Introduction

Higher inflation has been considered a growth retarding factor and a means of reducing the welfare standard of common masses. Therefore, maintaining a stable price level featured by a low inflation rate has remained a priority objective of macroeconomic management of various economies including India. Among the many factors fuelling the inflationary tendencies in an economy like monetary shocks, structural shocks, demand shocks, external shocks, and demographic changes, the issue of inflation has also been found related to fiscal policy decisions of the government. The fiscal theory of price level (Leeper, 1991; Sims, 1994 and Woodford, 2001) and the seminal work of Sargent and Wallace (1981) developed the theoretical contours for the establishment of interaction between inflationary pressures in an economy and the government budgetary imbalances. The former talks about the complementarity between monetary and fiscal policies for the price level determination; and on policy plane, the theory suggests the sustainability of government finances to ensure the stable price level. The latter highlights the role of the relative dominance of monetary/fiscal authorities in the determination of the price level. In a monetary dominance regime, fiscal authorities abide by the decisions of independently determining monetary policy and are constrained to follow a fiscal discipline strategy to avoid the inflationary pressures in the economy. On the contrary, in a fiscal dominance regime, the fiscal authorities determine the level of current and future fiscal imbalances and thereby constrain the monetary authority for the demand of government bonds. This leads to excess money creation through debt monetization and hence inflationary tendencies emerge (Sargent and Wallace, 1981). The deficit could be financed either through the imposition of higher taxes or domestic or external borrowings. However, developing countries quite often finance their deficit through debt monetization due to the high costs associated with higher tax rates, political instability, and market borrowings. As a result, the fiscal view of inflation is more often reported in the developing countries than in developed countries which are seen to have an efficient tax collection system and considerable access to external borrowings (Catao and Terrones, 2005).

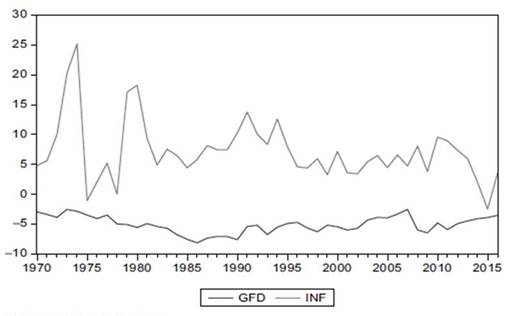

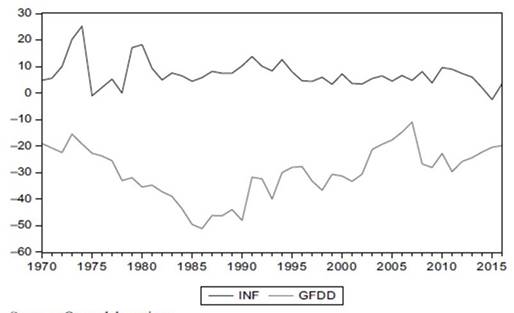

The present paper aims at examining the impact of fiscal deficit on inflation in the case of the Indian economy. Though several studies have been conducted in the Indian context, the deficit-inflation nexus has not been evaluated exhaustively and the evidence reported by earlier studies remained inconclusive. India is chosen as a candidate for analysis due to its vibrant inflation dynamics and its observed downward inflexibility of fiscal deficit. Deficit financing has always been considered a viable instrument to avoid any recessionary tendencies in the economy. Recognizing the adverse impacts of the excess deficit, the government followed the fiscal consolidation program through the FRBM Act (2003-04) and finalized the pro-growth targets for fiscal imbalances. However, the recent fiscal response to the 2008 global crisis, following the suspension of fiscal targets, not only enabled India to avoid the crisis at home but also to continue along its growth trajectory as well. The move, however, represented a deviation from the fiscal discipline path. Even though the efforts have been made to curtail the deficit figures appreciably, the economy is still plagued with a persistent deficit of 3.52% of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2016-17(3). In light of swelling deficit figures and vibrant inflationary phenomenon, as observed from the Figures 1 and 2 in the economy, it would, therefore, be important to examine the possible interaction between these two variables.

Though the inflationary pressures in India have been theoretically ascribed to both domestic and foreign factors and to both supply and demand shocks, however, the empirical evidence reported remains inadequate (Mohanty and John, 2015). The possible reason for such an inadequacy could be the changes in determinants of inflation over the period of time (Mohanty and John, 2015). Given the backdrop, we attempted to analyse the inflationary phenomenon from the viewpoint of fiscal deficit to sort out the likely role of the latter in explaining the overall inflation. Work reported is motivated by lack of adequate literature so far as India is concerned and mixed evidence reported in the general literature on the deficit-inflation nexus. A broader analytical framework has been adopted to include all the potential determinants of inflation in addition to the fiscal deficit.

Data for the period 1970-2016 has been examined to provide an evaluation of the Indian inflationary problem with some recent evidence. The paper hopes to contribute to the existing literature in the following ways. First, taking note of the dynamic nature of the relationship between these two variables, we examined the deficit inflation nexus in a dynamic and asymmetric framework. The novelty of the study is ensured by the very nature of it is the first study in the case of India to identify the fiscal inflation in an asymmetric configuration. We applied a Non-linear Autoregressive Distributed lag model (NARDL) model, given by Shin et al. (2014) to examine the existence, if any, of cointegrating relationship in an asymmetric paradigm. Second, the nature of causality between fiscal deficit and inflation is examined in both time domain and frequency domain frameworks to portray precisely the casual interactions between these two variables in both the short-run and long run.

The studies so far conducted, have primarily based their analysis within a linear or symmetrical framework and have ignored the possibility of any asymmetric nature of the association between the two variables. The severe repercussions of this practice of assuming a symmetric association may lead to incorrect policy actions as may be needed for overall macroeconomic stability. The choice of an emerging economy, India, for the asymmetric investigation of deficit-inflation nexus is motivated by the prevalence of a large section of liquidity constrained population together with persistent inequalities (Mazumdar et al., 2017; Bhat and Sharma, 2018). The lack of purchasing power, liquidity tightening, and a distorted credit allocation system as prevalent in India together with the operation of consumption/investment downward inflexibility makes it likely that the response of inflation to fiscal deficit may not be symmetric.

The remaining part of the paper is arranged as follows. The next section specifies the theoretical debate. A cursory summary of the relevant literature is reported in section 3. Section 4 narrates the nature of variables and exposition of the econometric method to be employed, followed by result discussion in section 5. Lastly, the paper conclusion and associated policy recommendations are highlighted in section 6.

Theoretical debate

Theoretically, various views have been advocated about the impact of fiscal deficit on inflation. Neoclassical theory asserted a positive relationship between the two through higher money demand. When the income of the economic agents rises, more money is needed to facilitate the transactions due to increased incomes. Demand for real balances increases due to a rise in the level of real income and hence leads to a hike in the price level (Ball, 2017). The Keynesians also provide another channel for a direct association between fiscal deficit and inflation like those of Elmendorf and Mankiw (1999) through aggregate demand augmentation. The collapse of the Bretton woods system in 1971 which resulted in the era of flexible exchange rate regime and the oil price shock of the 1970s led to the breakdown of the celebrated Philips curve hypothesis. This led to the development of Monetarist school and the pioneer of which, Milton Friedman, maintained that inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon and that money supply growth that may result due to deficit financing causes inflation.

The impact of fiscal deficits on inflation has also been discussed in the celebrated work of Sargent and Wallace (1981) in a framework of “monetary dominance” and “fiscal dominance” regimes. The deficit is financed either through bond sales to the public or through the seigniorage created by the monetary authority or by a combination of both. In the case of an independent monetary authority framework, fiscal authority is constrained in the formulation of its policy. In this regime of monetary dominance, the money supply is regulated, and fiscal deficits would tend to be non-inflationary. On the contrary, in a fiscal dominance regime, the regulation of money supply by the monetary authorities becomes less effective and fiscal authorities satisfy the inter-temporal budget constraints through the excess money creation, in the process leading to inflation. While the monetarists ascribe the tag of the monetary phenomenon to inflation, Fisher and Easterly (1990) regarded the inflationary tendencies as being a fiscal phenomenon. Fiscal authorities have often preferred seigniorage to finance the fiscal imbalances, thereby triggering the inflationary pressures.

There is yet another recent theoretical premise arguing for the nature of the relationship between fiscal deficit and inflation, namely the fiscal theory of price level (FTPL), given by Woodford, 1994, 1995, 2001; McCallum, 2001; Cochrane, 2001, 2005; Leeper and Yun, 2006. According to FTPL, the price level in an economy is not determined individually by monetary authorities alone, but complementarity of both monetary and fiscal policies is operative. When the fiscal authorities make an adjustment to the present value of its future surpluses, the price level will rise to lower the real value of debt . In FTPL, fiscal authorities are permitted to choose the surplus or deficit figures, not necessarily conducive for fiscal solvency. Thus, due to the exogenous character of fiscal actions, the endogenous movement of the price level is required to achieve fiscal solvency. The fiscal policy thus becomes a leader and monetary policy a follower, controls only the timing of inflation and with the result, fiscal deficit tends to be inflationary. Minford and Peel (2002), therefore, asserted that price level and fiscal policy are linked through the present value of the corresponding budget constraint . Inflation may not be a result of money creation only, but in a dominant fiscal policy regime, where the fiscal policy is not sustainable and government bonds are considered net wealth, the wealth effects could compromise the objective of price stability irrespective of central bank’s commitment to control inflation (Ramu and Gayithri, 2017).

It is important to note that the association between deficit and inflation is a dynamic one (Lin and Chu, 2013). In a fiscal dominance regime, fiscal deficit provides an estimate of the future and not the current money creation (seigniorage) required for their financing and hence does not lead to current inflation. This is due to the fact that borrowing enables fiscal authorities to allocate the seigniorage inter-temporally and thus, refute the existence of any contemporaneous association. In addition, the short-run association between the two variables can be multiplex (Dornbusch et al., 1990; Calvo and Vegh, 1999), can involve possible feedback of inflation on the fiscal deficit (Catao and Terrones 2005) and hence its direction and strength may not be accommodative to theoretical analogies. Therefore, the empirical examination between these two variables would be analysed from a long-term perspective.

Empirical review

General literature

The issue of inflation has always been at the core of theoretical and empirical debates. Scholars have analysed the inflationary tendencies in various countries with different datasets, different determinants, and different econometric methodologies. So far as the impact of fiscal deficit on the inflation is concerned, Hamburger and Zwick (1981) found the inflationary nature of budget deficit while analysing the United States data for a period 1954-1976. The authors also found a budget deficit more inflationary in the Keynesian regime (1961-1974). However, Dwyer (1982) failed to document any evidence in favour of influence of debt on the money supply and overall price level in the economy. On the contrary, Ahking and Miller (1985) reported the evidence of deficit-Inflation relationships only in some specific periods. Similarly, Darrat (1985) found money growth and fiscal deficit as the significant determinants of increased price levels. Applying a neo-classical framework, King and Plosser (1985) reported the existence of a weak deficit-inflation relationship. Moreover, King and Plosser (1985) failed to uncover any such relationship while examining a mix of 12 developed and developing countries.

Examining the data from 10 developed countries, Giannaros and Kolluri (1986) found the absence of any kind of relationship between inflation, money supply, and fiscal deficit. Similarly, using the data over the period 1952-1987, Protopapadakis and Siegel (1987) also reported the existence of a feeble association between these two variables in another set of 10 developed economies. In addition, inflation is not found respond to debt growth strongly. In another study on 7 industrial economies, Barnhart and Darrat (1988) found the absence of any unidirectional or feedback Granger causality between this inflation and fiscal deficit.

In the case of 17 developing countries and for a time period from 1961 to 1985, De Haan and Zelhorst (1990) found the absence of any evidence in favour of the “fiscal dominance hypothesis” and reported that inflation reacts to deficit only during high inflation episodes. Metin (1998) documented the inflationary impact of fiscal deficit in the case of Turkey. However, analyzing the data on 3 transition economies, Komulainen and Pirttilaä (2002) reported the neutrality of fiscal deficit in explaining the inflationary tendencies in these economies. Similarly, Loungani and Swagel (2001) found a puny association between fiscal balance and inflation in the case of 53 developing countries. However, the relationship becomes stronger in the case of economies with higher average inflation. The authors further reported the non-linear influence of fiscal imbalances on inflation and found that the former affects the latter significantly only when the magnitude of the former is above 5%. Domac and Yucel (2005) while applying pooled probit estimation in the case of 15 emerging economies documented the inflationary role of fiscal deficit. Recently, Nguyen (2015) also reported the evidence of fiscal inflation in the case of eight selected economies of Asia.

Some scholars were interested to examine the deficit-inflation nexus in the case of a mix of developed and developing countries together in a panel setting and reported diversity of results. For instance, Karras (1994) found an absence of any impact of the deficit on inflation in the case of a panel of 32 developed and developing countries. Similarly, examining a panel of 90 countries, Click (1998) reported the absence of any impact of domestic debt on inflation over the period 1971-1990. However, Cottarelli et al. (1998) found the inflationary nature of deficit along with inflation persistence in the case of a mixed panel of 47 countries. Similarly, Laasch et al. (2002) found evidence in favour of fiscal inflation by examining a mixed panel of 94 economies. The study further reported the significant role of fiscal deficit in determining the seigniorage and inflation in case of high inflation periods and in case of countries with high average inflation. Catao and Terrones (2005) examined a data set comprising of 109 countries over a period of 1960-2001 to investigate the dynamic nature of interactions between these two variables. The study documented the evidence of inflationary nature of deficit figures in the case of transition economies and in the economies featured with high episodes of inflation but not in the case of advanced economies and those experiencing lower inflation levels. Similarly, examining the larger data set over the period 1962-2004 for a mixed panel of 71 countries, Kwon et al. (2009) found the positive and appreciable impact of debt growth on the inflation in case of countries plagued with massive debts but, however, the impact is low in remaining cross-sections of the panel. Likewise, Lin and Chu (2013) while analysing the data on 91 countries for the period 1960-2006, found the results more or less like that of Catao and Terrones (2005). More recently, Tran (2018) investigated the asymmetric impact of fiscal balance on the key monetary variables like interest rate, inflation, and exchange rate in the case of four emerging economies like BRIC for the period 1999-2000. The study found the long-run association between fiscal balance and monetary variables in the case of countries like Brazil and India, whereas no such association is found for China and Russia. In addition, the deterioration of fiscal balance is found to have a more powerful and significant impact on the monetary variables than when it improves.

Studies specific to India

The deficit inflation interaction has also been examined in the case of the Indian economy. Sarma (1982), Jhadav (1994) and Ragrarajan and Mohanty (1998) have found the existence of a perennial interaction between fiscal deficit and inflation in both forward and feedback directions. In addition, these studies have reported the fiscal deficit among the important determinants of inflation in India. The outcome of these studies is relevant to the prevailing conditions of that time. With the permanent blockade of ad hoc treasury bills in 1996-97, market borrowings used to finance deficit ceased as an option and mode of monetization was resorted. However, even after accounting for the monetization period of deficit financing in an extended data set analysis, Ashra et al. (2004) reported the absence of long-run association between Reserve Bank credit and fiscal deficit and between money and Reserve Bank credit to the government. The study, therefore, recommended the scrapping of fiscal deficit as a stabilization tool. Using a more recent data set and an updated methodology, Khundrakhpam and Goyal (2009) reported the significant contribution of fiscal deficit in the incremental reserve money creation and overall money expansion, which finally leads to inflation in the economy. Similarly, Khundrakpam and Pattanaik (2010) found the inflationary role of fiscal imbalances. The Reserve Bank of India (2012), also reported evidence in favour of the fiscal inflation in India. Mohanty and John (2015) applied the time-varying structural VAR procedure to analyse the time-varying impact of various determinants of Inflation in India. This study reported the inflationary impact of fiscal deficit. More recently, Ramu and Gayithri (2017) found the inflationary impact of fiscal deficit in India. Through an SVAR approach, the authors have documented the evidence of three transmission channels like consumption expenditure channel, money supply channel and import channel to portray the traverse of the impact of fiscal deficit on inflation. However, no evidence in favour of the interest rate channel is observed.

The above literature survey highlighted certain important points. On average, deficits are reported to be less inflationary in advanced and low inflation countries characterized by sound and credible monetary authorities and less fiscal dominance. However, in developing countries with higher inflation rates and high inflation episodes, the deficits are found to be inflationary. There is an inconclusiveness documented about the impact of the deficit on inflation in general and India in particular. A limitation of the existing literature is that the analytical framework adopted for the empirical exercise is largely symmetric/linear and the possibility of any asymmetric nature of the relationship is omitted. To fill this void, the present study, therefore, is an attempt to analyse the inflationary impact of fiscal deficit in a dynamic and asymmetric framework. Our study, will, therefore, enrich the existing literature along the asymmetric lines.

Data description and empirical methodology

Data description

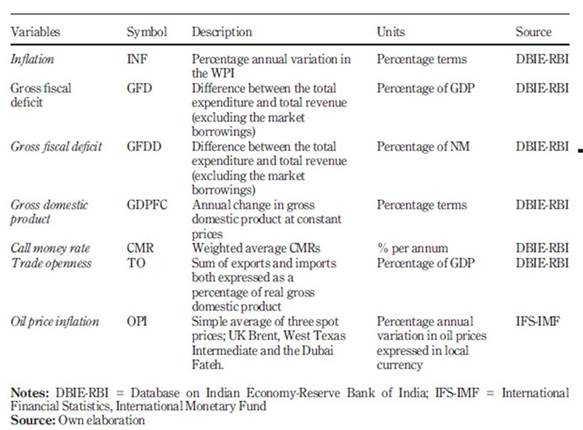

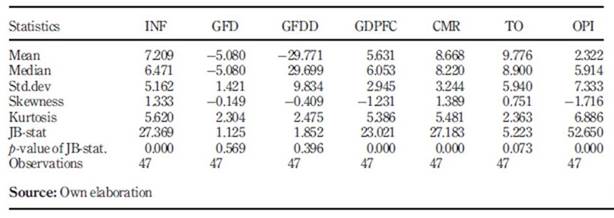

The selection of the variables for the empirical analysis is guided by the prevalent theoretical propositions and the existing empirical evidence. The data set is of annual frequency covering the period 1970 to 2016. The variables include Inflation (INF), Gross fiscal deficit (GFD), Money (NM), Gross domestic product (GDP), real GDP growth rate (GDPFC), Interest rate (CMR), Trade-openness (TO), Exchange rate (EXR) and Oil price Inflation (OPI). The data on all the variables (except OPI) has been taken from Database on Indian Economy (DBIE), Reserve Bank of India website, whereas for OPI we resorted to International Financial Statistics (IFS) from International Monetary Fund. INF is expressed as percentage annual variation in the Wholesale Price Index (WPI). GFD is expressed as a percentage of GDP and following Catao and Terrones (2005) and Lin and Chu (2013), GFDD is also scaled by narrow money (NM) for robustness purposes. GDPFC is the annual change in the gross domestic product at constant prices. NM is represented by the narrow money measure. TO is proxied by the sum of exports and imports both expressed as a percentage of GDP . The average of three Oil price measures in the foreign currency is first converted into rupee terms by multiplying the nominal exchange rate (EXR= ₹/$) of India with the respective oil price figures. Finally, OPI is calculated as the percentage annual variation in oil prices expressed in domestic currency. The inclusion of OPI in the analysis will portray the effect of oil price dynamism and exchange rate movements simultaneously. The definition of various variables is given in Table 1.

Empirical methodology

Causality examination

Time-domain causality

To examine the time domain causality between fiscal deficit and inflation, the study employs the well-known Toda and Yamamoto (1995) test, henceforth (TY) test. In the usual procedure of the conventional Granger causality test, the lagged coefficients obtained through the underlying VAR model are set equal to zero according to Wald’s principle. However, Lutkepohl and Kratzig (2004) cautions about nonstandard limiting distributions of Wald’s test statistic due to the co-integration properties of the VAR model. These nonstandard asymptotic properties follow from the singularity of asymptotic distributions. To do away with the singularity nuisance, the TY test, supplemented the original VAR model with the maximum order of integration of variables. Moreover, the test performs better in case the variables are integrated and possibly cointegrated and the data is used in levels rather than in first differences .

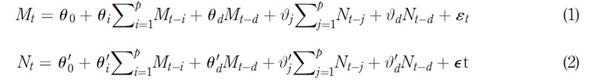

The TY test is performed using the specifications 1 and 2. It is to be noted that the standard Granger causality is based on VAR(k) model, wherein k is the appropriate length of lags of various variables reported by different lag selection criteria. However, in TY procedure, VAR (k + d max) model is estimated. Here dmax denotes the maximum order of integration of the variables suspected in the process. If we set lag length k equal to p and d is reported as the highest order of integration, we proceed as:

M and N constitute the set of variables to be examined for analysis. Here zero restrictions are put to first p parameters in order to test the null of no causality against an alternative one where the causality is supposed to exist. The test statistic is usually referred to modified Wald (MWALD) and follows a 𝜒 2 distribution with a degree of freedom equal to 𝑝 and supposed to be independent of the unit roots and cointegration.

Frequency domain causality

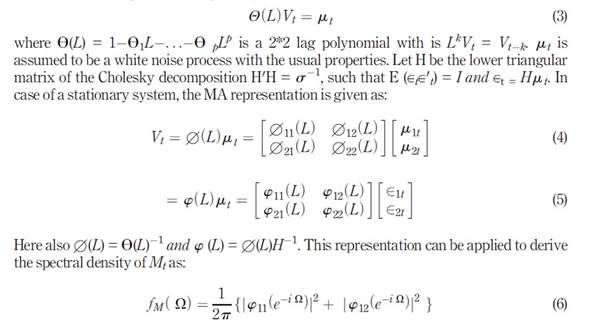

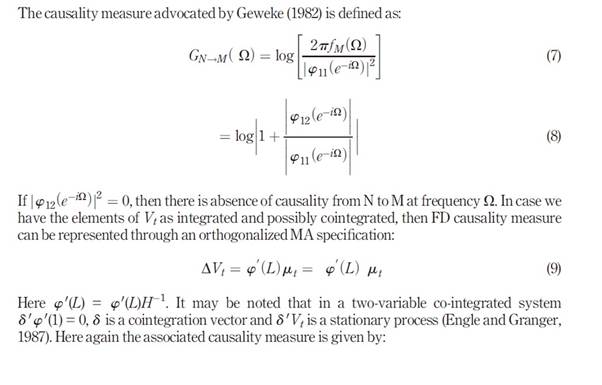

With a view to examining the issue of causality in the short and long-run, the frequency-domain framework is incorporated. Statistically, frequency domain (FD) refers to a domain for the examination of mathematical functions or signals at various frequencies instead of time, wherein a given stationary process is decomposed into a weighted sum of sinusoidal components with a certain frequency (Ω). Though the nature of the definition of causality remains the same for both time and frequency domains, the framework of examination is different. Change of a signal over time is represented by a time-domain graph, whereas the magnitude of a signal within each frequency band over a range of frequencies is connoted by the FD graph. More simply, time denotes the happening of a variation and frequency measures the strength of that variation. Though there are many approaches available in the literature to conduct the Granger causality in frequency domain analysis, we, however, employed the recently developed framework of Breitung and Candelon (2006), hereafter (BC). This approach has the advantage of being applicable to either a stationary set of variables or integrated but not cointegrated (data used in first differences) or both integrated and cointegrated (data is used in levels). In addition, FD analysis eliminates seasonal variations in case the data series used for analysis is short and the methodology accounts for non-linearities and causality cycles i.e. causality analysis at low and high frequencies. Following the Geweke (1982) procedure.

Breitung and Candelon (2006) test between the two variables M and N can be performed through a VAR derived framework as :

Let Vt = (Mt, Nt) be a two-dimensional vector of time series obtained at t = 1. . .., T with a finite-order VAR representation given by:

The F statistic related to Equation 4 follows F (2, T-2p) for Ω ∊ 0,𝜋 . It is to be noted that the causality between the two variables at the low frequency denotes the long-run causality and the short-run causality is represented at high frequency. If the variables are cointegrated then causality at zero frequency connotes long-run causality and in case of stationary variables there exists no such thing like long-run causality, instead, the low-frequency causality implies the explanatory variable is able to predict the low-frequency component of dependent variable one period ahead.

Asymmetric cointegration

Primarily the study examines the existence of a long run cointegration relationship between fiscal deficit and inflation in the case of the Indian economy. There are a number of linear tests available in the literature to check for the existence or otherwise of cointegration. The limitation of these tests is that they assume a symmetrical association among the variables and ignore the possibility of any asymmetry in the nature of the relationship. The scholars like Shin et al. (2014) cautioned about the misleading repercussions of assuming explicitly a linear association among variables and therefore, suggested to take account of possible asymmetries. This development of literature evaluating the issues of non-stationarity and non-linearity ( Psaradakis et al., 2004; Kapetanios et al., 2006) clearly highlights the inadequacy of linear models to allow a more precise statistical inference and to produce authentic forecasts in case of situations featured with positive transaction costs and where policy implications are observed in-sample (Shin et al., 2014).

Doing away with linearities and taking cognizance of possible asymmetries, we applied an asymmetric NARDL model by Shin et al. (2014) for empirical analysis of long-run and short-run asymmetries among variables of interest. It is a convenient approach as it provides a dynamic error correction specification combined with the asymmetric long-run cointegration regression by decomposing a given time series 𝑁 𝑡 into its oppositely signed partial sums (Nt + and Nt -) in order to take account of possible asymmetries. Second, it provides Bounds based test statistic, used to check for the existence of stable long-run association among variables of interest. Third, the method provides graphs of cumulative dynamic multipliers used to trace out the adjustment patterns following the positive and negative shocks to explanatory variables. The model is simple and comprehensive enough to permit any asymmetry switching from the short-run to the long-run or vice versa . Such is the flexibility of this framework that accommodates different specifications for the various possibilities of short-run and long-run asymmetry. Additionally, the NARDL model allows to testing for the hidden cointegration, so that the omitting any relationships, not apparent in a linear framework, is avoided .

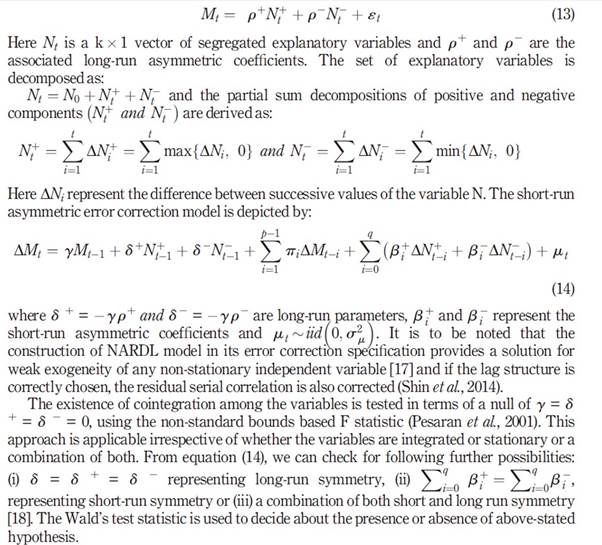

The basic version of the model involves the following specification(13 y 14):

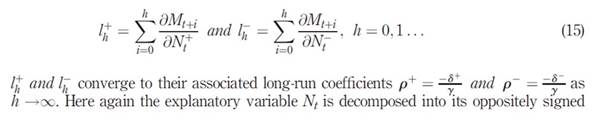

The study finally employs the non-linear cumulative dynamic multipliers to portray the route between disequilibrium position of short period and new long-run equilibrium of the system. The multipliers permit us to find out the asymmetric adjustment patterns following positive and negative shocks to explanatory variables. The diagrams have the important theoretical connotation of providing a way to illustrate the traverse to a new stable equilibrium position following any short-run disturbance from the long-run relationships (Shin et al., 2014). The cumulative dynamic multipliers of 𝑁 𝑡 + and 𝑁 𝑡 − on 𝑀 𝑡 can be evaluated as follows(15):

components around a zero threshold value to portray the behaviour of the dependent variable to these components.

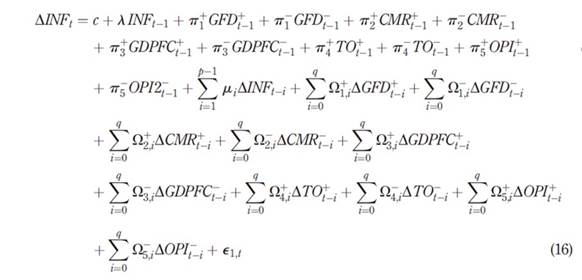

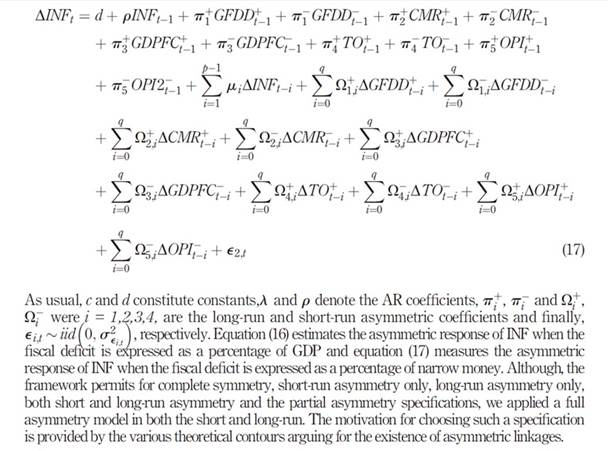

So far as the variables involved in the empirical analysis are concerned, the following nonlinear error correction models based on the error correction specification (14) are estimated.

The inclusion of various variables is strictly in accordance with the existing theory and empirical evidence. While the GFD or GFDD is included according to the various theoretical arguments discussed above. The fiscal deficit is largely considered to be inflationary, although the channels of transmission may assume various routes like the consumption expenditure channel, money supply channel, import channel and the interest rate channel . As a proxy for monetary policy actions, interest rate variable (CMR) is included and inflation is expected to respond negatively to interest rate through the traditional aggregate demand channel. To take account of the possible influence of structural factors , we include real GDP growth rate to act as a surrogate for output fluctuations in the economy.

The increased output growth is expected to lower the inflation by increasing the domestic availability of goods and services whereas a decrease in it escalates the inflationary pressures to denote the dearth of goods and services domestically. Due to the increasing integration of the Indian economy with the rest of the world, trade-openness is also included in the inflation determination equation to test the validity of Romer (1993) hypothesis on India. The hypothesis argues for a negative association between openness and inflation due to the time inconsistency of monetary policy in case of more open economies. Lastly, increasing dependence on oil imports makes it imperative to include the oil price dynamics and exchange rate fluctuations into the domain of empirical analysis. The increased oil prices are expected to trigger inflationary pressures and a fall is expected to lower them, of course depending upon the extent of pass-through. Thus, a combination of factors related to monetary policy, fiscal policy, supply shocks, and external factors are included in empirical exercise for a comprehensive analysis.

Empirical results and discussion

Unit Root Analysis

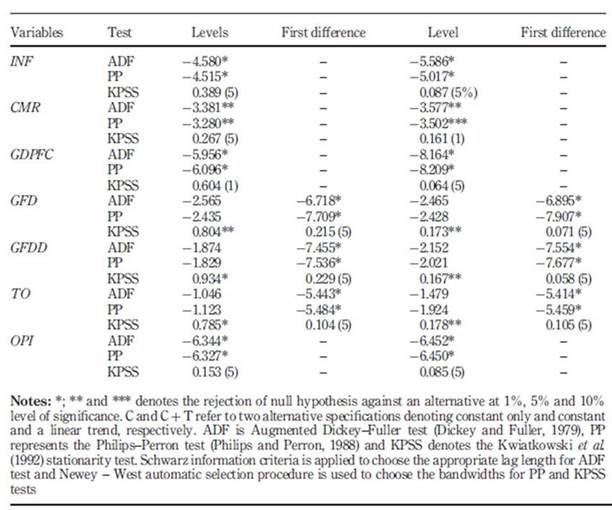

Using the appropriate specifications for each variable in each of the unit root tests mentioned, the results shown in Table 2 report a mixture of stationary and non-stationary variables. INF, CMR, GDPFC, and OPI are found I(0) and GFD, GFDD and TO are found to be I(1) at the level and I(0) at first differences.

Cointegration and causality analysis

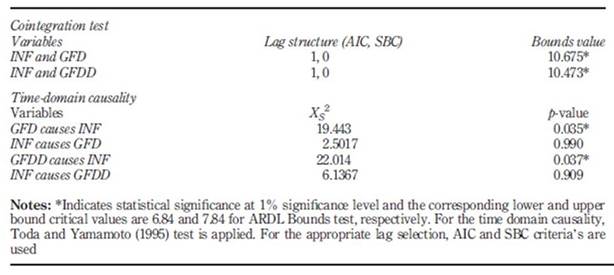

Prior to the causality evaluation, we first check whether the variables of prime interest i.e. INF & GFD and INF & GFDD have any cointegration relationship or not. Since we have a mixture of I(0) and I(1) variables, the autoregressive distributed lag model (ARDL) or Bounds F-test as given by Pesaran and Shin (1998) and Pesaran et al. (2001), would be an appropriate method to apply. As reported in panel A of Table 3, the null of no cointegration is rejected between INF and GFD both expressed as a percentage of GDP and expressed as a percentage of NM. With the confirmation of the long-run association between the two variables, causality analysis in time domain framework is examined through the TY test.

Literature has highlighted that the direction of causality is not only from fiscal deficit to inflation through the various transmission channels, but a feedback causality is also possible. Inflation can both increase and decrease the fiscal deficit. According to Aghevli and Khan (1978) Hypothesis, an increase in inflation reduces the real value of government income and thereby necessitates it to borrow more in order to meet the expenditure requirements. With the resulting deficit rises and is known as the inflation-induced fiscal deficit (Heller 1980). Similarly, excessive inflationary pressures mandate a contractionary policy stance on part of monetary authorities to control it. Higher nominal interest rates (Fisher effect) increase the debt interest payments of the already accumulated debt of the government and thereby trigger further the deficit level. Similarly, according to Olivera-Tanzi effect, higher inflation pressures can also lead to a decline in the volume of tax collection and deterioration of real tax proceeds being collected by the government due to time elapsed between the taxable event occurs and the collection of the tax becomes effective (collection lags) (Olivera, 1967; Tanzi, 1977) . Thus, due to the deteriorated revenue position, deficit increases. Besides the positive association, the inflation and budget deficit also move in reverse direction under certain circumstances. Inflation tax would be a type of tax revenue that leads to a fall in deficit. Similarly, if the borrowing is not indexed to the inflation, any hike in the later will lower the real value of the former through borrowing shocks.

The lower panel of Table 3 indicates that fiscal deficit granger causes inflation in India, but feedback causality is absent. The presence of unidirectional causality and long-run cointegration relationship highlights the inflationary influence of deficits in India. The establishment of the unidirectional causality from fiscal deficit to inflation is in accordance with the results of Ramu and Gayithri (2017).

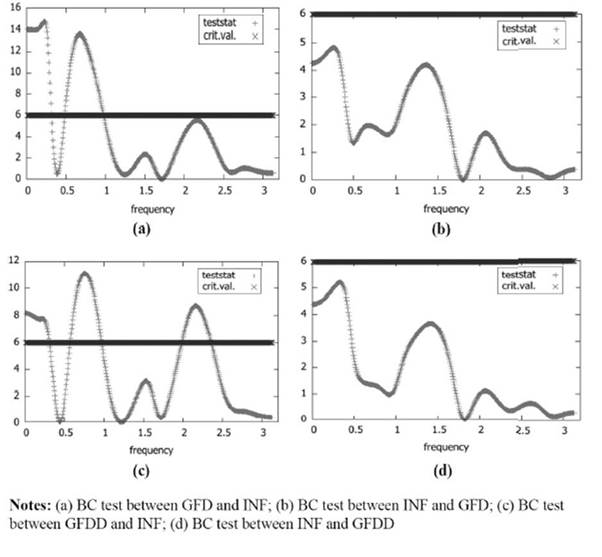

The four parts of Figure 1 (a, b, c and d) portray the causality analysis in a frequency domain framework using the BC test. Part “a” of the figure shows that fiscal deficit causes inflation only at lower frequencies or higher time periods. At the higher frequencies (short run), the deficit is not found to cause inflation in India. Part “b” again provides an illustration of the absence of feedback causality from inflation to fiscal deficit in India at all frequencies. Thus, BC test documents that fiscal deficit need not be inflationary in the short-run since the government can temporarily resort to other sources of financing the deficit instead of excess money creation in the short-run (Sargent and Wallace, 1981; Lin and Chu, 2013). The outcome of this result also validates the intrinsically dynamic nature of the relationship between these two variables. The parts “c” and “d” of the figure provides the results for robustness.

Asymmetry analysis

With a view to providing some insights about the possible asymmetry, if any, exists between the variables, the study applies NARDL model developed by Shin et al. (2014). We include INF, GFD, CMR, GDPFC, TO and OPI variables into the NARDL error correction specification (8). Since none of the variables is I(2), the application of NARDL is justified. In addition, the adopted methodology would also take note of the dynamic nature of the relationship since the specification permits the lags of both dependent and independent variables to influence the dependent variable and also allows for intrinsic dynamic adjustment .

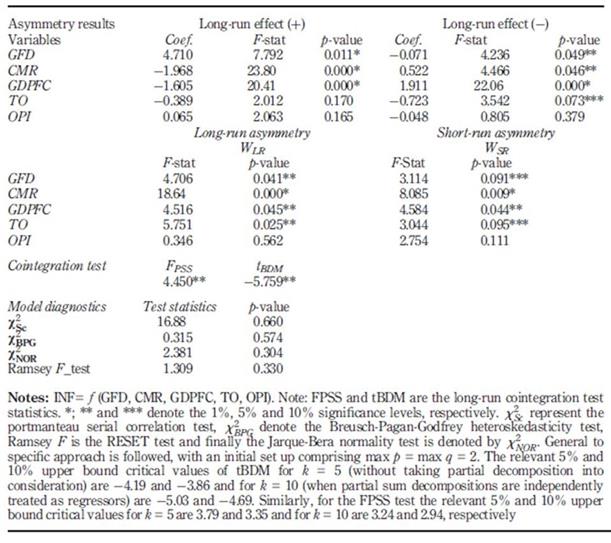

We followed a general to a specific approach for the estimation of the asymmetric ARDL error correction model. We started with max p = q = 2 as decided by AIC and SBC criteria’s, and zero restrictions are assigned to most of the insignificant lags to ensure precision and avoidance of noise into the dynamic multipliers. In this case, as well, the null of no cointegration is rejected like in the case of linear Bounds F-test, since both the tBDM and Fpss tests, as reported at part B of Table 4, are found to be statistically significant at 5% significance level.

Part C of Table 4 reports the necessary diagnostic tests of the estimated model to ensure its stability. The absence of serial correlation is accepted in the case of the Portmanteau serial correlation test 𝜒 𝑆𝑐 2 , heteroskedasticity in the case of Breusch-Pagan-Godfrey test 𝜒 𝐵𝑃𝐺 2 , Ramsey RESET test (Ramsey F-test) validates the structural specification of the model and finally, presence of normality is accepted in the Jarque-Bera test of normality 𝜒 𝑁𝑂𝑅 2 . With the detection of long-run association, we proceed to examine whether it is symmetrical, or some asymmetry is involved. Wald’s test with a null of symmetrical association between the variables is tested against an alternative of asymmetrical one. The (WLR) and (WSR) test statistics are shown in part A of Table 4. The results document that except between INF and OPI, presence of an asymmetrical long-run association is established between INF and all other explanatory variables. The short-run asymmetry is also reported among the same pairs of variables and the null of symmetric association cannot be rejected again in case of oil price inflation.

The long-run coefficients of the inhabited relationship of various variables with the inflation are reported in panel A of Table 4. The establishment of a long-run direct association between the fiscal deficit and inflation provides empirical support to the projections of Khundrakpam and Pattanaik (2010) and is in line with the findings of Rangarajan et al. (1989); Ramu and Gayithri (2017); Tran (2018). The surge in money supply (due to increased fiscal deficit and capital inflows) and the narrowing down of negative demand gaps in the economy provide a manifestation of inflationary role of fiscal deficit in India (Khundrakpam and Pattanaik, 2010). The positive impact of fiscal deficit on the inflation of India can be attributed to the transmission channels like the consumption expenditure channel, money supply channel, import channel and the interest rate channel and according to the theoretical arguments of Keynesians, Neo-Classicals and Monetarists. In fact, Ramu and Gayithri (2017) have exclusively tracked the first three of these transmission channels in the case of India. Emerging countries like India featured with high fiscal deficit and public debt stocks are more exposed to inflationary pressures (Tran, 2018). Therefore, owing to their less fiscal space as may be needed for sustainability, these economies are vulnerable to higher default risks.

The signs of positive and negative coefficients are according to theory and both are statistically significant. However, an increase in fiscal deficit is found to be more inflationary and the decrease in it affects inflation with a lower magnitude. In other words, the impact of fiscal position deterioration is more pronouncing and that of any fiscal improvement is milder or sluggish. Though it is not within the scope of the present study to provide the underlying reasons for the asymmetric response of inflation to positive and negative changes in the fiscal deficit, however, the relevant theoretical underpinnings are worth mentioning. The possible asymmetry of fiscal deficits on inflation in the case of India can be explained through the existence of liquidity constraints, consumption-investment downward inflexibility, and the downward price stickiness. Due to the existence of liquidity constraints as reflected through less developed credit markets and a large portion of the population without adequate purchasing power in India, any increase in fiscal deficit would lead to an exacerbated increase in aggregate demand because of additional purchasing power with the individuals with limited liquidity hitherto and also enable individuals without constraints to feel wealthier. Hence, the impact on inflation would be relatively higher. In case the deficit is reduced, people find it difficult to lower the consumption levels (Ratchet effect) drastically along with investment irreversibility, leading only to a marginal decline in demand conditions and hence a lower effect on inflation is observed. The lower impact of reduced fiscal deficit on inflation can also be explained through downward price stickiness. Producers are usually hesitant to price and wage reductions in order to avoid worker-employ conflicts, secure the worker morale and secure some degree of price-setting power even in a supply-constrained economy (Mohanty and John, 2015; Barnichon et al., 2017). Thus, the effect of contractionary fiscal action in-terms of a decline in deficit spending has a lower effect on inflation.

Coming to the impact of monetary policy shocks as surrogated through call money rate of interest, we found that the inflation and interest rate are negatively related wherein a contractionary policy shock lowers it and an expansionary one raises it. The established negative association can operate through the conventional aggregate demand channel. However, the contractionary policy stance is found to be more effective than the expansionary one, signifying the asymmetric influence of monetary policy actions on the inflation of India. The reason for this asymmetry can be ascribed to the behaviour of demand conditions due to the changing outlook of firms and consumers, the binding liquidity constraints and the downward price stickiness under alternative monetary policy stances (Morgan, 1993; Barnichon et al., 2017). The changing outlook of firms and consumers could result in the asymmetric impacts, if the magnitude of pessimism is relatively high during economic downturns than they are optimistic during expansions, or if the business and consumer confidence matters more during recessionary conditions . As related to the credit constraints, tight monetary policy would be more effective than an easy one if the former makes banks less willing to lend to some riskier (subprime) borrowers. An increase in interest rate by the central bank leads to an upsurge in lending rates of commercial banks due to the shifting of increased costs to the borrowers. The high lending rates could, in turn, increase the chances of borrower’s default and as a result, banks become more risk-averse and very choosy in the credit supply and hence make them liquidity constrained. This leads to a lower level of investment, a reduction in household consumption i.e. a reduction in demand conditions and hence an appreciable fall in the price level (Barnichon et al., 2017). On the contrary, a cut in the interest rates through an easy policy action eliminate the credit constraints. However, if the demand for credit is lacking during an economic downturn, slacking the liquidity position may not necessarily augment the borrowings and higher spending. Therefore, the impact on inflation would be feeble. The substantial reduction of inflation due to the interest rate hike can also be explicated through the money supply channel. An increase in interest rate by the central bank leads to a rise in prime lending rate, a decline in credit supply, a fall in money supply via money multiplier process and finally to a lower level of the price level. On the other hand, a decrease in the interest rate during the retarded economic conditions will not necessarily lead to borrowing and spending augmentation of all economic agents in the economy, the effect of expansionary policy stance on inflation will, therefore, be relatively lower (Barnichon et al., 2017).

The impact of output growth and decline as represented by the positive and negative-sum components of GDPFC is well according to the theory, but asymmetry is reported. Negative growth in output is found to increase the inflation relatively by a higher magnitude than the positive growth is found to reduce it. A decline in the output indicates the presence of supply constraints and given the demand conditions (if not increasing) the impact on price level will be higher. On the contrary, an increase in output growth cannot decrease the prices drastically due to the presence of producer’s price-setting power to some extent. Thus, in a supply-constrained economy, downward price rigidity leads to the asymmetric impact of output changes on inflation.

As regards the trade-openness, although an asymmetry is reported, the signs refute the validation of Romer (1993) hypothesis in the case of India. Specifically, the coefficient of TO+ is -0.389 and that of TO- is -0.723. The former is statistically insignificant, and the latter is significant. The insignificance of TO+ may be due to its ex-post measurement of openness only and lacks the ex-ante measurement. The negative component is significant, however, and the sign establishes a direct association between these two variables. The direct link in the case of India is in line with the inflationary impact of outward orientation for developing countries (Jalil et al., 2014, Ajaz et al., 2016).

Finally, as related to the impact of oil price inflation, though signs are theoretically correct, yet both the positive and negative coefficients are weak and statistically insignificant. The possible explanation for such insignificance at the segregated asymmetry level is that the global oil prices have been converted to domestic oil prices by multiplying the former with the nominal exchange rate of the country concerned. The movements of the two variables, global oil prices, and exchange rates may not always be reinforcing but some counter-movements are also possible. There may be a fall in global oil prices, but due to the increased demand from the country at a lower global price, its exchange rate depreciates and the initial effect of declining oil prices will now get negated through increasing exchange rates and thus the overall influence may be insignificant. In the case of India, the depreciation of rupee more than offsets the favourable effect of the marginal decline in global commodity prices on domestic inflation (Reserve Bank of India, 2013).

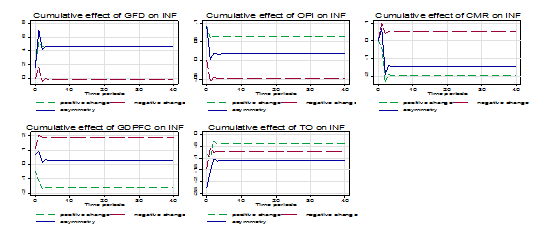

Cumulative dynamic multipliers

Figure 2 plots the dynamic effects of positive and negative changes in the fiscal deficit, interest rate, output growth, trade openness and oil price inflation on the inflation of India. The blue line indicates the line of asymmetry and the value of this line at any given point measures the extent of asymmetry at that point. Figure 2 replicates all the results reported in Table 4, thus confirming the validity of the above discussions. In the case of fiscal deficit, asymmetry is stronger from the positive change and asymmetry persistence is observed even in the long-run. As related to the interest rate shocks, contractionary policy shock is more influential than the expansionary one and the asymmetry is observed in both the short and long-run. Similarly, expansion in output growth declines inflation relatively by a lower magnitude than the increase in inflation is caused by output decline. Finally, in the case of oil price inflation and trade openness, we found the same phenomenon as reported in Table 4. However, the coefficients associated with a positive change in trade openness and with both positive and negative changes in case of oil price inflation are statistically insignificant. Moreover, it takes around more than a year on average to reach to new equilibrium position following any short-run disturbance.

Extensions

The robustness of results is provided by using the fiscal deficit as a percentage of narrow money in an economy as the key variable of analysis. Table 5 and Figure 3 reflect almost a mirror image of Table 4 and Figure 2 and therefore prove the robustness of results .

Although, the study has attempted to explore the asymmetric nature of the relationship among selected variables, however, certain caveats to this investigation are warranted and introspection into these caveats may provide scope for further research in the area. To start with, a more structured analysis with robust theoretical underpinnings may enhance the understanding and findings of this study. Second, on the whole, the unavailability of data for sufficiently longer periods of time acted both a challenge and hindrance for the exploration of a more comprehensive analysis. Although, the asymmetries have been observed in the empirical exercise with respect to the response of inflation to various macroeconomic variables, and the probable theoretical reasons were advocated, however, identification of exact transmission channels of asymmetry would enrich the analysis.

Conclusion

Higher inflation has always been considered as a growth retarding factor and a means of reducing the welfare standards of common masses. Therefore, maintaining a stable price level featuring a low inflation rate has remained a high priority objective of macroeconomic management of various economies including India. Among the many factors fuelling the inflationary tendencies in an economy like monetary shocks, structural shocks, demand shocks, external shocks, and demographic changes, the issue of inflation has also been found to be related to fiscal policy decisions of the government. The primary purpose of the study is to evaluate the inflationary tendencies in India particularly from the fiscal point of view. We examined the causality between fiscal deficit and inflation in a time domain and frequency domain framework. We found unidirectional causality running from fiscal deficit to inflation in case of time-domain analysis and no feedback causality is reported. However, in the case of frequency domain design, causality from fiscal deficit to inflation is found at low frequencies only, i.e. no short-run causality is established and hence dynamic nature of the relationship between the two variables is justified. Using the NARDL model, we examined the nature of association in an asymmetric framework. The results document the existence of an asymmetric long-run direct association between fiscal deficits and inflation. The outcome of this result is an indication of the inflationary role of fiscal deficit in India. However, the increase in the deficit is found to be more inflationary and the decrease in fiscal deficit is found to affect inflation with a lower magnitude. The possible asymmetry of fiscal deficit on inflation can be explained through the existence of liquidity constraints, consumption-investment downward inflexibility, and the downward price stickiness.

The other control variables used in the empirical exercise also reported the theoretically plausible results. Contractionary monetary policy action is found to be more effective than the expansionary one, signifying the asymmetric influence of monetary policy on the inflation of India. Similarly, in a supply-constrained economy with downward price rigidity, we found an asymmetric impact of output growth and output decline on inflation. As regards the trade-openness, although an asymmetry is reported, the signs refute the validation of Romer (1993) hypothesis in the case of India. Finally, the impact of oil price inflation on inflationary pressures is according to theory, but the coefficients are devoid of statistical significance.

The results documented above justified the application of NARDL into the empirical exercise. Thus, instead of assuming the linear nature of model specification (with the associated possibility of inappropriate policy conclusions), we proceeded with a well behaved and theoretically supported non-linear specification to take cognizance of the dynamic nature of the relationship and that of observed asymmetries. These results indicate some important policy recommendations. Fiscal consolidation strategy should be executed in an appreciable manner to achieve sound fiscal health and lower inflation. The disciplined fiscal strategy would also be imperative for an effective monetary policy. Monetary authorities should possess noticeable credibility to manage the macroeconomic system and policy stances should be implemented according to requirements of the economy. Growth in the output should be encouraged to have two-fold benefits to the economy – reducing inflation on the one hand and fiscal deficits on the other .