Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Comuni@cción

Print version ISSN 2219-7168

Comuni@cción vol.11 no.1 Puno Jan-Jun 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.33595/2226-1478.11.1.375

Original article

Leadership, culture and inclusive practices from the perspective of management teams of educational establishments

1 Universidad de Atacama, Sede Vallenar, Chile.

2 Universidad Santo Tomás, Chile.

3 SATTVA Consultores Educacionales.

4 Universidad Central de Chile.

Managing diversity is one of the great challenges of education today, a speech promoted in Chile by the entry into force of Law 20.845. Considering the role of management in the construction of inclusive educational communities, a study with a qualitative approach is presented which objective was to investigate the meanings that the members of management teams of two educational establishments give to leadership and inclusive leadership. These last as elements that favor practices inclusive and promote the development of inclusive cultures. The findings show the identification of the concepts of participation and collective decision-making as central elements of inclusive leadership, emphasizing the centrality of inclusive values in the creation of inclusive cultures. In conclusion, the inclusive practices identified seem to be only a first step in a much broader and deeper reflection-action for a necessary holistic and strategic vision of inclusion.

Keywords: Educational inclusion; Leadership; Inclusive leadership; Inclusive cultures, Management teams

INTRODUCTION

Currently, one of the great challenges the school faces is managing the diversity of its students (Gómez, 2012). Hence, from there the concept of educational inclusion becomes relevant, which can be understood from different perspectives and, in general terms, refers to an opening of school systems to the social and cultural diversity of its students, expanding the concept of inclusion to the diversity. This implies assuming that including is living with the entire range of diversities, beyond considering only the special educational needs (Rojas, Salas, Falabella and Guerrero, 2018).

In this context, being a reality in educational establishments the convergence of diverse students and families., the centers have to adopt strategies and methodologies that facilitate the participation of the whole community and whose impact is reflected in enriching the curriculum and the achievement of more significant learning by the students.

In this way, assuming an inclusive perspective implies not only the incorporation of inclusion as a value or seal within the Institutional Educational Projects (PEI), but also entails a paradigmatic and cultural change. From here, the starting point is to generate the participation of the entire community and implement inclusive practices that allow to respond the system demands. Following Valenciano (2009), achieving inclusive schools means moving from the integration towards inclusion, based on the right to education, equal opportunities and participation.

In this order, the role of management teams is preponderant to carry out processes of improvement and transformation of schools, since it is known that the school management is the second factor in-school that most affects academic outcomes (Leithwood and Day, 2008). According to the argument of Sarto and Venegas (2009), if leadership is essential in the school management of educational institutions, then it is determinant in inclusive projects. Besides adhering to inclusive values, the management teams must carry out an efficient management that is consistent with those values.

However, a research in leadership from an inclusive approach does not have a profuse development (Valdés and Gómez, 2019), and this becomes especially relevant because, according to Rojas et. al. (2018), management teams are the key actors in the consolidation and exercise of inclusion within schools and, therefore, require nurturing leadership and improvement processes that contribute to generating participatory communities and inclusive cultures.

Particularly in Chile, the current Law 20,845 of School Inclusion (which removes the barriers to student selection in schools that receive public funding, ends with the copayment and prohibits the profit of the establishment holder), has fostered diversity and social inclusion by declaring inadmissible a series of discriminatory practices in the processes of admission and expulsion of students. Thanks to this, inclusion is seen as a right, and not as a seal that educational establishments may or may not opt for. Unfortunately, Rojas et al., (2018), report that although the general principles of the inclusion law are shared, there is limited knowledge about that law as it is associated with the principles of decree 170 and the integration of children with special educational needs.

Therefore, it is necessary to understand inclusive leadership as a collective process that tends to produce a particular result: inclusion. In this way, an inclusive leadership context would be characterized by the active participation of all individuals or groups in the design of policies, decision-making and other processes that imply influence or power. These aim to involve all people in the schools and communities offer; promoting horizontal relationships between members of the organization; the tendency to eliminate asymmetric power relations; and, the achievement of inclusion as the main objective conceived as a collective task (Ryan, 2016).

To realize this ideal of inclusion within schools, Booth and Ainscow (201 5 ) consider three dimensions: a) inclusive cultures, referring to the creation of a welcoming community that provides security while promoting collaboration and participation; b ) inclusive policies, referring to institutional support, and; c ) inclusive practices, reflecting culture and policies, which objective is to ensure activities and actions, by mobilizing and executing resources to promote participation while considering the diversity of students.

According to these ideas, inclusive practices acquire special relevance when speaking of inclusive leadership, since this would be concretized and materialized in tangible practices, which main focus is the mobilization of resources and people for the achievement of the greater good that is inclusion. Next, Table N° 1 summarizes the inclusive practices identified from different theoretical references.

Table 1 Inclusive practices identified by different authors.

| Murillo, Krichesky, Castro and Hernández (2010) | Identify and articulate the school's vision Developing people Focus on teaching-learning processes Encourage the creation of professional learning communities Promote collaboration between school and family, improving the development of educational cultures in families Expand the social capital of students valued by schools Strengthen inclusive school culture |

| Ryan (2016) | Communicate with others Promote critical learning Inclusive school-community relations Advocating strategically |

| Valdés and Gómez Hurtado (2019) | Leading the ideal of inclusive education Managing diversity Build inclusive community Developing professional skills Promote inclusive values Establish a common language Organization of the educational institution Collaboration by everyone |

| Leiva, Gairín and Guerra (2019) | Distribute functions among the existing members of the institution Modify application of coexistence rules from the punitive to a rights and due process approach Inclusive practice that associates collaborative work and the School Integration Project Train teachers and non-teachers in diversification of teaching as a gradual process of formation and execution of the Exempt Decree 83, of the year 2015 Train teachers through learning experiences or situations Accompaniment of the director and teachers to students with difficulties Focus support for a student with a disability, from physical access and access to the curriculum Raise awareness among teachers, students and parents to understand inclusion from respect and diversity |

Source: Own work.

On the other hand, it is necessary to get deep into the concept of inclusive culture, where school management is considered a key element in the construction of schools with an inclusive culture, understanding that it is one which is focused on:

Creating a safe, welcoming, collaborative and stimulating community in which everyone is valued, as the fundamental foundation for all students to have the highest levels of achievement. It aims to develop inclusive values, shared by all the faculty, students, school board members, and families that are passed on to all new members of the school (Booth & Ainscow, 2000, p. 16)

Consequently, León-Guerrero (2012) recognizes the close relationship between school leadership and inclusive school, placing leadership and specifically inclusive leadership as the link between both constructs. Thus, among the central ideas of his proposal he emphasizes that leadership in a center is not exclusive to the manager or management team.There are two fundamental areas, which are indissoluble, and which must be assumed by the directors of the centers: management and leadership; the support and momentum of the management team is essential to improving centers. Also, not all leadership styles are effective in helping centers to achieve an inclusive culture.

These approaches are subsequently reinforced by Booth and Ainscow (2015) themselves, who highlight the importance of inclusive values and participation. Pointing out, among other ideas, that the change in schools becomes an inclusive improvement when it is based in inclusive values. Also, doing the right thing involves relating different school practices and actions with values; and, participation involves learning, playing or working collaboratively with others.

In this way, leadership in its articulating role should be characterized by being an effective and transformative leadership that is committed to the values and principles of inclusion. For this, it can create and maintain the conditions that guarantee this collaboration and learning (Ainscow and Howes, 2006). Only in these terms, the leadership would align with the claims of society today and the legislation in force, through being at the service of creating a diverse, respectful community, without abuse of power, whose impact is social and transformational, in order to advance in a more egalitarian society (Rojas et al., 2018).

From this view, and considering the importance of the leadership role in developing inclusive schools, this study aims to investigate the meanings given by members of management teams to leadership and inclusive leadership as enabling elements of inclusive practices. In addition, identify actions and strategies implemented in and with educational communities that are conducive to an inclusive culture.

METHODOLOGY

Methodological approach. A research with a qualitative approach is presented, with a descriptive research objective and which design corresponds to a case study, specifically for two educational establishments in the Coquimbo region, Chile.

In coherence with the qualitative approach, this study is based on the Interpretive Paradigm, which has as its premise the need to understand the meaning of social action in the context of the world life and from the perspective of the participants (Vasilachis, 1992).

Participants. The cases correspond to two public establishments in the Coquimbo region, Chile, selected by considering the following criteria:

They have a long school career (more than 30 years old)

From their Institutional Educational Projects (PEI) they declare the implementation of equal opportunities in accessibility and permanence of the school population, especially of the students who have learning difficulties, and the promotion of the integral development for all their students.

They have multidisciplinary teams and a School Integration Program focused on achieving learning for all students.

Considering the whole management team and not only the School Principal, is a decision based on the idea that leadership is a broader function than the work carried out by the Principal and is shared with other people of the institution (Ministry of Education, 2015).

In this way, the study participants were intentionally selected based on their relevance to the topic and objectives of the research. They were considered key informants as they had the possibility, disposition and interest to refer to their experience and make known the meanings of the concepts that guide the investigation. Additionally, the sample was made up of members of the management teams from each educational establishments, whose role allowed them to have a vast knowledge of the operation of the center, from an educational, administrative and organizational point of view. Through this, each establishment had four people who held the following positions:

Principal

Head of Pedagogical Technical Unit (PTU)

Head of School Coexistence

Coordinator of the School Integration Program (SIP)

These informants must also meet the requirement of having carried out functions for a minimum period of one school year, and not be acting as a substitute, because there was a risk that the informant would be unaware of certain processes and actions developed by the owner of the position.

Data collection techniques. Individual in-depth interviews carried out with each of the study participants, with the aim of offering a contextualization of the research, and knowing their perceptions and meanings in relation to the object of study. These interviews had a predefined script which function was to guide the topics to be developed, although, to investigate other content that may be serious for research, a possibility was left open.

Data analysis procedure. The general process of qualitative data analysis proposed by Rodríguez, Gil and García (1999) was carried out, performing three fundamental actions: data reduction; disposition and transformation of data, and obtaining and verification of conclusions. The encoding of the data was inductive, emerging codes during data collection. Therefore, they are better empirically based, as they are the consequence of openness to what the investigated environment has to say, instead of being limited to fit into preexisting codes (Miles, Huberman & Saldaña, 2014).

Study limitations. With the aim of triangulating the information gathered, it was initially proposed that a discussion group be held in each of the centers. However, in both cases they apologized for not doing this due to time reasons.

On the other hand, due to its qualitative approach and the focus of only two cases, on each one a purposed sample was considered limited to four subjects chosen by their relevance, it is not possible to ensure the transferability of the study results to other contexts with similar characteristics. Finally, it is important to mention that although the methodology allows achieving the stated objectives, the findings and results of this study will be searching with a higher level of depth and detail in future research.

Ethical aspects: This study was developed in the context of a postgraduate thesis from the Santo Tomás university (Chile), being approved by the Institution's Ethics Committee. Likewise, the participants agreed to participate voluntarily, carrying out an informed consent procedure with them, consisting of making the objectives and characteristics of the study known, subsequently signing an informed consent document, which confidentiality was made explicit of the information and the absence of risks for the interviewees.

RESULTS

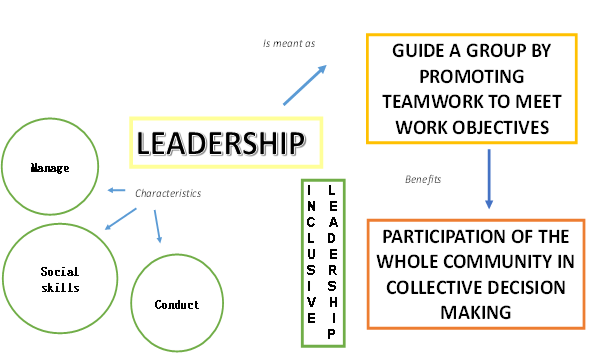

Although, the participants of the study perform different roles within the management teams, they handle a similar concept of leadership. Associating this concept to the deployment of social skills by the leader to allow them to guide a group, encourage team work, and, in consequence, achieve the objectives set by the center. Likewise, an association between leadership and the position performed is evident. Leadership is not seen as a competence that can be evidenced apart from the formal position within an organization.

"Leadership is managing, leading a group, and to be effective, the positive social skills of the educational community must be considered "(E6).

“A leader is a necessary guide that leads the team to fulfill its goals, which have been proposed” (E2).

“A leader must always be the apex of an organization, since, in a human group, a guide is always necessary to guide and orient them” (E1).

“The principal is the main figure of leadership in a school, all processes go through him” (E8).

In relation to the concept of inclusive leadership, participants distinguish similarities and differences when compared to the traditional concept of leadership. It is possible to visualize the incorporation of shared decision-making, which distances it from the generic concept of leadership where decision-making is considered as a unilateral function.

“Inclusive leadership involves the participation of the entire educational community in decision- making collectively”(E4).

“If we talk about inclusive leadership, then the decisions cannot be made by one, we must all participate” (E5).

According to this, the exercise of an inclusive leadership implies that decisions be shared, allowing appreciate the views of all people, accepting their strengths and weaknesses. As a requirement, it is necessary to develop skills and values such as: responsibility, commitment, tolerance, solidarity and empathy, on people who are part of the educational community.

"I visualize that people's minds open up and we think that we can do it and that is already positive unlike in previous years" (E5).

“If we aim to be an inclusive school, we should start by reviewing ourselves in terms of our responsibility, tolerance... how empathetic and caring we are" (E6).

"Inclusive leadership requires that school members develop certain skills and values that allow them to participate fully in decisions" (E3).

At figure 1, it is appreciated how members of management teams associate the concept of leadership with terms such as management, social skills and team leadership.This shows that the concept of leadership is understood not only as a developed skill or competence, but also as the ability to mobilize resources and people as long as the objectives set are clear. Related to this, the concept of inclusive leadership provides the variant of shared decision-making, through the participation of the entire educational community.

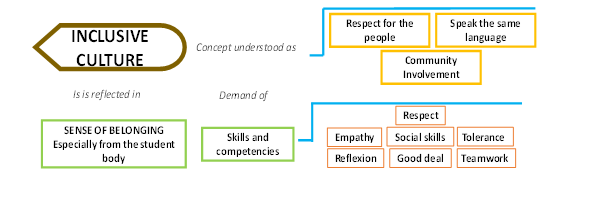

The inclusive leadership as a concept which exercise requires the active participation of the members of the educational establishments, implies the concept of inclusive culture, understood by the participants of this study as a necessary support, where all the community speaks the same language, and above all, people are respected in their differences.

"I understand inclusive culture as a base, a support, a space where we all understand each other and speak the same language, we are able to understand each other" (E2).

" there the person is really valued, there and or I accept that you are different, but with your conditions and you accept me but with my conditions, at a level of respect" (E7).

Therefore, the development of an inclusive culture requires the implementation of a set of skills and values that are specific to the community and from here its members can identify themselves. Among these, the participants mention respect for people, empathy, tolerance, teamwork, and - from a pedagogical point of view - the knowledge and application of various teaching methodologies that consider the individual characteristics of the student body.

" We must have a seal, being inclusive must lead us to identify ourselves with values or qualities such as respect, empathy, tolerance, above all ... working together" (E6).

"Being inclusive, in addition to our attitude, is expressed in the possibility of bringing to the classroom a diversity of ideas, forms, methodologies that realize that each boy is different" (E4).

There is another distinctive aspect of an inclusive culture, which is the sense of belonging of its members. According to the perception of the participants in this study, it becomes especially sensitive and relevant for students, who identify with their school and have developed affective ties with the educational community. Figure 2 visualizes the characteristic elements of an inclusive culture from the perspective of the study subjects.

" there are children who have moved to a new house and want to stay in school, I mean, they feel included in their school , they feel welcomed" (E1).

" here it’s like their second home, there are children who are, I don't know, they go out at 3 pm and are there until five, six, they don't want to go home and it happened several times. They love their school a lot. I think that the sense of belonging is very strong, too strong. In fact, when you come to the school acts they sing the anthem, and you feel that is with emotion to his school" (E3).

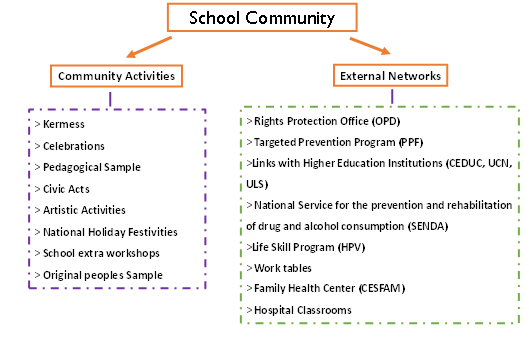

Establishing an inclusive culture that generates a sense of belonging is not only evident in the discourse of its members, but above all in the activities and initiatives that are carried out and generate participation. Besides, the participants of this study value the different activities that are carried out in and with the educational community, as well as those that arise as the own initiative of the establishment as those that are developed from external networks (See Figure 3). However, despite the fact that there is an agreement on the need to get involved in these types of activities, the participants make reference to the fact that the problems of the working environment make it difficult to carry out these initiatives, and when they are overcome, is the only way that motivation arises again for people to get involved in them.

“The activities we carry out together, all together, are like our meeting space, where we forget school meetings, sharing with parents and with everyone who sometimes we do not interact much eachother" (E6).

" because this school is in greater conflict, work environment, work, it was very bad, so this year it improved and we dared with the kermés and we repeated it, because we realized that there was a massive participation of all. As they agreed on how they cooperated, the climate was very favorable, and there was joy, massive participation” (E1).

In this sense, the range of activities developed is wide, from extracurricular academies to initiatives that involve the family and the entire school community. The participation of the different actors, both in the management of the idea and in execution, is the common denominator.

" the parent center with the directives generate their own activities. They make a work plan in March and then they decide what they want to do as a directive" (E2).

"There are several programs that come from outside. For example, from the ministry, and that takes place here... the university and other institutions also come. We welcome everyone. We always rescue the positive. I think there is always something they can contribute" (E1).

" “ The anniversary is an expected date, mainly by the students, and thus also by the parents. It is the instance where they participate, having a good time and becoming a bit like children" (E3).

DISCUSSION

The definition of leadership expressed by the study participants contains the basic elements that can be found in leadership definitions referred to in the literature. If we take as reference the definition proposed by Leithwood et al. (2006) who understands leadership as the work of mobilizing and influencing others to articulate and achieve shared goals and objectives, the notion of influence and the achievement of goals can be seen implicitly in the narratives of the subjects. However, the concept of "guiding" takes special attention, since it implies the notion of "directing" the other and not necessarily this other assumes its leading role and responsibility. Plus, it hints that the concept of leadership operates rather from a traditional conception, which links the hierarchy of a subject associated with a formal position within the organizational structure.

In particular, the concept of inclusive leadership coincides with the definition proposed by Ryan (2006), who points out that in ideal situations of inclusive leadership, all individuals, groups or representatives actively participate in policy design, decision-making, and others processes that imply influence or power and that aim to involve all people in the offer of schools and communities. Participants in this study value the importance of participation in joint decision-making and it is possible to visualize that the concept of inclusive leadership is valued and positively assumed as an irrefutable truth.

However, this conceptualization is limited as there are no references regarding how to carry it out in practice or even how to proceed with the complex issue of collective decision-making. This, may have its explanation on a strong root of the traditional idea of leadership indicated above, and not consider it as a capacity or competence that the different members of the educational community may have in the specific role they develop.

On the other hand, the members of the management teams define themselves as democratic leaders, while, at least in their intentions, they promote the team's involvement in decision-making. This style would favor the exercise of inclusive leadership, since, following González's (2008) approaches, the schools that achieve inclusion use a democratic and participative leadership approach.

Associated with this, Iglesias (2009) states that good coordination distributes tasks in such a way that each person performs his or her role appropriately. Plus, always in relation to the tasks of others, assuming his or her own responsibility and moving towards achieving a common and shared object. Though, it is possible to observe a scarce articulation or communication within the management teams, which is manifested in the limited knowledge of the functions exercised by the other team members. This could restrict the claims of establishing inclusive leadership. At the same time, participation requires a minimum level of knowledge of the subjects and their role, and of the processes that take place within the establishments, which is why coordination processes are the key.

These problems could be increased or sustained over time by the emergence of negative situations of the work environment, referred by some participants, as obstacles to the implementation of actions and initiatives that promote participation. Therefore, it is imperative to recognize this barrier, because a close relation has been found between climate and job performance (Torres and Zegarra, 2015), but also a positive work climate allows "creating the conditions for schools to be capable of initiating and sustaining processes of educational improvement and innovation to transfer the inclusive education from the Olympus to the reality of classrooms" (Echeita, 2017, p. 3).

The concept of inclusive culture deserves special attention, since a positive response to diversity depends on an inclusive culture and values that promote inclusive policies and practices, which will lead to improvements in educational centers (Gutiérrez, Martín and Jenaro, 2018). Along these lines, the participants in this study characterize and define an inclusive culture as "the participation of the entire community, where the same language is spoken and everyone is respected." When analyzing this definition, it would seem in the first instance that the expression "speaking the same language" is contradictory to the premises of the inclusive approach, because it understands inclusive culture as the acceptance of differences and not necessarily the equality of characteristics or terms. But possibly this expression refers rather to clarity in the approach of objectives and consensus on the actions to be developed.

Associated to inclusive values, it is assumed what was said by Booth and Ainscow (2015), for those, the change in schools becomes an inclusive improvement when it is based on inclusive values capable of permeating school practices and actions. Coinciding with this approach, in the context of this study, respect appears as a base value in the objective of inclusion and therefore of inclusive leadership, along with other concepts such as good treatment, tolerance and empathy.

Along these lines, Murillo, Krichesky, Castro and Hernández (2010) argue that in heterogeneous schools, planning to generate an inclusive culture helps to forge values, beliefs and activities that contribute to achieving a school for everyone, with everyone and for everyone, an aspect considered in the Institutional Educational Projects (PEI) which have a seal of " formation in values" such as: respect, perseverance and discipline. Despite of these values are declared in the PEI; it is clear that the absence of guidelines and strategies that make it possible to materialize a value framework in the actions to be carried out in and with the student body and the community in general is evident.

This value framework, seal of an inclusive culture, represents for the participants of this study the point from which the members of the educational community, especially the students, manage to identify themselves with the center and generate a sense of relevance to it. That is to say, the feeling of belonging to a group, feeling appreciated and valued in their individuality, all characteristic elements of an inclusive culture. Through this way, taking as a reference the Marco Para La Buena Dirección (Ministry of Education, 2015), this sense of belonging is emphasized, associating it with the need for students to feel represented in different ways, such as: learning path, culture, orientation of gender, age, learning style, interests, talents, etc.

An inclusive culture is promoted and materialized in concrete inclusive practices that generate the active participation of the entire community. As expressed by Echeita and Navarro (2014), to achieve a more inclusive education, it is necessary to move towards schools which are open to the participation of all: teachers, students, family, volunteers and the community in general. About this, the management teams have advanced towards a paradigmatic change, by the implementation of Law 20.845, promoting a set of activities in and from the community and with the external institutions that make up its network. This has allowed a genuine advance towards the participation of the entire community, especially the incorporation of families who cooperate at the centers. Also, it has strengthened ties between its members and has had a positive impact on terms of the organizational climate.

Many actions carried out by these centers are in line with the inclusive practices that can be found in the literature (Leiva, Gairín and Guerra, 2019; Murillo, Krichesky, Castro and Hernández, 2010; Ryan, 2016; Valdés and Gómez, 2019). However, a broader and more strategic view of managers is pending through inclusive practices, especially in two aspects. Firstly, the development of professional capacities in teachers, allowing them to advance in the conviction that the ability of all students to learn can change and be changed as a result of what they can do in the present (Hart, Dixon, Drummond and McIntyre, 2010).

Secondly, the consolidation of contexts that facilitate the linking of inclusive values and actions with the teaching-learning processes. To finish, considering the approaches of Padrón and Granados (2018), the potential offered by pedagogy should be used, as a theory that directs and enriches itself with educational practice. Also, it faces and transcends its own limitations, by searching for new styles of teaching and education in the process of socio-educational inclusion of children, adolescents and young people with different capacities and characteristics.

CONCLUSION

Leadership concept from which managers operate is strongly rooted in the traditional idea of the concept which links it rather to a hierarchical and formal position within the organizational structure and not as a capacity independent of that position. On the other hand, although inclusive leadership is highly valued and considered relevant in the pretense of being and operating as inclusive schools. The basic concept of it is managed, attributing community participation in decision-making as an almost exclusive characteristic, without references about how to carry it out in practice, not even how to proceed in the face of the complexity of collective decision-making.

At this time, considering the key role of management teams at the exercise and consolidation of inclusion in schools, limited knowledge of inclusion and current legislation was revealed. This limits the possibilities of establishing a inclusive leadership as the basis of improvement processes aimed at strengthening the participation of the educational community and the establishment of inclusive cultures.

Indeed, it is possible to show progress towards the generation of actions from the community and with external networks, where the participation of all members of the educational community is promoted. Although, it seems that these actions are only a first step in a reflection -a much broader and deeper action-, where inclusion has a holistic and strategic perspective and is inserted by an institutional development with a high level of planning, sustainable and capable of overcoming the complex and changing conditions of the environment

REFERENCIAS BIBLIOGRÁFICAS

Ainscow, M, Dyson, A., West, M. y Goldrick, S. (2013). Promoviendo la equidad en la escuela. Revista de Investigación Educativa. Número monográfico, 11(3), 44-56. [ Links ]

Ainscow, M. y Howes, A. (2006). Leading developments in practice: barriers and possibilities. En M. Ainscow y M. West (eds.), Improving Urban Schools: Leadership and Collaboration (pp. 35-45). Maidenhead: Open University Press. [ Links ]

Booth, T. y Ainscow, M. (2000). Guía para la evaluación y mejora de la educación inclusiva. Index for inclusion. Madrid: Consorcio Universitario para la Educación Inclusiva. [ Links ]

Booth, T. y Ainscow, M. (2015). Guía para la Educación Inclusiva. Desarrollando el aprendizaje y la participación en los centros escolares . Adaptación de la 3ª edición revisada del Index for Inclusion. España: OEI. [ Links ]

Echeita, G. y Navarro, D. (2014). Educación Inclusiva y desarrollo sostenible: una llamada urgente a pensarlas juntas. Edetania: estudios y propuestas socio-educativas, 46, 141-162. [ Links ]

Echeita, G. (2017). Educación Inclusiva. Sonrisas y lágrimas. Aula Abierta, 46,17-24 [ Links ]

Gómez, I. (2012). Dirección Escolar y Atención a la Diversidad: Rutas para el desarrollo de una escuela para todos. Huelva: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Huelva. [ Links ]

González, M. T. (2008). Diversidad e Inclusión educativa: algunas reflexiones sobre el liderazgo en el centro escolar. REICE. Revista Iberoamericana sobre Calidad, Eficacia y Cambio en Educación, 6(2), 82-99. [ Links ]

Gutiérrez, M., Martín, V., y Jenaro, C. (2018). La cultura, pieza clave para avanzar en la inclusión en los centros educativos. Revista de Educación Inclusiva, 11(2), 13-26. Recuperado de http://www.revistaeducacioninclusiva.es/index.php/REI/article/viewFile/325/355 [ Links ]

Hart, S., Dixon, Ab, Drummond, M.J., y McIntyre, D. (2010). Learning without limits. Maidenhead: Open University Press [ Links ]

Iglesias, A. (2009). Planificación y organización en la educación inclusiva. En M. Sarto y M. Venegas (Coords). Aspectos clave de la Educación Inclusiva, (pp. 69-84). Salamanca: Publicaciones del INICO Colección Investigación [ Links ]

Leithwood, K., Day, C., Sammons, P., Harris, A., y Hopkins, D. (2006). Successful School Leadership. What it is and how it influences pupil learning. UK: National College for School Leadership. [ Links ]

Leithwood, K. y Day, C. (2008). The impact of school leadership on pupil outcomes. School Leadership y Management, 28(1), 1-4. [ Links ]

Leiva, M., Gairín J. ,Guerra, S. (2019). Prácticas de liderazgo de los directores noveles para la inclusión educativa. Aula abierta, 48(3), 291-300. https://doi.org/10.17811/rifie.48.3.2019.291-300 [ Links ]

León-Guerrero, M. J. (2012). El Liderazgo para y en la Escuela Inclusiva. Educatio Siglo XXI, 30(1), pp. 133-160. [ Links ]

Ministerio de Educación (2015). Marco para la Buena Dirección y el Liderazgo Escolar. Recuperado de http://liderazgoescolar.mineduc.cl/wp-content/uploads/sites/55/2016/04/MBDLE_2015.pdf. [ Links ]

Murillo, F. J., Krichesky, G., Castro, A. M. y Hernández, R. (2010). Liderazgo para la inclusión escolar y la justicia social. Aportaciones de la investigación. Revista Latinoamericana de Educación Inclusiva, 10(1), 169-186. [ Links ]

Padrón, R., y Granados, L. A. (2018). Retos de la pedagogía ante la inclusión socioeducativa de niños, adolescentes y jóvenes con discapacidades. Revista Boletín Redipe, 7(12), 93-105. Recuperado de https://revista.redipe.org/index.php/1/article/view/649 [ Links ]

Rojas, M., Salas, N., Falabella, A., y Guerrero, P. (2018). Diversidad e inclusión escolar: ¿Cómo liderar los nuevos desafíos de país?. Con Dirección, cuadernos para el desarrollo del liderazgo educativo, N°9. Centro de Desarrollo de Liderazgo Educativo. Recuperado de http://cedle.cl/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Cuaderno-9-Diversidad-e-Inclusi%C3%B3n-social-vf.pdf [ Links ]

Ryan, J. (2006). Inclusive Leadership and Social Justice for Schools. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 5, 3-17. [ Links ]

Ryan, J. (2016). Un liderazgo inclusivo para las escuelas. En J. Weinstein (Ed.), Liderazgo educativo en la escuela: nueve miradas, (pp. 177-204). Chile: Ediciones Universidad Diego Portales. [ Links ]

Rodríguez, G., Gil, J., y García, E. (1999). Metodología de la investigación cualitativa. Málaga: Aljibe. [ Links ]

Sarto, M., Venegas, M. (2009). Aspectos clave de la Educación Inclusiva. Salamanca: Publicaciones del INICO Colección Investigación [ Links ]

Valdés, R. y Gómez, I. (2019). Competencias y prácticas de liderazgo escolar para la inclusión y la justicia social. Perspectiva Educacional, 58(2), 47-68. https://dx.doi.org/10.4151/07189729-vol.58-iss.2-art.915 [ Links ]

Valenciano, G. (2009). Construyendo un concepto de educación inclusiva: una experiencia compartida. En M. Sarto y M. Venegas (Coords). Aspectos clave de la Educación Inclusiva, (pp. 13-24). Salamanca: Publicaciones del INICO Colección Investigación [ Links ]

Vasilachis, I. (1992) Métodos Cualitativos I. Los problemas teórico-epistemológicos. Buenos Aires: Centro Editor de América Latina. [ Links ]

Received: November 15, 2019; Accepted: April 05, 2020

text in

text in