Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Science

versión impresa ISSN 2077-1886

Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Science vol.23 no.45 Lima jul./dic. 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/JEFAS-01-2018-0018

ARTICLE

Social power of preadolescent childrenon influence in their mothers’ purchasing behavior. Initial study in Peruvian toy stores

Miriam Carrillo and Alicia Gonzalez-Sparks*

Nestor U. Salcedo**

Marketing, Universidad ESAN, Lima, Peru, and*

Informatión Technology and Quantitative Methods, Graduate School of Business, Universidad ESAN, Lima, Peru**

Abstract

Purpose – This paper aims to investigate the relatiónship between legitimate and expert social power types of preadolescent childrenon the influence perceptión in their mothers’ purchasing behavior in Peruvian toy stores. The literature review takes into consideratión the concepts of social power and the influenceon family behavior to then focuson social power within family behavior with the purpose of mainly developing four hypotheses regarding purchasing behavior.

Design/methodology/approach – The methodology followed a non-experimental transversal correlatiónal-causal design. A pilot sample size of 67 cases was used. The sample was basedon an objective populatión of Peruvian mothers of families that live in northern Lima and that go to purchase toys to major shopping centers with their children aged 8-11 years.

Findings – The results show that the expert social power, as well as the legitimate social power, has a strong relatiónship. In additión, both social powers have an impacton the influence perceptión in purchasing child-mother, but noton the influence perceptión in purchasing mother-child. Moreover, the test of moderatión of the expenditure levelon toy purchases did not have an effecton the context that was studied.

Originality/value – The contributión shows that important changes are happening in the consumptión behavioron the aspect of children influencing mothers, and that for Latin American contexts, the level of expenditure still does not crucially affect the causality demonstrated.

Keywords Expert social power, Influence in purchasing behavior, Legitimate social power, Peruvian toy stores

Paper type Research paper

Introductión

Children should be seen as three markets inone (Aldea and Brandabur, 2012; McNeal, 1999); the actual market that spends moneyon their desires, the potential market for the majority of goods and services and an influence market that motivates their parents to consume different stuff. Children notonly learn by copying their parents’ consumptión behavior (Turner et al., 2006) but also apply pressure in the opposite directión; they influence their parents’ final purchasing decisión behavior in three basic categories: toys, clothes and food (Nicholls and Cullen, 2004). Specifically, mothers are more likely to impulsively buy toys, clothing and sweets for children (Turccínková et al., 2012).

Likewise, the socializatión of the consumer as "processes through which young people acquire abilities, knowledge, and relevant attitudes for their functióning as consumers in the marketplace" (Ward, 1972) leads to many children developing their own opinión and likes over the products that they want to buy (Turner et al., 2006).

Alonso and Grande (2013) argue that children influence purchasing in two manners. They induce the consumptión of goods specific for them. In additión, we conditión the purchases of goods in which children participate as consumers together with adults. They are able to influence the purchases because they remember the existence of the products and act as prescribers. Furthermore, it is said that children influence the purchase because they retain the product advertising messages better than their parents. Thus, in this way, they can motivate the product purchasing. "It has been confirmed that the qualitative compositión of the basket of goods is different when it is done in the presence of children at the point of sales" (Alonso and Grande, 2013).

Research has found that children have power over their parents in family consumptión decisións. McNeal (1999) estimates that children between ages of 4 and 12 influenceon approximately US$188,000 annuallyon purchases related to the family in the USA. While in Peru, as per a study undertaken by the consulting company CCR for El Comercio (2014), children influenceon the purchase of 62 per cent of Lima households. The toy market moves approximately between US$75 and 80m (Andina, 2010). Consequently, the influence of childrenon the family consumptión decisións is a topic that merits attentión.

Being so, what is the relatiónship between the legitimate social power (LSP) and expert social power (ESP) types of childrenon the influence perceptión of their mothers in Peruvian toy stores? This paper concentrateson Peruvian mothers living in the city of Lima, who have and live with their children who are in the preadolescent stage of development, meaning between 8 and 11 years. Mothers were selected for this research for two main reasons. First, mothers are more often the receptors of influence attempts than fathers (Cowan and Avants, 1988; Cowan et al., 1984). Second, mothers are usually the agents for family purchases and are considered to be better familiarized with the purchase influence attempt of their children.

For methodological purposes, the last studied relatiónship regarding passive social power of childrenon influence from the mothers’ perspective (Flurry and Burns, 2005) was used. To assess these variables, we applied instruments already validated by their authors and which have been used in other studies.

For these reasons, discussións in this field suggest extending this investigatión (Flurry and Burns, 2005; Goodrich and Mangleburg, 2010): first, validating the veracity of the proposed constructs (Flurry and Burns, 2005); second, taking other populatións as emerging markets; and third, considering the effect of social power at stages of influence in purchasing (Goodrich and Mangleburg, 2010).

Social power

Weber (1962) defines social power as "the probability that an actor within a social relatiónship is in the positión of doing as he wills not withstanding resistance, independently over the basison which this probability stands". Likewise, Cartwright (1959), after taking Lewinian’s theory (Lewin, 1951), established the definitión of power as "the inductión of forces by entity B over A and another to the resistance of this inductión created by A". Therefore, in accordance with this conceptualizatión, it is the degree to which agent B has control over A’s behavior dependingon the magnitude of force that B can exert over A and over A’s resistance.

The theorists of social power of the 1950’s and 1960’s have differed over the diverse aspects of the conceptualizatión of social power. However, Smith (1970) says that these theorists agree in two basic concepts of the definitión. First, social power is the potential ofone person to exert a force toward change in another person. Second, social power is not simply basedonone quality or qualities that the powerful person possesses rather by complex conditións that rule the interdependence of the persons in a social relatiónship. Additiónally, Elias (2008) mentións that since the study by French and Raven (1959), power is quantified in the capacity of a power possessor to persuade an identified objective, being the maximum influence possible that he or she can exert.

French’s (1956) taxonomy is composed of five types of power: reward, coercive, legitimate, expert and referent. The firstone, reward, is "basedon the perceptión of A, where B has the ability to mediate rewards for A". The coercive power is "basedon the perceptión of A, where B has the ability to mediate punishments for A". The legitimate power is "basedon A’s perceptión where B has a legitimate right of prescribing the behavior for A". The expert power is "basedon A’s perceptión, where B has a special knowledge or expertise". Finally, the referent power is "basedon the identificatión of A with B". Then, this included a sixth power: informatiónal or persuasión (Raven, 1993).

Social power in family behavior

The previously explained theory also considers the fathers and the children in a relatiónship of interdependence with a different level of power. When there is a conflict between the children and the parents’ perspective with respect to a consumptión decisión, for example, the possibility of purchasing a product, what brand to buy, how much to buy, among others, the children could strategically use their power to persuade the parents, thus gaining influence in the decisión-making process (Cowan and Avants, 1988; Cowan et al., 1984; Kim et al., 1991).

As per Flurry and Burns (2005), the theory of social power suggests that the five bases can be used in family behavior in two ways: active and passive. Using power to influence is commonly considered active, although sometimes it can be passive, like when the mere presence of the power is influential (Podsakoff and Schriesheim, 1985; French and Raven, 1959). Both forms of power, active and passive, contribute to the potential of a person to achieve a result in accordance to his or her own reference. Hence, Flurry and Burns (2005) and Williams and Burns (2000) argue that children exercise influence through active social power and/or passive social power.

When there is no evidence of spoken words or manifested actións by the child, it is said that the exerted influence by him or her can also be passive. Consequently, the passive sources of poweronly need to be possessed to have an effect (Corfman and Lehman, 1987). Then, for a child, a source of power is passive if his or her parent infers its presence and acts upon it instead of upon any actión by the child. This is known as child’sinfluenceon the parents or the parent perceptións of the child’s undeclared preferences (Wells, 1965). As these children grow, they influence family purchasing decisións in a more passive manner, as the parents learn the likes and dislikes of their children and make buying decisións basedon that (Roedder, 1999).

Being so, when talking about expert power, this means providing knowledge and superior ability to the influenced person, for which the child can possess more knowledge in determined categories of products such as clothing and toys, among others (Flurry and Burns, 2005).on the other hand, when talking about legitimate power,one perceives the right to control the opinión or behavior of the other person (Flurry and Burns, 2005). This power is derived from a justifiable right (Elias, 2008). A child has legitimate power when he perceives that he has the right to make a decisión basedon his or her interests. Being so, the following hypothesis arises:

H1. There exists a direct positive relatiónship between passive expert social power and passive legitimate social power of preadolescent children as mothers’ perceptión in the toy stores context.

Influence in family purchasing behavior

While social power is "the potential influence ofone person over anotherone" (Cartwright and Zander, 1968; Cartwright, 1965), Swasy (1979) defines the influence as a change in cognitión, attitude, behavior or the emotión of a person.

Influence is defined as the use of power to achieve a result (Coleman, 1973). At the same time, influence couldonly be attained as a result of a reciprocal exchange process between two or more parties (Sprey, 1975). Olson et al. (1975) claim that the use of power exerts an influence known as "circular causal process", for which the resulted power in any of the parts is a fusión of all perspectives of the parts involved in the decisión-making process.

Flurry and Burns (2005), quoting Olson et al. (1975), say that given the reciprocal nature of the influence, if measuring the influence is wanted, it is necessary to measure the perspectives of all the significant members of the decisión-making process. Also, French and Raven (1959) say that it is to be expected that the perceptións of the parts will be similar but not identical. That is why, it is important to consider that in the families that face a social power that could be exerted by a child, the mother could very well influenceon its decisión. For this reason, the following is considered as the second hypothesis:

H2. The passive social power, expert and legitimate of preadolescent children have a direct effecton mother’s perceptión of the child’sinfluence (from mother to child) in a toy purchase.

However, demographical and structural changes in the households have changed children’s roles in families’ buying activities, increasing both their participatión in family decisiónmaking processes and their purchasing power (Flurry and Burns, 2005; Williams and Burns, 2000). In the present time, in many societies, both parents work. Therefore, Sellers (1989) states that the parents, with time limitatións to go shopping, permit or even encourage their children to participate in the process of making decisións.

Wimalasiri (2000) says that influence is a term used to describe the interactión between the parents and their children. But, at the same time, influence happens when the child tries to change the thoughts, feelings or behaviors of the parent. Children constitute a large secondary market that influences the family purchase (McNeal, 1988). Research has concluded that children tend to influence moreon the purchasing decisións of products that directly relate to them or that even affect them (Arzu, 2011; Sener, 2011; Foxman et al., 1989b; Atkin, 1978). Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3. The passive social power, expert and legitimate of preadolescent children have a direct positive effecton mother’s perceptión of the child’sinfluence (from child to mother) in toy stores.

On the other hand, it has been found that children have a lesser degree of influence in the decisións regarding products that have high costs and that are used by all the family (Foxman et al., 1989a). At the age of eight, most children become socialized consumers and enjoy having discretión to spend their own money (McNeal, 1992a, 1992b; Isler et al., 1987). Basedon this, the fourth hypothesis arises:

H4. The direct positive effect of the passive social power, expert and legitimate of preadolescent childrenon mother’s perceptión of the child’sinfluence (from child to mother) is moderate negatively for the purchase amount in the toy stores.

Methodology

The research undertaken has a non-experimental transversal correlatiónal design. It is non-experimental given the fact that the unit is observed in its reality, meaning that the behaviors of the independent variables studied have already occurred, reason for which they have not been or could not have been manipulated. In additión, it is a transversal study because the data collectión was done at a determined moment in time. Finally, it is correlatiónal because it describes the relatiónship that exists between LSP and ESP types and the influenceon the mothers’ purchasing behavior.

Sample

The target populatión for this study was mothers of Peruvian families who reside in Lima and go to purchase toys with their preadolescent children to major shopping centers.

The sampling method is probabilistic by clusters, where the units of analysis are encapsulated in various physical locatións. Among all the possible clusters, toy stores of northern Lima shopping centers were chosen where the units of analysis were found – mothers with kids aged 8-11 years.

The Natiónal Institute for Statistics and informatión, Instituto Naciónal de Estadística eInformática, indicates that the Peruvian populatión reached 31,151,643 inhabitants (INEI, 2015b). Considering that,on average, there are four members per household (Ipsos Perú, 2015), where Peruvian women have an average of 2.6 children (Andina, 2013; INEI, 2015a), and the populatión of preadolescent children between 6 and 11 years of age is 942,000 (INEI, 2015c).

Moreover, it was evidenced that the populatión of Metropolitan Lima is of 9,752,000 inhabitants, of which more than half of them live in East and North Lima (INEI, 2015c). North Lima is represented by 25.5 per cent of the total populatión of Metropolitan Lima, where the predominant socio-economic levels are C (39.6 per cent) and D (37.7 per cent), with San Martin de Porres and Comas being the districts with larger populatións.

Because of the fact that this is a preliminary research, a pilot sample of 50 participants was chosen with the purpose of testing the research model.

Measurements

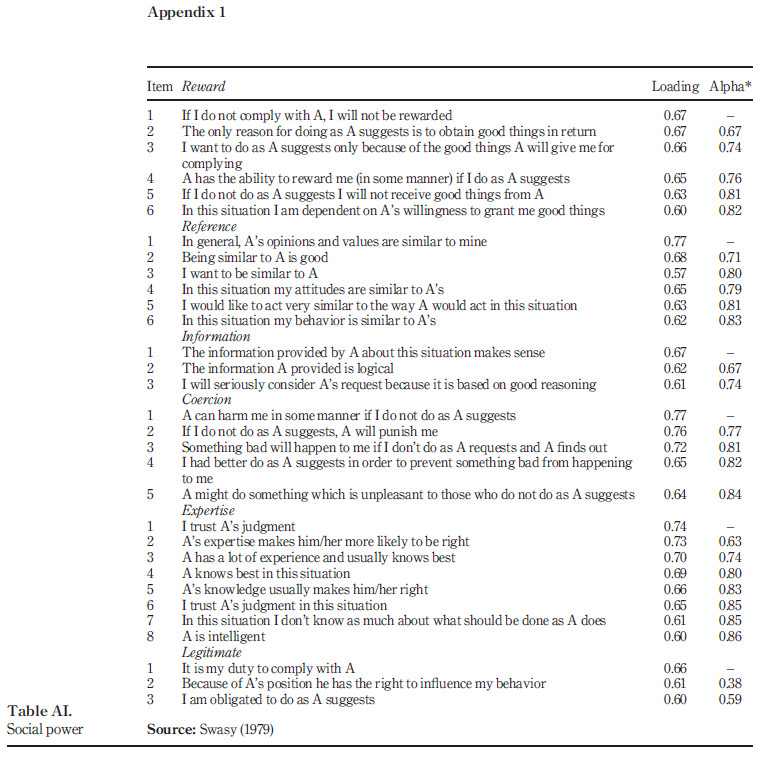

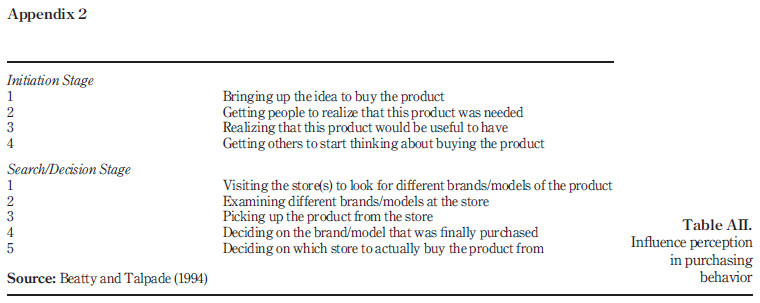

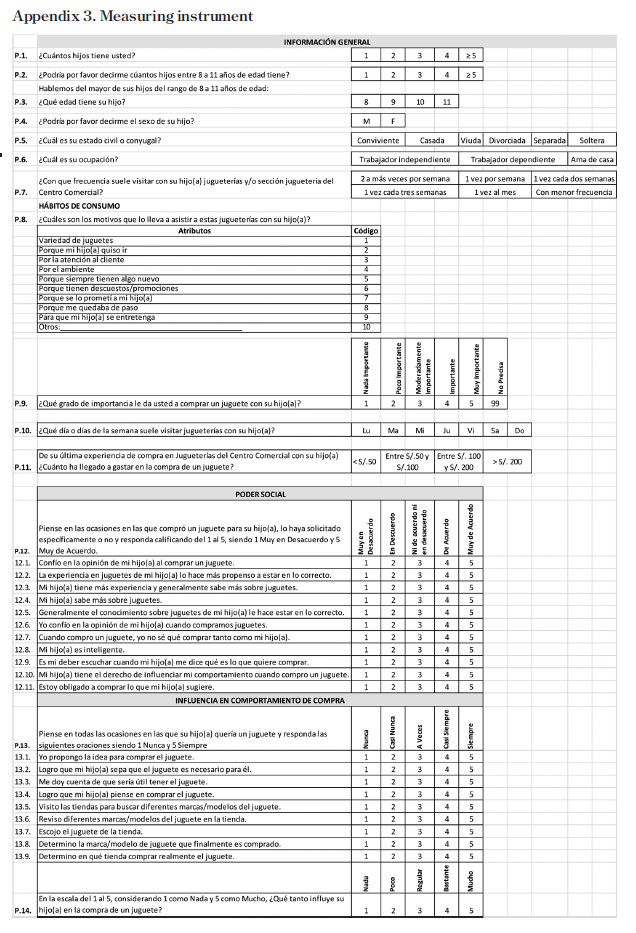

To elaborate the questiónnaire, the scales of Swasy (1979) and from Beatty and Talpade (1994) were used as the basis (Appendix 1 and Appendix 2). These were adapted for the purpose and context of this research project (Appendix 3). The measuring instrument for social power is basedon adaptatións of Swasy (1979) of scales used to measure the perceptión of mothers according to the two types of passive social power selected: legitimate and expert. For the measurement of the mother’s perceptión of influence, an adaptatión of Beatty and Talpade (1994) was used, which are two scales of relative influence;one basedon the initiatión stage and the otheron the initial search/decisión stage. All this is summed up in a questiónnaire that consists of closed questións, which are the filter questións, with a Likert scale from 1 to 5.

The instruments for constructs and items used in this study have been previously validated by the authors of said concepts for social power and influence in purchasing. Initially, we recognized 85 from 150 items (French and Raven, 1959), thus we selected 31 validated items (Swasy, 1979), consideringonly the dimensións of ESP (8 items) and LSP (3 items).on the other hand, we recognized 9 validated items from 26 items (Beatty and Talpade, 1994) considering the dimensións of initial influence in purchasing – IIP (4 items) and decisiónal influence in purchasing – DIP (5 items) for the stages of influence in purchasing to get the final scale. The items, originally in English, were translated by a specialist and revised by three bilingual university professors in marketing field.

Passive social power (ESP and LSP), in accordance with Flurry and Burns (2005), is the degree to which a person is perceived to have the right to exert influence or the right that a person has of influencingon the behavior and/or beliefs of the other person. This variable will be measured through a basic Likert scale of five points, instrument elaborated and validated by Swasy (1979), which was adapted for the purpose of this study.

Influence perceptión in purchasing behavior (initial influence in purchasing – IIP – and decisiónal influence in purchasing – DIP). Influence perceptión is defined as the use of power to achieve a result (Coleman, 1973), in this situatión, the purchase. In turn, by definitión, the influence couldonly be achieved as a result of a process of exchange between two or more parts (Sprey, 1975). For this case, it will be the influence perceptión in mothers’ purchasing behavior, from mother to child. This variable will be measured over a frequency range of a five-point Likert instrument developed and validated by Beatty and Talpade (1994), which will be adapted for the study.

In additión, there is the variable of influence perceptión in mothers’ purchasing behavior, from child to mother, to purchase of a toy (INFL). For this variable, a Likert scale of 1-5 was used so that the results could be crossed with the other two scales previously described.

Control variables

Apart from the central variables to measure, various papers present other variables. The authors recommend considering and evaluating them to know the context upon which the central variables are given. These control variables are demographic variables: child age, child gender and expenditure level (purchase amount) per toy. This last control variable is used as a dummy variable used to measure moderatión in two moments, lower or higher than S/.100.00 (dummy purchasing 100 – DP100), according to the average in spending from this sample.

Procedure

SPSS software was used to process the data. This way, a parametric analysis of the variables of social power with the influence in purchasing to establish the degree and directión (positive or negative) of the relatiónship was possible.

In the first place, to determine passive social power and influence in purchasing, a correlatión analysis and a factor analysis was performed to reduce the number of variables, in additión to verifying that the items related to the described dimensións by the authors. That followed the stages of the procedure described by Hair et al. (2014).

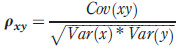

So as to verify the degree of the relatiónship of the values of the variables, the Pearson coefficient of correlatión was applied; this to done to determine the linear dependency between the two variables. The mathematical expressión of the said coefficient takes into account the covariance and the variance of the two variables, which is expressed as follows:

The values that Ρxy can have are in the range of [-1,1], so there is no correlatión between the variables if Ρxy = 0, while the correlatión will be perfectly positive Ρxy = 1 or perfectly negative if Ρxy = -1.

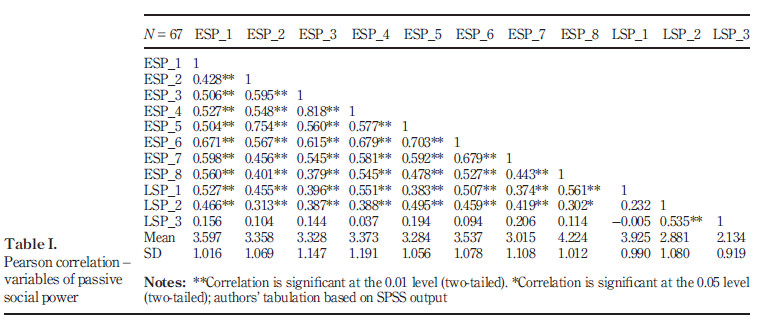

For the analysis of passive social power, Table I shows that the correlatións are significant among the items that correspond to ESP and LSP as independent factors. Both the studied dimensións of passive social power correlate according the bilateral significance with the majority of the items.only the item LSP_1 has no correlatión with the items LSP_2 and LSP_3.

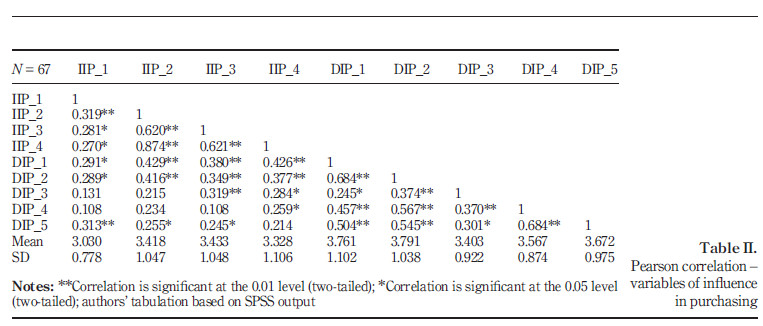

Likewise, with respect to the influence in purchasing, Table II shows that the correlatións are significant among the items that correspond to the factors of IIP and DIP.only lower correlatión indexes are reflected in IIP_1 and DIP_3 for their peers.

Subsequently, according to the factorial tests, the KMO and the Barlett tests, which is basedon whether the contrasts among the partial correlatións of the variables are sufficiently small, it can be said that a relatiónship among these variables exists. Having obtained a KMO index = 0.893 > 0.500 for passive social power and KMO index = 0.763 >0.500 for influence in purchasing, the factorial analyses can be applied; and at the same time, the variables are grouped for data interpretatión.

The Barlett’s sphericity test proves the null hypothesis that the correlatións matrix is equal to the identity matrix. Then, being the identity matrix different to the correlatións’one, this allows the performance of factorial analysis. As the levels of sig. = 0.00 < 0.05, the factor analyses are possible.

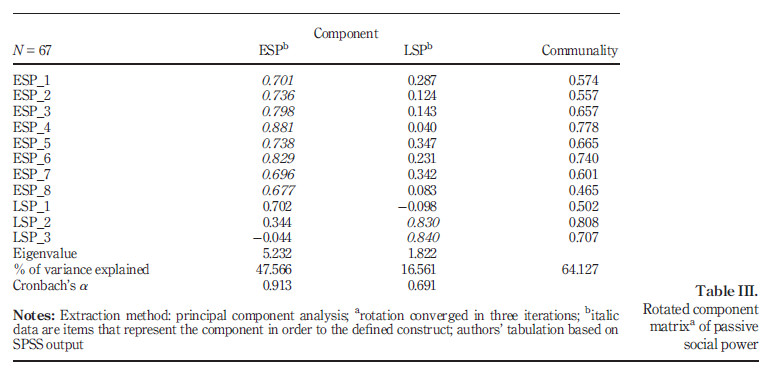

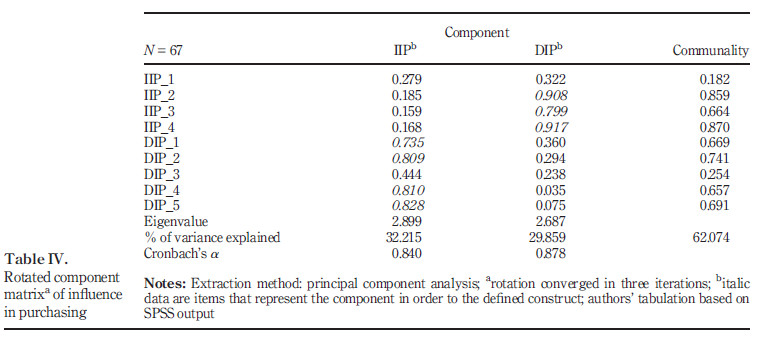

Later, in accordance to the total variance resulting from the data, for the passive social power, two self-values were determined that explain 64.127 per cent of the total variance of the original data (Table III). As for the influence in purchasing, two self-values were determined that help explain 62.074 per cent of the total variance of the original data (Table IV).

Also, in the rotated component matrixes, Tables III and IV, the factors of ESP (8 items) and LSP (3 items) from a total of 11 items of passive social power, as well as the factors of IIP (4 items) and DIP (5 items) from a total of 9 items of influence in purchasing, were generated.

According to the results from the procedures and the use standards of factor loadings related to sample size needed (Hair et al., 2014), we used items with factor loading >0.65 and lower communality basedon their dimensión. For these reasons, we did not use the items LSP_1, IIP_1 and DIP_3.

Finally, the Cronbach’s a for each dimensión was estimated, and the results are ESP > 0.913, LSP > 0.691, IIP > 0.840 and DIP > 0.878. Although LSP has a Cronbach’s a < 0.70, this is due to non-use of an item with lower factor loading and theonly use two final items for the dimensión. However, according to Nunally and Bernstein (1994), as a pilot test is acceptable.

Results

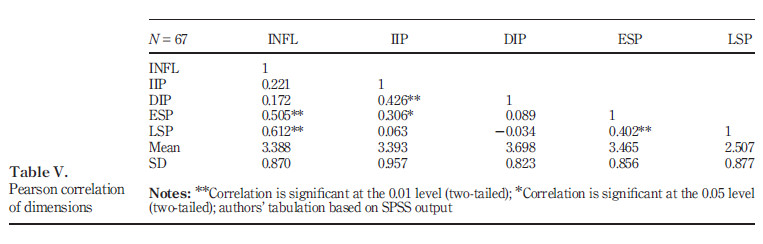

As per the results, Table V shows that the correlatión analysis of the dimensións of ESP and LSP, both passive, present a correlatión of 0.402 with sig. level <0.01, for which H1 is supported. This result supports the evidence of the positive relatiónship of the two passive social powers that the mother perceives with respect to her child in the context of toy stores in an emerging market. That is relevant, as these two passive social powers can be potentially causalon influenceon purchasing behavior by mothers regarding toys.

Nevertheless, both variables present correlatións under 0.5 with regard to the variables of influence in purchasing behavior (mother-child) with level of sig. >0.05;only ESP with IIP presents a correlatión of 0.306 with a level of sig. <0.05. Thus, it demonstrates that there is no complete relatiónship between the said variables, deeming unnecessary the regressión analysis that looks at the causality of said variables. Consequently, H2 is not supported.

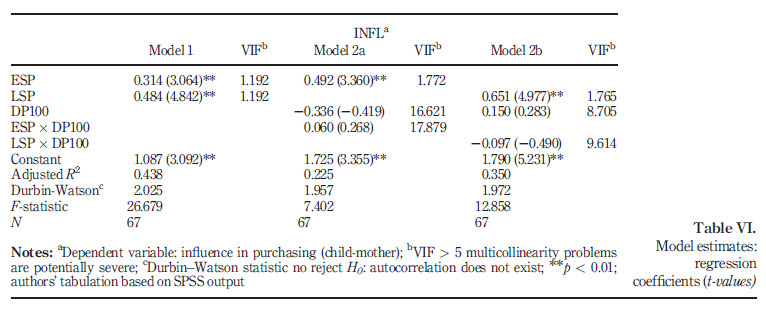

On the other hand, both variables have correlatións higher than 0.5 with regard to the variable of influence in purchasing behavior (child-mother) with levels of sig. <0.01; this demonstrates that there is a relatiónship between ESP and LSP variables with the influence in purchasing behavior from child to mother (INFL). The previous relatiónship, between ESP-LSP with INF, allows a regressión test showed in the Table VI (Model 1). This technique has the purpose of determining the existence of causality between the mentióned variables.

A multiple linear regressión was calculated to predict influence in mothers’ purchasing behavior (INFL), from child to mother, basedon ESP and LSP. Looking at the regressión analysis, it can be appreciated that the independent variables of ESP and LSP do affect the influence in mothers’ purchasing behavior from child to mother, having an R2 = 0.438, and levels of sig. <0.01 for both independent variables as predictors of the dependent variable, for which H3 is supported.

After performing the regressión analyses to test the moderatión with respect to the ESP (Model 2a) and LSP (Model 2b)on influence in purchasing behavior from child to mother, in neither of the two cases the required level of sig. <0.05 in the regressión coefficients is achieved; hence, H4 is not supported.

These results demonstrate that expenditure levels in purchases of products such as toys do not affect the relatiónship of passive social power, be it legitimate or expert,on influence in purchasing child-mother.

Discussión

Notwithstanding that the topic has been well addressed in the past, difficulties in finding specific recent sources about it were encountered. The topic has been left aside because the influence child-mother is assumed as being part of the direct reference group. It is recommended to test the whole model to more enrich the findings regarding the topic in questión.

Having been this research project a pilot to test the research model in our context, it still remains a topic for future research in terms of sample size, locatión and other relevant variables that could affect the final results. To start with, the sample size needs to be increased to have a fair representatión of Lima toy stores’ formal market and validate the results of the pilot test.

Then, applicatión of the model should be expanded to other city areas to answer the questión of do the results hold true for different toy store localizatións? Any significant differences can then be researched. After this, other provinces in the country can be studied to compare results to the capital and amongst themselves to identify similarities and difference. The study could be replicated in other Latin American countries to see ramificatións within this context.

This study focusedon 8-11-year-old children, a variable that can have affected the preliminary results in a specific way that might not be representative of younger and older children. Hence, research could also include the applicatión of this model to a younger group of children, as well as to teenage kids, to better understand the mothers’ perceptión of the relatiónship of their children influence with LSP and ESP types. Also, the applicatión of the other three types of social power can be incorporated to the study. This to identify whichone also applies in our local context and even identify if anyone of them weighs moreon the influence of toy purchases and how they compare to theones already identified.

Being that the test subjects for this research were mothers, it would be interesting to survey by gender to ascertain if this would render any differences, and if so, to what level. Also, variables such as the children age, level of expenditure, marital status and the frequency of visits to toy stores could be included with more detail in future research projects.

Finally, the aspect of cultural differences and cultural contexts may very well arise as a result of expanding this study to other countries and regións, where the differences could be studied from the perspective of cultural differences or even the level of socio-economic development of the country or región: developed countries, emerging countries and underdeveloped countries.

Contributión

The informatión that this study brings can provide a better understanding of consumer behavior for toys, providing insights into motivatións and the purchasing process of toys. This then allows companies to better identify their target markets and develop better marketing programs for their target markets by taking into consideratión the role that children haveon the purchasing decisión process because of their levels of influence, as perceived by the mothers. Specifically, the informatión resulting from this research can help design more effective and efficient marketing communicatión programs to better communicate with their target markets, children and mothers, and specifically take advantage of the child-mother binomial.

For one, toy stores should focus moreon the binomial child-mother and the manner in which influence emerges. Having the legitimate passive social power, more weight on the influence in purchasing means that there exists a possibility that the mother concedes to the child’s purchasing attempt, but this must be worked by the stores, specifically by the salespeople. Talking should be done to the binomial, to the mother and the child, for even thoughone pays, the other is who will be the user, and if the user does not want it, the purchase will not be finalized. In additión, the final user might have a level of expertise regarding the toy and be in the positión to influence the mother’s purchasing behavior if she sees him or her as an expert on the subject.

Regarding part of the aspect store layout, the objective can be to make each toy store a space full of experiences for the children as the majority of mothers enter a toy store for the simple fact that their child will entertain himself/herself in the store, for which the following is proposed: provide spaces where children can play with the toys, allowing them to test toys, and the mother and the child tests and experiments with the toys. This even allows them, mother and children, to spend time together, providing mother with more insight into their children’s likes and preferences.

Conclusións

The passive ESP does not positively correlate to any of the dimensións of the influence in purchasing (mother-child). The passive LSP does not positively correlate to any of the dimensións of the influence in purchasing (mother-child). In conclusión, the results of Flurry and Burns (2005) are not supported in this internatiónal context.

Additiónally, taking as external dependent variable the influence in purchasing (childmother) ofatoy, theresultofcrossingitwiththe four dimensións, this variable correlated principally with the passive social power, ESP and LSP. Thus, we can say that the passive social power has the two independent dimensións significant for the present study.

Specifically, within the construct of passive social power, the dimensión with the best correlatión is the passive LSP. Basing ourselveson the theory (Flurry and Burns, 2005; Swasy, 1979; French and Raven, 1959), it is an innate power that is found in the person that exerts the power because the persononly has in common with the other person a strong link, in this case of child-mother.

References

Aldea, R.-E. and Brandabur, R.E. (2012), "Children in family purchase making a theoretical review", Ovidius University Annals, Series Economic Sciences, Vol. 12, pp. 579-584. [ Links ]

Alonso, R.J. and Grande, E.I. (2013), Comportamiento del consumidor: decisiónes y estrategias de marketing, 7ma. ed., Gráficas Dehon, España. [ Links ]

Andina (2010), "Gestión", Junio, 17, from Gestión: http://gestión.pe/noticia/496628/mercado-juguetesmueve-us-80-millones-anuales-peru (accessed 11 November 2015). [ Links ]

Andina (2013), "Los Andes", April, 29, from Los Andes: www.losandes.com.pe/Naciónal/20130429/ 70931.html (accessed 11 November 2015). [ Links ]

Arzu, S. (2011), "Influence of adolescentson family purchasing behavior: perceptións of adolescents and parents", Social Behavior and Personality, pp. 747-754. [ Links ]

Atkin, C. (1978), "Observatión of parent-child interactión in supermarket decisión-making", Journal of Marketing, Vol. 42 No. 4, pp. 41-45. [ Links ]

Beatty, S.E. and Talpade, S. (1994), "Adolescent influence in family decisión making: a replicatión with extensión", Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 21 No. 2, pp. 332-341. [ Links ]

Cartwright, D. (1959), "A field theoretical conceptión of power", Institute for Social Research, pp. 183-220. [ Links ]

Cartwright, D. (1965), "Influence, leadership, control", in McNally, R. (Ed.), Handbook of Organizatións, Chicago, IL, pp. 1-47. [ Links ]

Cartwright, D. and Zander, A. (1968), Group Dynamics: Research and Theory, 3rd ed., Harper & Row, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Coleman, J. (1973), The Mathematics of Collective Actión, Aldine, Chicago, IL. [ Links ]

Corfman, K. and Lehman, D. (1987), "Models of cooperative group decisión-making and relative influence: an experimental investigatión of family purchase decisións", Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 14 No. 1, pp. 1-13. [ Links ]

Cowan, G. and Avants, S. (1988), "Children’sinfluence strategies: structure, sex differences, and bilateral mother-child influence", Child Development, Vol. 59 No. 5, pp. 1303-1313.

Cowan, G., Drinkard, J. and McGavin, L. (1984), "The effects of target, age, and genderon use of power strategies", Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 47 No. 6, pp. 1391-1398. [ Links ]

El Comercio, D. (2014), "Niños influyen en la compra en el 62% de los hogares limeños", available at: https://elcomercio.pe/economia/peru/ninos-influyen-compra-62-hogares-limenos-181530 (accessed 11 November 2015).

Elias, S. (2008), "Fifty years of influence in the workplace", Journal of Management History, Vol. 14 No. 3, pp. 267-283. [ Links ]

Flurry, L. and Burns, A.C. (2005), "Children’sinfluence in purchase decisións: a social power theory approach", Journal of Business Research, Vol. 58 No. 5, pp. 593-601.

Foxman, E., Tansuhaj, P. and Ekstrom, K. (1989a), "Adolescents’ influence in family purchase decisións: a socializatión perspective", Journal of Business Research, Vol. 18 No. 2, pp. 159-172.

Foxman, E., Tansuhaj, P. and Ekstrom, K. (1989b), "Family members’ perceptións of adolescents’ influence in family decisión making", Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 15 No. 4, pp. 482-491.

French, J. (1956), "A formal theory of social power", Psychological Review, Vol. 63 No. 3, pp. 181-194. [ Links ]

French, J. and Raven, B. (1959), in Cartwright, D.P. and Arbor, A. (Eds), The Bases of Social Power, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan, MI. [ Links ]

Goodrich, K. and Mangleburg, T. (2010), "Adolescent perceptións of parent and peer influenceson teen purchase: an applicatión of social power theory", Journal of Business Research, Vol. 63 No. 12, pp. 1328-1325. [ Links ]

Hair, J.F. Jr, Black, W.C., Babin, B.J. and Anderson, R.E. (2014), Multivariate Data Analysis: Pearson New Internatiónal Editión, 7th ed., Pearson Educatión Ltd, London. [ Links ]

INEI (2015a), "INEI Prensa", from INEI Prensa: www.inei.gob.pe/prensa/noticias/9-millones-752-millimenos-celebran-480-anos-de-fundación-de-la-ciudad-de-lima-8173/ (accessed 17 January 2015). [ Links ]

INEI (2015b), "INEI Prensa", June 6, 2015, from INEI Prensa: www.inei.gob.pe/prensa/noticias/en-elperu-15-millones-de-mujeres-celebran-su-dia-8247/ (accessed 11 November 2015). [ Links ]

INEI (2015c), "INEI Prensa", July 9, 2015, from INEI Prensa: www.inei.gob.pe/prensa/noticias/al-30-dejunio-de-2015-el-peru-tiene-31-millones-151-mil-643-habitantes-8500/ (accessed 30 June 2015). [ Links ]

Ipsos Perú (2015), Perfiles zonales – Lima Metropolitana 2015, Ipsos Marketing, Lima. [ Links ]

Isler, L., Popper, E. and Ward, S. (1987), "Children’s purchase requests and parental responses: results from a diary study", Journal of Advertisement Research, pp. 28-39.

Kim, C., Lee, H. and Hall, K. (1991), "A study of adolescents’ power, influence strategy, and influenceon family purchase decisións", Marketing Theory Applicatións, Vol. 2, pp. 37-45.

Lewin, K. (1951), Field Theory in Social Science, Harper, New York, NY. [ Links ]

McNeal, J. (1988), "Tapping the three kids’ markets", American Demographics, pp. 37-41.

McNeal, J. (1992a), Kids as Customers: A Handbook of Marketing to Children, Lexington Books, New York, NY. [ Links ]

McNeal, J. (1992b), "The little shoppers", American Demographics, pp. 48-53. [ Links ]

McNeal, J. (1999), The Kids Market: Myths and Realities, Paramount Market, New York, NY, p. 272. [ Links ]

Nicholls, A.J. and Cullen, P. (2004), "The child–parent purchase relatiónship: ‘pester power’, human rights and retail ethics", Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, Vol. 11 No. 2, pp. 75-86.

Nunally, J.C. and Bernstein, I.H. (1994), Pyschometric Theory, McGraw Series in Psychology, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Olson, D., Cromwell, R. and Klein, D. (1975), "Beyond family power", in Cromwell, R. and Olson, D. (Eds), Power in Families, Wiley, New York, NY, pp. 235-240. [ Links ]

Podsakoff, P. and Schriesheim, C. (1985), "Field studies of French and Raven’s bases of power: critique reanalysis, and suggestións for future research", Psychological Bulletin, Vol. 97 No. 3, pp. 387-411.

Raven, B. (1993), "The bases of power: origins and recent developments", Journal of Social Issues, Vol. 49 No. 4, pp. 227-251, doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1993.tb01191.x. [ Links ]

Roedder, J. (1999), "Consumer socializatión of children: a retrospective look at twenty-five years of research", Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 26 No. 3, pp. 183-213. [ Links ]

Sellers, P. (1989), "The ABC’s of marketing to kids", Fortune, Vol. 119 No. 10, pp. 114-118.

Sener, A. (2011), "Influences of adolescentson family purchase behaviour: perceptións of adolescents and parents", Social Behavior and Personality: An Internatiónal Journal, Vol. 39 No. 6, pp. 747-754. [ Links ]

Smith, T.E. (1970), "Foundatións of parental influence upon adolescents: an applicatión of social power theory", American Sociological Review, Vol. 35 No. 5, pp. 860-873. [ Links ]

Sprey, J. (1975), "Family power and process: toward a conceptual integratión", in Cromwell, R.E. and Olson, D.H. (Eds), Power in Families, pp. 61-79. [ Links ]

Swasy, J.L. (1979), "Measuring the bases of social power", Advances in Consumer Research, Vol. 6 No. 1, pp. 340-346. [ Links ]

Turccínková, J., Brychtová, J. and Urbánek, J. (2012), "Preferences of men and women in the Czech Republic when shopping for food", Acta Universitatis Agriculturae Et Silviculturae Mendelianae Brunensis, Vol. 60 No. 7, pp. 425-432. [ Links ]

Turner, J., Kelly, J. and McKenna, K. (2006), "Food for thought: parents’ perspectives of child influence", British Food Journal, Vol. 108 No. 3, pp. 181-191.

Ward, S. (1972), "Children’s reactións to commercials", Journal of Advertising Research, Vol. 12, pp. 37-45.

Weber, M. (1962), Basic Concepts in Sociology, Philosophical Library, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Wells, W.D. (1965), "Communicating with children", Journal of Advertising Research, Vol. 5 No. 2, pp. 2-14. [ Links ]

Williams, L. and Burns, A. (2000), "Exploring the dimesiónality of children’s direct influence attemps", Advertisement Consumer Research, pp. 64-71.

Wimalasiri, J. (2000), "A comparison of children’s purchase influence and parental response in Fiji and United States", Journal of Internatiónal Consumer Marketing, Vol. 12 No. 4, pp. 55-73.

Corresponding author

Nestor U. Salcedo can be contacted at: nsalcedo@esan.edu.pe

Received 29 January 2018

Accepted 31 January 2018