Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Science

Print version ISSN 2077-1886

Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Science vol.16 no.30 Lima June 2011

ARTICLES

On welfare effects of horizontal mergers with product differentiation

Sobre los efectos benéficos en las adquisiciones empresariales con productos diferenciados

Marc Escrihuela-Villar1

1. Profesor de Economía Aplicada de la Universitat de les Elles Balears. <marc.escrihuela@uib.es>

I am grateful to Ramón Faulí-Oller for his advice and encouragement; to Antonio Jiménez, Michael Margolis, Joel Sandonís, Luís Corchón, Pedro Barros, Javier López-Cunyat and Inés Macho for their invaluable comments.

The current version of the paper has benefited from helpful comments of the seminar participants at the European Network on Industrial Policy (EUNIP) 2010 International Conference. Financial support by the Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia, through its project Políticas de salud y bienestar: incentivos y regulación (Ref: ECO2008-04321/ECON), is gratefully acknowledged. Any remaining errors are my own.

ABSTRACT

We use a non-spatial (Chamberlinian) product differentiation model to analyze the welfare effects of horizontal mergers with quantity competition. We argue that (i) mergers can be welfare enhancing if the degree of product differentiation increases after the merger; and, (ii) privately profitable mergers can also increase welfare. Consequently, in this paper we demonstrate that the degree of product differentiation is a crucial factor to assess the welfare effects of a merger.

Keywords: Horizontal mergers, product differentiation, welfare.

RESUMEN

En este artículo usamos el modelo de diferenciación no-espacial de producto (Chamberliniano) para analizar los efectos benéficos en las adquisiciones empresariales horizontales con cantidad de competencia. Aquí argumentamos que (i) las adquisiciones empresariales pueden ser promovedoras del beneficio si el grado de diferenciación de productos aumenta después de la absorción; y, (ii) las adquisiciones privadas lucrativas también pueden beneficiosas. Consecuentemente, este artículo demuestra que el grado de diferenciación de producto es un factor crucial para evaluar los efectos benéficos de una adquisición empresarial.

Palabras claves: Adquisiciones empresariales horizontales, diferenciación de productos, beneficio.

INTRODUCTION

Traditional merger analysis is difficult to implement when evaluating mergers in industries with differentiated products. Broadly, the agencies consider two basic theories of competitive effects. "Coordinated effects" arise if the merger would make collusion between the merged firm and its rivals more likely, or make their behavior more accommodating. "Unilateral effects" arise if the merger would give the merged entity a unilateral incentive to harm consumers1. This approach, however, does not always work well in the large class of mergers in which the merging firms sell differentiated products and the agencies must weigh concerns about unilateral effects. Product differentiation can make defining the relevant market problematic, notably because products must be ruled "in" or "out". In any case, there is a common perception that the degree of product differentiation is a crucial determinant of the welfare effects of horizontal mergers.

Oligopoly theory in a collusive environment (Farrell & Shapiro, 1990; Deneckere & Davidson, 1985; Escrihuela-Villar, 2008) generally predicts that horizontal mergers will lead to at least marginally higher prices if they generate no efficiencies when products are homogeneous. This approach, however, leaves out product differentiation. On the contrary, an extensive empirical literature has tried to explain the welfare effects of horizontal mergers with product differentiation. Generally, in a differentiated product context, mergers that raise prices still may enhance total welfare (see for instance Werden & Froeb, 1994; Ivaldi & Verboven, 2005). A very good example is the merger proposed in 2007 between Whole Foods and Wild Oats, two chains of grocery stores specializing in natural and organic food. Seeking to block the merger, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) argued that Whole Foods and Wild Oats competed in a market for "premium natural/organic supermarkets". Later, the District Court stated: "[If] the relevant product market is, as the FTC alleges, a product market of premium natural and organic supermarkets consisting only of the two defendants and two other non-national firms, there can be little doubt that the acquisition of the second largest firm in the market by the largest firm in the market will tend to harm competition in that market. If, on the other hand, the defendants are merely differentiated firms operating within the larger relevant product market of supermarkets, the proposed merger will not tend to harm competition". Hence, according to the Court interpretation, the degree of product differentiation is the crucial factor to assess the welfare effects of a horizontal merger.

The main purpose of this paper is thus to study to what extent the degree of product differentiation is a key factor in evaluating a horizontal merger. We address this issue by developing an oligopoly model with nonspatial (Chamberlinian) product differentiation where firms compete in quantities. We show that any merger might be welfare enhancing if the degree of product differentiation increases after the merger. The intuition is that an increase in product differentiation reduces merger profitability, but increases total surplus in such a way that when products become more differentiated, the increase in welfare offsets the negative effects on surplus of the reduction in competition caused by the merger.

We believe that the main interpretation of our result is that, without significant cost synergies, profitable mergers may also raise welfare whenever products are differentiated. Consequently, when assessing the welfare effects of horizontal mergers, besides the cost synergies, the firms possible effort to differentiate its products should also be taken into account. We also prove that in absence of cost synergies derived from the merger, a privately profitable merger involves a number of participants such that this merger only reduces welfare when the post-merger value of the product differentiation does not increase sufficiently. Then, it seems plausible to assume that, even without significant cost synergies, a proposed merger could be allowed by arguing that products are differentiated enough whenever the degree of differentiation between products increases sufficiently after the merger. The rest of the paper is structured as follows: In section 2, we present the model and the welfare effects of mergers. We conclude in section 3. All proofs are grouped in the Appendix.

THE MODEL AND RESULTS

We consider an industry with N ≥ 2 firms indexed by i = 1,..., N. where firms compete in quantities producing non-spatial horizontally differentiated products such as that that the degree of differentiation between the products of any two firms is the same. We normalize marginal cost to zero. With an abuse of notation we

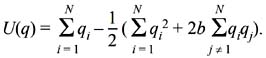

denote by qi the quantity produced of good i by firm i, meaning that each firm produces a single differentiated product. Following Spence (1976 a, b) and Dixit and Stiglitz (1977), we consider that this industry has a representative consumer with utility given by the function U(q), where q is the quantity vector and

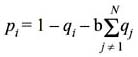

Then, the demands for the differentiated products are derived from the solution to the program maxqU(q) – pq. For positive demands and i = 1, ..., N, the inverse demand function exhibits a Chamberlinian symmetry:

where pi denotes the price of good i and qj the quantity sold of good j. It is assumed b > 0 where b can be interpreted as the parameter to measure the common degree of differentiation between any two products in the industry. Hence, b = 0 implies that the products are completely independent and b = 1 indicates that they are perfect substitutes. The value range for b implies that the products are viewed as substitutes rather than complements.

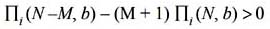

Consider the incentives of firms to merge2. In our setting, in absence of cost synergies, once M + 1 firms have merged there will be N – M firms (and consequently N – M products) in the market3. Let us denote the equilibrium profits obtained by firm i by ∏i (N, b). Then, a merger is considered to be (privately) profitable if the profits of merging firms increase after merger which implies that

From Deneckere and Davidson (1985), we know that with price competition, since reaction functions are typically upward sloping, mergers of any size are profitable4. On the contrary, mergers with quantity competition are (generally) not profitable (see Salant et al., 1983). Our model proves that with quantity competition mergers are less profitable when products are more differentiated.

Proposition 1: The number of firms required for a merger to be profitable decreases with b.

Intuitively, in absence of synergies derived from a merger, a merger loses attractiveness as an anti-competitive device when products are more differentiated. In other words, Salant et al. (1983) demonstrate that the minimum profitable merger, under Cournot oligopoly theory, involves at least 80 percent of the firms in the industry. Therefore, since the present model encompasses the Cournot case if b = 1, Proposition 1 shows that this minimum requirement is larger when b decreases. On the other hand, following Vives (1999) and since marginal costs of production are equal to cero, total surplus or welfare is given by U(q). Then, and in line with previous results (see Spence, 1976a, b and Lancaster, 1990, for a survey about the economics of product variety), it can be easily proved that total surplus increases with the degree of product differentiation. Consequently, there are two different forces at work when products become more differentiated. First, mergers reducing competition are less profitable, and second, welfare increases because consumers are better off when the degree of product differentiation increases. The point is whether there exists an increase in the degree of product differentiation such that welfare may increase. Therefore, considering a possible increase in the degree of product differentiation after the merger, the following result can be drawn:

there is always a post-merger degree of product differentiation above the pre-merger one where all mergers are also welfare enhancing.

The intuition behind Proposition 2 is as follows: obviously, mergers that do not reduce costs and only reduce competition also reduce welfare. However, if after the merger the degree of product differentiation would increase, consumers welfare would also increase. In this case, although mergers tend to reduce welfare, if the number of merging firms is below a certain threshold, we can always find a post-merger degree of product differentiation such as that welfare also increases. As a consequence, an interesting interpretation of the last result is that when evaluating mergers in industries with differentiated products, it should also be considered which the potential degree of product differentiation is after the merger, since this could be used as a plausible screen for likely welfare effects. The natural question arises if whether when mergers are privately profitable an increase in the degree of product differentiation can render mergers also welfare enhancing.

Proposition 3: A profitable merger can also be welfare enhancing when the increase in the degree of product differentiation is high enough.

For a merger to be profitable a minimum number of firms have to be involved in the merger. On the contrary, Proposition 2 states that only when the merger involves less than a certain number of firms, the merger can enhance welfare via an increase in the degree of product differentiation. Proposition 3 comes from the fact that the reduction in competition needed for the merger to be profitable is large enough for the merger to reduce welfare only when the post-merger degree of product differentiation is not large enough. In other words, whenever the differentiation between the products can be sufficiently increased, profitable mergers may also increase welfare.

CONCLUDING COMMENTS

We have developed a theoretical framework to study the effect on welfare of mergers in a market with product differentiation, a problem that, to the best of our knowledge, has not been extensively considered. We prove that the results by Salant et al. (1983) are sensitive to the assumption of homogeneous products. We show that the degree of product differentiation is a crucial determinant of profitability and welfare effects of mergers in such a way that, if the degree of product differentiation increases a merger, it may also be welfare enhancing. Interestingly, these results hold in the absence of synergies or fixed cost economies. On the other hand, when the merger is privately beneficial, welfare can also be increased when the post-merger degree of product differentiation increases sufficiently. Our results thus provide also the interpretation that the negative effects on welfare of the well-known merger paradox might vanish when we consider the degree of product differentiation.

The framework we have worked with is, admittedly, a particular one. To analyze real-world cases of mergers, firmscapacities, cost asymmetries or variable cost synergies should also be considered. We believe that those are subjects for future research.

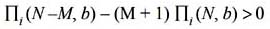

APPENDIX

REFERENCES

Deneckere, R., & Davidson, C. (1985). Incentives to Form Coalitions with Bertrand Competition. The RAND Journal of Economics, 16(4), 473-486.

Dixit, A., & Stiglitz, J. (1977). Monopolistic Competition and Optimum Product Diversity. The American Economic Review, 67(3), 297-308.

Escrihuela-Villar, M. (2008). Partial Coordination and Mergers among Quantity-Setting Firms. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 26, 803-810.

Farrell, J., & Shapiro, C. (1990). Horizontal Mergers: An Equilibrium Analysis. American Economic Review, 80, 107-126.

Ivaldi, M., & Verboven, F. (2005). Quantifying the Effects from Horizontal Mergers in European competition Policy. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 23(9-10), 669-691.

Lancaster, K. (1990). The Economics of Product Variety: A Survey. Marketing Science, 9(3), 189-206.

Lommerud, K. E., and S0rgard, L. (1997). Merger and Product Range Rivalry. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 16(1), 21-42.

Prokop, J. (1999). Process of Dominant-cartel Formation. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 17, 241-257.

Salant, S., Switzer, S., & Reynolds, R. (1983). The Effects of an Exogenous Change in Industry Structure on Cournot-Nash Equilibrium. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 98(2), 185-99.

Spence, M. (1976a). Product Differentiation and Welfare. Papers and Proceedings of the Eighty-eighth Annual Meeting of the American Economic Association. The American Economic Review, 66(2), 407-414.

Spence, M. (1976b). Product Selection, Fixed Costs, and Monopolistic Competition. The Review of Economic Studies, 43(2), 217-235.

Vives, X. (1998). Oligopoly Pricing: Old ideas and New Tools. Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Werden, G., & Froeb, L. (1994). The Effects of Mergers in Differentiated Products Industries: Logit Demand and Merger Policy. International Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, 10(2), 407-426.

-

See for instance the guidelines on the assessment of horizontal mergers of the Official Journal of the European Union (2/5/2004).

-

We do not consider here the process of endogenous merger formation. Its consideration probably requires a set-up in which the merger formation game is in a sequential fashion similar to Prokops (1999) sequential cartel formation process. Otherwise, we would always have trivial Nash equilibria in which no firm would merge. This is an issue not raised here and left for future research.

-

We avoid integer problems following the standard approach in the literature on oligopolistic interaction, which consists of treating the number of firms as a continuous variable. We also note that, in our setting, a merger implies a reduction in the number of products. Conversely, and in a different setting, Lommerud and S0rgard (1997) consider the number of brands as a choice variable. This is an issue not raised here and left for future research.

-

Note that for the value range for b assumed, with price competition and product differentiation, reaction functions are also upward sloping.

Received date: January 6, 2011

Accepted date: January 14, 2011