Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Science

versão impressa ISSN 2077-1886

Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Science vol.23 no.46 Lima dez. 2018

The impact of monetary policy on Islamic bank financing: bank-level evidence from Malaysia

Muhamed Zulkhibri1

1 Islamic Research and Training Institute, Islamic Deoelopmeni Bank, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

Abstract

Purpose - This paper aims to examine the distributional differences of Islamic bank financing responses to financing rate across bank-specific characteristics in dual banking system The study also aims to provide understanding of how efficiently Islamic banks perform their roles as suppliers of capital for businesses and entrepreneurs.

Design/methodology/approach - The study uses panel regression methodology covering all Islamic banks in Malaysia, The study estimates the benchmark model for Islamic bank financing with respect to bank characteristics and monetary policy.

Findings - The evidence suggests that bank-specific characteristics are important in determining Islamic financing behaviour, The Islamic financing behaviour is consistent with conventionallending behaviour that the Islamic bank financing opera tes depending on the level of bank size, liquidity and capitaL There is no significant difference between Islamic bank financing and conventional bank lending behaviour with respect to changes in monetary policy.

Originality/value - Many problems and challenges relating to Islamic financing instruments, financial markets and regnlations must be addressed and resolved, In practice, it would be a good idea if Islamic banks move away from developing debt-based instruments and concentrate more efforts to develop profit and loss sharing instruments.

Keywords: Malaysia, Islamic banks, Bank financing, Base financing rate

1. Introduction

Islamic bank is a deposit-taking institution with all functions similar to currently known modem banking activities but with Islamic-bearing products only offered by the bank. Islamic bank mobilizes funds based on Mudarabah (profit-sharing) or wakalah (as an agent charging a fixed fee for managing funds) as part of its liabilities, while financing of a profit- and loss-sharing (PLS) basis or through the purchase of goods (on cash) and sale (on credit) or other trading, leasing and manufacturing activities as part of the assets. Except a part of demand deposits, which are treated as interest-free loans from the clients to the bank and are guaranteed to be repaid in full, it plays the role of an investment manager for the owners of deposits akin to universal bank. Underpinning the Islamic banking system is the principie, which is derived from a set of rules stemming for the Shari'ah rules [1].

Unlike the conventional banking principies, the basic principies of Islamic banking can be characterised by the following features (Iqbal, 1997): risk-sharing, in which providers of financial capital and the entrepreneurs should share business and financial risks in return for shares in the profits; money as "potential", that is, it becomes the actual capital only when it joins hands with other resources to undertake a productive activity; prohibition of speculative behaviour that discourages hoarding and prohibits transactions featuring extreme uncertainties, gambling and risks; and Shari'ah-approved activities that only those business activities that do not violate the rules of Shari'ah qualify for investment.

On the other hand, many scholars argue that Islamic banking mimics conventional banking schemes, in particular the operational aspects of the bank. This includes the c1aim that most of Islamic financing has a debt-like character and is not based on the true principies of Shari'ah (Aggarwal and Yousef, 1999; El-Gamal, 2006; Hamoudi, 2007), i.e. there is no substantial difference between mark-up and interest. The main difference between the two is the legal formo El-Gamal (2005) has concluded that Islamic finance is primarily a form of rent-seeking legal arbitrage and seeks to replicate the operations of conventional financia! instruments. Nevertheless, as an altemative finance, sorne researchers have argued that Islamic financial institutions have a huge potential to absorb macro-financial shocks and promote economic growth (Dridi and Hasan, 2010; Mills and Presley, 1999).

In terms of deposit, Islamic banks mainly use the risk-sharing PLS instruments, while in financing, most Islamic banks rely on debt-like instruments such as mark-up financing and a guaranteed profit margin, that are based on deferred obligation contracts. Moreover, conventional interest rate, i.e. the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR) or a domestic equivalent, will always be a benchmark for Islamic banks' mark-up or profit margino As a result, in the case of such debt-like instruments, the pricing of Islamic financing is not a function of real economic activity but is based on a pre-determined interest rate plus a credit risk premium.

The objective of the paper is to investigate the impact of monetary policy on Islamic financing behaviour while taking into consideration bank-specific characteristics. The study aims to provide understanding of how efficiently Islamic banks perform their roles as suppliers of capital for businesses and entrepreneurs. Since the rate of retum on retail PLS accounts closely follow interest rates offered by conventional banks in the case of Malaysia (Chong and Liu, 2009; Cervik and Charap, 2011), little is known about Islamic financing behaviour, which is operated alongside with the conventional banks.

This paper is set out as follows: Section 2 overviews of Malaysian Islamic finance industry. Section 3 provides the theoretical view of Islamic financing and profit rateo Section 4 presents the data and methodology. Section 5 provides the empirical results and the paper is rounded off by Section 6 with concluding remarks.

2. Overview of Malaysian Islamic financial industry

Malaysia's Islamic finance industry has been in existence for over 30 years. The enactment of the Islamic Banking Act 1983 enabled the country's first Islamic bank (Bank Islam Malaysia Berhad) to be established. Malaysia's overall strategy in the development of Islamic banking can be summarized under four pillars:

-

full-fledged Islamic banking system operating on a parallel basis with a fullfledged conventional system (dual banking system);

-

step-by-step approach, in the context of an overalllong term strategy;

-

comprehensive set of Islamic banking legislation and a common Shari'ah Supervising Council for all Islamic banking institutions; and

-

practical and open-minded approach in developing Islamic financial interests[2].

Three basic elements have been adopted in the implementation of Islamic banking in Malaysia to create a viable and dynamic Islamic banking system:

-

a large number of instruments and range of different types of financial instruments must be available to meet the different needs of different investors and borrowers;

-

a large number of institutions with adequate number of different types of institutions participating in the Islamic banking system to provides depth to the Islamic banking system; and

-

an Islamic interbank market to support an efficient and effective system linking the system to the institutions and the instruments.

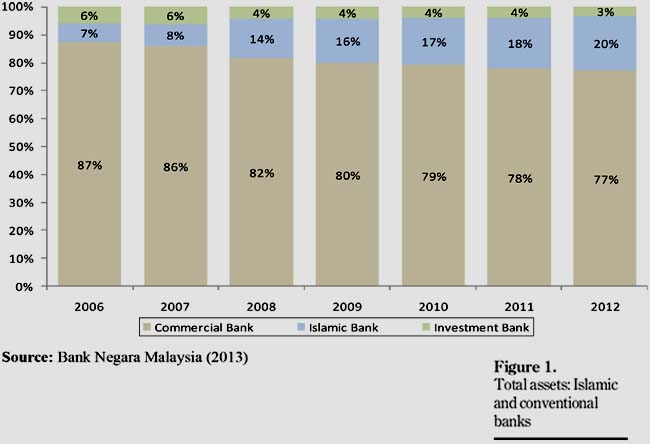

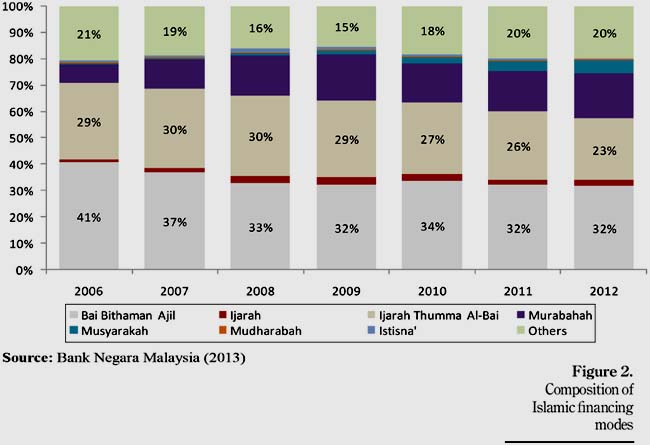

Figure 1 shows the share of Islamic assets in overall banking system is growing significantly, from around 7 per cent in 2006 to 20 per cent in 2012. As at end-2012, the country's Islamic banking system has accumulated a total of RM 119bn in assets or about 20 per cent of the total assets of the banking sector, which is RM 0.6tn[3]. To date, Malaysia has 16 Islamic banks, which comprise nine local Islamic banks and seven foreign Islamic banks [4]. Figure 2 shows the composition of Islamic financing modes. It shows that the Bai Bithaman Ajil and Ijarah Thumma Al Bai dominate the composition with 32 per cent and 23 per cent, respectively, over the period 2006-2012[5]. This dominance trend of using mark-up and debt-like instrument in the Islamic financing practices supports sorne of the arguments that Islamic banking is akin to conventional banking in practical term.

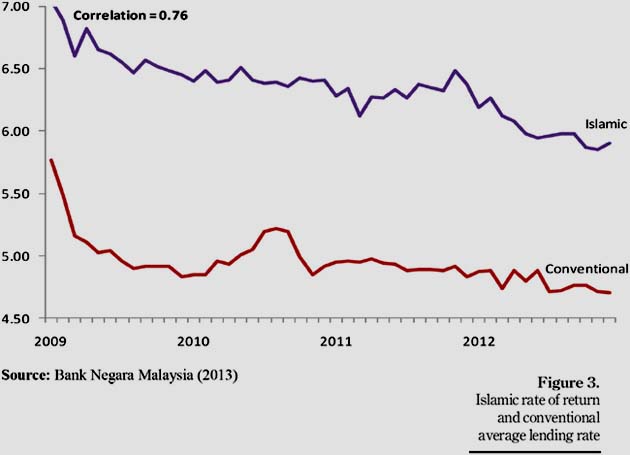

Figure 3 illustrates a high level of correlation between Islamic base financing rate (BFR) on retail financing and conventional lending rates on loans in Malaysia. Between 2009 and 2012, the correlation of base lending rate of conventional bank and the Islamic base financing rate is about 76 per cent. Accordingly, even though conventional and Shariah compliant banks Islamic bank operate in different banking environment, it is surprising that the Islamic base financing rate closely tracks interest rates offered by conventional banks in Malaysia.

3. Related literature

Islamic banking is different from conventional banking from a theoretical perspective because interest (riba) is prohibited in Islam (rate of return on deposits cannot be fixed by the bank and interest cannot be charged on loans). A unique feature of Islamic banking is the PLS paradigm, which is largely based on the Mudarabah (profit-sharing) and musharakah (equity participation) concepts of Islamic contracting. This means that the ideal and most "Islamic" form of each concept should be accepted as the valid. The concepts of Islamic finance on using the rate of returns as replacement for interest can be divided into two strands of arguments. The idealist literature that attempts to look at the key concepts of Islamic finance such as PLS, money, interest and profit from an ideal perspective. Much of the literature on Islamic banking and finance in the 1960s and the theoretical studies on Islamic banking fall under this category.

Another line of argument is based on Maslahah-oriented literature would be at the extreme end of the continuum. According to this view, riba should not be interpreted in a simplistic fashion as modem bank interest. Any interest-based bank could theoretically be an Islamic bank provided that the Islamic ideals of justice, equity, faimess, non-exploitation were its guiding principles; the humane terms of providing finance to those "needing" them were practiced; and one ways of helping the economically disadvantaged classes of the society to raise their standard of living. Nonetheless, it can be seen from this that there has been a gradual shift from the idealist position to a more pragmatic, mark-up based and less risky version.

In the conventional literature, the interest rate has long been recognized not only by classical and neo-classical economists, but also by contemporary economist as one of the factors that determine the level of savings in the economy and that interest rate has a positive relationship with savings. However, Haron (2001) find a similar positive relationship behaviour of profit rate declared by Islamic banks. In other words, Islamic bank customers are guided by the profit maximization theory, as there is no pre-determined rate of retum involved in Islamic banking system. Because depositors at Islamic banks possess similar attitudes to those at the conventional banks, the interest rate will continue to have an influence on the operations of Islamic banks.

In line with other studies, funding activities of Islamic banks are mainly carried out through the participatory PLS model. It is well established in the literature that Islamic banks follow their conventional counterparts in creating assets through non-PLS, debt-like instruments with a predetermined, fixed rate of return (Beck et al., 2013). The study argues that there are "few significant differences in business orientation, efficiency, asset quality or stability" between conventional and retail Islamic banks. As a result, given the implicit link to interest rates on the asset side of the balance sheet, PLS rate of retums follow conventional bank deposit rates.

Recent literature on Islamic finance also try to establish the difference between Islamic rate of returns and conventional banks interest rate based on empirical assessments (Chong and Liu, 2009; Kasri and Kassim, 2009; Cervik and Charap, 2011; Ito, 2013; Ergec and Arslan, 2013; Sarac and Zeren, 2015). Cervik and Charap (2011) compare the empirical behaviour of conventional bank deposit rates and the rate of returns on retail Islamic PLS investment accounts in Malaysia and Turkey. The findings show that conventional bank deposit rates and PLS rate of retums exhibit long-run cointegration and that conventional bank deposit rates Granger cause retums on PLS accounts. Moreover, the time-varying volatility of conventional bank deposit rates and PLS returns are correlated and are statistically significant.

Similar correlations have been observed in other studies. In the case of Malaysia, Chong and Liu (2009) find that retail Islamic deposit rates mimic the behaviour of conventional interest rates. The study shows that only a small portion of Islamic bank financing is strictly PLS-based and that Islamic deposits are not interest-free but are very much pegged to conventional deposits. The findings also suggest that the Islamic resurgence worldwide drives the rapid growth in Islamic banking rather than the advantages of the PLS paradigm, implying that similar regulations of conventional bank should be applied for the Islamic bank. This is supported by Ito (2013), who suggests that conventional interest rates and Islamic rates of retum co-move in the case of Malaysian deposit market.

In terms of the behaviour of Islamic bank deposit, Kasri and Kassim (2009) examine the relationship between investment deposit and rate retum inc1uding interest rate for Islamic banks in Indonesia over the period of 2000 to 2007. Using vector autoregressive model (VAR) model, the study reveals that the Mudarabah investment deposit in the Islamic banks are cointegrated with return of the Islamic deposit, interest rate of the conventional banks' deposit, number of Islamic banks' branches and national income in the long-run. The finding also suggests that rate of return and interest rate move in tandem, indicating that Islamic banks in Indonesia are exposed to benchmark risk and rate of return risk.

Ergec and Arslan (2013) investigate the impact of interest rate shock on deposits and loans held by conventional and Islamic banks in Turkey, while Sarac and Zeren (2015) investigate the long-term relationship between conventional banks term-deposit rates and participation banks in Turkey. Both findings point to similar conc1usion that that movements in the overnight interest rate have asymmetric effects on Islamic and conventional banks in Turkey and significantly cointegrated with those of conventional banks.

A more recent work by Akhatova et al. (2016) examines the response of Islamic banks to monetary policy shocks is evaluated by using the structural vector autoregression (SVAR) specification. The study shows that Islamic banks' response toward interest rate hikes is immediate as compared to its conventional counterparts. This conc1usion is supported by Aysan et al. (2017) that Islamic bank depositors' sensitivity to policy rate changes is substantially larger than that of conventional bank depositors. On the other hand, Mushtaq (2017), using the panel ARDL approach on 23 Muslim countries, finds that there is no significant relationship between Islamic banking deposit and interest rate, leading to the fact that Islamic banks are resilient towards shocks.

In practice, the main explanation of the similarity between Islamic bank profit rate and conventional bank can be attributed to the differences in perceptions of riskiness (theoretically and practically) at the institutional and systemic level, particularly on the asset side. In addition, Islamic banks lose on the grounds of liquidity, assets and liabilities concentrations and operational efficiency, whereas what they tend to win in the field of profitability. Nevertheless, Islamic banking could be a further guarantee, however still marginal, against systemic risks in certain emerging financial markets.

4. Data and estimation methodology

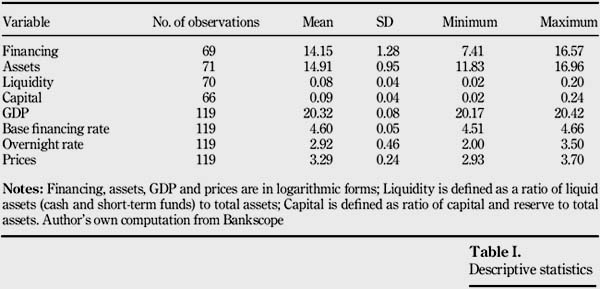

The study uses a panel of annual bank-Ievel data of all Islamic banks operating in the Malaysia covering the period 2006-2012. The financial statements of Islamic banks operating in Malaysia Islamic banking sectors are collected from the Bankscope database of Bureau van Dijk's company. The macroeconomic variables: consumer price index, real gross domestic product, Islamic base financing rate (BFR) and policy rate are taken from various issues of Quarterly Statistical Bulletin published by Central Bank of Malaysia. Table 1 reports the basic descriptive statistics for the sample.

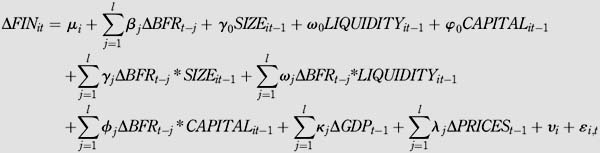

Using a panel information of 17 individual banks, we initially estimate the benchmark model for Islamic bank financing with respect to bank characteristics and monetary policy. This has usually been done by introducing interaction terms between Islamic base financing rate and bank discriminatory variables. Beside these variables, we control for economic activities and consumer prices, which allow us to control for demand-side effects on Islamic bank financing. By combining time series of cross-section observation, panel data give more informative data, more variability, less co-linearity among the variables, more degree of freedom and more efficiency (Cujarati and Sangeetha, 2007). Panel-data estimation method of both pooledregression and fixed-effect model is preferred. Fixed-effects specification is mainly used to account for time-invariant unobservable heterogeneity that is potentially correlated with the dependent variable. To test for estimation robustness of the models, we use random-effect estimations and use all diagnostic tests to validate the models. Our baseline model specification is as follows:

where is Δ the first-difference operator, FIN is the Islamic banks financing, GDP is the logarithm of real GDP, PRICES is the logarithm of consumer price index and BFR[6] is the Islamic financing rate, and SIZE, LIQUIDITY and CAPITAL are the bank size, liquidity and capitalisation, respectively. The subscript i denotes banks where i = 1, ..., N; t denotes time where t = 2006-2012; νt denotes individual bank effects; and εi,t denotes error-term.

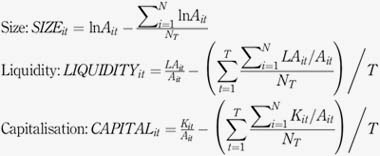

The choice of bank-specific characteristics is based on the theor~tical assumptions that a certain type of bank is expected to be more responsive to financing shocks since it operates in a dual banking system and these characteristics are widely used in the empirical literature, Following Gambacorta (2005) and Zulkhibri (2013), the three measures for bank characteristics size (SIZE), liquidity (LIQUIDITY) and capitalisation (CAPITAL) are defined as follows:

Bank size (SIZE) is measured by the logarithm of total assets (A). Relatively, banks with a smaller size may face higher constraints to raise external funds and thus be forced to reduce their lending (Kashyap and Stein, 1995, 2000)0 Liquidity (LIQUIDITY) is measured by the ratio of liquid assets (cash and short-term funds) to total assets (LA). More liquid banks can draw down on their liquid assets to shield their financing portfolios and less likely to cut back on financing in the face of rising cost or rate of return, Capitalization (CAPITAL) is measured by the ratio of capital and reserve to total assets (K). Because raising bank capital is costly, the bank tends to adjust the lending behaviour to meet the required level of capital. In the face of rising rate of return, banks' cost of financing rises, while the remuneration of bank assets remains the same, Hence, financing of highly leveraged bank is expected to be more responsive to changes in the rate of return than financing of well-capitalised banks (Kishan and Opelia, 2006).

All three criteria are normalised with respect to their average (NT) acrass all the banks in the respective sample to get indicators that sum to zero over all observations, For equation (1), the average of the interaction term (ΔBFR*SIZE, ΔBFR*LIQUIDITY and ΔBFR*CAPITAL) is therefore zero, and the parameters are directly interpretable as the overall Islamic rate of return effect on Islamic bank financing. To remove the upward trend in the case of size (refiecting that size is measured in nominal terms) or the overall mean in the case of liquidity and capitalisation, the bank characteristic variables are defined as deviations from their crass-sectional means at each period.

The assumption is that small, less liquid and poorly capitalised banks react more strongly to changes in base financing rateo This would correspond to a significant positive coefficient for the interaction terms, ΔBFR*SIZE, ΔBFR*LIQUIDITY and ΔBFR*CAPITAL, meaning that banks with these characteristics reduce their financing growth rate more strongly in response to a restrictive shock of base financing rate than larger, more liquid and well-capitalised banks.

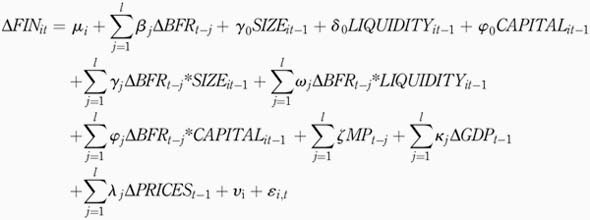

Because the Islamic bank operates in the dual banking system, conventional interest rate may influence the Islamic bank financing behaviour, Equation (1) may represent the overall effect of Islamic bank financing without the monetary policy, Huang (2003) argues that under the conventional system, changes in interest rates have a larger effect on bank loans supplies because banks ability to insulate their financing supplies from changes in monetary policy will be restricted during periods of tight monetary conditions. We try to test this hypothesis for Islamic financing behaviour by inc1uding monetary policy rate where MP is monetary policy shock praxy by overnight policy rate in equation (3) and estima te the following model:

5. Empirícal results

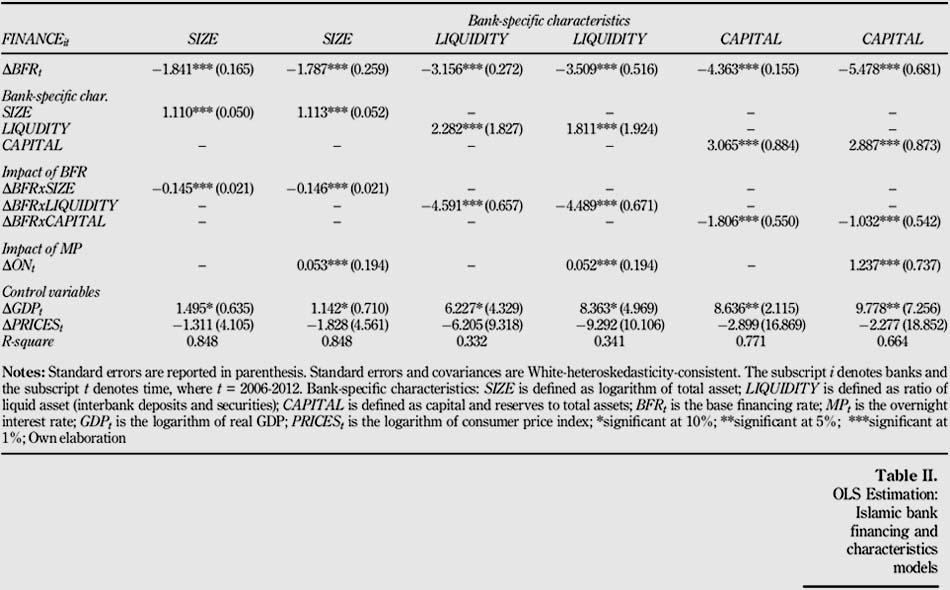

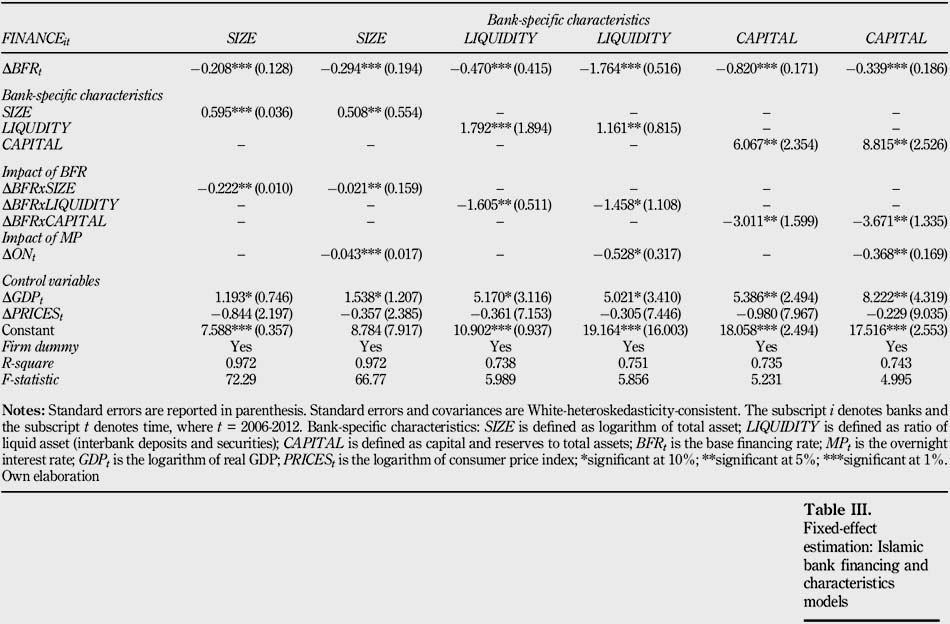

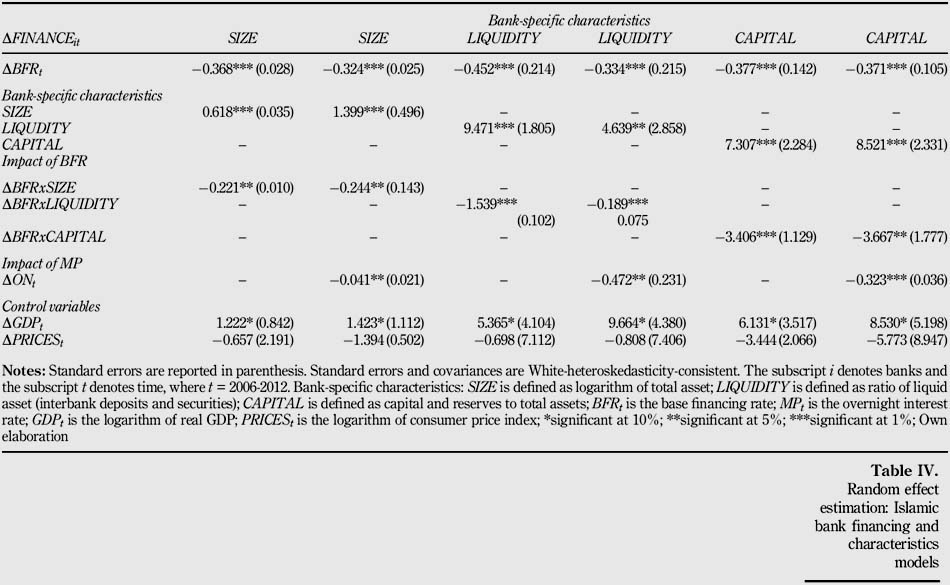

Table II reports the results for our benchmark model of Islamic bank financing, while Tables III-IV report the results from fixed-effect and random-effect. The direct impact of changes in the base financing rate on bank financing is negative and significant. The coefficients for base financing rate ranges from 1.78 to 5.47, which means that an increase of base financing rate by one percentage point leads to a decrease in the bank financing in the range between 1.7 per cent to 5.5 per cent. The result of our benchmark models in line with the basic theoretical prediction is similar to the lending channel of the conventional bank (Ehrmann et al., 2003). Because the Islamic rate of return implicitly tracks interest rates offered by conventional banks (Chong and Liu, 2009), the results also explain that the reduction in Islamic bank deposits may not be completely substituted by other form of financing, to continue to meet financing demand, thus lead to a reduction in Islamic bank financing. The results for fixed-effect and random-effect provide similar observation albeit with a lower impact of base financing rate on bank financing between -0.21 and -1.76. The estimated regression equations for all models explain the behaviour of financing in the range of 30 per cent to 97 per cent. AH diagnostic tests confirm the good fit of the models.

The results from Tables II to IV also show the important of bank-specific characteristics with respect to the bank lending behaviour. The variable of SIZE is positive and highly significant for all models. In the fixed-effect and random-effect model, the SIZE is positive and significant ranging from 0.51 to 1.39. Larger banks might be more efficient due to scale economies, while the theoretical and empirical literature on the relationship between size and stability is ambiguous (Beck et al., 2013). This suggests that size is an important factor characterising the banks financing reaction with large banks are expected to minimizing costo The finding is also consistent with Fadzlan and Zulkhibri (2009), suggesting that larger financial institutions in Malaysia atta in a higher level of technical efficiency in their operations and exhibit an inverted U-shape behaviour.

In the case of the liquidity, the results show that the coefficient of LIQUIDITY is positively associated and highly significant with bank financing in between 1.16 and 9.47. Only banks that have a larger share of liquid assets or that are bigger can shield their lending relationships. This evidence points to the fact that Islamic banks can protect their financing portfolios by drawing down on their liquid assets and are therefore less likely to cut on financing, whereas the latter have better access to external finance owing to their size to retain their preferred liquidity ratio. This finding also implies that, in periods of rising base financing rate, a borrower from a less liquid bank, on average, tends to suffer from a sharp dec1ine in financing than does a customer of a more liquid bank. The result is in line with the findings by Brooks (2007) that finds liquidity as the main determinant explaining credit supply in Turkey.

Looking at the coefficient of capitalisation, CAPITAL, it appears that bank financing is positively associated with bank capitalization or the bank capital structure. The results suggest that market participants may perceive highly capitalized banks as being les s risky (Kishan and Opiela, 2000). Consequently, it should be more expensive for poorly capitalized banks to finance externally. Those poorly capitalised banks try to avoid the cost of falling below the regulatory minimum capital requirements or the increased risk of violating the capital requirement by holding capital buffers and asset buffers (short-term risk-weighted assets than customer financing) that can be liquidated if the bank runs into problems with the capital requirement. The more short-term risk-weighted assets (other than customer loans) the bank holds on its balance sheet (i.e. the higher the bank's asset buffer), the lower the risk of violating the capital requirements will be. The short-term risk-weighted assets will soon be liquid, thereby reducing the capital requirement in the near future. The higher the bank's capital buffer, the lower the risk of violating the capital requirement will be.

The macroeconomic variables inc1uded in the bank financing models to control for the demand-side effect, and only the real GDP growth variable is significant in the equation, where it has a positive coefficient. The response of credit to economic activity is consistent with the expectation. The facts that the coefficient of real GDP is significant may imply that the economic activities are taken into account in financing decision in an important way. On the other hand, the price variable is negatively related to Islamic bank financing but insignificant. The rise in inflation may be associated with the variability of the infiation rate and generate uncertainty about the future return on investments. This in turn discourages firms from undertaking investments and consequently reducing their financing demand. However, the price variable is insignificant for all regressions results.

Owing to the potential interrelations between Islamic bank financing and conventional interest rate, we run all bank-financing models with overnight policy rate (ON). The coefficients in all regressions are negatively related to bank financing and vary within the reasonable magnitudes (0.05 to 0.52), but broadly lower than the base financing rateo The results of these regressions suggest that the reaction of banks to changes in interest rates remains the same as the change base financing rate and is robust to a different type of econometric specifications. This finding broadly supports the findings that there is no significant different between bank financing behaviour with respect to interest rates (Chong and Liu, 2009; Cervik and Charap, 2011; Ergec and Arslan, 2013; Aysan et al., 2017). Furthermore, Kasri and Kassim (2009) confirm that conventional interest rate is one of the determinants for saving deposits in Indonesia. This evidence explains why the bulk of Islamic bank financing is based either on the mark-up principIe and is very debt-like in nature (i.e. Murabahah and Ijarah) rather than using the principIe of PLS. Despite Islamic bank operation is different from conventional bank, it seems to face asymmetric information, severe adverse selection and moral hazard problems similar to their counterpart in their attempts to provide funds to entrepreneurs. However, the use of debt-like instruments is a rational response on the part of Islamic banks to informational asymmetries in the environments in which they operate.

We have interacted the base financing rate variable with bank size (ΔBFR*SIZE), liquidity (ΔBFR*LIQUIDITY) and capitalisation (ΔBFR*CAPITAL) to further analyse the economic arguments that there is a unique role for Islamic banks in the dual banking system and the importance of heterogeneity among Islamic banks. Table II to Table IV report the results of the base financing rate with respect to bank-specific characteristics for Islamic financing using fixed-effect and random-effect model. The estimates of bank-specific characteristics coefficients provide interesting results. The estímate coefficients of ΔBFR x LIQUIDITY, ΔBFR x CAPITAL and ΔBFR x SIZE consistently show a positive sign and are highly significant at the conventional level. These suggest that bank lending and their ability to obtain other sources of funding are banks are affected indirectly via bank-specific characteristics.

In summary, we find strong evidence of the asymmetric adjustment of bank financing via banks-specific characteristics which have been found in others literature for Islamic bank financing (Chong and Liu, 2009; Kasri and Kassim, 2009; Cervik and Charap, 2011; Ito, 2013; Ergec and Arslan, 2013; Sarac and Zeren, 2015) and conventional bank lending channels in line with the arguments of Kashyap and Stein (1995, 2000) and Kishan and Opiela (2000). Moreover, banks react differently to base financing rate depending on their own specific characteristics, particularly a bank with higher capitalization is expected to increase financing more than bank with greater size and liquidity. Furthermore, as the Islamic bank is operating in a dual banking system, the asymmetric information problems faced by Islamic banks is expected to affect the ability to protect their financing lines from policy-induced reduction in deposits and resulted in Islamic bank financing behaviour.

6. Conclusion

A significant number of empirical studies have explored the bank lending behaviour for conventional banks for the past decades, while studies on Islamic bank financing behaviour remain scarce due to lack of bank-level data. Under the dual banking system, to the extent that financial constraints vary with banks' ability to access other sources of financing implies that Islamic bank financing responses to bank financing rate and conventional interest rate contingent on observable bank-specific characteristics. Understanding this mechanism is crucially important, where Islamic banks have increasingly played a dominant role in Malaysia financial system.

This paper analyses the importance of bank-specific characteristics with respect to Islamic bank financing in Malaysia. The results obtained from pooled panel estimation, allow us to make several significant conc1usions on the Islamic bank financing behaviour in Malaysia within a dual banking system. The evidence gathered in this study suggests that the bank-specific characteristics are important for Islamic banking financing behaviour. The Islamic banks financing behaviour is consistent with behaviour of conventional banks that the bank lending operates via banks with the level of size, liquidity and capital (Golodniuk, 2006). The results of these regressions also suggest that the reaction of Islamic banks financing to changes in interest rates is the same as the conventional banks and are robust to different types of econometric specifications.

Many problems and challenges relating to Islamic instruments, financial markets and regulations must be addressed and resolved. A complete Islamic financial system with its identifiable instruments and markets is still relatively at an early stage of evolution. The functioning of Islamic banks should rapidly differentiate itself from conventional banking. Owing to the existence of moral hazard and adverse selection in the industry, an Islamic bank is not able to provide a full-fledge alternative finance to conventional finance. Moreover, an Islamic bank also does not develop itself in the path that was envisioned by the Islamic scholars (Saeed, 1996). One of the drawbacks is the low level of participation in PLS arrangements, which is seemed to contradictive with the essential concept of Islamic banking. In practice, it would be a good idea if Islamic banks stopped replicating the conventional banking models that mainly concentrated on the debt-based instruments and mark-up models but moved over to the PLS model.

References

Aggarwal, R. and Yousef, T. (1999), "Islamic banks and investment financing", Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking, Vol. 32 No. 1, pp. 93-120. [ Links ]

Akhatova, M., Zainal, M.P. and Ibrahim, M.H. (2016), "Banking models and monetary transmission mechanisms in Malaysia: are Islamic banks different?", Eeonomie Papers: A Journal of Applied Economies and Poliey, Vol. 35 No. 2, pp. 169-183.

Aysan, A.F., Disli, M. and Ozturk, H. (2017), "Bank lending channel in a dual banking system: why are Islamic banks so responsive?", The World Economies, in press, pp. 1-25. [ Links ]

Beck, T., Demirguc-Kunt, A. and Merrouche, O. (2013), "Islamic vs conventional banking: business model, efficiency and stability" Journal Banking and Finance, Vol. 37 No. 2, pp. 433-447. [ Links ]

Brooks, P.K. (2007), "Does the bank lending channel of monetary transmission work in Turkey? ", IMF Working Paper 07/272, International Monetary Fund Washington, DC. [ Links ]

Cervik, S. and Charap, ]. (2011), "The behavior of conventional and Islamic bank deposit returns in Malaysia and Turkey", IMF Working Paper, No. WP/11/156, Intemational Monetary Fund, Washington, DC. [ Links ]

Chong, B. and Liu, M.H. (2009), "Islamic banking: interest-free or interest-based?", Pacific-Hasin Finance Journal, Vol. 17 No. 1, pp. 124-144. [ Links ]

Dridi, J. and Hasan, M. (2010), "Have Islamic banks been impacted differently than conventional banks during the recent global crisis?", IMF Working Paper, No. WP/10/201, Intemational Monetary Fund, Washington, DC. [ Links ]

Ehrmann, M. Gambacorta, L. Martinez-Pages, J. Sevestre, P. and Worms, A. (2003), "Financial systems and the role of bank in monetary transmission in the euro area", In I. Angeloni, A. [ Links ]

El-Gamal, M.A. (2006), Islamic Finance: Laui, Economics and Practice, Cambridge, New York, NY. [ Links ]

El-Gamal, M.A. (2005), "Mutuality as an antidote to rent-seeking sharia-arbitrage in Islamic finance", www.ruf.rice.edu/~elgamal/ [ Links ]

Ergec, E.H. and Arslan, B.G. (2013), "Impact of interest rates on Islamic and conventional banks: the case of Turkcy", Applied Economics, Vol. 45 No. 17, pp. 2381-2388.

Fadzlan, S. and Zulkhibri, M. (2009), "Post-crisis productivity change in non-bank financial institutions: efficiency increase or technological progress?", Journal of Transnational Management, Vol. 14 No. 2, pp. 124-154. [ Links ]

Garnbacorta, L. (2005), "Inside the bank lending channel'', European Economic Review, Vol. 49 No. 7, pp. 1737-1759. [ Links ]

Golodniuk, I. (2006), "Evidence on the bank-lending channel in Ukraine", Research in International Business and Finance, Vol. 20 No. 2, pp. 180-199. [ Links ]

Gujarati, D.N. and Sangeetha, S. (2007), Basic Econometric, 4th ed., McGraw-Hill Education Books, India. [ Links ]

Hamoudi, H.A. (2007), "Jurisprudential schizophrenia: on form and function in Islamic finance", Chicago Journal of International Law, Vol. 7 No. 2, pp. 605-622. [ Links ]

Haron, S. (2001), "Islamic banking and finance", Leading Issues in Islamic Banking and Finance, Vol. 20 No. 1, pp. 17-32. [ Links ]

Huang, Z. (2003), "Evidence of bank lending channel in the UK", Journal of Banking and Finance, Vol. 27 No. 3, pp. 491-510. [ Links ]

Iqbal, Z. (1997), "Islamic financial systcms'', Finance and Deuelopment, June 1997, IMF, Washington, DC.

Ito, T. (2013), "Islamic rates of return and conventional interest rates in the Malaysian deposit market", International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management, Vol. 6 No. 4, pp. 290-303. [ Links ]

Kashyap, A. and Stein, J. (2000), "What do a million observations say about the transmission mechanism of monetary policy", American Economic Review, Vol. 90 No. 3, pp. 407-428. [ Links ]

Kashyap, A. and J. Stein, J. (1995), The impact of monetary policy on bank balance sheets. Camegie Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy, pp. 51-195. [ Links ]

Kasri, RA. and Kassim, S. (2009), "Empirical determinants of saving of the Islamic banks in Indonesia", Journal of King Abdulaziz University-Islamic Economics, Vol. 22 No. 2, pp. 181-201. [ Links ]

Kishan, P. and Opelia, T. (2006), "Bank Capital and loan asymmetry in the transmission of monetary policy" Journal of Banking and Finance, Vol. 30 No. 1, pp. 259-285. [ Links ]

Kishan, P. and Opiela, T. (2000), "Bank size, bank Capital, and the bank lending channel", Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, Vol. 32 No. 1, pp. 121-141. [ Links ]

Mills, P. and Presley, J. (1999), Islamic Finance: Theory and Practice, Macmillan, London, United Kingdom. [ Links ]

Mushtaq, S. (2017), "Effect of interest rate on bank deposits: evidences from Islamic and non-Islamic economics", Future Business Journal, Vol. 3 No. 1, pp. 1-8. [ Links ]

Saeed, A. (1996), Islamic Banking and Interest: A Study of the Prohibition of Riba' and Its Coniemporary Interpretation, EJ Brill, Leiden. [ Links ]

Sarac, M. and Zeren, F. (2015), "The dependency of Islamic bank rates on conventional bank interest rates: further evidence from Turkey", Applied Economics, Vol. 47 No. 7, pp. 669-679. [ Links ]

Zulkhibri, M. (2013), "Bank-characteristics, lending channel and monetary policy in emerging markets: bank-level evidence from Malaysia", Applied Financial Economics, Vol. 23 No. 5, pp. 347-362. [ Links ]

Corresponding author

Muhamed Zulkhibri can be contacted at: khibri1974@yahoo.com

Received 21 January 2018

Revised 25 March 2018

Accepted 4 May 2018

Notes

1. Shari'ah (Islamic law) as defined and interpreted through the Quran (central religious text of Islam, which Muslims believe to be a revelation from Cod), Sunnah (words and actions of Muhamad, the Prophet of Islam) and from elaborative efforts of Shari'ah Scholars.

2. Yakcop, N.M (2003) "From Moneylenders to Bankers: Evolution of Islamic Banking in Relation to Judeo - Christian and Oriental Banking Traditions" Intemational Islamic Banking Conference, Prato Italy, 9-10 September 2003.

3. Based on the exchange rate as at January 2013.

4. Sorne of them are Affin Islamic Bank Berhad, Alliance Islamic Bank Berhad, Bank Muamalat Malaysia Berhad, Kuwait Finance House (Malaysia) Berhad, OCBC Al-Amin Bank Berhad, Public Islamic Bank Berhad, Standard Chartered Saadiq Berhad and others.

5. Bai Bithaman Ajil is deferred payrnent sale; Ijarah Thumma Al-Bai is hire purchase; Musharakah is equity financing; Ijarah is leasing; Istisna' is contract manufacturing; Murabahah is cost-plus; Mudarabah is profit sharing.

6. Base financing rate (BFR) is a minimum profit/interest rate ca1culated by financial institutions based on a formula that takes into account the institution's cost of funds and other administrative costs. Computation of BFR is as follows: (intervention rate x 0.8) + 2.25/(1 SRR). The additional factor of 0.8 % in commercial banks' computation is because the commercial banks give current account facility, which is interest-free, while finance companies do not offer current account facility. The administrative margins of 2.25% is allowed for financial institutions.