Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Science

Print version ISSN 2077-1886

Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Science vol.17 no.32 Lima June 2012

ARTICLES

Effects of Activist shareholding on corporate social responsibility reporting Practices: an empirical study in Spain

Efectos del accionariado activista en las políticas de información sobre responsabilidad social corporativa: un estudio empírico en España

José Manuel Prado-Lorenzo1 ; Isabel María García-sánchez2 ; Isabel Gallego-Álvarez3

1. PH. D. Ciencias Económicas y Empresariales, Universidad de Salamanca. <jmprado@usal.es>.

2. PH. D. Ciencias Económicas y Empresariales, Universidad de Salamanca. <lajefa@usal.es>.

3. PH. D. Ciencias Económicas y Empresariales, Universidad de Salamanca. <igallego@usal.es>.

Abstract

New business practices are mainly characteristic of large firms, especially those quoted on the stock market. Listed companies show a higher commitment to corporate social responsibility (CSR) practices because capital markets allow activists to become a firms socially oriented shareholders. These actors, although small in number, have a significant influence over other larger block-holders. Recent decades have witnessed a significant increase in societal pressure to control the behavior of companies owing to the risks deriving from the economic, social and environmental effects of their business activity. The aim of this work is to test the effect that CSR activist shareholders have on the decision to disclose corporate social responsibility information in the Spanish context, controlling for the rest of the dimensions in Ullmanns theoretical framework.

Keywords: Corporate social responsibility reporting, activist shareholder, ownership structure, corporate governance.

Resumen

Las nuevas prácticas empresariales son eminentemente privativas de las grandes firmas, especialmente aquellas listadas en los mercados de valores. Las firmas en mercado muestran un mayor compromiso hacia las prácticas de responsabilidad social corporativa (CSR por sus siglas en inglés) porque los mercados de capital permiten a los activistas convertirse en accionistas de la firma socialmente orientados. Estos actores, aunque pequeños en número, tienen una influencia significativa sobre los grandes accionistas. En décadas recientes se ha observado un aumento importante en la presión social para controlar el comportamiento de las corporaciones debido a los riesgos sociales, económicos y medioambientales causados por los efectos de su actividad empresarial. El propósito de este trabajo es evaluar el efecto que los socios activistas de CSR tienen sobre la decisión de publicar información sobre la responsabilidad social corporativa en el contexto español, controlando por el resto de las dimensiones en el marco teórico de Ullmann.

Palabras claves: información sobre responsabilidad social corporativa, socio activista, estructura de propiedad, gobierno corporativo.

INTRODUCTION

Situations such as growing pollution, the dumping of toxic waste or the use of child labour, among others, have brought about a process of social awareness that has increased the pressure felt by firms regarding certain theoretical ethical limits that should not be breached when doing business. This acceptable ethical threshold has meant that firms not only comply with legal requirements, but also voluntarily tend to adopt environmental improvements in their manufacturing processes, implement environmental management systems and make it easier for their employees to conciliate their work with their personal lives.

In this sense, companies need to perform well and undertake socially desirable actions, including the distribution of economic, social or political benefits to the groups from which they derive their power (Shocker & Sethi, 1973; Alcabés, 2005). Furthermore, as businesses recognize their stakeholders social expectations, the role of corporate social reporting takes on increasing importance as a mechanism through which such duties of accountability may be discharged (Gray, Owen & Adams, 1996; Tran, 2009).

Several authors, such as Liu and Anbumozhi (2009), argue that external stakeholders, particularly the primary ones -shareholders, government and creditors -are the principal actors in the process of corporate social responsibility (CSR) transparency. In this line, a fewer number of papers such as Roberts (1992), Liu and Anbumozhi (2009) and Prado et al. (2009a), using Ullmanns theoretical framework, have analyzed the role of these stakeholders in the process, showing that there is a limited impact of shareholder power on it.

These papers assume that dispersed ownership is directly associated with firmsaccountability practices, although they do not empirically confirm this relationship. Nevertheless, the last paper mentioned provides evidence for the Spanish setting that larger dominant shareholders are more likely to adopt the emission of CSR reports drawn up according to an international standards guide. Prado et al. (2009a) argue that this effect is due to the strong relationship between the reputation of the firm and that of the shareholders.

On the other hand, other authors such as Lee (2009) and Solomon (2006) indicate that firms commitment to CSR reporting is justified by the fact that managers and larger shareholders could be influenced by activist stockholders. In this sense, the aim of this paper is to test the effect that activist shareholders have on the decision to disclose corporate social responsibility information, controlling for the rest of the dimensions proposed by Ullmann. The result obtained shows that activist shareholders have a significant effect on the process of transparency in relation to the triple bottom line of firm behavior.

SHAREHOLDER ACTIVISTS AND SOCIAL DISCLOSURES: RESEARCH HYPOTHESIS

Stakeholder Theory asserts that the reasons behind social information disclosure is that an organizations survival depends on the support of their stakeholders, understanding them as a person or group that can affect or is affected by the achievement of the organizations objectives (Freeman, 1984, p. 46). In this sense, CSR reporting is the mechanism used by corporations to show a firms social performance to the stakeholders (Roberts, 1992).

Resource dependency theory suggests that power accrues to those parties that control the resources required by the organization, thus creating power differentials among stakeholders (Pfeffer, 1981). In this sense, the power of stakeholders is a function of the resources they control that are essential to the corporation (Ullmann, 1985).

At the most fundamental level, ownership stakes controlled by different stakeholder groups accrue power to these groups vis-à-vis the firm and heighten the urgency that the demands of these groups be met (Van der Laan Smith et al., 2005).

Generally, authors have considered that the less the influence of the top shareholders, equivalent to more dispersed ownership, the greater the likelihood that firms will disclose more information (Keim, 1978; Ullmann, 1985; Craswell & Taylor, 1992; Christopher & Hassan, 1996; Frost, 1999); however, this effect has not been empirically tested for CSR information (Roberts, 1992; Liu & Anbumozhi, 2009; Prado et al., 2009a). In contrast, the positive effect of larger dominant shareholders has been confirmed for the Spanish setting (Prado et al., 2009a).

This last effect could be explained by the fact that the shares of listed firms are traded on the public stock exchanges so the door is open to anyone who can afford to purchase a share to become a shareholder and try to influence the firm. This door could be considered the unique access to corporate management for social and environmental activists in order to advance their socially oriented agendas (Lee, 2009).

The potential influence of this type of shareholder, according to Lee (2009), is higher, even though they are small in number, because (i) the voice of activist has a significant potential to influence the opinions of other large shareholders and, moreover, (ii) corporate managers could consider the most vocal group of shareholders in order to avoid losing legitimacy in the eyes of the majority stockholders. In fact, activist shareholders have expanded their demands from the circumscribed realm of shareholder rights to issues of how successors to the CEO are chosen, how much executives are paid, etc. (Davis & Thompson, 1994).

Taking into account these considerations, the following alternative hypothesis is posed:

H1: Céteris páribus, the contents and quality of the corporate social responsibility report are positively affected by the presence of social activists in the firms ownership structure.

METHODOLOGY

Sample

The target population in the study corresponds to the 116 non-financial Spanish firms quoted on the Spanish continuous market. It should be pointed out that the population was selected taking into consideration the criteria of size and stock market listing used in previous studies (Guthrie & Parker, 1990; Hackston & Milne, 1996; Collet & Hrasky, 2005, Gallego, 2006, García-Sánchez, 2008), as well as the fact that they are obliged to deposit information on corporate governance before the Comisión Nacional del Mercado de Valores (National Stock Market Commission). Consultation of their database provided us with reports from 99 firms during 2009, the sample used in the analysis.

Variables

1. Dependent variable: Practices in corporate social reporting

In this study we have adopted the proposal for CSR reports made by Prado et al. (2009a). Thus, firms CSR disclosures have been classified into five issues. They allow us to define five dependent dummy variables that take the value of one to identify the content and quality of CSR Reporting, and 0 otherwise:

-

The firms disclose several items of economic, social and environmental aspects.

-

The CSR report presents an informal format in accordance with stakeholder demands.

-

The CSR information report is adapted to a standard of the most widespread international model, the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI).

-

The information has been verified or audited by an independent entity which guarantees its accuracy and credibility.

-

The reports compliance with the demands of the GRI has been certified on the part of the organization responsible.

These five original variables were summarized and a principal components analysis was estimated to make it possible to simplify the dependent variables previously considered into components that reflect the underlying common dimensions.

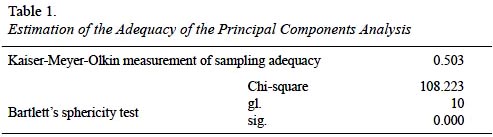

Prior to estimation of the principal components analysis, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measurement of sampling adequacy and Bartletts sphericity test were run. The results obtained show an adequate basis for the empirical examination of factor analysis sufficiency. Table 1 shows how the sufficiency measurement of the general sampling falls within the range of acceptance, as well as the significance of Bartletts sphericity test.

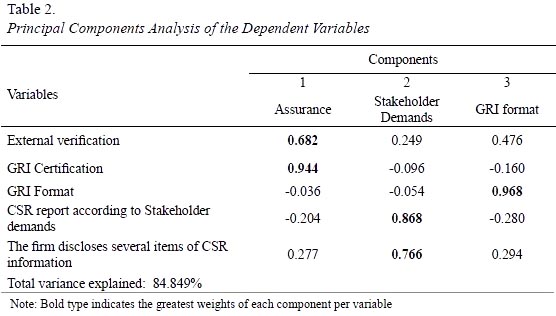

Subsequently, principal components analysis (VARIMAX rotation) was run, and the results are given in Table 2.

By analyzing the loadings, it can be seen that Component 1, ASSURANCE, represents CSR reporting where the information has been verified by an independent entity and the contents and format certified as In Accordance by the GRI.

Component 2, STAKEHOLDER DEMANDS, identifies those firms that give out information on economic and social, and/or environmental matters, in an informal format according to their stakeholder demands.

Finally, the last component, GRI FORMAT, includes CSR reporting in which the contents and format meet the requirements and demands of the GRI, but have not been certified. The disclosing of information in accordance with this model would entail an increase in the contents, quality and objectivity of the information.

2. Independent Variable: Active Shareholders

In order to represent active shareholders, we have used the ratio number of directors that represent active shareholders interests divided by the directors on the board.

3. Control Variables.

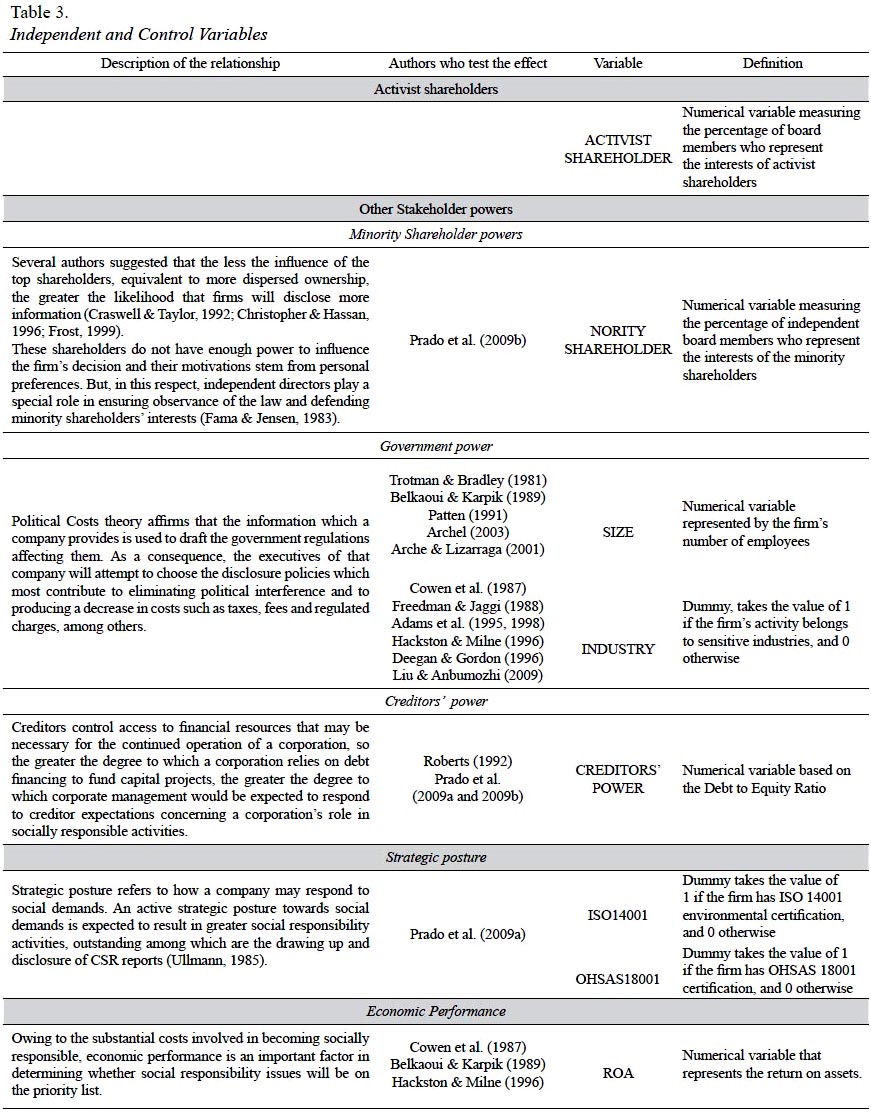

The control variables proposed in this paper are based on the theoretical foundations proposed by Ullmann (1985), which have been tested by Roberts (1992) and Prado et al. (2009a).

Ullmann defined a conceptual framework for the factors explaining social disclosure based on three dimensions: Stakeholder power, Strategic posture and Economic performance.

-

Stakeholder Power reflects the theoretical basis of the cited framework since the firm, when stake-holders control resources critical to the organization, is likely to respond in a way that satisfies the demands of the stakeholders.

-

Strategic Posture describes the mode of response of an organizations key decision-makers toward demands. An active posture implies a position in which managers seek to influence their organizations relationship with important stakeholders in order to achieve optimal levels of interdependence.

-

Economic Performance is important in two ways: (i) it determines the relative weight of social demand and the attention it receives; for instance, in periods of high profitability, social demand receives more attention; and (ii) it influences the financial capability to undertake costly programs related to social demands.

The independent and control variables are summarized in Table 3.

Analysis Model

Testing hypotheses H1 entails analyzing the effect of the power of the active stockholders on the characteristics and contents of the CSR report, which have been synthesized in three components through factor analysis. Dependence models or multiple linear regression models are used for this purpose.

With that goal in mind, we propose the following model [1], in which the CSR report characteristics are a function of activist shareholders and several variables that represent the dimensions of Ullmanns framework.

CSRreport = f (Active shareholder power, Other stakeholder power, Strategic posture, Economic performance) [1]

Model [1] can be empirically estimated by using the equation [2]:

CSRreporti = β0 + β1ActShaPoweri + ∑i4βiOtherStkPoweri + ∑i2βiStratePosturei + β8EcoPerfori + ε [2]

In which:

ActShaPoweri is the independent variable that identifies the power of active shareholders on company i, measured by the number of directors that represent socially active stockholders.

OtherStkPoweri are control variables that identify the power of other stakeholders on company i, measured by the variables: INDEPENDENT, SIZE, INDUSTRY and LEVERAGE.

StratePosturei are control variables that identify the environmental and social strategic posture of company i, measured by the variables: ISO14001 and OHSAS18001.

EcoPerfori is a control variable that identifies the economic performance of company i, measured by ROA.

RESULTS OF THE ANALYSIS

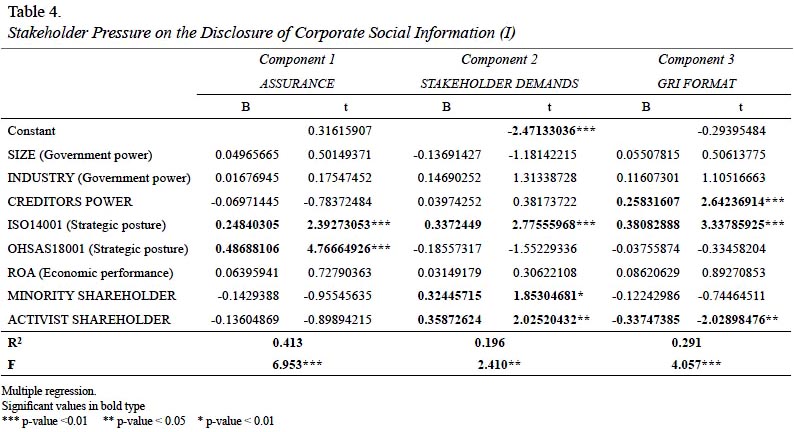

The results obtained by the estimation of all of the dependence models proposed are synthesized in Table 4.

Model 1, which analyzed the effect of active shareholder power on CSR report assurance, has an explanatory power of 41.30% for a confidence level of 99% (p-value < 0.01).

On analyzing the variables individually, it can be seen that the independent variable proposed, which represents the pressures exerted by active shareholders, does not affect the external assurance of the CSR report.

Regarding the control variables, those relating to the firms strategic posture on presence/absence of ISO14001 and OHSAS18001 certification have a positive effect at a confidence level of 99% in the model relating to Component 1 –ASSURANCE.

The variables SIZE, INDUSTRY and ROA have a positive effect on assurance, but this impact is statistically insignificant, whereas CREDITORS PRESSURE has a negative insignificant effect on the dependent variable.

Model 2, which analyzed the effect of active share holder power on CSR report format according to a firms stakeholder demands, has an explanatory power of 19.60%, for a confidence level of 95% (0.01 < p-value < 0.05). The pressure exerted by active shareholders has a positive effect on this CSR report typology for a confidence level of 95%.

Regarding the control variables, the presence/absence of ISO14001 and the pressure exerted by minority shareholders have a positive effect at confidence levels of 95% and 90% (0.05 < p-value < 0.1), respectively, in the model relating to Component 2.

The variables INDUSTRY, CREDITORS PRESSURE and ROA have a positive effect on assurance, but this impact is statistically insignificant. On the other side, SIZE and OHSAS18001 have a negative insignificant effect on the dependent variable.

Model 3, which analyzed the effect of active shareholder power on CSR reporting according to the GRI format, has an explanatory power of 29.10% for a confidence level of 99%.

The independent variable proposed has a negative effect on Component 3-GRI FORMAT for a confidence level of 95%. In contrast, two control variables, CREDITORS PRESSURES and ISO14001, have a positive effect on it for a confidence level of 99%.

The variables SIZE, INDUSTRY, ROA, OHSAS 18001 and MINORITYSHAREHOLDER PRESSURES have an insignificant positive effect on Component 3, except the two last variables, for which the effect is negative.

The overall analysis of the results obtained allows us to partially accept the hypothesis proposed since activist shareholder pressure has a contradictory effect on CSR disclosure practices. On the one hand, these stakeholders encourage the process of drawing up a report that satisfies the firms stakeholder demands in the form of a GRI format that is highly general. However, on the other hand, these actors are not interested in the external verification of the information disclosed.

DISCUSSION OF RESULTS

The empirical evidence of the present paper indicates that activist shareholders play an important role in a firms decision to disclose CSR information. Specifically, we have observed that the directors who represent this type of shareholder are very interested in having firms make available to their stakeholders the information they consider most suitable to their needs. In certain aspects, these demands for information are negatively related to the adoption of internationally accepted guidelines, such as those proposed by the GRI. In this sense, Logsdon and Van Buren (2008) have shown that the majority of activists actions deal with specific issues that affect specific groups.

Moreover, through direct comparison with the results obtained by García-Sánchez, Gallego-Álvarez and Prado-Lorenzo (2008) and Prado et al. (2009a), our results show that stakeholder influence, particularly government power, is not the driver of CSR disclosure. This contrast effect allows us to state that firms disclose information orientated to satisfying their stakeholders demands and not in order to reduce political costs.

On the other hand, and in line with the results obtained by Prado et al. (2009a), the adoption of this international standard and the verification of the information disclosed is strongly linked to the strategic posture a firm has adopted regarding the social and environmental aspects of its behavior, particularly with respect to the latter. This relationship cannot be extended to the economic dimension of the corporations activity. We have therefore concluded that firms disclosure practices are a trade-off between activist demands and the social and environmental strategic plan designed by managers.

CONCLUSIONS AND LIMITATIONS

In this study we posited a dependence model in an attempt to analyze the effect that activist shareholders have on a firms decision to disclose information on corporate social responsibility in the Spanish context, controlled by the dimensions proposed by Ullmann. In the model posed, the dependent variables are grouped into three components: Component 1, ASSURANCE, which represents the guarantee of the CSR report when the information has been verified by an independent body and the contents and format are certified as In Accordance with the GRI. Component 2, STAKE HOLDER DEMANDS, identifies the firms that provide information on economic, social and/or environmental aspects in an informal format in accordance with the demands of their stakeholders. Component 3, GRI FORMAT, includes CSR reports in which the contents and format comply with GRI requirements and demands, but have not been verified.

The independent variable is represented by the activist shareholders, and is obtained by the ratio of the number of directors representing the interests of the activist shareholders divided by the number of directors on the Board. The control variables in this research are based on the theoretical framework proposed by Ullmann (1985), and are the factors that explain the disclosure of social information on three levels: power of the stakeholders, strategic posture of the firm and economic performance. The results obtained show that activist shareholders have a significant effect on the process of transparency related to the triple bottom line (economic, social and environmental information) of firm behavior. These results should be compared with those obtained for firms of other countries, with a different economic environment and in a different time frame, as possibilities for future research.

REFERENCES

Adams, C. A. (2002). Internal Organisational Factors Influencing Corporate Social and Ethical Reporting. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability, 15(2), 223-250.

Adams, C. A., Hill, W. Y., & Roberts, C. B. (1995). Environmental Employee and Ethical Reporting in Europe. ACCA Research Report 41. London: Chartered Association of Certified Accountants.

Adams, C. A., Hill, W. Y., & Roberts, C. B. (1998). Corporate Social Reporting Practices in Western Europe: Legitimating corporate behaviour? British Accounting Review, 30 (1), 1-21.

Alcabés, N. (2005). La empresa socialmente responsable: Una propuesta de autoevaluación. Cuadernos de Difusión, 18-19 (10), 155-161.

Archel, P. (2003). La divulgación de la información social y medioambiental en la gran empresa española en el período 1994-1998: Situación actual y perspectivas. Revista Española de Financiación y Contabilidad, XXXII(117), 571-601.

Archel, P., & Lizarraga, F. (2001). Algunos determinantes de la información medioambiental divulgada por las empresas españolas cotizadas. Revista de Contabilidad, 44 (7), 129-153.

Belkaoui, A., & Karpik, P. G. (1989). Determinants of the Corporate Decision to Disclose Social Information. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 2 (1), 36-51.

Christopher, T., & Hassan, S. (1996). Determinants of Voluntary Cash Flow Reporting: Australian Evidence. Accounting Research Journal, 19, 113-124.

Craswell,A.T.,&Taylor,S.L.(1992).DiscretionaryDisclosure by Oil and Gas Companies: An Economic Analysis. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, 19, 296-308.

Collett, P., & Hrasky, S. (2005). Voluntary Disclosure of Corporate Governance Practices by Listed Australian Companies. Corporate Governance. An International Review, 13(2), 188-196.

Corporate Social Disclosure Practice: A Comparative International Analysis. (1990) Advances in Public Interest Accounting, 3, 159-175.

Cowen, S., Ferreri, L., & Parker, L. D. (1987). The Impact of Corporate Characteristics on Social Responsibility Disclosure: A Typology and Frequency-based Analysis. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 12(2), 111-122.

Davis, G. F., & Thompson, T. A. (1994). A Social Movement Perspective on Corporate Control. Administrative Science Quarterly, 39(1), 141-173.

Deegan, C., & Gordon, B. (1996). A Study of the Environmental Disclosure Practices of Australian Corporations. Accounting and Business Research, 26(3), 187-199.

Fama, E., & Jensen, M. (1983). Separation of Ownership and Control. Journal of Law and Economics, 26, 301-326.

Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic Management. A Stakeholder Approach. Marshfield, MA: Pitman.

Freedman, M., & Jaggi, B. (1988). An Analysis of the Association between Pollution Disclosure and Economic Performance. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 1(2), 43-58.

Frost, G. R. (1999). Environmental Reporting: An Analysis of Company Annual Reports of the Australian Extractive Industries 1985-1994. (Doctoral Thesis). Portland, ME: University of New England.

Gallego I. (2006). The Use of Economic, Social and Environmental Indicators as a Measure of Sustainable Development in Spain. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 13, 78–97.

García-Sánchez, I. M. (2008). Corporate Social Reporting: Segmentation and Characterization of Spanish Companies. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 15, 187-198.

García-Sánchez, I. M., Gallego-Álvarez, I., & Prado-Lorenzo, J. M. (2008). The Divulgation of Information on Corporate Social Responsibility Viewed through the

Theory of Political Costs. In Corporate Social Responsibility. New York: New Science Publishers.

Gray, R. H., Owen, D. L., & Adams, C. (1996). Accounting and Accountability: Changes and Challenges in Corporate Social and Environmental Reporting. Hemel Hempstead, UK: Prentice Hall.

Guthrie, J., & Parker, L. D. (1989). Corporate Social Reporting; A Rebuttal of Legitimacy Theory. Accounting and Business Research, 19 (76), 343-352.

Hackston, D., & Milne, M. J. (1996). Some Determinants of Social and Environmental Disclosures in New Zealand Companies. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 9(1), 77-108.

Keim, G. (1978). Managerial Behaviour and the Social Responsibilities Debate: Goals versus Constraints. Academy of Management Journal, 57-68.

Lee, M-D. P. (2009). Does Ownership Form Matter for Corporate Social Responsibility? A Longitudinal Comparison of Environmental Performance between Public, Private and Joint-venture Firms. Business and Society Review, 114(4), 435-456.

Liu, X., & Anbumozhi, V. (2009). Determinant Factors of Corporate Environmental Information Disclosure: An Empirical Study of Chinese Listed Companies. Journal of Cleaner Production, 17, 593-600.

Logsdon, J. M., & Van Buren, H. J. (2008). Justice and Large Corporations: What do Activist Shareholders Want? Business and Society, 47(4), 523-553.

Milne, M. J., & Adler, R. W. (1999). Exploring the Reliability of Social and Environmental Disclosures Content Analysis. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 12(2), 237-256.

Pfeffer, J. (1981). Power in Organizations. Marshfield, MA: Pitman.

Prado, J. M., Gallego, I., & García, I. (2009a). Stakeholder Engagement and Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting: The Ownership Structure Effect. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 16, 94-107.

Prado, J. M., García, I., & Gallego, I. (2009b). Características del consejo de administración e información en materia de responsabilidad social corporativa. Revista Española de Financiación y Contabilidad, 38(141), 107-135.

Qu, R. (2007). Effects of Government Regulations, Market Orientation and Ownership Structure on Corporate Social Responsibility in China: An Empirical Study. International Journal of Management, 24(3), 582-591.

Roberts, R. W. (1992). Determinants of Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure: An Application of Stakeholder Theory. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 17(6), 595-612.

Solomon, J. F. (2006). Private Social, Ethical and Environmental Disclosure. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 19(4), 564-591.

Shocker, A. D., & Sethi, S. P. (1973). An Approach to Incorporating Social Preferences in Developing Action Strategies. California Management Review, Summer, 97-105.

Tran, B. (2009). Green Management: The Reality of Being Green in Business. Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Science, 14(27), 21-45.

Trotman, K. T., & Bradley, G. W. (1981). Associations between Social Responsibility Disclosure and Characteristics of Companies. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 6(4), 355-362.

Ullmann, A. A. (1985). Data in Search of a Theory: A Critical Examination of the Relationships among Social Performance, Social Disclosure, and Economic Performance of U.S. Firms. The Academy of Management Review, 10(3), 540-557.

Van der Laan Smith, J., Adhikari, A., & Tondkar, R. H. (2005). Exploring Differences in Social Disclosures Internationally: A Stakeholder Perspective. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 24(2), 123-151.

Received: September 13, 2011

Accepted: February 21, 2012