Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Science

Print version ISSN 2077-1886

Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Science vol.15 no.28 Lima June 2010

Determinants of Strategic Risk Management in Emerging Markets Supply Chains: The Case of Mexico

Determinantes del manejo de riesgo estratégico en las cadenas de suministro en mercados emergentes: el caso de México

Walfried Lassar1; Jerry Haar2; Raúl Montalvo3; Leslie Hulser4

1. Walfried Lassar, Ph.D. Ryder Professor and Director, Ryder Center for Supply Chain Management, Florida International University, USA., University of Southern California. <walfried.lassar@fiu.edu>.

2. Jerry Haar, Ph.D. Professor of Management and International Business, Florida International University, USA. Columbia University. <jerry.haar@fiu.edu>.

3. Raúl Montalvo, Ph.D. Professor of Economics, Tec of Monterrey, Guadalajara Campus, Mexico. University of Essex. <rmontalvo@itesm.mx>.

4. Leslie Hulser, Research Associate, Ryder Center for Supply Chain Management, Florida International University, USA. MBA, Florida International University. <lahulser@courtneysolutions.com>.

Abstract

Risk mitigation in global supply chains has grown in importance in recent years, in tandem with globalization and both the commercial and security threats faced by firms both large and small. This study hypothesizes that a firms ability to manage risk strategyand therefore support its competitivenessis determined by a symbiotic triad of factors: the resources it utilizes; network systems; and performance criteria it employs. The study, comprising 24 in-depth interviews with electronics and IT firms, examines resource utilization through the Resource-Based View (RBV), assesses firms proclivity to engage in networks for risk mitigation and competitiveness; and highlights the importance of performance evaluation as a critically important component in supply chain management. Findings reveal that both buyers and suppliers believe that the symbiotic triad can provide them with a competitive advantage in addition to improving operational efficiency, effectiveness and quality. Future research should also extend this pilot investigation to other countries and industries, and utilize a larger sample of firms for quantitative as well as qualitative assessment.

Keywords: Risk management, emerging markets, Supply Chain Management, IT.

Resumen

La disminución del riesgo en las cadenas de suministro globales ha crecido en importancia en los últimos tiempos, junto con la globalización, así como las amenazas comerciales y de seguridad que las empresas, tanto grandes como pequeñas, enfrentan. Este estudio plantea la hipótesis de que la habilidad de una firma para manejar la estrategia de riesgo –y así sostener su competitividad- está determinada por una triada simbiótica de factores: los recursos que utiliza; los sistemas de interconexión; y el criterio de rendimiento que emplea. Este estudio, que comprende 24 entrevistas a fondo con empresas IT y electrónicas, examina el uso de recursos a través del Resource-Based View (RBV), evalúa la proclividad de la empresa de interconectarse para mantener su competitividad y mitigar el riesgo; y resalta la importancia de evaluar el rendimiento como un componente crítico en la administración de la cadena de suministro (supply chain management). Los resultados revelan que tanto los compradores como los proveedores creen que la triada simbiótica les puede proporcionar una ventaja competitiva además de mejorar su eficiencia operacional, efectividad y calidad. En tal sentido, las investigaciones futuras deberán extender este estudio piloto a otros países e industrias, y utilizar una muestra más amplia de firmas tanto para la evaluación cuantitativa como cualitativa.

Palabras clave: Manejo de riesgo, mercados emergentes, manejo de cadenas de suministro, TI.

INTRODUCTION

Risk mitigation in global supply chains has grown in importance in recent years, in tandem with globalization and both the commercial and security threats faced by firms both large and small. Among emerging markets, where such challenges are especially acute, Mexico stands out. Both Asian competition and internal security issues (namely drug cartels) have ratcheted up risk indices in that nation to higher than average levels. Mexicos offshore manufacturing sector has been especially hard hit (United States General Accounting Office, 2003). Many firms have left the region and many more are struggling to keep their heads above water. For example, after experiencing rapid growth in the 1990s, a significant decline in the maquiladoras industry led to a 20% reduction in production and a loss of 290,000 jobs by 2002. The industry continues to face risks of increasing competition from Asia and the strong economic ties to the U.S. (United States General Accounting Office, 2003).Strikingly, there has been scant reporting on the challenges facing Mexican enterprises.

Unquestionably, the intense competition in the global environment will continue; and as a consequence, firms will need to continuously rethink, reorganize, restructure, and reassess their capabilities and operationsMexicos maquiladoras and their suppliers are no different (Sánchez et al., 2002). Mexican firms will need to integrate efficient management practices into their operations to remain competitive in the current economy (Arroyo et al., 2006). The use of 3PL providers by Mexican firms continues to be less than that of European or U.S. firms, with reasons being the lack of availability of quality providers (Arroyo et al., 2006). Therefore, delivering products and services with efficiency and effectiveness along with ensuring quality throughout the process will prove challenging to most companies. As Ketchen and Hult (2007) point out, the real competition will not be among companies but among supply chains. Firms must view their entire production system in order to determine their overall comparative advantage and make decisions about activities in their value chain (Haytko & Kent, 2007; Porter, 1990). This is especially true in the case of Mexico where both production sharing operations and strong internal demand for both locally made and imported products are driving supply chains to optimize performance (Ordóñez, 2005; Hausman & Haytko, 2004; Unger, 2003).The supply chain challenges of the industry were highlighted in 1997 by Mexico having the highest cost of logistics to GDP compared to any other country. While low wages made this area attractive to manufacturers, cross-border logistics continues to be a risk to the industry (Haytko & Kent, 2007).

The researchers submit that risk management strategies in supply chains will be determined by a symbiotic triad of factors: the resources it utilizes; network systems; and performance criteria it employs. Resource utilization (the Resource-based View) offers strong explanatory power (Ketchen & Hult, 2007); the need to articulate with and integrate the various nodes within the supply chain (e.g., other suppliers, buyers, customers, facilitating organizations) (Wu et al., 2006; Sahin & Robinson, 2002) also plays a major role; and performance systems (management and evaluation) are critical determinants as well. In the 2006 Understanding Latin Americas supply chain risks survey by McKinsey, regulatory risks were cited as one of the top challenges to supply chain management for Latin American executives. Meanwhile, 49% of those executives felt their companies did not have effective procedures in place for mitigating supply chain risk (Krishnan, Parente, & Shulman, 2006).

In fact, how well firms and suppliers mobilize and manage resources, networks and performance are of no less importancein fact, perhaps even more sothan government policies, exchange rates, labor laws, and external competition from the Far East (Ford et al., 1998; Soler & López, 2005; Tan et al., 1999; Power, Sohal, & Rahman, 2001; Harland, 1996; Capó-Vicedo, Tomás-Miquel & Expósito-Langa, 2007).

For the last twenty years, the maquiladora (offshore production sharing) industry has formed the backbone of Mexicos manufacturing sector. Employing over 1.2 million workers, this sector accounts for more than a third of Mexican manufacturing jobs and is a major supporter of both U.S. and Mexican border cities (Cañas & Gilmer, 2009). While removed from endogenous industrial development, it nonetheless has been a significant generator of exports, employment and tax revenue. Investigating firm-level behavior from a strategic risk management framework not only adds to the knowledge base of research on maquiladoras in Mexico, but provides guidance and practical advice to supply chain participants, including firms, suppliers, and customers (Barratt & Oke, 2007; Krishnan, Parente, & Shulman, 2007).

CONCEPTUALIZATION

Conceptualizing strategic risk management in supply chains in emerging markets leads one to consider, most importantly, the resources an enterprise has or may be able to mobilize to mitigate risk on a continuous basis; networks and their linkage internally and externally to share both tacit and explicit knowledge and other information; and performance systems and their management, as they relate to individuals, groups, and business units.

The Resource-based View

The resource-based view is an economics-based, theoretical tool that analyzes, presents and predicts how firms attain a sustainable competitive advantage. It argues that the application of a bundle of resources at the firms disposition, or within its grasp, can achieve this goal, providing the resources are heterogeneous in nature and not mobile (Barney, 1991; Grant, 1991; Wernerfelt, 1984; Peteraf, 1993). The seminal work of Barney (1991) and Peteraf (1993) on the foundation of RBV yields four principal resources that a firm must possess to achieve a sustainable competitive advantage. The acronym is VRIN: valuable, rare, imperfectly imitable, and non-substitutable. As Dierickx and Cool (1989) assert, these resources1 must be considered/mobilized collectively for the firm to achieve a sustainable competitive advantage.

The RBV applied to supply chains has received limited attention in management research, despite its strong explanatory power in best value supply chains those that can be inimitable competitive weapons (Ketchen & Hult, 2007; Holcomb & Hitt, 2007; Miles & Snow 2007). Given the interdependencies that exist between suppliers and their customers (Watts & Hahn, 1993) and the very nature of supply chain interaction as a form of inter-firm relationships (Carter & Ellram, 1994), the RBV can be utilized to explain, enhance, and preserve the key supplier relationships throughout the chain (firm-supplier-customer), and to evaluate performance and maximize the benefits from the relationship (Rungtusanatham, Salvador, Forza, & Choi, 2003). Capabilities that are rare to come by, not imitable, and not substitutable in supply chains (e.g. Cemex in cement delivery; Amazon in books; Intel in chips) facilitate the management of the flow and quality of input and output, increase operational performance and strengthen the synergistic relationship of the supply chain overall.

Linking Networks

Resource acquisition, no matter how judicious and efficient, cannot increase supply chain competitiveness unless the resources are integrated into the relationships conducted and maintained throughout the chain. Firms and their suppliers must cooperate between themselves, as well as with their own respective partners. Networks create paths for firms to collect information, fend off competition, and coordinate pricing or policies (Wasserman & Faust, 1994). Reciprocity in such cooperative relationships is vital (Oliver, 1990) and key to the development of new resources (Håakansson & Ford, 2002). These collective efforts can yield positive gains within the supply chain that firms acting on their own might not be able to achieve (Håakansson & Snehota, 1995; Harland & Knight, 2001). A network approach (Thorelli, 1986) is grounded in the communications linkages among various parties in the supply chain-suppliers vis-à-vis their clients and customers, as well as within their respective organizations. While various facets of the network relations are standard or pro forma, factors such as trust and chemistry move the relationships to customized ones. Dynamic at its core---moving, changingthe links between firms in a network encompass what Johanson and Mattsson (1987) categorize as two types of interaction: exchange processes (such as products, services, information) and adaptation processes (administrative, logistics, technical, personal). Relationships within supply chains may be characterized as strong and weak; tightly coupled firms comprising the former, loosely configured ones the latter (Granovetter, 1973). Best value supply chains, according to Ketchen and Hult (2007), comprise a blend of strong and weak ties to maintain reliability and flexibility and maximize supply chain performance. In essence, though, the resources based in, and harnessed by, suppliers and their customers to ensure mutually satisfying and soundly functioning networks are dependent upon power and trustparticular the latter (Uzzi, 1997).

Performance Issues

Performance metrics help firms determine if they are meeting their customer expectations and strategic goals by providing direct information and feedback from supply chain processes (Chan, 2003). Effectively managed supply chains need clear, well-defined performance measures to remain competitive. Focal firms in Mexico often consider items other than cost when selecting 3PL providers such as quality and customer service (Arroyo et al., 2006) further highlighting the importance of monitoring performance. The myriad of choices of performance metrics covering cost, quality, timeliness, social responsibility, customer service and productivity, among others, makes the decision of what items to monitor complicated for firms. Extensive research has determined metrics for measuring supply chain performance (Mentzer et al., 2001a; Krause et al., 2000). Individual firms must determine what metrics are appropriate for their organization to avoid overwhelming managers.

In 2007, Bhagwat and Sharma determined that a systematic framework for performance measures, such as a balanced scorecard approach based on identified goals will benefit the firms management. Additionally, proper use and measurement of appropriate actions can help to identify problems and opportunities within the supply chain (Bhagwat & Sharma, 2007). Knowledge is essential for management to assess the supply chain and to determine how individual components are impacting overall firm performance allowing them to focus on the most beneficial activities (Chow et al., 2008). Performance measures are also increasingly important in minimizing risk in global supply chains. The use of performance requirements in contracts, combined with appropriate incentives, can promote improved delivery and performance along with providing feedback to improve the supply chain, thereby lowering overall risk for firms (Cheng & Kam, 2008).

The three factorsresources, networks, and performance--and the relationship among them are the subject of our empirical assessment of competitiveness in Mexicos supply chains.

METHODOLOGY

The grounded theory methodology was chosen to explore the symbiotic triad of resources, networks, and performance. According to Strauss and Corbin (1998), the grounded theory allows the investigation of concepts and relationships collected in qualitative data to be organized into a theoretical theme. Therefore, this theory allows for multiple investigations into different relationships to assist in the analysis of the multi-variant research question.

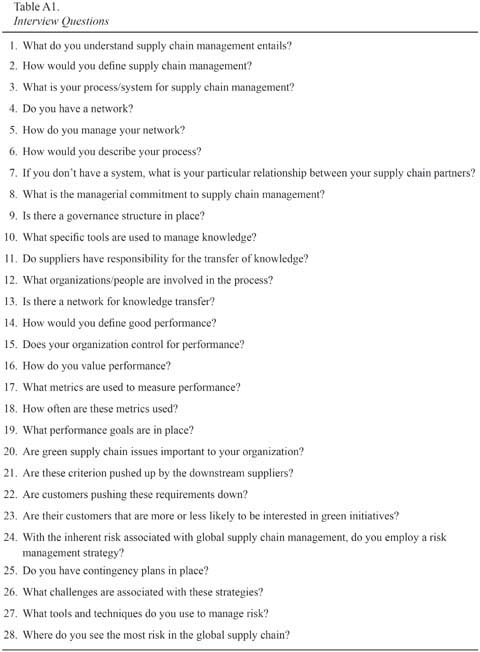

The researchers designed an interview protocol that was followed for our in-depth interviews. The interviews were conducted by two of our researchers who are fully bilingual. First, we provided interviewees with a brief description of our research project, along with definitions of the key constructs. The questions were based on existing literature and consisted of broad-open-ended questions followed by more specific, focused questions (see Table A1). This design was modeled after the data collection used by Kotabe, Parente and Murray (2007).

In order for the grounded theory to be effective, participants selected should be able to provide relevant data that displays multiple levels of understanding. Therefore, we interviewed managers involved in making and executing supply chain decisions from a variety of manufacturing companies. These firms included large multi-nationals operating in manufacturing industry in Mexico within the following industries: Automotive, electronics and computer, medical devices, and IT. We interviewed managers and executives at varying levels in the organizations to provide a different view on the practice of supply chain management within their firm. Two respondents from each focal company were interviewed; typically one general manager and one functional manager. In addition, functional supply chain managers for one or two suppliers were also interviewed.

Among the various enclaves or clusters of maquiladora manufacturing, few have been as key to Mexicos competitiveness as the State of Jalisco and its capital of Guadalajara. The region and municipality are populated by hundreds of firms, from small service providers to multinational companies, with the largest concentration in electronics and information technology. Therefore, the company interviews were conducted in Guadalajara.

Representatives from eight focal companies were consulted, using multi-level interviews within most of these focal firms to accurately determine the level of knowledge and involvement in supply chain management. The focal firms interviewed included IBM, Hewlett-Packard, Flextronics, Jabil, Foxconn, Sanmina SCI, Continental and Fresenius. Additionally, eight suppliers related to the focal companies were included as part of the sample to determine the level of relationship existent in the supply chain.

The research team conducted a total of 24 in-depth interviews of 60 minutes each. A pre-scripted instrument was followed in every one that included open-ended questions covering seven areas of supply chain management. Questions were organized to be of increasing focus as the interview progressed. In the event respondents were unable to answer a question, definitions were provided to allow the respondent to continue. Interviews were conducted in English when appropriate and detailed notes were taken of the responses provided by the participants. At the conclusion of each session, a brief summary was provided by the interviewer to provide a final opportunity for feedback from the subject. All interviews were followed by a tour of the facilities. The notes taken during each meeting were typed up and sent to interviewees to ensure accuracy of our information. The interviews were conducted between December 2008 and May 2009 in the state Jalisco, Mexico.

ANALYSIS AND DISCUSSION

How do firms conceptualize and define supply chain management?

While we found no two responses alike among top managers and functional managers, we did find general agreement that supply chain management entails, at the minimum, a broad range of business functions and services including research and development, production, forecasting, purchasing, logistics, marketing, sales, information, finance and customer service. This understanding encompasses the very model of supply chain management elucidated by Mentzer et al. (2001a) (see Figure 1).

In certain instances, especially with respect to price-sensitive and low-margin related inputs, purchasing and logistics were deemed paramount. In the case of industrial firms in the highly competitive automotive sector, such as Continental, as well as electronics suppliers to a variety of large global firms (the cases of Flextronics and Jabil), just-in-time inventory management and customer service weighed heavily in their supply chain decision making.

While the interviewed firms may have placed varying degrees of importance to the nearly dozen aspects of supply chain management cited above, none discounted the importance of each of those elements. In general, almost all firms conceptualized and defined supply chain management as a coherent set of approaches for efficiently integrating suppliers, manufactures, warehouse and distribution centers and retail establishments for the purpose of producing and distributing merchandise in the right quantities to the right locations and at the right time in order to minimize system wide cost while meeting service level requirements (Simchi-Levi et al., 2004). As one manager, Roberto Ayala of Foxconn, indicated: It is not just about having access to the raw materials at a competitive price. Time, location, information, and getting the product to the final destination while ensuring quality throughout is of critical importance to our firm.

Another manager asserted that supply chain management has to do with the logistics of information flows and, in general, the ability to connect demand with the supply of components including the reaction speed of the whole chain. As an example, he mentioned how important it is to have state-of-the-art information systems for the entire chain. It might take days when a distributor cancels an order in Colombia until a supplier in Taiwan is aware of it. According to Roberto Hernandez of HP: That kind of dysfunctionality is highly disruptive to the entire supply chain and costly, and [it is] prejudicial overall to the customer. In accordance with this and as mentioned by Julio Acevedo, a top manager of HP: Our supply chain management is very complex; we are in 170 countries, which mean 170 customers and using 400 suppliers. For that reason, our supply chain is one of the most complexes at a global level.

From the supplier point of view there was no disagreement on the conceptualization and definition of supply chains. This is not to say there is no normative disagreement in the relationship of supply chain management between buyers and suppliers. As in all commercial relationships between vendors and their customers, perceptions vary widely with respect to operational features such as on-time deliveries, quality, reporting, financial management and overall customer relationships. Recognizably there will be different interpretations in complying with the different matrix of buyer supplier performance.

As one of the managers of Ryder a supplier for HP points out: Supply chain management ...is the coordination to move materials from a firm to their consumers and the information flow needed for that purpose. In almost all cases suppliers mention and emphasize the importance of both coordination and an understanding of their buyers´ business in order to fulfill their requirements on time and according to their standards.

Also, in the case of the suppliers, it is important for both buyers and sellers to understand at what stage of the supply chain they are since this has different types of implications. As indicated by Alejandro Vazquez of ROHM Semiconductor, a supplier of Continental: Supply Chain Management entails all the activities involved in supplying materials and saving time and cost from requirement to the fulfillment of a given need. It entails all the production chain including suppliers, the manufacturer and its customers. Since we are at the beginning of the chain, we help to plan materials´ supply.

What kind of processes and systems do supply chain participants utilize in their enterprises?

The researchers found a rich body of responses to this question. The general sense and approach to processes and systems from the sampled companies is best captured by IBM General Manager Eugenio Goddard who cited the process and system for supply chain as a dynamic one in which continuous improvement and reinvention serve as the centerpiece:

We make sure at all times that suppliers know what IBM is doingwe work very closely with them. In this way our suppliers can direct and execute their production based upon what IBM produces and plans to produce. This makes the whole process more responsive and adaptable across the board.

Although there are many similarities in the process and the systems among buyers and suppliers, each industrial sector possesses unique features in this regard. For example, in the electronics component sector, for both Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEM) and contract manufacturers, an Approved Vendor List (AVL) is of utmost importance. In this process all materials have to be approved by the customers from the largest components to the smallest inputs. Buyers demand lowest point pricing and optimal efficiency in delivery to lower the cost and ensure speed one of the most vital characteristics in the quick cycle of electronic components industry. Suppliers have very little leeway to substitute components or utilize any vendor not pre-approved by their customer. At the same time, suppliers as well as buyers scan the globe constantly in search of alternative suppliers of inputs who can furnish high quality materials quickly, efficiently, and at the lowest possible price.

Although processes and systems for supply chain are understandably centralized at the top of the organization, with a rigorous system of monitoring, reporting and adjusting, it is also true that companies decentralize selected operational functions as pointed out by Roberto Martínez from HP:

There is no single process, there are many demand planning, administration of the HP net, MRP [material requirements planning] systems, and supply administration systems. There are also informal as well as formal processes managed from consumers to the corporation. There are systems and processes in all the distribution channels, since there are many different ways of selling.

As for the utilization of networks, the understanding of the concept, as well as its implementation, varies widely among general and functional managers and from suppliers. Initially, respondents understood networks to be electronics information systems purely technical in purpose and function. However, following the broader explanation from the researchers, the interviewees understood networks to be a set of commercial and social relationships.2

A number of firms consider their networks to include suppliers, customers, shareholders, employees, their financial institutions and the community at large. Typical were the comments of one supplier who stated: Our networks encompass more than customers. The means of designing, managing, and maintaining these communication networks cover the broad spectrum of electronic interconnection including CRM, intranet, and ERPs, through our electronic and interpersonal means of communication, all parties can work to ensure the business objectives are me.

As for managing the networks, several respondents indicated that their networks are managed in mostly a centralized fashion but with great leeway to adapt their systems. Individual business units often customize their own systems for supply chain management. One firm created two organizations of network management–one for purchasing and one for negotiations with suppliers. Transparency and privacy were cited as two of the most important features of effectively managed networks. Trust, accountability and customer satisfaction were also cited by a number of respondents as a very important aspect of network communications.

A number of firms described their network as a series of sub processes: acquisitions and procurement, logistics, warehouse management, and VMI (vendor managed inventory). According to Carlos Gomez of Continental:

Our network process flows from the conceptualization and design of the idea, testing, sourcing, validation, implementation, SOP, controlling, monitoring and end-of-life. For each stage in the network management process there is a clear definition of position and duties. There is no regional or location process--it is global at its core.

For other firms that rely heavily on their networks, they cite demand planning--which gives a short and a long term forecast--, product life cycle monitoring and other process functions, all derived from MRP. The researchers found that in cases where firms offered an extensive portfolio of products and that those products utilized hundredseven thousands of inputsbut that qualified suppliers were few in number, the greater the likelihood that these multinationals relied on systems, processes, and networks for SCM.

In essence, through the use of a broad range of information technology systems, such as ERP, SAP R3, and personal communications, both buyers and suppliers are able to tie together all aspects of their supply chain management systems and ensure transparency, productivity and efficiency in real time.

How committed is senior management to SCM?

If indeed as Ketchen and Hult (2007) observe, that business competitiveness in the 21st century will be based not on competitiveness among firms but among supply chains, senior management in our sample of companies would fully agree. According to our respondents, headquarters senior executives either fully support or do not interfere with the design, planning, implementation and monitoring of supply chain operations. To illustrate, in the case of Flextronics, company commitment means that all materials workers are fully integrated in the supply chain management system--each area having their appropriate responsibility to ensure that their contributions to SCM are critical and sustainable. A senior materials vice-president is located in China where most of the firms suppliers are based in order to ensure that production and output are efficient and every aspect of the China-based supply chain system from sourcing to exporting runs at an optimal level of performance.

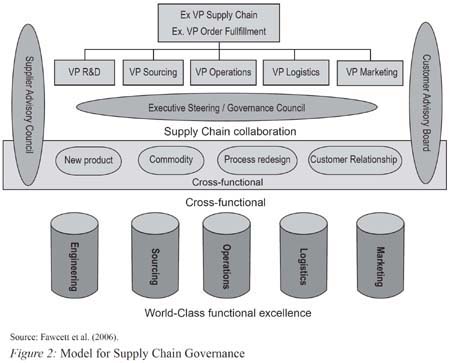

In a number of instances, supply chain management is emerging alongside finance and marketing as a path for fast track promotion and advancement to senior leadership positions at the national and global level of the firm. In terms of governance structures the situation varies widely. It is worth citing Fawcetts model for supply chain governance (see Figure 2).

While no firm in our sample manifested Fawcetts composite model with separate vice-presidents for R&D, sourcing, operations, logistics and marketing combined with an executive steering for governance counsel to oversee new product development, commodities, process redesign and customer relationship, the researchers did find management systems responsible for end-to-end SCM operations in which governance occurs in both centralized and non centralized managerial systems working closely together. In several companies, each business unit has its own supply chain manager that reports to the supply chain vice-president at regional or corporate headquarters. One of the most sophisticated examples, Jabil Corporation, possesses three main divisions, each with a SCM vice-president who reports to the division president who, in turn, reports to the CEO. The researchers found, however, that formal governance structures among suppliers were absent despite the fact that all suppliers maintained a heavy commitment to supply chain management as a business function.

What role does performance play in supply chain management?

Recognizing the increasing competition among global firms and their suppliers, performance issues embody the very core of the companys survival. Mexican based firms and their supplier networks are no different in how they value, track, measure, and control for financial, production and market variables such as productivity rates, return on assets and investment, market share and other performance metrics.

The researchers posed a number of related questions to general and functional managers as well as their suppliers. We began by querying them on their definition of good performance; in general the respondents cited customer satisfaction and optimal use of resources as most important. Additional factors included in their criteria were worker and shareholder satisfaction, delivery quality and cost along with meeting (but preferably exceeding) all objectives. The balanced scorecard concept was found to be widely used in sending and receiving freight, inventories, cost and delivery times. As Rogelio Mier Bueno of Sanmina SCI stated: A company that delivers products on time with the optimal requirements, while creating and sustaining long term relationships with all parties in the firms business networks, clearly will have achieved excellent performance.

Controlling for performance is vitally important in an enterprise to achieve its objectives. The firms in our sample take a variety of approaches in controlling for their performance. Most employ internal and external controls in which time, cost and relationships with customers are paramount. One organization cited bonus pay and metrics based on Wall Street evaluation inventory turns. Another employs weekly reviews of key metrics on-site and takes preventive and corrective actions. And still others in our sample focus on annual savings targets, quality and deliveries. Quality, including quick identification of problems and swift corrections of rejected merchandise, are vital to the control for performance for all firms in our sample.

How companies value performance varies widely, as well. Most important to the enterprises in our sample are customer and shareholder satisfaction, in which the quality and consistency of customer service and shareholder satisfaction with the firms financial performance are really significant. Most companies manifest their value of performance through financial rewards to employees and managers. How employees achieve predetermined targets --such as productivity goals, cash management, market share and achieving sales targets-- result in tangible rewards. In one firm, bonuses are paid to managers with 60% based on financial performance and the remainder on customer satisfaction and cash performance. In the case of Continental, the value they place on performance is manifested in the promotion of people to higher level responsibilities along with higher salaries and bonuses. Selecting highly talented individuals for training is also important with such decisions made through collective meetings. As purchasing manager, Guillermo Schmidhuber expressed: Bonuses are paid when all targets are reviewed and met by the employee. Roundtable meetings occur to identify and track talent. High potential individuals are selected and placed on a fast track.

In most cases rewards, such as bonuses and raises, are based on the negotiations at the beginning of the year. And if the employee and/or business unit can not only meet but exceed the objectives, then the financial benefits are parceled out. Indeed, as Norberto Leandro of Fresenius declared: Everything is measured against the budget. In fact, with respect to performance metrics, all respondents were in agreement that financial and customer measures of performance were the most important.

At IBM performance metrics are decided based upon the position of the employee or the function of the business unit. For example, there are metrics for cost maintenance, site availability and utilization, concrete and measurable ideas of management improvement, and control and evaluation of existing processes. In an international firm such as Continental, a global leader in automotive products, savings, quality and subsidiary performance especially in low cost countries are key measures of performance. Freight cost, labor cost, corporate income, out of the box audits, inventory turns, material cost, and control of suppliers performance are all critically important measures. According to Roberto Hernandez from Flextronics, his view, shared by most, is that different business units and functions all have different performance goals, but at the corporate level bonus payments are defined according to criteria from Wall Street.

As to how often metrics are used in evaluating performance by business units, there is wide variation. Most firms evaluate monthly; others daily, weekly, quarterly and every six months. Sophisticated management information systems allow these enterprises to closely and accurately track performance.

As for performance goals, our respondents cited financial goals, customer satisfaction, including quality and time of delivery, as the principal performance goals in place. The balanced scorecard is widely used to establish performance goals; and in the case of plant level, production component manufacturers cite defective parts per million, AD cycle time and non-conformance cost (the cost for poor quality from suppliers). For still others EBIT, on-time delivery from suppliers and company delivery time to customers are key performance goals. Finally, a number of firms also employ external criteria for performance goals. In the case of Sanmina SCI, to maintain A class status–the highest in the Kaizen program valuation--is paramount. In all cases, buyers and suppliers are fully aware of the need for continuous performance improvement and to select, adopt and adapt performance goals, measures and systems to ensure a continuous trajectory of high achievement.

What specific risk management actions do companies employ?

Offshore manufacturers in industries, with fast cycle times and based in emerging markets where a whole series of risks are present (political, economic, legal, safety), are especially challenged to plan, design and implement strategies to mitigate risk. This is particularly important for supply chains. All firms the researchers interviewed have taken specific actions from the mundane to the sophisticated for managing risk. This includes disaster recovery plans, alternative manufacturing sites and redundant suppliers. One high technology firm asserted that risk management is conducted in their regional headquarters in Miami and includes risks such as material quality, on time delivery to customers, theft and fire.

The use of redundant suppliers was cited by interviewees as essential. Companies demand written commitments from suppliers to correctly manage inventory, materials purchasing, securing customized materials and other related issues. In the case of Hewlett Packard, they utilize worldwide risk assessment systems as well as those at the plant level. As Roberto Martínez of HP asserts:

A mature prevention process includes, among other things, a mock system breakdown which could include a bomb explosion that affects SAP or an event that harms or disables key personnel. Business continuity plans are central to HPs risk management process in their supply chain.

All firms interviewed do have contingency plans in place. Some of them are developed at the corporate level; some at regional headquarters, and in all cases at the plant level. Foxconn uses Vendor Management Inventory (VMI), and the firm carefully tracks supply and demand flows so that suppliers will always have the capacity to meet Foxconn customer demands. For Continental, their contingency plans include redundant factories, two-week inventories, and careful tracking of customer demand and product cycles so as not to be stocked with obsolete inventory. It is common for corporate headquarters or regional headquarters to audit and monitor subsidiaries contingency plans on a regular basis. When asked about the challenges associated with these strategies, the comment of Roberto Hernandez of Flextronics is representative: The key challenge is that each actor in the supply chain has to understand that delivery times are compact, and that company-supplier interaction has to be close, constant, efficient and flexible.

Dynamic industries such as electronics and high technology must contend with globalization often moving faster that their abilities to adjust. Life cycles for products are becoming shorter, and companies must be able to react to demand fluctuations more efficiently and responsibly than ever before. Companies must have the capacity to track and purchase inputs. In other words, security, terrorism and black markets could produce devastating impacts to producers and customers. According to Ernesto Sanchez of Jabil, intellectual property is a key determinant of competitiveness. For him and several others, Mexico provides a superior environment than China for intellectual property protection.

For all firms, maintaining a good information base to track cost and input availability so as not underbuy or overbuy is extremely important. As for tools and techniques to manage risks, the respondents have an arsenal that covers the gamut. This includes SAP, ERP for IT, risk management educational programs, business continuative plans, six sigma, redundant suppliers (as previously mentioned), and on average two weeks inventory of supplies. Norberto Leandro of Fresenius emphasized: Corporate headquarters is ready and willing to work with their subsidiaries in identifying and implementing the most appropriate tools and techniques for risk management that allow both headquarters and the subsidiaries to efficiently and effectively manage a variety of risks.

When asked about the most risk in the global supply chain, all firms cited energy costs, transportation bottlenecks, infrastructure, and security (both local crime and theft, as well as global terrorism). The price of raw materials, the shortness of product life cycles and protectionism were deemed of equal importance.

CONCLUSION

Our qualitative assessment of the sample firmsmultinational buyers along with suppliersconfirms that a symbiotic triad of resources, networks, and performance are key determinants of strategic risk management in supply chains in one important emerging marketMexico.

Continuous improvement and reinvention of systems and processes in supply chains are commonly shared traits among the companies we evaluated. The kind of resources, amount, and form of application may vary, but the concept of resources as a driver of supply chain management and corporate competitiveness is inarguable. Management at headquarters, regional, and subsidiary levels all recognize the vital importance and need to dedicate significant resources to SCM. In fact, along with finance, marketing and production management, SCM is emerging as a hot ticket for corporate promotion and advancement to leadership positions throughout the firm.

For the sample firms, networks were key elements and included not just customers but suppliers, shareholders, services institutions (banks, insurance companies), and civil society. Communication with these different actors was regarded as a business process to operate continuously, from design to implementation, monitoring, and feedback activity. Whether centralized or decentralizedand several firms had both network management systems operating simultaneouslytransparency, privacy, accountability and customer satisfaction were fundamental. As for the operational dimension of networks, a central part of the network operations embodied interactive systems for sourcing, controlling, monitoring and end-of-life. All of these, including product life cycle monitoring, were derived from MRP systems.

As for performance, these issues are directly related to risk mitigation and, fundamentally, the very essence of the firms survival. Mexican-based companies and their supplier networks value, measure and monitor performance metrics just as their counterparts in other countries. However, how businesses value performance varies widely, as well. The researchers found that customer and shareholder satisfaction ranked extremely high, with financial performance being the most important. In addition to mitigating risk through employee recruitment, selection, and evaluation, the companies in our sample employed a variety of metrics in evaluating the performance by business units. Performance goals also included quality and time of delivery, and a number of firms employed the balanced scorecard to establish performance goals.

A framework comprised of the symbiotic triad of resources, networks, and performance for analyzing strategic risk management in supply chains is a viable paradigm for studying supply chains in emerging markets. As business competition increases and pressures to mitigate risk mount, due to internal as well as external challenges in global markets, international companies and their suppliers will need to institute policies to increase productivity, efficiency, and communication, among and between themselves.

The current study is limited in its generalizability for two reasons. In the first place, recognizably this qualitative study involves one country only and a small sample of firms. Future research should extend this pilot research to other countries and industries (beyond electronics and information technology) and utilize a larger sample of firms. In,the second place, the qualitative research should be complemented with quantitative assessments using structured survey questionnaires that lend themselves to multivariate analyses.

References

Arroyo, P., Gaytan, J., & de Boer, L. (2006). A survey of Third Party Logisitics in Mexico and a Comparison with reports on Europe and USA. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 6, 639-667. [ Links ]

Barney, J. D. (1991). Firm resources sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99-120. [ Links ]

Barratt, M., & Oke, A. (2007). Antecedents of supply chain Visibility In Retail Supply Chains: A Resource-Based Theory Perspective. Journal of Operations Management, 25(6), 1217-1233. [ Links ]

Bhagwat, R., & Sharma, M. K. (2007). Performance Measurement Of Supply Chain Management: A Balanced Scorecard Approach. Computers and Industrial Engineering, 53, 43-62. [ Links ]

Cañas, J., & Gilmer, R. W. (2009). The maquiladoras changing geography. Southwest Economies, Second Quarter, 10-14. [ Links ]

Capó-Vicedo, J., Tomás-Miquel, J. V., & Expósito-Langa, M. (2007). La gestión del conocimiento en la cadena de suministro. Análisis de la influencia del contexto organizativo. Información Tecnológica, 18(1), 127-135. [ Links ]

Carter, J. R., & Ellram, L. M. (1994).The Impact of Interor-ganizational Alliances In Improving Supplier Quality. International Journal of Physcial Distribution & Logistics Management, 24(5), 15-23. [ Links ]

Chan, F. T. S.. (2003). Performance Measurement in a Supply Chain. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology, 21, 534–548. [ Links ]

Cheng, S. K., & Kam, B. H. (2008). A Conceptual Framework for Analysing Risk in Supply Networks. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 22, 345-360. [ Links ]

Chow, W.S., Madu, C.N., Kuei, C.H., Lu, M.H., Lin, C., & Tseng, H. (2008). Supply chain management in the US and Taiwan: An empirical study. Omega International Journal of Management Science. 36, 665-679. [ Links ]

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (1990). Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory, Procedures and Techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Dierickx, I., & Cool, K. (1989). Asset Stock Accumulation and Sustainability of Competitive Advantage. Management Science, 35(12), 1504-1511. [ Links ]

Fawcett, S. E., Ogden, J. A., Magnan, G. M., & Cooper, M. B. (2006). Organizational Commitment and Governance for Supply Chain Success. International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management, 36(1), 22-35. [ Links ]

Ford, D., Gadde, L. E., Håkansson, H., Lundgren, A., Snehota, I., Turnbull, et al. (1998). Managing business relationships. London: Wiley. [ Links ]

Granovetter, M. S. (1973). The Strength of Weak Ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78(6), 1360-1380. [ Links ]

Grant, R. M. (1991). The Resource-Based Theory of Competitive Advantage: Implications for Strategy Formulation. California Management Review, 33(3), 114-135. [ Links ]

Håakansson, H., & Ford, D. (2002). How Companies Interact in Business Networks. Journal of Business Research, 55, 133-139. [ Links ]

Håakansson, H., & Snehota, I. (1995). Developing relationships in business networks. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Harland, C. M. (1996). Supply Chain Management: Relationships, Chains and Networks. British Journal of Management, 7, 63-80. [ Links ]

Harland, C. M., & Knight, L. A. (2001). Supply Network Strategy: Role and Competence Requirements. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 21(4), 476-489. [ Links ]

Hausman, A. & Haytko, D. L. (2004). Examining key Factors Of Supply Chain Optimization: The Maquiladora Example (Working Paper 2004-20). Edinburg, TX: University of Texas - Pan American. [ Links ]

Haytko, D. L., Kent, J. L., & Hausman, A. (2007). Mexican maquiladoras: helping or hurting the US/Mexico cross-border supply chain? International Journal of Logistics Management, 18(3), 347-363. [ Links ]

Holcomb, T. R., & Hitt, M. A. (2007). Toward a Model of Strategic Outsourcing. Journal of Operations Management, 25(2), 464-481. [ Links ]

Johanson, J., & Mattsson, L. G. (1987). Interorganizational Relations in Industrial Systems: A Network Approach Compared with Transaction Cost Approach. International Studies of Management and Organization, 17(1), 34-48. [ Links ]

Ketchen, D. J., Jr., & Hult, G. T. M. (2007). Bridging Organization Theory and Supply Chain Management: The Case of Best Value Supply Chains. Journal of Operations Management, 25, 573-580. [ Links ]

Kotabe, M., Parent, R., & Murray, J.Y. (2007). Antecedents and Outcomes of Modular Production in the Brazilian Automobile Industry: A Grounded Theory Approach. Journal of International Business Studies, 38(1), 84-106. [ Links ]

Krause, D. R., Scannell, T. V., & Calantone, R. J. (2000). A Structural Analysis of the Effectiveness of Buying Firms Strategies to Improve Supplier Performance. Decision Sciences, 31(1), 33–55. [ Links ]

Krishnan, M., Parente, E., & Shulman, J. A. (2007). Understanding Latin Americas supply chain risks. McKinsey, May, 1-4. [ Links ]

Mentzer, J. T., De Witt, W. K., James, S., Min, S., et al (2001a). Defining Supply Chain Management. Journal of Business Logistics, 22(2) 1-25. [ Links ]

Mentzer, J. T., Flint, D. J., & Hult, G. T. M. (2001b). Logistics Service Quality as a Segment-Customized Process. Journal of Marketing, 65(4), 82–104. [ Links ]

Miles, R. E., & Snow, C. C. (1978). Organizational Strategy, Structure, and Process. New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Oliver, C. (1990). Determinants of inter-organizational relationships: Integration and figure directions. The Academy of Management Review, 15(2), 241- 265. [ Links ]

Ordóñez, S. (2005). Empresas y cadenas de valor en la industria electrónica en México. EconomiaUnam, 2(5), 90-111. [ Links ]

Peteraf, M. A. (1993). The Cornerstones of Competitive Advantage: A Resource-Based View. Strategic Management Journal, 14(3), 179-191. [ Links ]

Porter, M. (1990). The Competitive Advantage of Nations. New York: Free Press. [ Links ]

Power, D. J., Sohal, A. S., & Rahman, S. U. (2001). Critical Success Factors in Agile Supply Chain Management: An Empirical Study. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logisitics Management, 31(4), 247-265. [ Links ]

Rungtusanatham, M., Salvador, F., Forza, C. & Choi, T. Y. (2003). Supply chain linkages and operational performance. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 23(9), 1084-1099. [ Links ]

Sahin, F., & Robinson, E. P. (2002). Flow Coordination and Information Sharing in Supply Chains: Review, Implications and Directions for Future Research. Decision Sciences, 33(4), 505-536. [ Links ]

Sánchez, J., Elías, J., & García, H. (2002). Marco conceptual de la cadena de suministro: un nuevo enfoque logístico. Publicación Técnica. México D. F., México: Investigación Organizacional del Instituto Mexicano de Transporte. [ Links ]

Simchi-Levi, D., Kaminsky, P., & Simchi-Levi, E. (2004). Managing the Supply Chain: The Definitive Guide for the Business Professional. New York: McGraw-Hill Professional. [ Links ]

Soler, V. C. & López, Y. Y. (2005). Nueva filosofía de trabajo entre fabricantes y distribuidores: Colaborando tras la consolidación de ECR. Investigación y Marketing, 90, 27-33. [ Links ]

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research:Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Tan, K-C., Kannan, V. R, & Handfield, R. B. (1999). Supply Chain Management: An Empirical Study of its Impact on Performance. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 19(10), 1034-1052. [ Links ]

Thorelli, H. B. (1986). Networks: Between markets and hierachies. Strategic Management Journal, 7(1), 37-51. [ Links ]

Turnbull, P., Ford, D., & Cunningham, M. (1996). Interaction, Relationships and Networks in Business Markets: An Evolving Perspective. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 11(3/4), 44-62. [ Links ]

Unger, K. (2003). Los clusters industriales en México: Especializaciones regionales y la política industrial. Santiago de Chile: CEPAL. [ Links ]

United States General Accounting Office (2003). International Trade: Mexicos maquiladora Decline Affects Us - Mexico Border Communities and Trade; Recovery Depends in Part on Mexicos Actions. Washington, D. C.: General Accounting Office Reports. [ Links ]

Uzzi, B. (1997). Social Structure and Competition in Interfirm Networks: The Power of Embeddedness. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42, 35-67. [ Links ]

Wasserman, S., & Faust, K. (1994). Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Watts, C. A. & Hahn, C. K. (1993). Supplier development programs: An empirical analysis. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 29(2),10-17. [ Links ]

Wernerfelt, B. (1984). A resource-based view of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 5, 171-180. [ Links ]

Wu, F., Yeniyurt, S., Kim, D., & Cavusgil, S. T. (2006). The Impact of Information Techonology on Supply Chain Capabilities and Firm Performance: A Resource-Based View. Industrial Marketing Management, 35(4), 493-504. [ Links ]

Notas de pie

1 Resources include organizational systems and processes, information, knowledge, capabilities, partners and alliances, and other assets.

2 We explained networks and network position as a set of a firms relationships, including obligations and resource commitments, particularly as they regard buyer-seller interactions (see Turnbull, P., Ford, D., & Cunningham, M. (1996)).

Anexos