classrooms. Current Issues in Language Planning, 19(1), 1-21. | Quantitative | 324 students’ responses recorded and transcribed | Importance of L1 - identity development |

| 5. Canagarajah, S. (2011). Codemeshing in Academic Writing: Identifying Teachable Strategies of Translanguaging. The Modern Language Journal, 95(3), 401-417. | Qualitative - ethnography | 1 graduate student in a teaching of secondlanguage writing course | Implications of TL in L2 writing instruction |

| 6. Canagarajah, S. (2018). Translingual Practice as Spatial Repertoires: Expanding the Paradigm beyond Structuralist Orientations. Applied Linguistics, 39(1), 31-54. | Qualitative | 24 Chinese scholars, 1 Korean and Turkish communicative practices | Implications of TL in L2 writing instruction |

| 7. Caruso, E. (2018). Translanguaging in higher education: Using several languages for the analysis of academic content in the teaching and learning process. CercleS, 8(1), 65-90. | Qualitative - Case study | 15 participants in a multilingual classroom at a university course in Portugal | Implications of TL in L2 writing instruction |

| 8. Cavazos, A. (2017). Translingual oral and written practices: Rhetorical resources in multilingual writers’ discourse. International Journal of Bilingualism, 21(4), 385-401. | Qualitative | Language practices of 3 scholars in academic genres. | Importance of L1 - identity development |

| 9. De Costa, P., Singh, J., Milu, E., Wang, X., Fraiberg, S. & Canagarajah, S. (2017). Pedagogizing Translingual Practice: Prospects and Possibilities. Research in the Teaching of English, 51(4), 464-473. | Qualitative | Autoethnography of teaching practices of six scholars in translingual pedagogy | Importance of L1 - identity development |

| 10.Flores, N. & Aneja, G. (2017). “Why Needs Hiding?” Translingual (Re) Orientations in TESOL Teacher Education. Research in the Teaching of English, 51(4), 441-463. | Qualitative | 36 university TESOL students’ projects (1st phase) | Importance of L1 - identity development |

| 11.Gevers, J. (2018). Translingualism revisited: Language difference and hybridity in L2 writing. Journal of Second Language Writing, 40, 73-83. | Qualitative | 10 students: focus groups and interviews (2nd phase) 2 first-year students of writing courses taught by the author | Implications of TL in L2 writing instruction |

| 12.Holdway, J. & Hitchcock, C. (2018). Exploring ideological becoming in professional development for teachers of multilingual learners: Perspectives on translanguaging in the classroom. Teaching and Teacher Education, 75, 60-70. | Qualitative - Action Research Case study | 114 teachers participating in a professional development programme through an online platform: 114 discussions and 114 summaries | Implications of TL in L2 writing instruction |

| 13.Hopkins, S., Zoghbor, W. & Hassall, PJ. (2020). The use of English and linguistic hybridity among Emirati millennials. World Englishes, 1-15. | Mixed-methods - Questionnaire, observations and classroom notes | 100 Emirati students studying an English writing course in Abu Dhabi university | Implications of TL in L2 writing instruction |

| 14.Kaufhold, K. (2018). Creating translanguaging spaces in students’ academic writing practices. Linguistics and Education, 45, 1-9. | Qualitative - case study | 2 participants in longitudinal case studies in Sweden | Importance of L1 - identity development |

| 15.Kiernan, J., Meier, J., & Wang, X. (2017). Translingual approaches to reading and writing. International Association for Research in L1 Education, 17, 1-18. | Qualitative | 9 students’ reflective memos | Implications of TL in L2 writing instruction |

| 16.Kim, S. (2018). “It was kind of a given that we were all multilingual”: Transnational youth identity work in digital translanguaging. Linguistics and Education, 43, 39-52. | Qualitative - case study | 1 participant: 3 interviews, 11 recorded informal conversations, 16 videos, identity map, literacy checklist and social media activities 9 compositions of 4th graders and 1 case study | Multimodality and digital translingual practices |

| 17.Kiramba, L. (2017). Translanguaging in the Writing of Emergent Multilinguals. International Multilingual Research Journal, 11(2), 115-130. | Qualitative | 5 students in an EMI programme in Business Studies at Swedish university | Importance of L1 - identity development |

| 18.Kuteeva, M. (2019). Revisiting the ‘E’ in EMI students’ perceptions of standard English, lingua franca and translingual practices. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 23(3), 287-300. | Qualitative | 3 Chinese youths at University of London: interviews, observations and recordings of social interaction | Importance of L1 - identity development |

| 19.Wei, L. (2011). Moment Analysis and translanguagingspace: Discursive construction of identities by multilingual Chinese youth in Britain. Journal ofPragmatics, 43, 1222-1235. | Qualitative | Corpus of ordinary English utterances between Chinese users of English | Importance of L1 - identity development |

| 20.Wei, L. (2018). Translanguaging as a Practical Theory of Language. Applied Linguistics, 39(1), 9-30. | Qualitative | Exchange between a Chinese-Singaporean and a friend, 11 learners of Chinese | Importance of L1 - identity development |

| 21.Wei, L. & Ho, W. (2018). Learning Language Sans Frontiers: A Translanguaging View. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 38, 33-59. | Qualitative | Transcript of screen recording of 2 learners | Multimodality and digital translingual practices |

| 22.McIntosh, K., Connor, U. & Gokpinar-Shelton, E. (2017). What intercultural rhetoric can bring to EAP/ ESP writing studies in an English as a lingua franca world. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 29(1), 12-20. | Qualitative - case study | Post-graduate science and engineering students in a grant proposalwriting module | Importance of L1 - identity development |

| 23.Mori, J. & Sanuth, K. (2018). Navigating between a monolingual utopia and translingual realities: Experiences of American learners of Yorùbá as an Additional Language. Applied Linguistics, 39(1), 78-98. | Qualitative | 6 graduate and 5 undergraduate Nigerian students: fieldnotes and interviews | Importance of L1 - identity development |

| 24.Motlhaka, H. & Makalela, L. (2016). Translanguaging in an academic writing class: Implications for a dialogic pedagogy. Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies, 34(3), 251-260. | Qualitative - case study | 8 first-year students of the Curriculum Design Model at a urban university in S. Africa | Implications of TL in L2 writing instruction |

| 25.Wagner, J. (2018). Multilingual and Multimodal Interactions. Applied Linguistics, 39(1), 99-107. | Qualitative - Ethnomethodology and Conversation Analysis | Conversation between 3 non-native English speakers using English to communicate | Multimodality and digital translingual practices |

| 26.Yanguas, I. (2019). L1 vs L2 synchronous text-based interaction in computer-mediated L2 writing. System, 88, 1-11. | Quantitative | 85 intermediate students of Spanish in four dyadic writing groups at a US college | Implications of TL in L2 writing instruction |

3. Results

To begin with, a synthesis of bibliometric descriptors is provided, considering year and country of publication, the journal publishing the articles and the methodological design described. The main findings of the research articles part of this literature review follow, suggesting translingual practices as an evidence of developing academic literacies in second language contexts, specifically regarding writing instruction at university level.

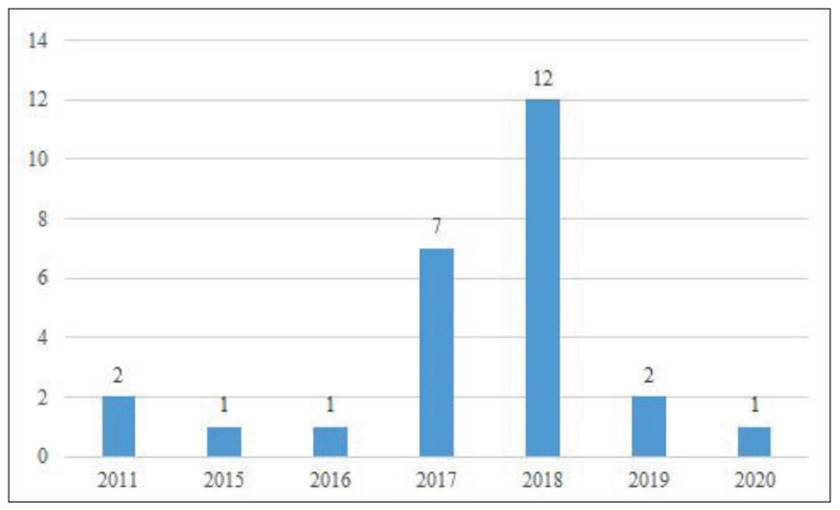

Regarding the year of publication, empirical articles conducted between the years 2010 and 2020 were considered in the initial stage of this literature review. However, the first research reporting translingual practices in second language writing at tertiary level was published in 2011. A total of 26 papers were identified within this period, outnumbering years 2017 and 2018, with seven (27%) and twelve (46%) published articles respectively. Figure 1 illustrates the number of articles in each year of publication.

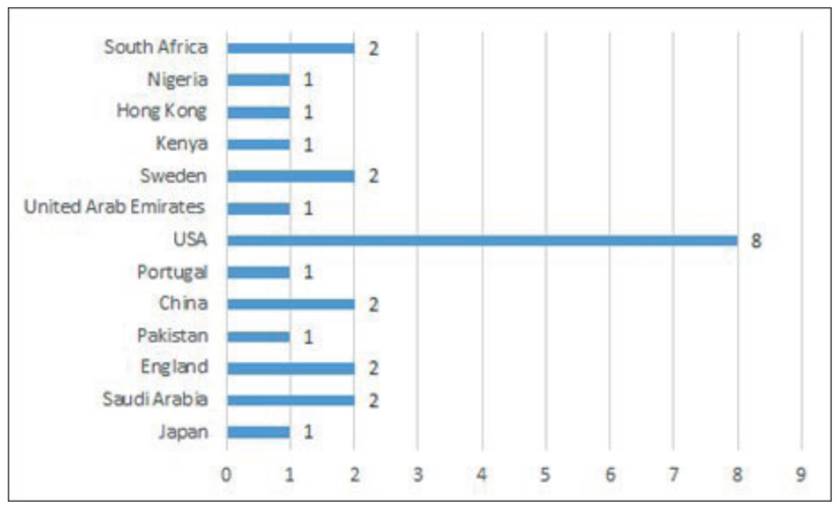

Referring to the geographical distribution of these research articles, two variables were considered: the country where the research was conducted and the country of the publishing journal. Regarding the former, a democratic geographic distribution is observed worldwide. Eight articles (32%) report research conducted in Asia, eight (32%) in America, five (20%) in Europe and four (16%) in African countries. Besides the US, South Africa, Sweden, China, England and Saudi Arabia outline with two articles each. Figure 2 organizes the geographical distribution in terms of the country where the research was conducted.

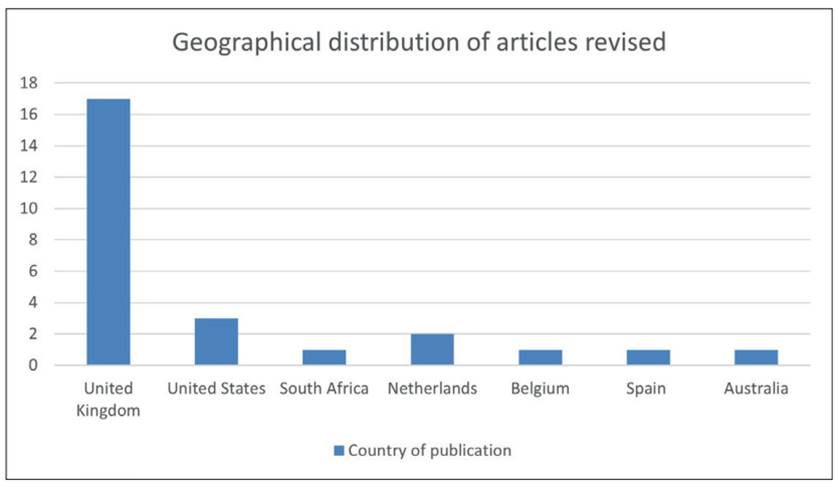

On the other hand, British indexed journals concentrate two-thirds of the research articles (65%). US journals published 12% of these papers (N=3), followed by the Netherlands with 8% (N=2). Belgian, South-African, Spanish and Australian journals had each 4% of the articles each (N=1). Figure 3 depicts the geographical distribution in terms of the country of publication, whereas the journals where these research articles were published are described in Table 3.

Table 3 Journals and countries of publication of articles of this literature review

| Journal | Country of publication | N° articles |

|---|---|---|

| African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies | South Africa | 1 |

| Annual Review of Applied Linguistics | United Kingdom | 1 |

| Applied Linguistics | United Kingdom | 4 |

| Cercles | Spain | 1 |

| Current Issues in Language Planning | United Kingdom | 1 |

| Discourse, Context and Media | Netherlands | 1 |

| ELT Journal | United Kingdom | 1 |

| International Association for Research in L1 Education | Belgium | 1 |

| International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism | United Kingdom | 1 |

| International Journal of Bilingualism | United Kingdom | 1 |

| International Journal of Pedagogies and Learning | Australia | 1 |

| International Multilingual Research Journal | United Kingdom | 1 |

| Journal of English for Academic Purposes | United Kingdom | 1 |

| Journal of Pragmatics | Netherlands | 1 |

| Journal of Second Language Writing | United Kingdom | 1 |

| Linguistics and Education | United Kingdom | 2 |

| Research in the Teaching of English | United States | 2 |

| System | United Kingdom | 1 |

| Teaching and Teacher Education | United Kingdom | 1 |

| The Modern Language Journal | United States | 1 |

| World Englishes | United Kingdom | 1 |

Source: Own elaboration based on the articles revised for this literature review.

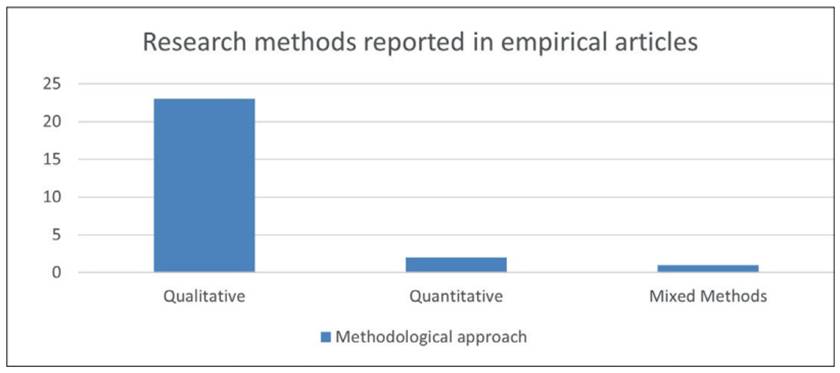

Regarding research methods involved in each of the articles part of this revision, 88% (N=23) informed qualitative procedures in their methodological sections, whereas two articles (8%) were conducted under quantitative methods. Only one paper (4%) reported mixed-methods research, combining both qualitative and quantitative approaches. Figure 4 provides an overview of the research methods considered in this literature review.

Finally, from the 26 articles considered in this literature revision, one referred to ontological and theoretical reflections towards translingualism, from a poststructuralist perspective (Canagarajah, 2018). 46% of the articles (12) focused on the importance of L1 in the development of the writer’s identity in academic contexts whereas 38% of them (10) discussed the implications of translingualism in second language writing instruction. Finally, four papers (16%) incorporated multimodality and digital translingual practices into writing. This section describes the findings from this literature review to describe translingual writing as an insight to comprehend writers’ entire linguistic repertoire.

3.1. Importance of L1 in the development of the writer’s identity

Translingual practices might tension the boundaries and conventions of academic literacy, as it challenges and resists the hegemony of Written Standard English (WSE). Their relation to literacy has led controversy, mostly in academic contexts, as they are still informed by a monolingual paradigm that emerged from a dominant native-speaker ideology that values efficiency in communication, as well as focuses on form and grammar over social practices (Gevers, 2018). Under multilingual and translingual perspectives, writing might not anymore be understood as a technology that restructures thought (Canagarajah, 2018) but as developing alternate models in one language. This reconceptualization of writing, however, leads to criticism in foreign language instruction and in second language writing.

According to Canagarajah (2011), writing implies the active involvement of the author and the target readers in the process itself. Kiernan, Meier and Wang (2017) argue that writing is an essential skill to practice in order to engage in deeper and more meaningful learning, since it “stabilises discourse and practice, developing agency.” Kaufhold (2018, p. 7) describes the simultaneous use of L1 and L2 as a means to develop fluency in writing. “Not only does a multilingual orientation more accurately reflect the linguistic reality within the academic community, it is also consistent with ‘connected’ online culture” (Adamson & Coulson, 2015, p. 27). In fact, Kuteeva (2019) describes a case of a US student in a Swedish university switching to British linguistic variety only in academic writing contexts. Multilingual students could benefit from their knowledge and experience of academic writing across language codes, focusing both on the construction of the writer’s identity and socio-political constraints to multilingual writing (Canagarajah, 2011).

Although traditional foreign language instruction promotes communication exclusively in the target language, some pedagogical practices allow the use of L1 in academic writing. For instance, Mori and Sanuth (2018) report US participants having difficulty in learning Yorùbá as a second language in Africa. The desired monolingual utopia, despite being in a country where Yorùbá was spoken by majority of people, was not possible due to translingual realities. Ashraf (2018) reports a continuum between English and Urdu in Pakistan, recognizing the presence of more than one language in communication and raising language awareness in formal educational settings. Emirati university students use both Arabic and English when performing university tasks, with predominance of the latter due to its academic status in the UAE context (Hopkyns, Zoghbor & Hassall, 2020). Kiramba (2017) considers that translingual practices transgress monolingual habitus, especially in countries where the mother tongue is neglected in favour of the colonization language, as the cases previously described.

Translingual practices do not only occur in environments where people cannot communicate in their mother tongue. Translingualism is also reported in developed countries as England, where Wei (2011) describes the experience of three Chinese students in London. They communicated both in English and Chinese depicting confidence in their own multilingualism, despite the monolingual ideologies predominant in today’s London. Kaufhold (2018) reports experiences with language, Spracherleben, of two Swedish students writing their dissertations in English. Despite studying in their home country, they declared negotiating and developing their repertoires in academic writing in both languages. Interestingly, one participant claims ownership of the foreign language as English assists her in developing her identity as a scholar. Adamson and Coulson (2015) narrate the experience of 495 Japanese students in bilingual university contexts. Despite the predominance of English as having more prestige for business and academic purposes, these students declare using their L1 for in-class and writing purposes.

To conclude, translanguaging as a creative, transformational and collaborative space can be a fruitful pedagogical metaphor for students to explore; assisting them to develop a metalanguage and an awareness of multicultural repertoire instead of cultural assimilation of the target language. The latter can assist them in developing their identities as writers in academic contexts, either in L1 or L2, contributing to the meaning-making goal. However, second language writers need to feel confident to negotiate ideologies, meaning and language perspectives in order to achieve their communicative purpose. Therefore, L1 should not be considered a detriment anymore in foreign language learning as it is a mirror of language use in a multicultural society.

3.2. Implications of translingualism in second-language writing instruction

Monolingual perspectives based on colonialism and monoglossic language beliefs remain as the guiding framework in foreign language instruction (Kiernan, Meier & Wang, 2017). Native speaker ideologies continue influencing language teaching marginalising non-native speakers as language teachers and maintaining the privileges of the former in job positions, curricular resources and language assessments (Holdway & Hitchcock, 2018). However, translingualism provides a framework to challenge these ideologies and a new understanding of language in multicultural and multilinguistic contexts (Caruso, 2018). Under a translingual approach, language development is no longer described as attainment of “native-like” proficiency, but as choosing strategies for communication in ways that reflect bi/multilingual identities and accommodate their interlocutors, informing their repertoire (Anderson, 2017).

However, translingual practices are not homogeneous as they might vary depending on the language user profile. Anderson (2017) suggests a translingual continuum to understand language practices in the multicultural classroom settings, providing practical suggestions for language teachers, going from monolingual to highly translingual. In his research, 19.8% of the participants considered to be mainly monolingual, as they might be speaking English only in their future professional context; for instance, in Hong Kong or the United Kingdom. Regarding translingualism, 47.4% referred to themselves as partly translingual as some might be using English, sometimes monolingually and sometimes more translingually; whereas 20.7% identified as highly translingual. These results depict that nowadays, more language users identify as translingual, instead of monolingual.

Non-native language teachers can find in translingual practices support to develop more positive conceptualisations of their identities. Translingualism can also provide a framework to develop pedagogical approaches for students from multilingual backgrounds (Flores & Aneja, 2017; Holdway & Hitchcock, 2018). Motlhaka and Makalela (2016), for instance, reported learners using both English and Sesotho to move strategically between different rhetorical conventions in their academic writing stages. Translingual practices also reshape the content of teacher education, breaking down the binary oppositions that characterize this field. This means reimagining the language classroom as a translingual community, as in Anderson’s study (2017) where the participants identified themselves as translingual practitioners, avoiding dichotomies between native and non-native speakers. The latter redefines the authenticity of a language speaker (Gevers, 2018).

Translingualism does not entail doing and saying whatever speakers want, but a negotiation of all communicative interactions and shifts of language that students must acquire by following correct rules of grammar, and towards treating language as a malleable tool to develop unique rhetoric styles (Caruso, 2018). For instance, her students had the freedom of communicating in English, French, Portuguese, Italian or Spanish, but using an appropriate register and accurately. Translanguaging broadens the understanding of codeswitching as it refers to a more flexible use of resources from more than one language within a single system, transcending traditional understandings of separate languages. The notion of languages as separate, largely immutable entities is then challenged, including multimodal resources to communicate. Translingual practices involve negotiating code-choice where communication moves along this continuum, depending on activity, outcome and interlocutors (Caruso, 2018).

Communicative competence comes from monolingual perspectives, whereas translingual competence recognizes that code choice might be negotiable and fluid, when appropriate; adjusting to the multilingual multimodal terrain of the communicative act (Garcia y Klelfgen, 2009). The latter is evidenced nowadays in online and virtual communities, becoming necessary to integrate the concept of “semiotic competence” within translingualism. Technology has restructured academic genres within scholar communities, where emails replaced formal letters and instant messaging memorandums. For that reason, the role multimodality plays in academic writing nowadays and how translingualism mediates literacy practices is described in the last section.

3.3. Multimodality and digital translingual practices in writing

Translanguaging, as a theory of language, has reshaped academic literacy incorporating the use of technology and digital media into writing practices. Wei and Ho (2018), as well as Wagner (2018), describe this phenomenon as a transdisciplinary research perspective. Human communication has always been multimodal as people interact through textual, aural, linguistic, spatial and visual resources. Interconnections between language and other cognitive systems make communication a multimodal phenomenon (Kim, 2018). Albawardi (2018) reports Saudi women communicating using multimodal codes in ‘Arabish,’ an Arabicized English, through WhatsApp. Such digital practices are considered by the author as translingual, where participants engage in fluid language interaction.

Although languaging might be considered multimodal, our understanding of language as a semiotic system is based on Indo-European languages and language studied as speech or text (Wagner, 2018). Therefore, language was initially described, and is understood until now, as an arbitrary of symbols and rules, where the resemblance between form and meaning is the norm. However, gesture does influence thinking and speaking, converting languaging into a multimodal phenomenon (Albawardi, 2018). Image, writing, layout, speech and moving images are examples of different modes, described by Wei and Ho (2018) as a “socially and culturally shaped resource for meaning-making.” Moreover, Kim (2018) presents how language and images converge as one code when communicating is the purpose. Albawardi (2018) also suggests that both codes seem necessary as an attempt not to give up cultural identities in a globalized community.

Translanguaging instinct fosters to go beyond the linguistic norms to achieve effective communication, including the multisensory and multimodal process of language learning and language use (Albawardi, 2018; Kim, 2018). Translanguaging instinct has also implications for language learning, as the acquisition of first and second language in early childhood and adulthood differ in cognitive, semiotic systems that affect linguistic semiosis. Therefore, as people become more involved in complex communicative tasks and demanding environments, they tend to combine and exploit a variety of resources to foster social interactions. This innate capacity of exploiting resources is enhanced with experience, becoming more developed through metalinguistic awareness in adult learners. The multisensory, multimodal and multilingual nature of human learning and interaction is at the centre of translanguaging Instinct.

4. Discussion

As previously suggested, translingual practices could be described as instances where users can integrate social spaces and linguistic codes that have been traditionally separated through practices in different places due to monolingual paradigms informing academic literacy (Wei, 2011). These instances make the language user go beyond linguistic structures, cognitive and semiotic systems and modalities, as well as bringing together different dimensions of the learners’ personal history, experience and environment, their attitude, belief and ideology, and their cognitive and physical capacity (p. 1223). Furthermore, variety and continuity of interactions of people from diverse backgrounds using current technology enhance the construction and reconstruction of social identities, constantly modified through language. However, Wei (2018, p. 106) avoids generalizing translingualism as a theory, reporting it as “a resource to be chosen. In fact, he suggests participants’ responsibility for the language used for communication.

From a translingual perspective, not only can learners integrate their knowledge from L1 to L2 easily, like anxiety and lack of confidence in the target language decrease, but these literacy practices, of a language course exercise, can be transferred to real situations and the curriculum (Adamson & Coulson, 2015). This aspect is crucial while developing literacy skills at tertiary level, where autonomous and long-life learning is required. Regarding the use of different languages in writing, this reflects our current multicultural society where we might rely on our mother tongue in the brainstorming, planning, organization or editing stages (Motlhaka & Makalela, 2016). Canagarajah (2011) describes four strategies that multilingual learners use while translanguaging in academic writing tasks: (1) recontextualization, (2) voice, (3) interactional and (4) textualization. In general terms, translanguaging prioritizes the communicative nature of language over focusing on form. Both the background and learning experience of these learners influence their writing process. However, they also take ownership of the target language and invite the reader to renegotiate the meaning and how the messages are being delivered.

Translanguaging also brings a variety of linguistic resources to academic writing in terms of meaning-making in academia (Cavazos, 2017). Switching languages occurs naturally and is a strategy that multilingual students employ intuitively (Canagarajah, 2018; Cavazos, 2017; Cumming, 2006; Kiramba, 2017). In this case, learners can display their knowledge about a specific genre and transfer it to similar genres in different language codes, provided lexico-grammatical resources are available. To achieve this, the register and the written genre need to be familiar to the audience or readers in the different languages, and accepted by these communities. For instance, research articles and thesis are regarded by Kaufhold (2018) as a pedagogic genre (Johns & Swales, 2002), whose conventions are carefully observed by the academic community, independently of language codes. Not only does translingualism make silent voices heard through writing, but it questions the role of local languages promoting permeability across languages for multilinguals.

Nevertheless, whereas advanced L2 writers may have a proficient level in L2 that allows them to experiment with translingual practices without major problems, low-level students might require more opportunities to develop proficiency in the target language (Gevers, 2018). Transference of orality-based discourse to writing could assist learners in expanding their expressive range and challenge restrictive conventions through creative innovation. However, it can also hinder their developing of proficiency in the target language and a formal register, especially in environments where the latter plays a crucial role. Therefore, L2 writing teachers need to consider the literacies expected of multilingual students in academic and professional communities in order to evaluate to what degree L2 students might benefit from incorporating non-standard language patterns into their writing (Gevers, 2018; Kiramba, 2017).

Developing multilingual awareness in language teachers might provide them with tools to address their students’ multilingualism in the L2 classroom; legitimizing both language proficiency and cultural backgrounds of non-native teachers (Flores & Aneja, 2017). Language diversity should then be seen as a resource that can facilitate more effective communication (Mori & Sanuth, 2018). Canagarajah (2013) identified for translingual macrostrategies in second-language writing: (1) invoicing, (2) recontextualization, (3) interactional strategies, and (4) entextualization; which provided these learners with opportunities to negotiate meanings by challenging the dominant monoglossic language ideologies. Translingualism require moving alongside this continuum described in order to promote interaction among speakers; adapting to the context involved, by means of activity, outcome and interlocutors. This insight is referred to as a starting point to empower non-native English-speaking teachers in foreign language instruction.

5. Conclusions

The articles revised for this systematic literature review lead to conclude that there is limited research informing translingual practices in academic or professional writing contexts, even though different projects have been conducted in translingualism at school level and in teacher training programmes. In fact, 0,96% of the 23.792 papers describing translingual practices published in indexed journals refer to academic literacy at university level. Most articles referring to translanguaging describe classroom experiences where different linguistic codes coexist, mostly based on class observation in secondary education. However, this literature review suggests that more research needs to be conducted for a thorough comprehension of this linguistic phenomenon, occurring worldwide due to globalization and technology.

Current academic contexts privilege native-like monolingual paradigms, which is evidenced in foreign language instruction where teachers require learners to imitate native speakers of the target language. Besides influencing L2 teaching and learning processes, this notion excludes actual social practices where different languages interact in different media like social networking. Not only does this monoglossic ideology exclude multilingual practices among speakers, who are described as non-proficient users of the target language; but it hinders language development of people aiming to communicate in a variety of codes as academic literacy. The experiences reported in the research articles reviewed in this study suggest that translingual literacy practices promote creative and collaborative writing, as well as provide an opportunity to develop written production integrating their linguistic repertoire, which is often constructed in more than one language.

Moreover, translingualism contributes to developing transversal strategies that enhance interaction among speakers from a diversity of multicultural backgrounds. The latter has an impact on the communicative competences of language learners, who use a variety of linguistic resources available in different languages, not due to incomplete development of the target language but to informed choices between different codes. Translanguaging, therefore, has a positive impact on the development of the identities of language learners, who recognize themselves as translingual writers with voice in the L2, claiming its ownership. The idea of a continuum proposed in this literature review challenges academic writing tradition, requiring a reconceptualization of literacy practices in terms of style, register, use of language, genres and media; where translingualism aims to describe actual communication patterns.

Finally, some limitations emerge from this literature review if considering writing as a process instead of a final product, mostly regarding the drafts where translingual practices occur. Most studies in second language writing either focus on the linguistic description of finished written assignments or suggest pedagogic models based on monolingual paradigms, where the learner needs to master a skill using unfamiliar linguistic codes. A translingual insight might also lead to rethink pedagogic and teacher-training practices, as learners might be able to use their whole linguistic repertoire without being labelled as non-proficient users, especially in a globalized society where a variety of cultures coexist and interact. Future research needs to address writing as a process to evidence translingual practices in written communication, mostly as temporary drafts in pre-writing stages. Technology also tensions the traditional notion of L2 academic literacy, where multimodal texts outline informed choices of using different codes once multilingual awareness is achieved. This multimodality could portray translingual literacies in second language writing, providing a new insight that reflects current academic practices where different languages coexist for meaning-making and communication.