1. Introduction

The improvement of the quality of life of the least favoured communities has been particularly investigated in the last 20 years (Lashitew et al., 2022). In 1999, an academic debate was initiated at the Digital Dividends Conference (Prahalad and Hammond, 2002a) on the inclusion of the poorest as “consumers” within the value chain. This initiative was led by C.K. Prahalad (Prahalad and Hammond, 2002b) under the construct of creative approaches to transform poverty into opportunity. This initiative aimed company executives, politicians, non-lucrative company directors and other interest groups to see poverty as an issue with attainable solutions (Pitta et al., 2008).

Authors such as Karnani (2007) and London and Hart (2004) supported this view that helping the poorest is the responsibility of the private sector. They also criticised “inclusion” because in practice, it proves to be a good opportunity for multinationals to penetrate new markets and not as a strategy to relieve poverty at the bottom of the pyramid (BoP) (London et al., 2010).

The strategy behind BoP, has been used to understand and analyse the role of the poor in the supply chains of the various sectors (Zomorrodi et al., 2019), as well as their linkage with other social concepts, such as social entrepreneurship (Acosta Veliz et al., 2018 ), the creation of shared value (SV) (Dembek et al., 2019) and innovation.

The BoP initiatives differ from traditional business initiatives since they take into account the position of the poor in the value chain, both as consumers and entrepreneurs (Karnani, 2009). Thus, the creation of SV is associated with the development of businesses and the mitigation of poverty (London et al., 2010).

The literature review of the concept of SV shows that its origin remains unclear (Maestre Matos et al., 2020), given the various scholars that claim authorship. However, there is a consensus on its linkage with the creation of a simultaneous economic and social value for the development of various business models, including BoP businesses.

The essential pragmatic and academic challenge of the concepts is to simultaneously create social and financial value when there is also interaction with uncontrolled external conditions (Kolk et al., 2014). The so-called BoP 1.0 approach of market potential as an economic segment (Karnani, 2007) becomes BoP 2.0 when economic realities and collaboration create capacities in poor regions (Dembek et al., 2019; Hart et al., 2016). The BoP 3.0 includes a proactive version of the business oriented to open innovation with collaborative ecosystems (Caneque and Hart, 2017).

The creation of business value is impacted by the institutional values (Williams and Vorley, 2015) that may increase or restrict their development according to the behaviour of individuals (North, 1991); and therefore, it is essential to identify the institutional factors (formal: provides “official” structure and informal: shared rules, usually unwritten) that are immersed in the BoP culture and help create SV among its members.

The BoP implies - in the case of emerging countries - to do business with small growers, considered the poorest in rural areas. This research focuses on informal institutions of small banana growers and the resulting creation of economic and social values. For Colombia, growers show financial poverty indicators reaching 38.6% and extreme poverty reaching 18.1%. This compared with population from urban areas (24.9 and 8.5%, respectively) (DANE, 2019). But poverty must be seen in economic and social perspectives and share value could support this endeavour. Thus, the research question is which are the informal institutions that support the creation of share value in BoP agri-businesses?

The case of study to answer this question uses small banana growers (BoP) in the Magdalena (northern region of Colombia). They represent 6.9% of the exported bananas in the region and the industry employs approximately 640 families (ASBAMA, 2017). They had to conform cooperatives to strength its bargain power in the whole value chain: backwards with suppliers of raw materials and forwards mainly with international trading companies (Maestre Matos et al., 2019). Additionally, the support of guilds (such as ASBAMA and AUGURA) and scientific institutions (e.g. research-institutions) at the region allows the composition of a cluster's type of organisation including both alliances and networks (Lombana, 2006) Finally, the innovation in process and marketing (e.g. organic and fair trade) are two of the competitive advantage developed by small growers (Forero-Madero et al., 2006; Garavito Hernández and Rueda Galvis, 2021). Thus, the configuration of share value as declared by Porter and Kramer (2011, 2006) are clearly identified in this case of study, since the quality of life and income of producers in this region have improved (Maestre Matos et al., 2019). However, the concept of SV is not free of criticism as shown in the literature review in the following section. Thus, the banana growers’ case becomes important to recognise the social benefits of share value and not only as economic strategy. Therefore, this paper’s objective is to analyse informal institutional factors that help create SV in BoP farm businesses, taking as a theoretical basis the new institutional economic theory and definitions explained by North's (1991) framework.

This research uses a mixed research design, as shown in section 3. This enabled us to test the hypotheses based on the literature review using a quantitative analysis of the structural equation modelling. Finally, qualitative analysis of the information validates previous outcomes.

2. Literature review

In recent agribusiness literature related with the BoP, there is also an emphasis to the circular economy as a “model of production” and consumption, which involves sharing, leasing, reusing, repairing, refurbishing and recycling existing materials and products as long as possible. In this way, the life cycle of products is extended (European Parliament, 2015). Insofar, it holds all members of the chain responsible for making reasonable use of resources and using clean production models (Hamam et al., 2021). This is much in line with how the agricultural sector creates value, understanding that its methods, although it satisfies basic human needs, within the value-chain is not necessarily sustainable in the short term, and it must be changed to the long term (Sadovska et al., 2020). Moreover, as highlighted by German et al. (2020), issues such as land ownership and integration of local labour into global value chains do not necessarily have the degree of inclusion that is pursued by the BoP. In fact, the cases mentioned by the authors conclude that the pressure from governments to remove subsidies to small growers and the raising standards (with cost implications for producers), increase the exclusion gap. Frimpong-Boamah and Sumberg (2019) add that political value (e.g. due to historical employment history) can prevail over economic value and perpetuate highly inefficient industries. The positive perspective of value creation continues, by replacing philanthropy with stimuli to productive capacities, productive reconversion (Wiśniewska-Paluszak and Paluszak, 2019), creation of clusters, transparency, collaborative work in planning, market intelligence and knowledge (Diamond et al., 2014).

The theoretical basis for this research is the concept of SV and the debate on its origin. This part includes a review of how informal institutions affect the creation of SV in bottom-of-the-pyramid business models.

2.1 Shared value (SV)

There is a debate of the origin of the SV concept: (1) Porter and Kramer (2002) as their first representatives; (2) it was as implicit concept in the application of the stakeholders theory (Strand et al., 2015) and (3) in the corporate social responsibility (CSR) company strategy (Crane et al., 2014). To understand this debate, some concepts issued by these scholars are shown.

Porter and Krammer (2002) were the first to mention that the economic and social objectives could be integrated into and form the company's corporate strategy known as SV. Although the same authors criticised the way in which organisations had implemented CSR, it has been concluded that the concept of SV proposed by Porter and Kramer (2011 is the most popular of all theories. With regards to the stakeholder theory, some authors state that the achievement of the main purpose of creating value for all the stakeholders is the actual definition of SV (Strand et al., 2015). And, finally, the CSR defenders mention that the new trend for this strategy is to incorporate the economic and social values into the company processes (Ezzi and Jarboui, 2016; Zadek, 2005).

Among critics of the concept of SV and the new “great idea” of Porter and Kramer (2011), Crane et al. (2014) stated that the concept created by them was not very original and does not take into account any previous academic discussions.

Despite the differences on the issue of the origin, scholars provide some similar characteristics to the concept and define SV as the business integration of a created economic and social value (society and environment) by an organisation, thus generating positive impacts for all the stakeholders. In this sense, managers are expected to align their strategies in order to implement plans that provide a solution to the issues and interests of all the stakeholders (Mühlbacher and Böbel, 2019).

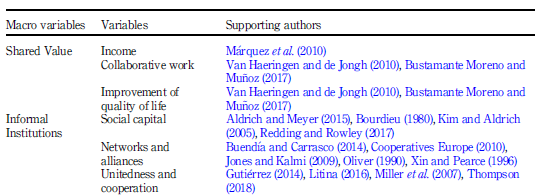

For the case of BoP businesses, the creation of an economic value can be measured by the income generated in the course of development of the business (Marquez et al., 2010), whereas the creation of a social value can be established by looking at the cooperative work being developed amongst members of the BoP and the improvement of their quality of life (Bustamante Moreno and Muñoz, 2017; Van Haeringen and de Jongh, 2010).

North (1991) states that the institutions are rules, acceptance procedures and moral and ethical behavioural standards, designed to restrict the behaviour of individuals. He classifies institutions between formal and informal. This research focuses on informal, namely, habits, traditions, sanctions, taboos, and codes of ethic, which restrict or improve the behaviour of a community. For these research informal institutions identified in BoP business models as creators of SV are social capital, networks and alliances, and cooperation.

2.2 Social capital

Bourdieu (1980) is recognised as a main representative of the social capital concept at the institutional perspective. He defines social capital as the sum of the resources, actual or virtual, that are associated to belonging to a group. This set of agents are not only provided with common characteristics but also permanently and strongly linked.

According to Kim and Aldrich (2005), social capital could be defined as the resources available to people through their social connections, considering them as resources of equal or more importance than having sufficient financial funds (Dong, 2019) to set up a business.

Various authors study the linkage between cooperation within communities and social capital (Fukuyama, 2001), proving that the greater the social cohesion in a community, the more developed the social capital. Thus, there is an improvement of economic and community development (Redding Rowley, 2017).

In the same way, cooperatives see themselves strongly linked with social capital, as these types of businesses rely on informal long-term agreements rather than formal short-term contracts (Lui et al., 2009) Trust and the cooperation principle generated by the social capital of the cooperative members and the network integration are of major importance. Cooperatives represent a meso-level indicator of relational capital that can complement micro-level measures, which are generally assessed at an individual level (Bruni et al., 2019).

In line with Gutiérrez (2014), growers’ cooperatives are an instrument for the rural development of small producers. They represent an opportunity to become part of an organisation with economic advantages on account of team working and their horizontal or vertical integration.

Thanks to the development of such relationships, small producers have been able to overcome their difficulties and improve their quality of life (Gutiérrez, 2005).

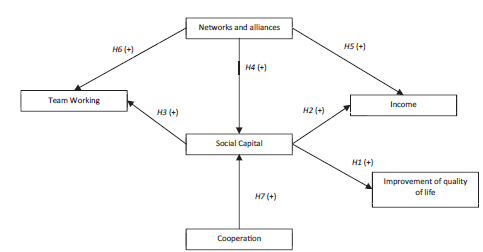

H1. Social capital is positively associated with the improvement of quality of life.

H2. Social capital is positively associated with income.

H3. Social capital is positively associated with team working.

2.3 Networks and alliances

Networks refer to the personal and organisational connections used for the operation of a business (Xin and Pearce, 1996) as a competitive strategy (Oliver, 1990). Specifically in small businesses, researchers relate networks with obtaining information on the business environment (Kingsley and Malecki, 2004); whereas, in transition economies, networks help to obtain the resources, taking into account the strong political manipulation existing in such markets (Davies et al., 1995).

Networks can provide opportunities or create restrictions in the organisation's performance (Kilduff and Brass, 2010; Restrepo-Morales et al., 2019).They use connections and trust to optimise performance, reduce costs of information sourcing (Seghers et al., 2012) and identify new opportunities (Stuart and Sorenson, 2007).

Social networks are as important in cooperatives as in capitalist companies, as they both have organisational, financial and knowledge requirements. Studies of European cooperatives have proven the existence of its greater penetration when the group is in the same country (Cooperatives Europe, 2010).

On the other hand, in poor environments, networks are the most important capital available (Bauer et al., 2012) and cooperatives become relevant (Buendía and Carrasco, 2014).They are a way of reorganising the activities and the market (Malo and Tremblay, 2004) for sectors with low income that teamwork in the search of their own objectives.

H4.Networks and alliances are positively associated with social capital.

H5.Networks and alliances are positively associated with income.

H6. Networks and alliances are positively associated with team working.

2.4 Cooperative principles: cooperation

Cooperative associations are an alternative way of organisation with defined characteristics and established principles (Zabala, 2007), including cooperation. The former refers not only to the way the members relate with the cooperatives (voluntarily and openly with the purpose of developing common objectives) (ACI, 1995), but also to the cohesion of the members to generate economic and social values (Gutiérrez, 2014), in other words, SV.

Cooperation refers to collaboration through local, national, regional and international structures in order to serve their members more efficiently and strengthen the cooperative movement.

A more exhaustive review of this topic proved that cooperation is closely related with social capital development (Thompson, 2018). For example, research into communities with low social capital proved that cooperation and the will to share common goods decreases as the social capital decreases (Becchetti et al., 2015). In the same way, research into the farming sector proved that the lower the land production, the more the cooperation; and in turn, the more the cooperation, the higher the development of social capital (Litina, 2016).

On the other hand, cooperation has been proven to rely on the relationships among members of the group (networks and alliances) (Miller et al., 2007) and that the better the relationships, the safer is to develop joint projects (Koh and Rowlinson, 2012).

H7. There is a positive relationship between cooperation and social capital.

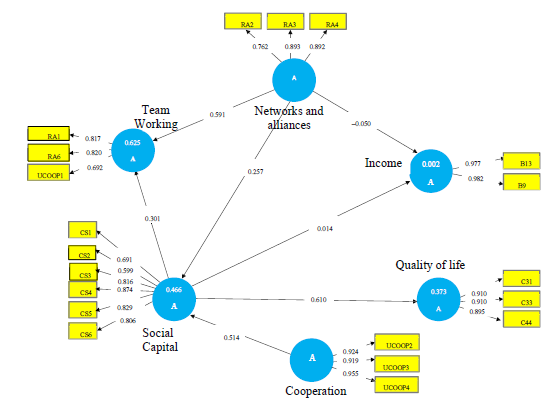

Figure 1 shows the theoretical model for the linkage amongst the various informal institutions. Team working and improvement of the quality of life are the variables to measure social value, while income is the measure for the generation of economic value.

Social capital, networking and alliances are informal institutional factors that help to generate SV, which is measured through economic value (in the model through income) and social value (quality of life and team working). Therefore, this research will determine whether these informal institutions (social capital, networking and alliances) help create SV in BoP farm businesses.

3. Method

3.1 Data collection

This research employs the case study method with a mixed research design, using qualitative and quantitative data.

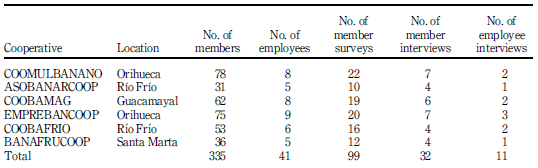

The case study includes 6 banana cooperatives (see Table 1) situated in the northern area of Colombia (Magdalena region) making a simple and holistic case study according to Yin's (1989) classification. Following Eisenhardt (1989), who established the analysis of 4 case studies as a minimum requirement in order to create a theory, this research analysed 100% of the cases existing in the area (6 cases). As shown in Table 1, the cooperatives are 335 small growers and 41 employees.

The internal validity of the case study method was checked using Patton's (1987) information triangulation process. (1) Triangulation of the sources (comparison of data from the interviews with the various actors of the cooperatives: managing directors, other directors without management roles, and employees, management reports and records). (2) Triangulation of the information by data collection techniques (application of various techniques for the collection of data such as direct observation, interviews, surveys) (1). (3) Pattern adjustments (constant comparison against the findings from the literature review). The external validity of the case study was provided by the number of cases under analysis in this research (6 cooperatives) which allowed the construction of theoretical generalities, given the aforementioned requirements proposed by Eisenhardt (1989).

The reliability of the case study method is established by the possibility of replicating the research under the same terms/protocols obtaining similar results. For this research, the analysis of 6 cases allowed for replication of the cases under analysis. The results obtained by the first case repeated with the analysis of the subsequent cases.

The protocol designed for the case study of this research followed the deductive logic, taking Yin (1989) and Eisenhardt (1989) as a reference: (1) Raising a research question; (2) Establishing theoretical propositions; (3) Defining the unit of analysis; (4) Data collection; (5) Data analysis with the hypotheses raised quantitative analysis through the structural equation modelling technique, specifically the partial least squares (PLS) technique and the qualitative analysis of the interviews with the use of the Atlas.ti. V7 software. (6) Interpretation of the results and (7) Sharing the results with the parties involved in the study.

The information collection process was performed in the banana area of the Magdalena region (Colombia) with visits to lands and the cooperatives during the 2015-2017 period. For the collection process, 99 perception surveys were carried out with small producers using a structured questionnaire which is presented in Appendix 1. The questionnaire included questions relating to the informal institutional factors affecting the development of team working, improvement of the quality of life and income, according to the variables defined in the literature review (see Table 2). The assessment of the answers to the questions designed in the questionnaire was presented in the form of a Likert scale. The questionnaire was validated by experts in bottom-of-the-pyramid businesses and experts in the new institutional theory. The number of respondents was established through the finite population formula (Martínez Bencardino, 2012). The value of p and q were determined by the variance of the data performed during a previous research study dealing with the characterisation of small producers (Maestre- Matos et al., 2019). That study concluded that the object of study showed homogeneity in its characteristics: low level of training, exporting bananas with international certification and association between small-producers' cooperatives and trading companies.

On the other hand, 32 in-depth interviews were carried out with small growers (6 with managing directors and 26 with directors without managing roles) and with 11 cooperative employees for (see Table 1). The interview was of 1.5 h long in average, using a semi-structured questionnaire which is included in Appendix 2. It contained questions related to the operation of the cooperative and its influence on the informal institutional factors: income, improvement of the quality of life and development of the team working. The semi-structured questionnaire was validated by experts in the field. The number of interviews was determined by theoretical sample saturation, this is, when the interviews began to show repeated information.

It is worth highlighting that both data collection processes followed simple stratified sampling to guarantee the participation of all the cooperatives.

3.2 Analytical procedure

Considering the mixed design employed in the research, a first stage of the quantitative analysis used the partial least square technique of the structural equation statistical method, which helped to test the hypothesis proposed and derived from the literature review. These results were compared using a qualitative analysis of the interviews and direct observation with the triangulation of the research findings.

3.3 Quantitative analytical procedure

Partial least square technique of the structural equation statistical method. This type of structural equation modelling is carried out by identifying the relationships between variables indirectly measured (Hair et al., 1998). The use of latent or unobserved variables (see Table 2, variables column) represent theoretical concepts and manifest indicators or variables which derive from measurements (see Table 2, survey code), which are used as information for statistical analysis (Williams et al., 2009). The PLS method is known as flexible modelling (Wold, 1980) because it does not make assumptions for the indicators such as size, data distribution and measure levels.

For the purposes of this research the latent variable indicates the perception of the small producers for each of the informal institutional factors under study.

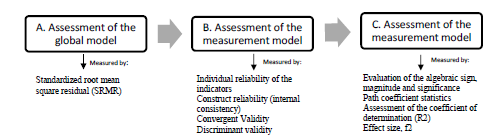

The development of structural equations, the first stage was the definition of endogenous and exogenous constructs based on the literature review and the hypothesis from the previous section. This allows the design of the model including the indicators and their correlations with the constructs. The second stage was established by the assessment of the model and its results, as Figure 2 explains. The results and analysis of each of the assessments are presented in the next section.

Following the analytical quantitative process, as seen in the methodological section, Figure 3 shows the structural equation modelling of the informal institutions, which includes the assessment of the model in Figure 2.

Assessment of the global model: this assessment uses the goodness of fit index provided by the standardised root mean square residual (SRMR) (Hu and Bentler, 1998). It measures the difference between the correlation matrix identified and the correlation matrix of the model. The lower the SRMR, the better the model adjustment. The model used in this research obtained a SRMR of 0.101, thus complying with the proposals of Ringle et al. (2009) who stated that a SRMR <0,10 could be a valid adjustment value.

Assessment of the measurement model: Henseler (2017a, 2017b) proposes the same indexes used for the global model but applying them to the saturated model. According to Hu and Bentler (1998), the SRMR must be < 0.08 if the model is to be properly adjusted. The model analysed for the saturated model yielded a value of 0.789, thus the conclusion is that the measurement models are accurate, and the information provided by the indicators explains the model.

The loadings (λ) or simple correlations between the indicators and their respective constructs range between 0.762 and 0.982, with the removal of the indicators that do not comply with the criteria established by Carmines and Zeller (1979), who indicate λ ≥ 0.707 as reliable and that indicators with very low loadings (λ ≤ 0.4) should be removed (Hair et al., 2011).

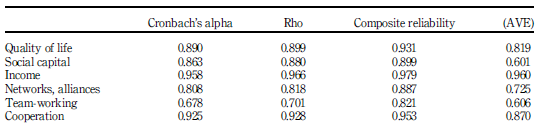

An assessment of Cronbach's alpha, composite reliability (ρc) (Werts et al., 1974) and rho: Dijkstra-Henseler's (ρA) (2015) show that all variables comply with the parameters established by Nunnally (1994). The author suggests a value of 0.7 as an adequate level for “modest” reliability at the early stages of research; therefore, as Table 3 shows, the model is reliable in terms of its construct.

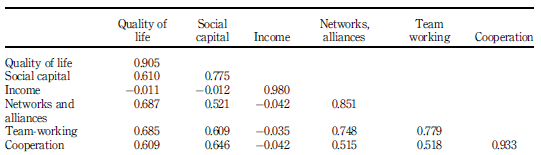

The average variance extracted (AVE) from the variables offers values that are ≥ 0.50 (Fornell and Larcker, 1981), which explains that a set of indicators represents at least 50% of the variance of the allocated indicators, with this proving the convergent validity of the model (Table 3). And lastly, all the measures comply with the discriminant validity criteria assessed by the HTMT (Henseler et al., 2015) (see the values in diagonal of Table 4).

Assessment of the structural model: As seen in Figure 3, all the path coefficients (numbers situated between the arrows associating the latent variables) can have magnitudes between +1 and −1.

3.4 Qualitative analytical procedure

Each interview was transcribed in text format. An adaptation of the secondary information was also prepared in a format that is compatible for use with the qualitative research software for specific data, Atlas.ti v 7.0. This tool helped establish quotations and categories that enabled us to compare the results obtained through quantitative analysis.

The qualitative information analysis process follows Strauss and Corbin (1990), which consisted in the definition of keywords of the variables defined in the SEM model. According to the Atlas.ti software, the so-called “codes” are resulting from interviews’ analysis, generating the citations that support the findings established in the quantitative model.

4. Results

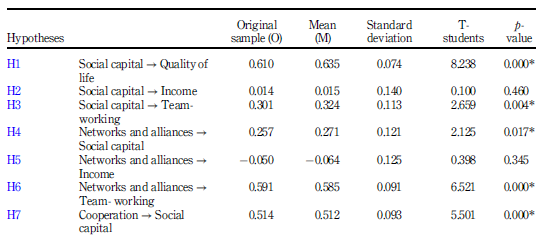

Both structural equations and interviews confirm the creation of social capital among small producers and their strong linkages, as well as their brotherly and fraternal relationships: “We are like a family, and we all support each other” as argued by a small grower from a cooperative”. Thus, there is a positive linkage between social capital and team working, supporting H1 and H3 (See Table 5). The interviews supported that through the development of such relationships small producers have been able to confront difficulties and improve their quality of life. On this regard, a manager of a cooperative said “with the cooperative's support, we improved the quality of life of growers. For example, with their houses, their farms, their production one can see if they are fine or not”.

The structural equation modelling confirms the linkages between networks and alliances with team working and also with social capital, thus H4 and H6 are not discarded (See Table 5). This is also confirmed by the interviews to small growers “when one of the producers requires a tool and another has it, it is lent to him; because we all must comply with everything and we all collaborate. We cannot let them uncertify us”. Small growers believe in their inclusion as a network in an established banana value chain. This chain has strong linkages among small producers, cooperatives and trading companies as confirmed by a manager of a cooperative “the relationship between audit and traders is strong, between growers and traders is strong and between growers and managers is strong”. Thus, due to the work carried out by the trading company, small producers could reach international markets.

Table 5 Assessment of the informal institutions hypothesis

Note(s): * Indicate that the coefficient is significant 1%

Source(s): Own, extracted from the data

This research identified cooperation as a fundamental value of the cooperatives regarding the creation of social capital, which proves H7 (see Table 5) and results in better quality of life for small growers. As they have commented: “We share between us machinery, equipment, employees and knowledge of how to do things” and “we are a family of banana producers who, when being together have had to learn from each other, work as a team, not as competition, but as people who are working for the same purpose”.

During the qualitative analysis one of the growers said: “Cooperatives have helped us to grow, to be better and to have unity” in order to grow and develop. It is fundamental for them to help each other and use their actions to move away from the stigmatised belief that cooperatives always seek individual benefits. This is confirmed by the manager of a cooperative, “It is difficult to remove the stigma that associations or cooperatives are synonymous with stealing, or making profit individually. We are a mean of mutual aid among producers for the economic and social growth of all”.

At the end of the research one of the most significant findings was associated with income generation and the identified institutional factors. The structural equation modelling showed that the existing linkage between informal factors and income is not significant (e.g. social capital does not have a major impact on income, thus H2 is discarded - see Table 5), and the producers confirmed in their interviews the results of the mathematical model: “income depends on the number of boxes produced and the same number of boxes is not produced every month. That varies a lot depending on the environmental conditions”, they also mentioned “sales also depend on the farm's production which in turn depend on the temperature, water, fertilizers, and nutrients in the soil. The same production is not always generated”.

Finally, taking into account the negative sign of the H5 coefficient, no explanation was available for the linkage between networks and alliances and income (See Table 5).

In the above model, the R2 values for social capital, quality of life, income and team working were 0.466, 0.373, 0.002 and 0.625, respectively (see Figure 2). The predictive capacity of these two models is, in general terms, moderate and substantial, with the “income” variable not being explained by the informal institutional factors.

On assessing the effects between the variables of the model and the informal factors and following Cohen (1988), networks and alliances were found to have major impact on the generation of team working (0.678), while social capital impacted on quality of life (0.594). This is ratified both by the producers, with statements such as “among the small producers we support each other a lot, if a partner is down with the delivery, the other can support it”; and by the cooperative's managers who stated that “with the joint support of all the members of the cooperative, the living conditions of the producers have been improved”. Finally, cooperation impacted on social capital (0.364), reflected in sentences such as “we know each other and we support each other ” which are expressed by small producers to confirm these findings. All these linkages help to create social value for the small producers. In the same way, a small impact was identified between network and alliances, and social capital (0.091) and between social capital and team working (0.176). With regards to the creation of economic value, no impact was established between the variables associated with the income. Therefore, this research was not capable of proving an increase in the sales of small producers on account of the influence of informal institutional factors.

5. Discussion

When comparing the research results with other studies, it was found that the linkage between social capital and the BoP strategies is coherent, as suggested by Gutiérrez (2005) and Dong (2019). Moreover, the banana cooperatives of the Magdalena region were the social organisational level and the space where small farm producers generated social capital, as argued by Gutiérrez (2014).

This study allowed to corroborate what was stated by different authors such as Bauer et al. (2012), Jones and Kalmi (2009) and Valentinov (2004), who pointed out that networks are the most important capital in poverty environments, while cooperatives are the means for the execution of identified opportunities (Kilduff and Brass, 2010) and for the reorganisation of market activities (Malo and Tremblay, 2004). In the same way, this study confirms the positive linkage between cooperation and development of social capital as indicated by Thompson (2018) and Becchetti et al. (2015). Moreover, through the construction of social capital, it is possible to share knowledge, equipment, new technology, among others (Miguélez et al., 2011) and become stronger in the agricultural sector with low levels of production (Litina, 2016).

Regarding the relationship between income and informal institutional factors, it is shown that there is no link or level of dependence between these two variables. These results are in line with those obtained for the coffee sector; where it was not possible to establish the improvement of income despite the certifications and organisational changes of the small producer (Ibanez and Blackman, 2016; Snider et al., 2017). Therefore, further research is needed as this relationship is of one of the main objectives of fair trade to improve the quality of life of small growers (Fenger et al., 2015).

In theoretical terms, this research generates a contribution to the analysis of SV in agricultural cooperatives, from the perspective of informal institutions, taking the new institutional approach as a theoretical foundation. It also contributes to the discussion of base-of-the-pyramid business models including the factors to generate economic and social values.

In practical terms, the result of this research shows that successful cooperative models related to institutional factors, such as the one found in the banana industry, can be replicated in other agricultural products. It is a priority for the various members of the agricultural sector to continue with the strengthening of their networks and alliances, given the positive achievements obtained with the established links. For government entities, these results could encourage policies to promote further agricultural exports with both economic and social values. Finally, all agents should be aware that market pressures tend to regulate the development of inclusive businesses and the generation of social value in the members of the supply chain.

Among the limitations of this study is the number of cases analysed, which could be considered small for a representative study. However, it should be noted that with the data collected, the triangulation of the information and the comparison with other research it has been possible to conclude that the number of cases is sufficient to mainstreaming the results to other agricultural cooperatives with similar characteristics.

As future research, the comparison between cooperatives of large producers and cooperatives of small growers (base of the pyramid) could be an interesting analysis to establish conceptual differences in business models related to SV. Likewise, as a second phase of this research, it is suggested to replicate the research with a greater number of similar cooperatives of other products, in order to validate the propositions.

6. Conclusions

BoP businesses are a strategy which focuses on helping the poorest in emerging countries through the development of business models that create, simultaneously, economic and social value in its supply chain. There is consensus - independently of the origin and development of the concept - that this creation of economic and social value in businesses is SV.

The literature review showed three perspectives in terms of the origin: (1) industrial organisation and strategy framework; (2) stakeholders' perspective and (3) corporate social responsibility approach. In spite of this analytical confrontation, there is a growing interest for the debate and evolution of the share value concept. One of the steps in this evolution was at the centre of this research: “for the development of shared value in bottom-of-the-pyramid businesses, it is necessary to identify the informal institutions affecting their creation”. Networks and alliances as well as social capital have been identified as such institutions affecting value creation in cooperatives.

According to the results of the research, it was concluded that social capital as an informal institutional factor is generated by the strong networks and alliances (H4) that occur among small growers associated in cooperatives, as well as by the application of the principles of union and cooperation that govern the cooperative solidarity system (H7). This construction of social capital has helped small growers to face jointly their difficulties and improve their quality of life (second variable to measure the generation of social value) (H1). Therefore, it is concluded that team-work generated by social capital is essential (H3) and allows to verify that strong networks and alliances help to generate it (H6). It improves their own conditions, of their relatives and of the community through substantial changes in infrastructure (e.g. at homes, physical assets, irrigation systems, machinery, among others).

On the other hand, the generation of the economic value in inclusive businesses, measured through income, was not significant. Therefore, social capital (H2) and networks and alliances (H5) do not affect the income generated by the business model. Income varies according to several factors such as consumer's behaviour, supply and demand, sales planning and quotas and premium prices granted by certified bananas. There is also a huge dependence on the productivity of the farms and the environmental conditions of the moment.

Note

1. Interview and survey formats available upon request to authors.