I. Introduction

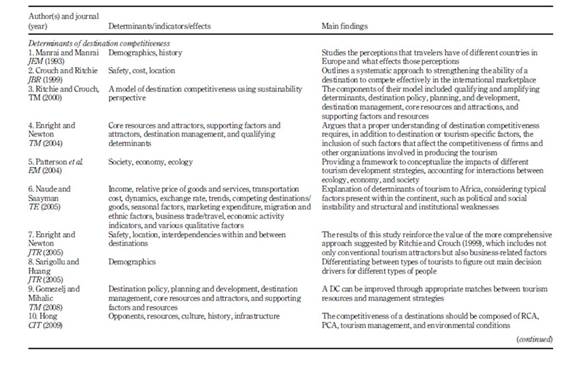

Destination competitiveness (DC) has been studied from a variety of perspectives in tourism literature. Crouch (2011) identifies three broad research streams related to the topic of DC. The first stream deals with the assessment of the competitive position of a specific destination for a specific type of tourism activity, for example, cultural tourism in Toronto (Carmichael, 2002). The second research stream relates to the assessment of the competitive position of a destination on a particular performance attribute; for example, the marketing of a tourism destination (Buhalis, 2000). The third research stream covers the general models and theories of DC (Crouch and Ritchie, 1994, 1995, 2006; Ritchie and Crouch, 1993, (Ritchie and Crouch, 2000, Ritchie and Crouch (2003, Ritchie and Crouch (2010).

Ritchie and Crouch (2000) developed a model of DC using sustainability perspective. Set in the global (macro) environment and competition (micro) environment, the components of their model included qualifying and amplifying determinants, destination policy, planning and development, destination management, core resources and attractions and supporting factors and resources. Cucculelli and Goffi (2016) extended the model developed by (Ritchie and Crouch, 2000by introducing and testing the effects of a set of indicators related to the sustainability of the DC. The data were generated from several small “destinations of excellence,” namely, destinations which had received national and international awards. Findings of the study support the positive effect of sustainability on DC.

Aral-Tur and Kozak (2015), in their book, develop insights on destination management from a variety of perspectives. The book consisting of 15 chapters covers three main areas. These are factors affecting DC; environment, including issues such as climate change; and sustainability of destination. The book has interdisciplinary perspective covering fields of economics, geography and marketing, etc. In our analysis of determinants, indicators and effects of DC presented in this paper, we use an interdisciplinary approach as well, particularly related to the determinants of DC, where 12 environmental factors are identified as determinants of DC.

Boes et al. (2016) push the idea of smart cities enhancing DC to improve quality of life for residents as well as tourists. The authors propose that information and communication technologies (ICT), together with social capital supported by human capital, innovation and leadership are core components of smartness. Boes et al. (2016) use service-dominance logic as the underlying theoretical approach for understanding the value co-creation process at the core of smart cities initiative and provide a comprehensive framework to demonstrate the way smartness can enhance DC.

The subject of determinants and indicators of DC has also received a lot of attention from researchers. Notably, Dwyer and Kim (2003) developed a model of main elements of DC. They also identified several indicators of DC. Other researchers have examined determinants and indicators in the context of country-/region-specific studies (Enright and Newton, 2004, 2005; Gomezelj and Mihalic, 2008; Kozak and Rimmington, 1999).

The topic of DC has evolved. Its predecessors were the topics, such as the destination image, destination development, destination planning, etc. While these predecessor topics are still in use for research, DC has evolved as a comprehensive topic. Nevertheless, it is worthwhile to look at the elements, which were previously included in the predecessor topics. For example, the topic of destination development included natural resources, government policy, etc. Considering this, we think that all aspects of a destination’s environment play a critical role as the determinants of its competitiveness. To the best of our knowledge, a comprehensive study of all environmental elements and their impact on DC has not been studied in the extant literature on DC until now.

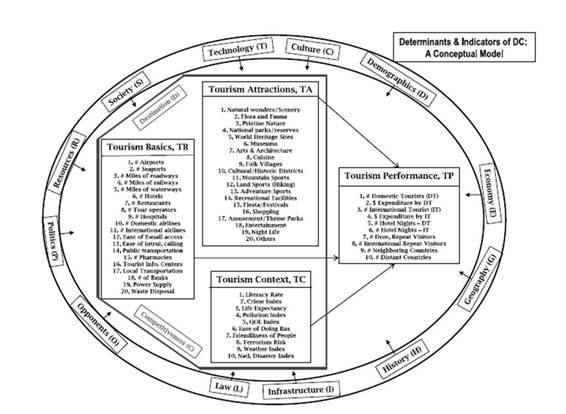

As regards the indicators of DC, early on, Manrai and Manrai (1993) investigated the image of 20 European countries using field surveys. Their findings revealed three broad indicators, namely, Attractions, necessities (later called “Basics”) and Environment (later called “Context,” including safety, literacy, etc.). Subsequent research studies on destination image and destination development and competitiveness also supported these three factors (Armenski et al., 2017; Assaf and Josiassen, 2011; Crouch, 2011; Dwyer and Kim, 2003; Kozak and Rimmington, 1999.) Thus, based on the findings of Manrai and Manrai (1993and subsequent research in the tourism field, we propose the Tourism A-B-C (TABC) model with its elements being indicators of DC. In this TABC model, in which A stands for tourism attractions (TA), B stands for tourism basics (TB) and C stands for tourism context (TC). The TABC model has evolved over nearly a quarter of a century and includes critical considerations that tourists take into account in their destination choice. We compare TABC model with other indicators of DC in the extant literature and conclude how TABC is relatively simple yet a better predictor of tourism performance (TP). Some possible measures of TP are number of domestic tourists, number of international tourists and expenditures by tourists, etc.

We review research, both on the determinants and indicators of DC, and develop 12 propositions and a conceptual model of DC in this paper. The determinants are the variables and factors which make a destination competitive and indicators are the variables and factors which are used to measure the competitiveness of a destination. Our model incorporates two critical factors discussed above which have so far not been parts of DC research. These are: a comprehensive analysis of environmental factors as determinants of DC and use of A-B-C model as the indicator of DC.

The paper is organized into seven sections. In Section 2, we review the literature on DC covering both its determinants and its indicators. In Section 3, we introduce various environmental variables and how they affect DC as its determinants. Next, in Section 4, we introduce the TABC model identifying items included under the A-B-C categories and how these, in turn, are affected by the environmental variables. This section also discusses how TABC variables jointly affect TP. Section 5 presents our conceptual model with environmental variables as the determinants of DC and TABC as indicators of DC. Section 6 discusses the findings and the managerial implications of this research. Finally, Section 7 discusses directions for future research.

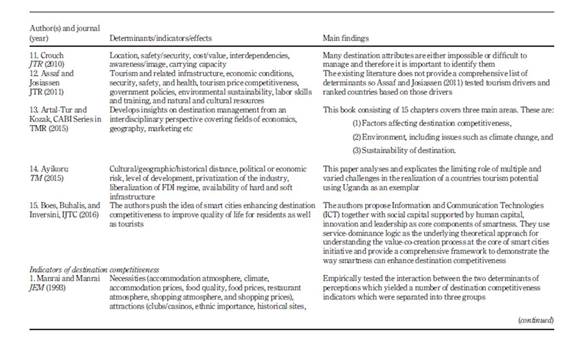

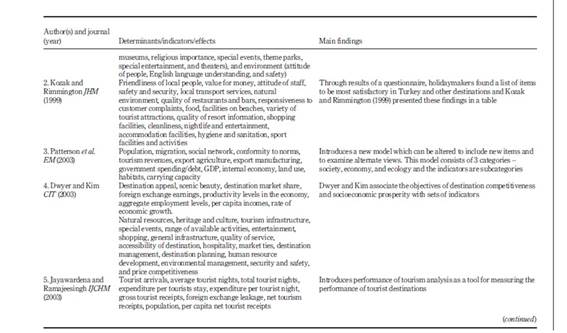

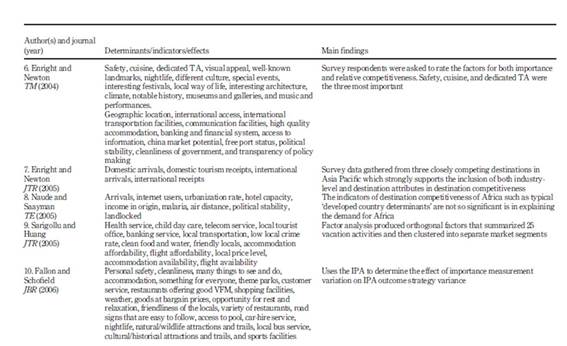

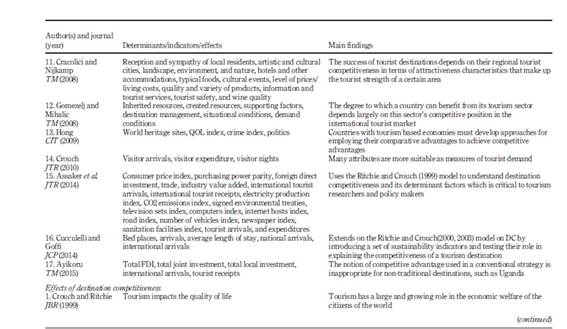

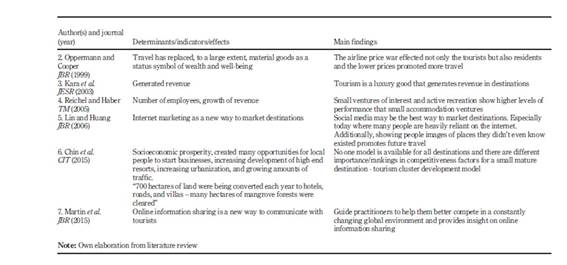

2. Literature review

Many articles that have been previously published classify destination management as a key indicator of TP, which determines the level of DC. Ritchie and Crouch (2010) find that destination management is a key indicator of DC in their model of DC and sustainability. When drawing conclusions based on a survey of CEOs of destination management organizations (DMOs), we feel that the results will be biased toward the importance of destination management. While destination management is vital to repeat tourists and sustainability, it does not fully capture the comprehensiveness of DC. As international business and relations become increasingly more complex, there is a need to find ways to market destinations more effectively and yet simply. The TABC model, introduced by Manrai and Manrai (1993), focuses on essential benefits tourists look for in a destination. These indicators of DC are comprehensive yet simple. The design of the TABC model goes back to Maslow’s (1943, 1987) theory of human motivations. The very first item in the pyramid is physiological needs, food, water and shelter. That would signify that hotels, restaurants and other sources of food and water, as well as various options for accommodation, would be of utmost importance, there being a basic need of someone traveling abroad. Second, Maslow’s (1943, 1987) theory on the hierarchy of needs points to safety and security. Safety and security would, therefore, be the next important thing. Making sure tourists feel safe is many times related to natural disasters, crime and sicknesses. These contextual things that cannot be fully controlled but are still major factors in determining DC. Finally, the last three tiers of Maslow’s need hierarchy pyramid are social needs, esteem needs and self-actualization. These categories indirectly showcase the tourism attractions. This includes anything that may draw the tourist to engage in further research of a certain destination. Interest is sparked in a destination when there are unique attractions, such as natural wonders, world heritage sites, cuisine and festivities. Once a competitive advantage has been established, then destination management and sustainability become important factors in maintaining competitiveness. The model that Manrai and Manrai (1993 introduced allows those countries which are not very well developed to have a competitive position.

2.1 Determinants of destination competitiveness

The determinants of DC as found in the literature are, overwhelmingly, safety, core resources, cost, destination management, supporting factors and qualifying determinants. Many DC articles use the Ritchie and Crouch (2010) model. However, many other determinants are found in other research studies. Hong (2009) introduced opponents, resources, culture, history and infrastructure as determinants. Patterson et al. (2004) include society and economy as determinants. Demographics are also a key determinant (Sarigollu and Huang, 2005). Both Ritchie and Crouch (2010model and the tourism cluster development model (Kim and Wicks, 2010) for global competitiveness do not adequately express all these determinants. Instead, they focus on DMOs, destination image and destination policy. While this is all vital in the long run to enhance a destination’s competitive position, it does not capture the basic idea of DC. Furthermore, by the exclusion of destination management and other such business-related determinants, we can level the playing field between developing countries and developed countries. This is important in today’s global economy as many developing countries are breaching into the tourism sector.

2.2 Indicators of destination competitiveness

The indicators of DC are numerous. Many studies use several categories of indicators to figure out which destinations are the most competitive. Tourist arrivals and tourist receipts were the top indicators for DC. Sarigollu and Huang (2005) offer many indicators including telecom service, health service, local tourist offices, banking services, local transportation, low local crime rate, clean food and water, accommodation availability, flight availability and local price level. Fallon and Schofield (2006) introduce even more indicators. These include, such as things to see and do, theme parks, customer service, restaurants offering good value for money, shopping facilities, a variety of restaurants, road signs that are easy to follow, nightlife, local bus service, cultural/historical attractions and trails and sports facilities. To quantitatively measure DC, TP indicators are used. Jayawardena and Ramajeesingh (2003) introduced a tourism analysis tool to measure performance, which included, tourist arrivals, average tourist nights, total tourist nights, expenditure per tourists stay, expenditure per tourist night, gross tourism receipts, foreign exchange leakage, net tourism receipts, population and per capita net tourism receipts. Indicators in this sense can be defined as characteristics of a destination which add value.

2.3 Effects of destination competitiveness

As transportation becomes ever more affordable and locations become increasingly more accessible, tourism destinations are everywhere. Tourists, therefore, have a much larger choice, and every destination wants their share of tourist revenues. In many destinations, the introduction of the tourism sector has increased the quality of life (Ritchie and Crouch, 2000). Tourism introduces new jobs which increase revenue and the number of employees (Reichel and Haber, 2005). However, increased socioeconomic prosperity is not the only effect of DC. The increasing amount of tourists also leads to growing amounts of traffic and increasing development of high-end resorts. The increased amount of foreign direct investments (FDIs) and Transnational Corporations exploit natural resources for profit and in some instances do away with natural resources that aren’t viewed as favorably to tourists. For example, in Bali, “700 hectares of land were being converted each year to hotels, roads, and villas” of which many hectares were mangrove forests (Chin et al., 2014). As a result of the destruction and increased traffic, many locals have a negative image of tourists. On the other hand, locals also view tourists positively due to the increased revenue that they bring.

A newer model is needed to encompass all determinants and indicators to understand DC. Many articles only cover a few main determinants, whereas the model by Manrai and Manrai (1993) provides more comprehensive coverage. This model is necessary not only for researchers but also for DMOs and the enhancement of destination image.

3. Environmental determinants of destination competitiveness

Many environmental factors affect a destination’s competitive position. These factors will be broken into 12 parts and discussed in further detail.

3.1 Society

As defined by Patterson et al. (2004), society comprises population, migration, social networks, pride of place, subsistence practices and employment. Many of these can overlap with other environmental factors as well. A well-rounded society, therefore, has a positive influence on TP. Kastenholz et al. (1999) identified opportunities for socializing as a dimension of rural experiences. Many tourism attractions promote socializing, such as cuisine and nightlife. In today’s world, many people often go to restaurants not because they are hungry, but because going out to eat is an opportunity to socialize. The same goes for nightlife. Increasingly, tourists opt for hostels not only because they are more price-sensitive but because those who travel alone can meet others at the hostel lobby or bar. Meininger, a hostel group that started in Berlin, Germany, has games and a bar specifically for tourists to socialize. Referring back to Maslow’s (1943, 1987) hierarchy of needs, socializing is important, as it is a mix between belongingness and esteem. As Ritchie and Crouch (2003) argued: “The most competitive destination produces societal prosperity.” It is therefore proposed that:

P1: A prosperous and well-rounded society with opportunities for socialization favorably influences destination competitiveness.

3.2 Technology

Technology is constantly changing, and all countries do not have the same level of technological innovations. Hong (2009) categorized operation mode innovations, special events creation and electronic information resources as technological innovations. Salzburg, Austria, a large city that struggles with pollution and traffic, has created an extremely efficient and environmentally responsible public transportation system called the O-bus system. The implementation of this system reduced the pollution index and made getting around Salzburg much easier (Salzburg-ag.at).

Special events attract tourists to certain destinations and therefore affect the tourism attractions. Belgium’s music festival, Tomorrowland, sells 180,000 tickets within the first hour. The creation of this special event draws thousands of international tourists to Belgium each year.

Electronic information resources are especially important for business travelers. Such basics as having e-mail access and international calling are important. In many countries, such as the USA, Great Britain and many other developed countries, it is “normal” to regularly access your e-mail from a smartphone or make calls back to home. However, tourists traveling to developing countries and rural cities will have to give up these luxuries.

The above discussion suggests that technology affects tourism attractions, TB and TC, the three components of DC. It is therefore proposed that:

P2: Level of technological developments favorably influences destination competitiveness.

3.3 Culture

Culture has been defined as a core resource by Ritchie and Crouch (2010). The cultural heritage of a destination is crucial for long-term prosperity and helps to strengthen the residents’ sense of place and civic pride (Chu and Uebegang, 2002). The prouder the residents are of their hometown, the more willing they are to share their homes with tourists. Tourists desire to experience new or different cultures. By traveling, tourists have the opportunity to put themselves in other people’s shoes. This allows them to forget their problems and stress and see things as locals would do. Just by having a unique culture, a destination has a competitive advantage. Culture can also influence festivals, art, architecture, and cuisine. In India, the cow is sacred, and therefore, most dishes will not include beef. When the Habsburg family was able to take control of Spain, the architecture changed. Modern Spanish houses were not built to withstand weathering as the climate in Spain was not brutal. However, in Austria, the Habsburgs hometown, the buildings were made differently to withstand their extreme climate. When walking through the city of Madrid, these architectural differences can easily be seen by strolling tourists. Culture is an extremely complex subject encompassing all aspects of human life. More unique and varied cultural experiences make a destination more attractive to tourists. It is therefore proposed that

P3: Diversity and uniqueness of cultural experiences favorably influence destination competitiveness.

3.4 Demographics

Demographics such as the literacy rate, crime index, religion, and ethnicity can all play a part in the decision making the process for tourists. A destination that has a low literacy rate and a high crime index is likely to have a less competitive position compared to countries with high literacy rates and low crime indexes. Demographics, as stated by Ritchie and Crouch (2010), are a macro-environmental factor. Furthermore, it is becoming more and more important to target specific segments of tourists for different destinations. For example, many young tourists could be categorized as adventurers while older tourists are more interested in relaxation. As McKercher et al. (2006) stated, “Destinations serve different roles for tourists and, consequently, tourists consume destinations differently.”

While destinations try to position and attract certain categories of tourists, the basic concern tourists have about foreign travel in today’s world is safety and crime rate. Thus, having demographics supporting the image of a destination as a safe place is the first and foremost importance to tourists. It is therefore proposed that:

P4: Demographics supporting safety and security will have a favorable influence destination competitiveness.

3.5 Economy

Having a strong and stable economy is vital for attracting tourists, and attracting tourists is vital to improving small economies. With tourism often come FDI and joint ventures which allow developing countries to expand their economy and in return attract even more tourists. An economy is constantly changing, and there are many indicators of a strong economy such as consumer price index, purchasing power parity, foreign direct investment, trade and industry value added (Assaker et al., 2014). It is also common to see that destinations with strong economies have a greater competitive advantage. The USA has the second largest economy and is ranked number one based on its DC score (Assaker et al., 2014). It is therefore proposed that:

P5: Strong and stable economy favorably influences destination competitiveness.

3.6 Geography

Geography may be the largest player in tourism attractions. A destination’s geography determines its landscape, climate and flora and fauna. Geography has to do with location, and according to Ritchie and Crouch (2010), the location has much to do with its ability to attract visitors. A destination’s geography includes everything that comes with a certain geographical position such as flora and fauna, wildlife native to the area and nature. Destinations that have mountains target a different set of tourists than destinations that have beaches. Geography is a key player for tourists looking for different types of attractions. Thus, it is proposed that:

P6: Geographical diversity and attractions favorably influence destination competitiveness.

3.7 History

History can either improve or worsen a destination’s competitiveness. For example, Uganda was, at various times, entangled in numerous civil wars, which left its inhabitants dehumanized and dispossessed of human rights, dignity, skilled human resources and confidence (Ayikoru, 2015). This led to a negative image of Uganda and a poor position to compete for tourists. On the other hand, historical attractions have been a core attractor for some locations, such as Machu Pichu in Peru. History is an important factor in DC. It allows destinations to have a rich culture and significant artifacts. However, a negative history that is seen to be repetitive or still have impacts on the society can tarnish the reputation of the destination. Thus, it is proposed that:

P7: History has a profound effect on destination competitiveness. Rich cultural legacies and monuments favorably influence destination competitiveness, whereas political turmoil, wars, etc. negatively influence destination competitiveness.

3.8 Infrastructure

Infrastructure is a vital influence on TB. Highways, railways, bus services, airports and ferries are important in getting tourists to and from desired points of interest (Ritchie and Crouch, 2010). Infrastructure makes a location accessible to tourists, and therefore, countries with well-developed infrastructure have better TP. Well-developed airports, seaports, roads, railways and waterways allow tourists to move conveniently throughout a destination. Infrastructure can also improve as TP increases. More companies are willing to make foreign direct investments in a destination that has promise and this, in turn, can improve overall infrastructure in the destination. Thus, it is proposed that:

P8: Developments in infrastructure positively influence destination competitiveness.

3.9 Law

Laws change from country to country; however, drastic changes in law may dissuade tourists from visiting certain destinations. For example, in Uganda, lawmakers moved to legislate against homosexuality, resulting in international criticism and condemnation (Ayikoru, 2015). Also, following laws in certain countries may drastically change a tourist's current lifestyle which would further dissuade them. In many Middle Eastern countries, women cannot travel alone and must cover their heads. Recently, Otto Warmbier was sentenced to 15 years of hard labor for trying to steal a propaganda poster from his hotel in North Korea. The punishment that he received was drastically different from what the punishment would have been in the USA. Thus, it is proposed that:

P9: Drastic laws of a country negatively influence destination competitiveness.

3.10 Opponents

The attractions in neighboring countries can affect a country’s TP. Thus, the countries with similar tourism attractions must work harder to compete with each other. Furthermore, having opponents within a destination allows a competitive environment to emerge. Quality of products will rise and prices will lower. In the article written by Oppermann and Cooper (1999), it was argued that the effect of airline price wars increased the amount of outbound travel. This was due to the influx of lower-priced airlines entering the market and bringing the airline price down. Not only do competitors lower prices but the quality of products and the number of choices increases. This, in turn, increases the quality of life of the residents as there are more jobs and better products. Thus, it is proposed that:

P10: Opponents (competitors) favorably influences destination competitiveness.

3.11 Politics

An unstable political system frightens tourists coming from stable political economies. It infringes on tourists’ safety and security, which is the second tier on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. For example, most countries that participate in a communistic political party see fewer tourists than those who participate in a democracy. Also, some current political leaders may dissuade tourists from traveling abroad. President Erdogan of Turkey scares several European travelers who have frequently visited the Turkish Mediterranean beaches for holiday. Due to this political instability, costs to travel to Turkey have decreased to encourage a new group of tourists to visit Turkey. This new group of tourists is likely to be more price sensitive than they are sensitive to safety and security. Often tourists are told to stay away from political demonstrations as they are a hotspot for acts of terrorism and violence. Thus, it is proposed that:

P11: Stable political economies favorably influence destination competitiveness, whereas unstable political economies unfavorably influence destination competitiveness.

3.12 Resources

Resources are best defined as assets that can be transformed to produce a benefit. Many countries have a unique set of resources which work together to attract tourists to a certain destination. There are many types of resources, cultural/heritage resources, capital resources, human resources, natural resources and knowledge resources (Hong, 2009). High levels of these resources can positively affect TP. Unique sets of resources add value to a destination, making it more important for tourists to travel specifically to that destination. For example, if a tourist wants to go to the beach, there are thousands of destinations with ocean fronts. However, if a tourist wants to go to the beach and go to a bioluminescent bay, they only have three options in Jamaica, Vietnam and Puerto Rico. The bioluminescent bay, therefore, gives these destinations a competitive advantage, especially to Puerto Rico, which is home to three of the five bioluminescent bays. Thus, it is proposed that:

P12: High levels of resources, particularly unique ones favorably influence destination competitiveness.

4. TABC indicators of destination competitiveness

The TABC model created by Manrai and Manrai (1993) has three main components, namely, tourism attractions, tourism basics and tourism context. The TABC model provides for the effect of environmental factors discussed in the previous section on various components of the model. In doing so, many linkages are created to prove that these elements are vital as indicators/measures of DC.

4.1 Elements included in TA, TB, TC and TP

Each category of the TABC model has its subcategories. These subcategories can be influenced by multiple environmental factors. As we delve further into TAs, TB and TC, these relationships will become more apparent. Further, the three components of the TABC model together influence the TP of a destination.

4.1.1 Tourism attractions.

Tourists have evolved. Their expectations have changed, and in doing so, “isolated or previously unknown destinations have become places to be explored” (Cracolici and Nijkamp, 2009). Each destination offers different experiences, and the differentiation of TAs provides tourists with a multitude of experiences to choose from. “Tourists’ quest for experiencing different cultures, landscapes, and wilderness” (Ayikoru, 2015) has allowed even countries that are not fully developed to breach into the tourism sector. Today, tourists want the unique and authentic experiences one can obtain from visiting unique natural attractions with exceptional scenic beauty and of immersing themselves in unfamiliar cultures. The top five motivators for tourists are to relax, to enjoy good weather, to have fun, to forget day-to-day problems and to increase knowledge of new places (Kozak and Rimmington, 1999). These motivations of the consumer (tourist) guide the producer (destination developer and marketer) to offer benefits the tourists are looking for. Without the initial attraction of a destination’s mix of activities, tourists would not be persuaded to visit it.

TAs are, therefore, the core attractors to a certain destination. Many aspects make up TA. Different people are attracted to destinations for different reasons. What makes a destination competitive, is a unique combination of cultural and natural attractions. Resources are a huge cultural attraction. TA include natural wonders/scenery, flora and fauna, pristine nature, national parks and reserves and world heritage sites. Many tourists travel to experience another destination’s culture by visiting museums, going to cultural/historical districts and folk villages, taking in the art and architecture of the city and tasting the cuisine. Also, activities such as mountain sports, land sports and adventure/extreme sports attract adrenaline rush seekers. Other attractions include recreational facilities, fiestas and festivals, shopping, amusement and theme parks, entertainment and nightlife. Anything that initially attracts a tourist could be considered a tourist attraction.

Diving into these resources further, a direct relationship between these subcategories and TA exists. The literature strongly supports that TA are fundamental for DC. In the model created by Ritchie and Crouch (2010), core resources and attractors are the second tiers. “Regional tourist attractions” is also a category in the tourism attractiveness scheme created by Cracolici and Nijkamp (2009). Core resources and attractors are also an important factor in the tourism cluster development model (Kim and Wicks, 2010). The natural resources and geography of a destination provide an absolute advantage. The seven natural wonders of the world are the Aurora Borealis, the Harbor of Rio de Janeiro, the Grand Canyon, the Great Barrier Reef, Mount Everest, Paricutin and Victoria Falls. These natural wonders have comparative advantages unmatched by other natural wonders. This shows that “natural resources can be considered among the most important resources for tourism destinations” (Cucculelli and Goffi, 2016). Also unique to individual destinations are flora and fauna. Uganda, having a convergence of vegetation types, is often referred to as “Africa’s big botanical game” (Ayikoru, 2015). The author further points out that Ugandan tourism “mainly attracts those interested in the rare mountain gorillas and bird watching.”

Sustainability is required to maintain these natural resources. In addition to sustaining wildlife, destinations must also protect their nature. National parks and reserves maintain the pristine nature of many destinations as these parks are well regulated by government park authorities.

The UNESCO has established several world heritage sites which also act as a primary motivator for tourists. For example, Italy is a tourism leader and “has more UNESCO world heritage sites than any other country” (Cucculelli and Goffi, 2016). Italy also has thousands of museums and buildings portraying its art and architectural history. It is no wonder then that Italy is ranked as Number 5 based on DC score (Assaker et al., 2014).

Italy also has thousands of touristic sites, hundreds of medieval villages and historic churches and a great number of museums and archeological sites, which are spread all over the country. In a study about the importance of destination image of Italy done by Baloglu and Mangaloglu (2001), “historic, ancient ruins, archeology, old” were some of the most frequent responses about Italy.

In that same study, the responses that came even more frequently were, “food, cuisine, pasta, and wine” (Baloglu and Mangaloglu, 2001). This illustrates that not only is cuisine a necessity but the variations of ingredients can attract tourists. For example, in Southern Asian countries, a tourist could expect to find a variety of curries. In Japan, they would find a large variety of fish. In Austria, they would find Apple Strudel and Wiener schnitzel.

Depending on a tourist’s motivations for traveling, activities such as mountain sports and adventure sports, the Alps draw thousands of tourists each year for hiking, snowboarding and skiing, paragliding and skydiving. Switzerland has an especially large market for those looking to catch an adrenaline rush. The Alps, however, span multiple countries including, Germany, France, Austria, Italy and Spain. Along the coast, you will find more opportunities for water sports, such as windsurfing, surfing, kayaking and sailing. Hawaii and South Africa have some of the most popular surfing beaches, and many tourists travel there just to surf.

And finally, “events, leisure activities, nightlife, and shopping are primary motivations for visiting a destination” (Ritchie and Crouch, 2003). These activities can be found almost anywhere today. However, some events are unique to certain countries. For example, the running of the bulls in Spain or Oktoberfest in Munich, Germany, both events attract a very large number of tourists. Also, shopping centers such as outlets or popular shopping streets can attract tourists. It is especially true when the exchange rate is favorable for the tourists. The streets like Fifth Avenue in New York City, Bond Street in London, Ginza in Tokyo and the Champs Elysees in France all add tourism value to their respective destinations.

4.1.2 Tourism basics.

While many tourists want to experience new cultures, they do not want to “relinquish the familiar comforts and security of their home environment” (Ayikoru, 2015). TB, such as the restaurants and number of hotels, supports the initial attraction of destinations. Increased numbers of hotels, restaurants and tour operators can also sustain a larger number of tourists. For travelers, transportation services and facilities are vital and allow them to get to and from desired points of interest (Ritchie and Crouch, 2010). Bali has built the Benoa-Ngurai Rai-Nusa Dua toll road, extended their airport and renovated hotels to increase room capacity, all to support a larger number of tourists (Chin et al., 2015). While TA establish a motivation for travel, TB support that motivation.

The category of TB relates strongly to the physiography tier of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Under TB, the model has 20 subcategories. Each related to TB in its unique way. The number of airports and seaports are vital for accessibility. A destination that is not accessible cannot have a competitive advantage. Miles of roadways, railways and waterways are key to conveying tourists from different points of interest. For local transportation systems to be effective and a destination to be accessible, these basic infrastructure elements must be in place.

Other essential attributes for tourism destinations include accommodations, food, guide services and transportation (Hong, 2009). Acquiring shelter and food is a basic need, and by having an adequate selection of accommodations and restaurants, destinations gives tourists more choices. Providing tourists with enough information through tour operators and tourist information centers is also important. Having plenty of tour operators, who offer guided tours of several scenic and cultural destinations, is a way to allow tourists to “sit back and take it all in”.

Additionally, having tourist information centers can help make tourists aware of the several activities available for tourists. Local transportation systems play a critical role in the accessibility of a destination and therefore provides an important competitive advantage (Hong, 2009). The availability of efficient public and local transportation, allows tourists to get around much easier about the points of interest of a destination. Therefore, local transportation is expected to offer a schedule convenient for tourism (Hong, 2009). This gives tourists more flexibility when traveling to unfamiliar places. In addition to local and public transportation, the number of airlines, domestic and international, is important for tourists who must fly to get to the destination. Many large, developed countries, such as Germany, have many domestic airlines. Air Berlin, Condor and Germanwings are just a few of their domestic airlines. Lufthansa is their most popular international airline and is part of the Star Alliance.

Basics such as hospitals and pharmacies are important to those traveling with disabilities. Hospital and pharmacies offer tourists security in knowing that they can be taken care of if something happens. Also, sanitation is a basic requirement that the tourists look for. Assaker et al. (2014) included sanitation as an infrastructure indicator for their DC model.

Finally, many tourists are used to luxuries like wireless internet and personal banking. Wireless internet allows tourists to check their e-mails and make international phone calls. Some developing countries are not technologically able to provide its tourists with these luxuries. In the emerging incentive, travel destinations model created by Xiang and Formica (2007), internet and wireless technology are associated with access to the business. For tourists to feel connected to home, internet access and international calling are vital. Going along with technology, having a reliable power supply is also important for tourists so that they can charge their devices and remain in the same comfort level as they do at home. Personal banking allows tourists to withdraw the currency of the destination. Having a variety of banks and an adequate number of ATMs would be important for tourists who do not have the currency of the destination.

4.1.3 Tourism context.

DC has become an increasingly popular topic for many developing countries, as tourism also affects the national economy. Crouch and Ritchie (1999) discuss that the implementation of “successful tourism development programs will likely impact the quality of life for residents.” Increased amounts of tourists will indirectly increase the amount of FDIs and Joint Ventures and directly increase tourist expenditures. This will create employment opportunities and improve infrastructure, not only improve conditions for tourists but residents as well. Whereas TA and TB motivate tourists to travel, the most powerful influence concerns safety and security (Ritchie and Crouch, 2010). Dwyer et al. (2014) conclude that “after the breakup of Yugoslavia, political instability, economic sanctions, and the NATO bombing in the 1990s” has lead Serbia to experience “a sharp decline in its tourism flows.”

TC comprises factors that could make a tourist wary of traveling to certain destinations. For example, a country with a high crime index would likely not attract many tourists out of fear. Going along with that, having a high tourism risk and national disaster index can also dissuade tourists from visiting certain destinations. Ritchie and Crouch (1999) identified terrorist events and environmental catastrophes as events which would dissuade tourists from visiting. This again relates to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, which postulates that security is a vital need. Another deterrent for tourists is a disease. Malaria has been identified as a health risk that lowers tourism (Naude and Saayman, 2005; Gallup and Sachs, 2000). Those countries that have huge outbreaks of a disease also have a lowered life expectancy. In the regression analysis done by Naude and Saayman (2005), life expectancy was identified as a key dependent variable. Other constraints to DC are Pollution Index and Quality of Life index. Assaf and Josiassen (2011) identified CO2 emissions in the environment as one of “the five most important negative factors.” Quality of Life has a parallel relationship with TP. The more competitive a destination is, the higher the quality of life for residents will be. This is due to the amount of foreign direct investments that come with high tourism numbers. Cucculelli and Goffi (2016) suggest “that the competitive destination is the one that increases well-being for its residents in the long term.”

Finally, the ease of doing business and the friendliness of people are also important factors of TC. Reichel and Haber (2005) identified “success in generating profit in times of geopolitical crisis” as a variable to measure DC. Assaf and Josiassen (2011) identified both “time required to start a business” and “service-mindedness of population toward foreign visitors” as a variable in their bootstrap regression. These factors all affect inflow of tourists, and if tourists are worried about their safety in a destination, TA and TB will mean very little to them.

4.1.4 Tourism performance.

Measuring relative performance of destinations is done by comparing, the number of international and domestic tourists, the amount of expenditures by domestic and international tourists, and the number of hotel nights. Assaker et al. (2014) identified international tourist arrivals and international tourism receipts as variables for their DC model and used tourist arrivals and receipts to measure TP. In research done by Cucculelli and Goffi (2016), the average length of stay was a determining factor of TP. These numbers, when compared with other countries, can determine a countries relative competitiveness. When Assaker et al., 2014, ranked countries based on their aggregate DC score, they took into account variables such as economy, infrastructure, and environment. The tourism indicators they used were international tourist arrivals and international tourist receipts. The top five countries, based on these findings, were the USA, France, China, Spain and Italy.

TP indicators are key to determining the gain or loss of tourists. The terrorist bombings in Bali caused “international tourist arrivals to decline sharply and hotel occupancy fell from 70 per cent to below 20 per cent” (Chin et al., 2015). Additionally, these numbers allow us to see just how important tourism is to certain destinations and their impact of GDP. Measuring TP is vital to determine how competitive a destination is.

4.2 Effects of environmental variables on TA, TB and TC

The environmental variables affect TA, TB and TC. As a result, these variables also affect TP. Most often resources, culture, demographics, geography and history affect TA. Countries with abundant natural resources have a comparative advantage (Hong, 2009). Countries that have a rich culture and history also have a comparative advantage, and therefore, the preservation of culture and history is also important. Geography determines the flora and fauna and natural wonders and scenery. Those destinations with unique geographical elements are likely to attract more tourists.

TB is most likely to be influenced by infrastructure, technology and opponents (competitors). Infrastructure investments in a destination are the most important functional bases (Hong, 2009). They support accommodations, transportation systems, accessibility and ethnic food. Having the technology to keep up with tourists’ normal activities is also important as tourists do not want to give up their daily luxuries. Competition in the hotel industry and gastronomy industry is also valuable. Increased competition brings more players, which means more variety and better quality.

Finally, society, politics, law and economy play an important part in a TC. The friendliness of society can influence a tourist to visit one destination over others. On the other hand, political instability can deter tourists from traveling to certain destinations. Going along with that, the legal system and types of laws a country has dissuade tourists from visiting those areas. The economy can also play a substantial role in determining where a tourist goes. A stable, growing economy will attract more tourists, and a growing global economy will allow more people to travel. Many of these variables affect more than just TC and could potentially affect all three categories of the TABC model. As presented here, the most common links between environmental factors and TABC categories were shown.

In Section 3, 12 propositions were developed depicting the effects of 12 environmental variables on DC. Our conceptual model portrays TA, TB and TC as indicators of DC, and in the model, these indicators are nested within DC. Thus, the 12 propositions also capture the effect of 12 environmental variables on TA, TB and TC.

4.3 Effects of TA, TB and TC on TP

As noted earlier, Italy is abundant with cultural attractors, such as world heritage sites and cuisine. It’s TP, as measured by the number of international tourist arrivals and amount of international tourist receipts puts Italy ranked as number five (Cucculelli and Goffi, 2016). This shows a positive relationship between cultural attractors and TP. Italy also ranks second worldwide in accommodation capacity (Cucculelli and Goffi, 2016). This figure relates to the number of hotels, a subcategory of TB, as an indicator of TP. Therefore, the relationship between TB and TP is positive. As stated by Ayikoru (2015), the various civil wars that took place in Uganda between 1970 and 2005, “have not only stifled progress but crucially, they have also defined and constructed the infamous negative image associated with Uganda”. The total foreign direct investments in Uganda fell almost US$1m between the year 2001 and 2002 (Ayikoru (2015). This demonstrates the negative relationship between TC and TP in case of Uganda. Overall, TP directly relates to a destination’s competitive position. Thus, it is proposed that:

P13:DC has a direct (either a positive or negative) effect on tourism performance.

5. Conceptual model

A conceptual model of DC summarizing the above discussion is presented in Figure 1. This model includes the environmental elements affecting, TA, TB and TC (TABC), and the subcategories of variables included in TABC. Further, the effect of TABC on TP is also captured in the model.

Two unique features of this model are:

the inclusion of a comprehensive list of environmental factors as determinants of DC; and

the itroduction of the TABC model as indicators of DC.

First, while the environmental factors have been recognized in existing research, their coverage is rather limited and fragmented. To the best of knowledge, comprehensive coverage of a large number of environmental influences (12 in the present study) has not been done so far. Furthermore, we discuss specific effects of these 12 environmental factors on the three components of DC and develop 12 propositions. The second unique characteristic of our proposed conceptual model is the TABC model, which is nested within the DC model and serves as indicators of DC. Again, while there are existing models of DC, TABC model is relatively simple and is rooted in Maslow’s need hierarchy theory. Thus, it also better captures tourists’ needs, wants and motivations for tourism and the attributes/benefits they seek in a destination, that is, the demand side of the tourism market. These attributes/benefits, in turn, provide a better measure of DC and are a better predictor of the effects of DC on performance, which in our model is measured by some variables/dimensions. The effect of DC on TP or TA, TB, TC together on TP is captured in P13.

Overall, we feel that our model of DC incorporating environmental determinants and TABC (Attractions-Basics-Context) indicators (the demand side perspective of the market) is comprehensive yet simple and grounded in a classical theory like the Maslow’s need hierarchy compared to other models of DC.

6. Findings and managerial implications

Destination management is an important theory but should not be included in the first step of determining DC, as it ignores the demand-side perspective of the tourism market. Tourism, like most industries, is constantly changing, and therefore, destinations must also adapt their marketing techniques. It is for this reason that destination management is not a good starting point. DMOs must first assess all aspects of what makes a destination competitive. The DMOs can then improve destinations’ weaknesses and promote their strengths. This is because tourism is considered as a luxury good as suggested by Kara et al. (2003).

Tourism is a luxury good. Marketers and DMOs must realize that when trying to persuade tourists to visit certain destinations rather than others, they need to establish and demonstrate their destination’s competitive advantages. The model introduced by Manrai and Manrai (1993) allows these organizations to determine what makes one destination unique compared to others.

Once a destination’s competitive advantages have been determined, the same can then be marketed to the relevant tourist segments. There are many different tourist segments today, and different features of a destination must be promoted to attract different types of tourists. Social media and internet blogs have become successful marketing mediums (Lin and Huang, 2006). Additionally, “past travel experiences encourage people to engage in online information, sharing with complete strangers” which can increase a country’s competitive position (Martin et al., 2015).

The conceptual model presented by Manrai and Manrai (1993) is an important guideline in determining a destination’s competitive position.

An analysis of the literature review in Section 2 of this paper and summarized in Table 1 (1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 1.4, 1.5 and 1.6) indicates the dominance of “production (supply-side perspective) orientation” over the “marketing (demand-side perspective) orientation.” Efforts to build DC have resorted to issues such as destination management. Instead, the starting point should be a customer (tourist), need assessment and development of marketing orientation. However, a majority of the research studies on DC lack this orientation. From this standpoint, the current research also makes contributions to the advancement of theory on the subject of DC

7. Directions for future research

One possible area for future research is to determine the unique combinations of TA, TB and TC that draws certain types of tourists. Research on the different segments of tourists also provides ample opportunities for designing an appropriate marketing mix. Also, there is currently a positive relationship between TB and TP; however, once a location gets exploited for its tourism purposes, it often loses the local culture that the residents bring. As we continue to study tourists’ behaviors, motivations for traveling may change as well, and destinations should be ready and willing to adapt to those changes but not so much that they lose their uniqueness.

A related area if future research opportunity is to examine the relative impact TA, TB and TC (and the specific elements included in these three components) have on tourism performance. Examining these two research topics in different environmental settings opens up numerous opportunities for conceptual as well as empirical research.