Introduction

The case of African Swine Fever (ASF) in Asia has been unprecedented with outbreaks occurring around many countries, significantly impacting animal health and welfare, the agricultural economy and food security (Costard et al., 2009; FAO, 2020; Tian and von Cramon-Taubadel, 2020). While ASF does not pose direct risk to human health, its highly contagious and fatal characteristics affecting both young or old, and domestic and the wild boar population could lead to severe devastation of the pig industry (Costard et al., 2009; Costard et al., 2013). African Swine Fever has ravaged the swine industry of both the Western (1960-1995) and Eastern Europe (2007-2018) (Cwynar et al., 2019; Lu et al., 2020), and has caused more than a million pig deaths in China since severe outbreaks occurred in 2018, signalling fear and unprecedented spread among other countries in Asia (Estienne, 2019). Inevitably enough, many Asian countries have been affected since, including Mongolia in January, Vietnam in February, Cambodia in April, North Korea in May, Laos in June, Myanmar in August, and South Korea in September, among others including the Philippines as the 9th country affected (Pig Progress, 2019; Estienne, 2019; FAO, 2020; Kim et al., 2020; Parrocha, 2020). Record breaking increase in the number of countries affected has continued to occur since 2005 to 2018 (Rozstalnyy and Plavšić, 2019). Since the ASF DNA virus is complex being unusually related to other viruses, no effective vaccine has yet been de veloped (Costard et al., 2013), thus calling for a comprehensive approach to contain and control its impact.

Due to the potential catastrophic impact of ASF on the country’s swine industry, the President of the Philippines signed Executive Order No. 105 in February 21, 2020 “creating a national task force to prevent the entry of animal-borne diseases, contain and control the transmission thereof, and address issues relating thereto”, and mandating the “Department of Agriculture, through the Bureau of animal Industry to control and eradicate dangerous communicable diseases of domestic animals” (Offical Gazette, 2020). Towards the end of 2020, The Philippines has seen several thousands of deaths and/or mass culling of pigs to control the spread of ASF particularly in Luzon in the north but has also affected Mindanao in the southern part of the country (Parrocha, 2020). The Philippines is among the top pork producers worldwide with a close to ₱200 billion pig industry of about 12.7M pigs (DOST-PCAARRD, 2016; PSA, 2020). Of this about 65% is considered backyard or those pigs normally raised by smallholder farmers with seemingly limited access to feed supply, equipment, and facil ities, and veterinary health resources. The practice of swill feeding is not uncommon given the several and widely available sources including kitchen leftovers, hotels, restaurants, and the like.

The Eastern Visayas Region (Region VIII) in central Philippines where this study was conducted is still free of ASF but the risk is high considering the volume of pigs that arrive in this region both coming from Luzon (north) and Mindanao (south) pig producers. Thus, the Department of Agriculture and authorities in the region have prompted significant steps to prevent the entry of ASF including the release of relevant Executive Orders from different provincial governments to monitor and/or ban entry of live pigs, pork and pork products from different entry/exit points as well as timely reporting of pigs that manifest ASF-like symptoms (Quirante, 2019). The Bureau of Animal Industry has also earlier rolled out the “1-7-10 Protocol” for culling management, surveillance, and reporting, as well as the BABES campaign which stands for: Ban pork imports from confirmed ASF-affected countries; Avoid swill feeding; Block entry at major seaport and airports, especially international ports; Educate our people; and lastly, Submit hog blood samples (DA Communications Group 2019; Meniano, 2019). Region VIII is a potential market from among large pig producers outside of the region considering its low pig inventory in the country (3.2%; PSA, 2019). The demand for pork in the Province of Leyte is substantially favourable as Leyte ac counts for most slaughtered pigs within the region (PSA, 2018).

Preventing further spread of ASF from the initially affected areas appears to be the core strategy to contain the economic losses caused by ASF (GAIN, 2019). The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) through the Agriculture and Consumer Protection Department emphasizes early reaction, detection and notification including the application of strict biosecurity measures. This also includes improved husbandry prac tices, disinfection and good surveillance and monitoring of live pigs being transported (FAO, 2020). Stringent compliance with biosecurity measures and cooperation with government initiatives are key strategies to prevent introduction and contain the impact of ASF. The aim of this study was to determine and understand the current situation, readiness and examine the biosecurity practices of backyard pig farmers within the City of Baybay, Leyte, Philippines. Results of this study could influence decision makers both as pig farm owners and government officials in facing the challenges posed by disease outbreaks.

Materials and methods

Location of the study and sampling procedures

The study was conducted between September 2019 to February 2020 about a year after the significant outbreak of ASF occurred in the country. The City of Baybay in the Province of Leyte, is the second largest city within the Eastern Visayas region (Region VIII) composed of at about 92 barangays, 24 of which are urban and 68 are rural, and a home to a population of about 110,000 (PSA, 2017). There are only a few commercial pig farms making backyard or smallholder type of pig production a major livestock activity covering about 11,000 pig population. Following recommended sampling procedures, at least 350 pig farmers were required at 95% level of confidence and 5% margin of error after considering about 4,100 current backyard pig raisers (The Research Advisors 2006; Fosgate, 2009; Andico and Peña, 2019). The farmer respondents were randomly selected and proportionally allocated per barangay from a given population of backyard pig raisers provided by the local agriculture office. The study was approved by the Student Research Committee of the College of Veterinary Medicine, Visayas State University.

Survey questionnaire and conduct of interview

A systematic questionnaire was constructed and modified following previous research by Andico and Peña (2019) including earlier studies on similar topic (Ribbens et al., 2008; Alawneh et al., 2014) (Appendix). Among the questions included were the pig farmers’ socio-demographic information, pig production and health management, biosecurity practices, and farmers’ knowledge of ASF. The questionnaire was constructed in English and translated into the local dialect (Baybayanon/Cebuano) for ease and convenience during the one-on-one interview at the respective residence of the farmer respondents with prior verbal consent. Any information that has the potential to identify the farmer-respondent was handled with confidentiality and was not included in the analysis to protect the privacy of respondents. In the event the first respondent was not available or refused to participate, the next available backyard pig raiser closest to that respondent was interviewed instead. The actual interview completed about 15 minutes per respondent.

Data management and statistical analysis

All data were encoded in and analyzed using Microsoft Office Excel with XLSTAT Basic (version 2020.1.3) installed for multiple correspondence analysis (MCA), agglomerative hierarchical clustering (AHC) and parallel coordinates plots (PCP), following procedures found in the XLSTAT Support Center and as previously described (Andico and Peña, 2019). From the questionnaire, variables relating to knowledge on ASF, and biosecurity practices were analyzed separately. Descriptive statistics on farmers’ socio-demographics and pig production general characteristics were also generated, accordingly.

Results and discussion

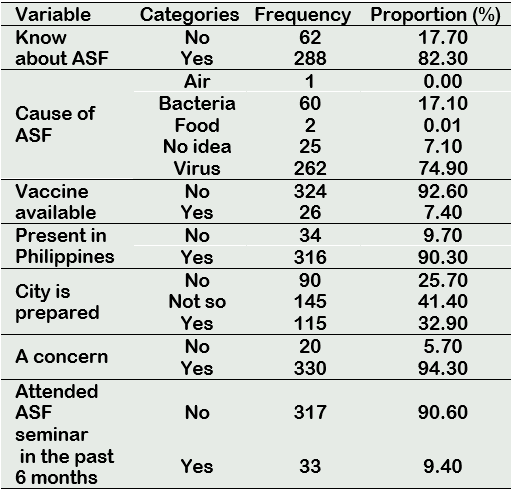

All farmers who were initially included in sampling responded providing us with sufficiently robust data to proceed with the evaluation and characterization of the different aspects of the level of preparedness and biosecurity practices of backyard pig farmers against potential ASF outbreak and other swine diseases in Baybay City, Leyte. Apparently, at least three quarters of pig farmers signified awareness of ASF (82.30%) and have correctly identified ASF as a viral disease (74.90%, Table 1). Almost all the respondents are aware that ASF is already present in the country and that a vaccine for prevention does not exist, thus a major concern if an outbreak occurs. Interestingly, despite attendance to seminar on ASF, almost half of the farmer respondents were convinced that the city is not likely prepared in the case of an ASF outbreak (Table 1).

Table 1 Summary statistics of the farmer-respondents’ knowledge about the African Swine Fever (ASF)

n=350; ASF, African Swine fever.

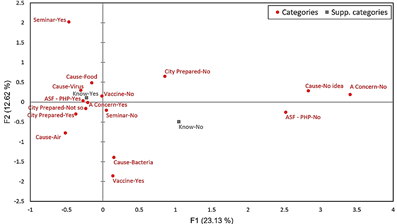

Figure 1 Multiple-correspondence analysis solution of the farmer-respondents’ knowledge about the African Swine Fever (ASF).

Figure 1 shows the MCA solution for the variables regarding actions taken by the respondents to control and prevent pig diseases. Briefly, those respondents who responded having knowledge of ASF were the same respondents who answered correctly in terms of the cause, and the presence, including participation on a seminar about ASF (upper left quadrant), while, those who responded being not aware of ASF have not attended any seminar on ASF nor were aware of the presence of ASF in the Philippines (lower right quadrant).

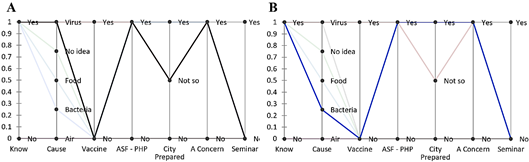

Following AHC, six clusters were generated characterizing the farmer-respondents’ knowledge about ASF. Almost half (46.70%) belong to Cluster 1 (black) and is characterized by pig farmers who have signified knowledge about ASF, its cause, presence in the Philippines, that it is a concern, but is not so convinced that the city is prepared of potential ASF outbreak (Figure 2A). Almost similar features appear to characterize Cluster 3 (blue, 33.43%%) except that these respondents believed that ASF is caused by bacteria and that the city is prepared despite having not attended any seminar on ASF (Figure 2B).

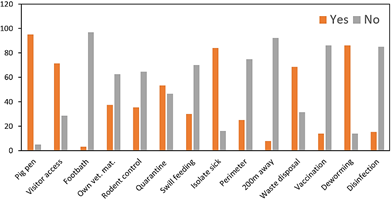

Figure 3 provides summary statistics of some pertinent biosecurity practices of backyard pig farmers. Despite the remarkably high proportion of farmers who provide pens for their pigs, there are still some who do not (4.90%). While deworming is heavily practiced, the opposite was true with vaccination. Many pig farms are freely accessible to visitors, no effective footbath, nor perimeter fence provided with only less than 10% of the pig farms were at least 200m away from the household. About 30% still practiced swill feeding and a sizable portion do not necessarily own veterinary materials for use on their farms.

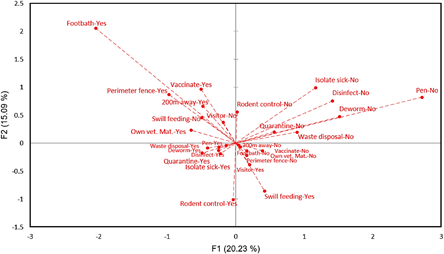

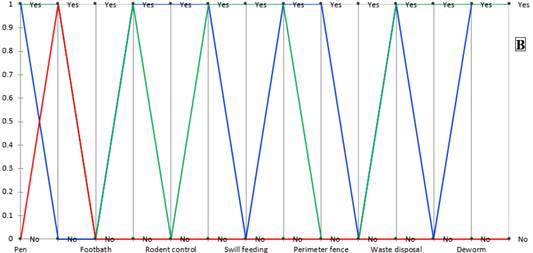

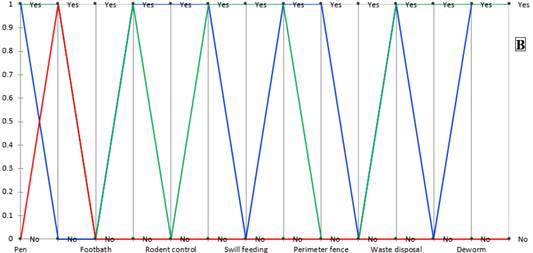

Figures 4 and 5A show the MCA solution, and dendrogram generated by AHC of the farmer-respondents’ biosecurity practices and pig health management in Baybay City, Leyte, respectively. Of the three clusters generated, C2 (green) is by far the largest (58.29%), followed by Cluster 1 (blue, 38.00%) and finally Cluster 3 (red) at 3.71%. The biosecurity practices between these clusters are plotted accordingly in Figure 5B which highlights Cluster 1 (38%) with good biosecurity practices.

Figure 2 Parallel coordinate plots highlighting Cluster 1 (2A, black, 46.7%) and Cluster 3 (2B, blue, 33.43%) showing six clusters of farmer-respondents’ knowledge about African Swine Fever (ASF).

Figure 4 Multiple-correspondence analysis solution of the farmer-respondents’ biosecurity practices and pig health management.

Figure 5 Dendrogram generated by AHC (A) and parallel coordinate plots (B) describing three clusters (C1= blue, 38.00%; C2= green, 58.29%; & C3= red, 3.71%) of the farmer-respondents’ biosecurity practices and pig health management.

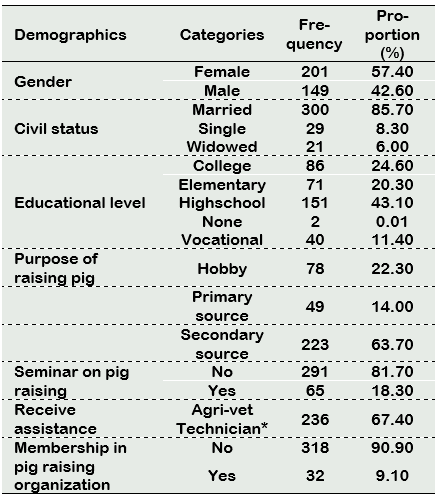

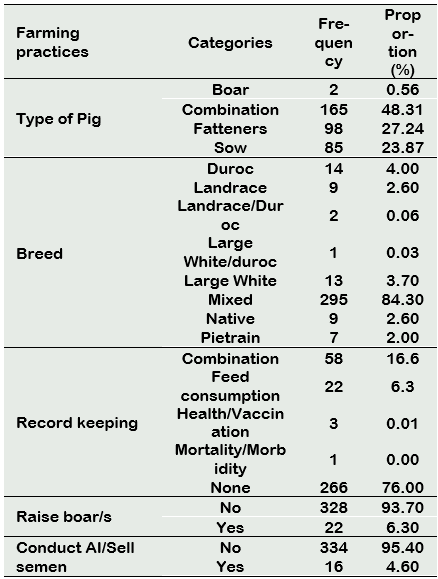

Table 2 provides summary statistics of the demographics of the farmer-respondents. Apparently, there were more females than males, and most of the pig raisers are married. Nearly half of the farmer- respondents (43.10%) have reached high school while 63.70% answered secondary source of income as the purpose of pig raising. Only a small portion have attended seminar on pig raising (18.3%) in the last six months, in the same way as membership in a swine raising organization (9.10%). In addition, the average age of the farmer-respondents was 45.67 ± 0.64 with about 8.21 ± 0.39 years of experience in raising pigsOn Table 3 is a short description of the farming practices by farmer- respondents. Nearly half of the respondents (48.31%) raise a combination of different classes of pigs with a majority using a mixed breed (84.30%). A few farmers raise boars for artificial insemination or selling semen. Good record keeping does not exist in 76% of the farms. The average number of pigs raised by each pig farmer is 5.24 ± 0.30 heads.

The potential devastation that ASF may cause to the pig industry requires an active involvement of pig growers in the community as they are in the frontline of detection, notification, and the application of strict biosecurity measures. Moreover, as pig farmers have different husbandry and health management practices, it is imperative that the government should take a proactive role in surveillance and monitoring of hygiene, proper waste disposal, swill feeding, and the conduct of related seminars on best practices and pig diseases, among others, to raise awareness within the community. In the case of the City of Baybay, Leyte, at least a longstanding city ordinance (M.O. No. 004 2004) already exits highlighting systematic and ecologically sustainable programs to be adopted in all pig raising projects. However, how this ordinance is being enforced or practiced by concerned stakeholders may need to be revisited.

Results of our current study demonstrate several key areas in pig raising activities that need to be reviewed and LGU’s active support is important not only to improve production targets but also increase the level of preparedness among backyard pig farmers in the case of disease outbreaks like the ASF. While ASF could drastically affect large and commercial pig production businesses (Costard et al., 2009), significant losses could easily railroad small pig producers commonly known in the Philippines as backyard pig farmers apparently due to poor preventive/control measures and biosecurity in this type of production (Edelsten and Chinombo, 1995; Costard et al., 2009). As ASF can wipe out a significant fraction of the pig population, the risk it poses against food security can be difficult to imagine. Pork is still one of the most widely eaten meat globally and many countries rely heavily on the pig production trade providing significant contribution to many countries’ gross domestic product. In 2011, when an ASF outbreak occurred in Isoka district of Zambia in Africa, the pig population decreased by at least 50% (Komba et al., 2014), let alone the possible rise in the price of locally produced pork as a result of reduction in pork supply (McOrist, 2019). Thus, vulnerable regions however small should engage in programs to empower both animal professionals and down to common pig growers to embrace awareness and readiness against potential disease outbreaks.

Interestingly, most pig farmers appear to be clearly knowledgeable of ASF along its presence as an active threat in the Philippine swine industry (Table 3). It has been noted that most of the farmers have access to TV, newspapers, and related materials as sources of information about the ASF. This could be a good start to strengthen further the implementation of relevant programs for the prevention and control of swine diseases. Since, nearly half of the farmer respondents represented those cluster who are not so convinced that the City of Baybay is prepared in the case of an ASF outbreak (46.7%; Figure 2A), the LGU concerned may take this as a priority to engage in different education campaigns to heighten the promotion of ASF awareness within the locality particularly among those engaged in pig farming. When the first ASF case was reported in the Philippines in about September 2019 (McOrist, 2019; WAHID, n.d.), samples require further confirmation so that appropriate measures can be applied. Moreover, this is compounded by the fact that the rate of spread depends on multiple factors many of which are yet to be understood fully (Schulz et al., 2019).

In terms of pertinent biosecurity practices of backyard pig farmers, the practices that need to be highlighted include vaccination, provision of a suitable footbath, perimeter fence, rodent control, and most importantly swill feeding. Nevertheless, it was notable to observe that the farmer-respondents have good biosecurity practices in general. However, there are still about 5% who do not provide proper shelter for their pigs (Figure 3) while the importance of vaccination, swill feeding and the provision of a footbath where possible need to be emphasized for Cluster 2 (58.29%; Figure 5A) of pig farmers. In fact, swill feeding alone is still practiced by closed to 30% (Figure 3) which is quite alarming considering that the introduction of ASF into the country could have likely started from contaminated meat leftovers and waste food products fed to backyard pigs (Beek, 2019). This is almost similar in the case of ASF outbreak in Brazil in 1978 which was suspected to be due to food waste introduced by tourists from infected countries (Lyra, 2006). While biosecurity in general should be attainable and reasonable, there are complex factors that need to be considered for effective implementation particularly when applied to field settings (Anderson, 2010). There are practical variables including but not limited to budget, equipment, facilities, educational background, and personnel’s understanding and attitude against disease spread and prevention (Anderson, 2010; Simon-Grifé et al., 2013). In terms of attitude toward implementation of biosecurity programs, it appears that the economic cost and benefits associated with implementation of such programs need to be clear in the first place and how these measures play along with mandatory rules (Gunn et al., 2008). In fact, one of the reasons pig farmers and traders may have a negative atitude and less cooperation with authority towards biosecurity measures is the associated costs.

It is quite typical for backyard pig raising activities to be considered as a secondary source of income as demonstrated in the result of the study (63.70%; Table 2). Many of these farmers may still be engaged in other farming activities while the limited land and the capital requirements may also prohibit them to engage in commercial production. Given the average age of farmers at 45.67 ± 0.64 years, this was apparently reflected also with their relatively long experience (8.21 ± 0.39 years) in pig raising activities. This could be taken as an advantage by the LGU as these farmers demonstrate their experience and skills in pig raising given their long engagement. Quite surprisingly though, only a small portion of the farmers have answered attendance to pig raising seminars as well as membership in swine raising organization (Table 2). This should be promoted as participation and involvement to relevant education activities and organization is both helpful and advantageous (Andico and Peña, 2019). The problem of record keeping in the farm also needs to be addressed as most pig farmers (76%) do not keep records of their farming activities (Table 3). A portion of farmers are also engaged in maintaining a boar allowing them to sell semen which again could funnel the transmission of diseases (Table 3). Overall, it appears that bottomline measures directed towards early detection, timely reporting, rapid response and coordination of various stakeholders at all levels, on top of good animal husbandry, health management and biosecurity (Swai and Lyimo, 2014; Yun, 2020) must be given priority to ensure readiness in the case of potential ASF outbreaks and other swine diseases of economic importance.

Conclusions

Pig farmers in Baybay City, Leyte are mostly aware of the African Swine Fever as a viral disease present in the country. However, despite the seemingly acceptable biosecurity practices of pig farmers with close to 95% who signified ASF as a concern or threat to the pig industry and food security, only a third believes that the City is prepared to a potential ASF outbreak. Swine stakeholders of the city should take into consideration efforts geared towards preparing and training pig farmers on disease monitoring and surveillance, and improving further its biosecurity practices perhaps with special focus on bioexclusion in order to prevent the entry of the ASF virus into the city. Similar studies should be conducted to nearby cities and municipalities (local government units) particularly near entry and exit borders of the Eastern Visayas region.