Introduction

Social progress is based on the consumption of large quantities of energy and most of this energy is obtained from the burning of fossil fuels such as coal and oil. Globally, 65% of all primary energy consumed comes from fossil fuels (Arias and López, 2015). Although these non-renewable forms of energy have accelerated humanity’s technological development, they have the disadvantage of generating environmental pollution (Sari et al., 2019). Unrestrained consumption of these finite and non-renewable resources is now driving a need for new environmentally sustainable sources of energy. Examples of these new sources include industrial residues which are not only renewable but have the potential to replace fossil fuels (Ji et al., 2018). In fact, in recent years, hydrocarbons are increasingly being substituted for new, sustainable energy sources (Anggono et al., 2018; Hernandez et al., 2015; Pandey, 2019), a move motivated by growth in both industrial and domestic energy demand (Alarenan et al., 2020; Wu and Lee, 2020). Fossil fuel importing countries are becoming increasingly interested in reducing their oil consumption (Musa et al., 2018), and states, industries and consumers must now fully confront the need for renewable alternatives (Karner et al., 2017).

The energy strategies of first world countries now include projects to incorporate first and second generation biomass into renewable energy production (Campuzano-Duque et al., 2016). Biomass has become an important energy resource thanks to its low production cost (Amarasekara et al., 2017; Ludevese-Pascual et al., 2016; Manzoor et al., 2017) and its chemical, physical and, most importantly, calorific properties, and may constitute a viable alternative to coal for industrial energy generation and heating (Balasubramani et al., 2016). Furthermore, a move to biomass incineration may help to reduce overall greenhouse and acidic gas emissions (Kayo et al., 2016; Martinez et al., 2020; Murphy et al., 2016). Such a change would require adaptations to the energy supply chain in order to facilitate waste selection, homogenization and storage in order to ensure the availability of sufficient quantities to sustain the production process (Balasubramani et al., 2016; Busov, 2018; Robles et al., 2018; Rojas et al., 2018b). As such, protocols would need to be developed within the various productive sectors for recycling and the manufacture of new energy sources from the available biomass (Ahmad et al., 2020; Jain and Kalamdhad, 2020; Jalgaonkar et al., 2020; Verma and Kumar, 2020). Different industries produce different forms of waste which may be suitable for the production of biofuels and the generation of bioenergy (Go et al., 2019). Waste from the agricultural, forestry, textile and food sectors can be used to manufacture biofuel briquettes (Hansted et al., 2016; Romallosa and Kraft, 2017; Vargas and Pérez, 2018), and experimental examples range from the creation of solid fuel from fly ash (Guo and Zhang, 2020; Makela et al., 2016) to the combination of rice husks and pine sawdust (Nino et al., 2020). Energy can be generated from the incineration of a wide variety of biomass residues. Types of waste most commonly used are those generated by agriculture (e.g., seed husks, almond hulls, olive stones, grass), timber (e.g., wood chips, shavings, sawdust), food production (e.g., processing residues), the textile industry (e.g., clothing, shoes), along with those produced by forestry (e.g., pruning, cleaning) and the cultivation of woody crops (e.g., pruning, uprooting, fallen trees). In general, these forms of waste can be transformed into briquettes, chips or pellets (Patil, 2019).

Non-fossil fuel alternatives manufactured from waste

Briquettes

Briquettes are generally produced by the combination and compaction of lignocellulosic biomass in the form of organic raw materials (Arias and López, 2015). These include wood chips and shavings; different types of agricultural, textile and food waste (Hoyos et al., 2019; Rodriguez et al., 2017); residues from the production of timber, wooden panels, furniture and other products; industrial biomass residues, urban biomass residues (Sawadogo et al., 2018) and charcoal (Riuji et al., 2016). Briquetting results in a final product that has a greater density than its constituent materials. The process is also known as densification and has several advantages. Briquettes offer a superior space-to-weight ratio than chopped wood or chips, making transportation more efficient. Briquetting also reduces the moisture content of the material to less than 12%. Briquettes come in different shapes, but the majority are cylindrical with diameters ranging from 2 to 20 cm and lengths of between 15 and 50 cm. The thermal conductivity coefficient of briquettes is higher than that of wood: as a compacted material, it contains less air, which slows combustion. Heating potential depends on aspects such as shape, moisture content, density, calorific value and thermal conductivity coefficient (Martín, 2014).

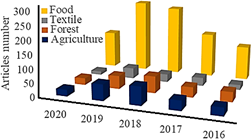

Figure 1 Published works concerning use of agricultural, forestry, textile, and food sector residues in the manufacture of briquettes. (The research was searched in the SCOPUS database and Web of Science, with the keywords: briquette; pellets; waste; biomass).

Given their physical, chemical and calorific properties, their ease of combustion, low humidity and high density, biomass briquettes represent an attractive form of biofuel for heating applications and the generation of electricity (Gangil, 2015; Tomeleri et al., 2017; Yank et al., 2016). The different raw materials used in the manufacture of briquettes produce different mechanical properties (Aransiola et al., 2019; Nhuchhen and Afzal, 2017). Different binding agents allow the production of briquettes of diverse shapes and sizes, and with varying degrees of firmness, compression, density, porosity, and other physical characteristics Briquetting also helps to minimize ash residue and improve other environmental aspects (Berastegui et al., 2017; D’Agua et al., 2015; Davydenko et al., 2014; Gendek et al., 2018). Briquettes incorporate non-toxic and non-polluting recycled materials and could be a form of environmental clean-up involving collection of waste materials. Furthermore, they offer a more appealing alternative to the felling of trees. Figure 1 illustrates the proportion of academic studies conducted on the use of agricultural, forestry, textile, and food sector residues in the manufacture of briquettes. Between 2015 to 2020, most studies have focused on the manufacture of briquettes from food waste, followed using agricultural residue, forestry residue and, finally, textile waste.

Pellets

Pellets are a similar but smaller-scale equivalent to briquettes, ranging from 6 to 7.25 mm in diameter and between 10 and 36 mm in length. They have an average moisture content of between 6 and 10%, an ash content of below 3%, a bulk density greater than 639 kg/m3, and a calorific value of around 4.7 kWh/kg (16.9 MJ/kg) (Arulprakasajothi et al., 2020; Lunguleasa et al., 2019; Ozturk et al., 2019). Effectively, they are a granulated form of biomass (Pinheiro et al., 2016; Spirchez et al., 2018).

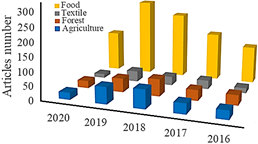

Figure 2 Published works concerning use of agricultural, forestry, textile, and food sector waste in the manufacture of pellets. (The research was searched in the SCOPUS database and Web of Science, with the keywords: pellets; briquette; waste; biomass).

Like briquettes, pellets are manufactured by the compaction or compression of waste materials (Durango et al., 2019; Marrugo et al., 2019). The main raw materials are residue from sawmills and the furniture industry, including rejected planks, sawdust, wood chips, offcuts, and dry shavings. These are compacted in a high-pressure mill, where the lignin content of the wood acts as a binder. Other forms of biomass, such as coal dust, can also be incorporated (Hidalgo et al., 2018). Wood pellets offer an attractive alternative to fuels such as coal, chopped wood, oil and other fossil fuel derivatives. They are also relatively cheap and easy to store, provide uniform combustion, have a low moisture content, and release smaller amounts of contaminant gases (Forero-Núñez et al., 2014). In particular, pellets constitute a more environmentally friendly option given their lower CO2 emissions than solid or chipped wood (Soto and Núñez, 2008). Figure 2 illustrates the proportion of academic studies conducted on the use of agricultural, forestry, textile, and food sector residues in the manufacture of pellets. Between 2015 to 2020, most studies have focused on the manufacture of pellets from food waste, followed using agricultural residue, forestry residue and, finally, textile waste.

Waste from different productive sectors in the manufacture of briquettes

Agricultural sector

Production of first and second generation solid, liquid and gas biofuels (Boutesteijn et al., 2017) from biomass is achieved by the processing of primary sources and agricultural and industrial waste from forestry, farming and livestock activities (Gutierrez-Macias et al., 2015), and from bushy and arboreal roundwood plantations. The process helps to improve agricultural sustainability and to protect natural resources such as water and soils. Production of biofuels using primary waste from agriculture and industry, roundwood plantations, and forestry, farming and livestock activities, particularly on underexploited soils, constitutes a viable option today (Weiss and Glasner, 2018).

Table 1 Agricultural waste as raw materials for the manufacture of biomass briquettes

| Waste/residue type | Calorific value (MJ/kg) | References |

| Sugarcane skin, Bamboo fiber | SCS: 17.23 BF: 16.92 | (Brunerova et al., 2018) |

| Hemp and sunflower fiber | 16.6 - 17.4 | (Alaru et al., 2011) |

| Sugarcane bagasse, sisal dust, cassava bran | 15 | (Muñoz-Muñoz et al., 2014) |

| Semi-dried banana leaves | 17.7 | (de Oliveira et al., 2014) |

| Maize | 15.8 | (Bautista-Ramírez et al., 2019) |

| Sugarcane bagasse; coffee, rice, and soybean husk; peanut and caster seed shell; wheat and rice straw; maize, sunflower, jute, mustard, and cotton stalks; coir pith; tobacco wastes | 13.4 - 20.7 | (Patil, 2019) |

| Moringa oleifera biomass | 15.87 - 23.31 | (Pereira et al., 2018) |

| Piñon (Araucaria angustifolia) residue | 17.6 - 18.6 | (Jacinto et al., 2016) |

| Rice husk and bran | 16.08 | (Yank et al., 2016) |

| Vine shoots, grape skins, stems, and seeds | 18.4 - 20.6 | (Rojas et al., 2018a) |

The climatic conditions of certain countries provide a favorable environment in which to adapt various annual and perennial plant species to the production of biomass which can then be transformed into bioenergy (Benie et al., 2005). However, the primary obstacle to the production of these biofuels is the relative scarcity of suitable agricultural land (Gao et al., 2019). The most abundant sources of agricultural biomass for the production of roundwood-, pellet-, briquette- and wood chip-based biofuels are residues from forestry activities, waste from the furniture industry, and the products of roundwood plantations (Clavijo et al., 2020).

Other important sources are cereals (maize, wheat, oats, barley), tubers (potato, beet, fodder turnip), and forestry biomass and its derivatives (lignocellulosic residues from harvesting and agro-industry). Each of these can be converted into liquid biofuels such as ethanol, methanol, and bio-oil. Oils from oil-seeds (safflower, linseed, sunflower, rape, castor, jojoba, jatropha), algae and other species, along with recycled vegetable oils and animal fats can be used to produce liquid biofuel such as biodiesel. Livestock manure; slaughterhouse waste; agricultural, agro-industrial and wholesale market residues; viticulture and winemaking residues; whey; and lignocellulosic residues can all be used to produce gas biofuels such as biogas. Nut shells and cassava flour have been incorporated as binders in the manufacture of briquettes (Chungcharoen and Srisang, 2020). The agricultural sector therefore plays a vital role as a generator of biomass suitable for conversion into biofuels and bioenergy (Javed et al., 2019; Samadi et al., 2020). Several agricultural sector waste types and their calorific values are presented in Table 1.

Forestry sector

Forestry activities generate large amounts of organic waste or biomass, which can be used for the production of biofuels that are less polluting than fossil fuel alternatives (Ayala-Mendivil and Sandoval, 2018). Biomass in the form of residues produced by tree plantations, pulp plants and sawmills (Table 2) can be used for the manufacture of briquettes or pellets. For example, sugarcane residue has been combined with pine sawdust and red angelim (Dinizia excelsa) to make briquettes (Fernandez et al., 2017). Forestry residues can be categorized as timber-yielding and non-timber-yielding. The first category includes usable woody materials (e.g., crown, branches, foliage, stumps, shavings, sawdust, offcuts, bark, sawn timber), while the second consists of the non-woody vegetation of a forest ecosystem (e.g., seeds, fibers, rubbers, waxes, rhizomes, leaves, stalks and stems, lichens, mosses, fungi, resins and soils) (Ayala-Mendivil and Sandoval, 2018).

Natural forest biomass refers to the organic material within a forest ecosystem, while dry residual biomass constitutes material generated by forestry activities and the timber industry. Wet residual biomass refers to biodegradable waste, including urban and industrial wastewater and livestock waste, primarily manure. Finally come the energy crops, which are grown solely as biomass for conversion into biofuel. These include roundwood plantations (de Bikuna et al., 2020; Jasiunas et al., 2020; Stolarski et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2020).

Conversion of forest residues into biomass has several advantages. In terms of energy generation, it has the potential to lower costs and yield a reduction in fossil fuel dependence. Environmentally, it means increased waste recycling, a reduction in the risk of forest fires, lower greenhouse gas emissions, and improvements to the quality of forest biomass. In socio-economic terms, biomass processing directly and indirectly creates jobs, provides the population with cheaper energy compared with that generated from fossil fuels, and results in lower rural to urban migration (Jackson et al., 2018; Ko et al., 2019; Liu and Rajagopal, 2019; Purohit and Chaturvedi, 2018).

Table 2 Forest residues as raw materials for the manufacture of biomass briquettes

| Waste/residue type | Calorific value (MJ/kg) | References |

| Wood chips (raw, torrefied and biochar) | 678.5 - 6.534 (MJ/h) | (Sahoo et al., 2019) |

| E. urophylla and S. parahyba bark | 0.0174 - 0.0192 | (Sette et al., 2020) |

| Piñón (Jatropha curcas) husk, sugarcane bagasse | 14.7 - 17.1 | (Maradiaga et al., 2017) |

| Sawdust | 16.0 - 52.8 | (Antwi-Boasiako and Acheampong, 2016) |

| Pine and beech sawdust | 15 - 18 | (Deac et al., 2016) |

| Sawdust and shavings (Pinus spp., Quercus spp.) | 17 - 18 | (Morales-Maximo et al., 2020) |

| Torrefied (TOB) and non-torrefied (NTB) briquettes | 19.6 | (Alanya-Rosenbaum and Bergman, 2019) |

| Pine needles (Pinus roxburgii) | 17.6 | (Mandal et al., 2019) |

| Palm oil mill sludge, sawdust | 19.8 | (Obi, 2015) |

| Khaya ivorensis (African mahogany) biomass, charcoal, and briquettes | 2.5 - 15.8 | (de Moraes et al., 2019) |

Table 3 Textile waste as raw materials to produce biomass briquettes

| Waste/residue type | Calorific value (MJ/kg) | References |

| Biological sludge, cotton and other microfibres | 16.3 - 23.5 | (Avelar et al., 2016) |

| Wood pulp, paper, and textile sludge | 8.85 - 10.55 | (Chiou and Wu, 2014) |

| Metallurgical coke, pregelatinized starch, polyvinyl alcohol | 28.4 | (Rajput and Thorat, 2020) |

| Cotton, polyester | 15.5 - 16.8 | (Nunes et al., 2018) |

| Polyester fibers, cotton, starch, lumps, and old rags | 14.9 - 20.9 | (Suvunnapob et al., 2015) |

| Cotton fabric and textiles | 15.70 - 16.26 | (Yasin et al., 2020) |

| Textile dyeing sludge and cattle manure | 4.11 - 15.86 | (Zhang et al., 2020) |

| Household waste, canary grass, plastic, and textile fraction | 18 | (Hedman et al., 2007) |

| Textile industry wastewater, rice straw | 10 | (Moliner et al., 2018) |

| Rubber elastomers, carbon black, metal, textile, zinc oxide, others | < 0.000198 | (Landi et al., 2018) |

Textile sector

Globally, the textile industry generates sales of at least US$ 2.5 trillion and provides at least 75 million jobs; however, despite high demand, profit has declined due to price differentiation (Yaghin, 2020). The industry is also responsible for 10% of carbon emissions globally, produces around 20% of the world’s wastewater, and consumes vast amounts of energy. Less than 1% of the material produced by the textile industry is recycled, resulting in a loss of at least US$ 100 billion in raw materials each year. Around 85% of textiles are sent to landfill or incinerated, and 73% of clothing destined for reuse is lost before it can be processed. Greater recycling and reuse of textile waste would contribute considerably to addressing the environmental issue (Calvo and Williams, 2019; Lucato et al., 2017; Shevchenko et al., 2019).

The textile industry is one of the most polluting and consumes large amounts of resources, including raw materials (both natural and synthetic), water, transportation, and treatment of waste, primarily in the form of primary and biological sludge from wastewater treatment. For example, India’s textile and clothing industry exported 12.4% of the global total in 2017, generating textile waste of which only around 8% was recycled (cotton and artificial fabrics and threads, woolen and silk fabric, makeup and clothing) (Jafari, 2019; Kim, 2019; Navone et al., 2020). Furthermore, textile sludge varies in composition, but tends to contain high levels of organic material, nitrogen, phosphorus and micronutrients, as well as dyes and heavy metals (Avelar et al., 2016; Yuvaraj et al., 2020). Disposal of textile waste represents a high cost to companies, and repurposing of the various residue types by transforming them into valuable biofuel sub-products (Table 3) constitutes an attractive option. An example of this is the manufacture of briquettes from solid textile waste (Avelar et al., 2016), which would go some way towards mitigating environmental damage (Avelar et al., 2016; Nunes et al., 2018; Piribauer and Bartl, 2019; Turemen et al., 2019). Another means of classifying biomass from the textile sector is to differentiate between post-industrial waste (material left over from the processing and cutting of fabrics), pre-consumption waste (garments which do not reach the market due to defects or which are discarded by the manufacturer), and post-consumption waste (finished material that has reached the end of its usable life).

Food sector

A review of the relevant literature reveals considerable variation in definitions and classifications of food waste. One debate concern whether food waste should refer exclusively to the edible parts of food or to inedible parts as well. Another questions whether food waste should be limited to materials destined for human consumption or extended to waste generated along the supply chain, given the multiple potential sources of biomass provided by the food sector. The most widely accepted approach is to consider those edible foodstuffs discarded early in the supply chain; that is, during production, post-harvest, and industrial processing. Also included are those edible and inedible food parts that are removed from the supply chain, such as those destined for composting, anaerobic digestion (Gustavsson et al., 2011), or bioenergy. One example of the latter is the manufacture of briquettes using bean husk waste from coffee production, achieving an activation energy value of between 104.90 kJ/mol and 345.2 kJ/mol (Setter et al., 2020). Many authors define food waste as goods produced for human consumption but which, for various reasons, are discarded or used for other unrelated purposes (Alexander et al., 2017; Buzby and Hyman, 2012; Griffin et al., 2009).

Fresh vegetables, for example, are considered food waste (Table 4) if they reach maturity and are not harvested for economic reasons, as a result of damage caused by animals, or due to climatic factors, poor seed quality, excess production, insufficient growth, or unappealing appearance (Ayerst et al., 2020; Cattaneo et al., 2020; Narciso, 2020; Newman and Tarp, 2019). They are also considered food waste if they are harvested but are subsequently discarded as unsuitable for human consumption due to chemical contamination, excessive or insufficient pesticide use, infestations, infections, transport and storage issues, or non-compliance with quality or aesthetic standards (Frison and Clément, 2020). Animal products, including those resulting from human food production, are considered food waste if they are destined for energy valorization, anaerobic digestion, or composting. It is during the industrial processing stage that the largest quantity of food waste is produced, including that resulting from production errors and/or changes; excess production; non-compliance with standards; poor management, handling, storage or transportation (within facilities); and inedible materials left over from the process. Globally, between 20 and 40% of food waste is generated during the manufacturing stage (García-García et al., 2017; Masud et al., 2020; Qi et al., 2020; Teigiserova et al., 2020; Westerholm et al., 2020).

Perspectives on waste and challenges for the future

According to estimates by the International Monetary Fund, global economic growth will rise from 2.9% in 2019 to 3.3% in 2020, driven by manufacturing and international trade. The global urban population has grown rapidly since 1950, increasing from 746 million to 3.9 mil millions in 2014 (Nations-United, 2014) and to 7.7 mil millions 2019 (Nations-United, 2019). This growth and development has had negative impacts on climate change, the risk of international conflict over access to strategic resources, and the growing threat of epidemics and pandemics (Acikgoz and Gunay, 2020; Lomborg, 2020; Sarkodie et al., 2020a; Sarkodie et al., 2020b).

Global waste generation is expected to grow from 2 mil millions tons to 3.4 mil millions tons by 2050 (Kaza et al., 2018). According to the World Bank, the East Asia and Pacific regions generate 23% of the world’s waste, while 34% is created by high-income countries. This waste consists of plastic (12%), green foods (44%), glass (5%), metal (4%), paper and card (17%), rubber and leather (2%), wood (2%), and other materials (14%). According to the United Nations, treatment and disposal of waste is achieved by composting (5.5%), incineration (11.1%), controlled landfill (3.7%), unspecified landfill (25.2%), sanitary landfill (with landfill gas collection, 7.7%), open dump (33%), recycling (13.5%), and other solutions (0.3%). These projections and figures are a clear illustration of the startling accumulation of waste around the world and the short-term impact that this is having on the environment. Development and implementation of improved farming practices could drive a reduction of at least 30% in waste generation globally, including through the conversion of these residues into new energy products that offer a valuable ecological alternative to conventional fossil fuels (Moustakas et al., 2020; Shariat Panahi et al., 2020; Shirzad et al., 2019).

Furthermore, there is a need for the diverse legislation of emerging and developing countries to be brought into line with more demanding waste treatment standards, such as those of Europe, North America and Japan (Mutz et al., 2017). Many countries around the world have seen an opportunity to develop strategies based on the technological and economic model of the circular economy (Momete, 2020); that is, to reduce (reduce the volume of waste generated by, for example, the agricultural, forestry, textile and food industries, as well as the cost of collection and treatment of waste), to reuse (cleaning and repair of a discarded product so that it can be reused), and to recycle (collection and transformation of waste into secondary raw materials) (Dau et al., 2019; Rosa et al., 2020).

Table 4 Food waste as raw materials for the manufacture of biomass briquettes

| Waste/residue type | Calorific value (MJ/kg) | References |

| Charcoal, wild cassava, bioethanol | 17.7 - 19.7 | (Gesase et al., 2020) |

| Recovered wood, food waste | 19.5 - 21.3 | (Myrin et al., 2014) |

| Molasses as a binder | 23.54 - 29.21 | (Wang et al., 2019) |

| Food waste | 0003 - 0.009 | (Elkhalifa et al., 2019) |

| Artichoke stalks, wheat straw | 15.6 - 17.71 | (Titei et al., 2019) |

| Food processing sludge | 18.59 - 25.70 | (Chiou et al., 2015) |

| Jackfruit peel waste | 20.1 - 22.6 | (Pratiwi et al., 2019) |

| Food waste, molasses | 25.2 - 32.3 | (Zhai et al., 2018) |

| Olive oil waste | 31.8 | (Arvanitoyannis et al., 2007) |

| Coconut fiber, rice husk, mineral coal | 0.0158 - 0.0239 | (Hoyos et al., 2019) |

The success of the circular economy model depends on appropriate management of waste. This includes promotion of product repair and reuse, increases in efficiency in terms of energy and resource consumption, increases in the recycled content of new products, boosting of high-quality remanufacturing and recycling, reductions in carbon footprint and in the use of water and other crucial materials, the elimination of single-use products and of planned obsolescence, a move towards business models based on products as services, promoting digital transformation and traceability of products and materials, and promoting efficient and environmentally sensitive economic growth(Çetinay et al., 2020; Cramer, 2020; Jabbour et al., 2020; Kokkinos et al., 2020).

Conclusions

Humanity is currently facing serious environmental challenges. Advancements in technology, population growth, urbanization and increased energy consumption are producing vast quantities of waste, and the use of environmentally harmful processes to meet energy demands are driving climate change and threatening the world’s ecosystems. The need to formulate and implement new programs of waste repurposing, sustainability and renewable energy production is now more urgent than ever. Significant advances have been made in these areas in recent years, but far more is required if we are to address the environmental challenges of our time in any meaningful way. Future research should address Industry 4.0 and the green and circular economies, placing the focus on utilization of agricultural, forestry, textile and food industry waste, the development of new waste-based businesses, the generation of energy by alternative means, and the global alignment of production, recycling and waste repurposing policies.