Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Comuni@cción

versión impresa ISSN 2219-7168

Comuni@cción vol.11 no.2 Puno jul-dic 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.33595/2226-1478.11.2.441

Original article

Between anomy and inhumanity: Femicide cases in the Puno region - Peru

1Universidad Nacional del Altiplano, Puno, Perú.

Violence against women is a problem that obeys patriarchal and macho hierarchical structures that are socially and culturally reproduced from generation to generation in the Puno region. The objectives of the study are focused on analyzing and explaining conditioning factors of the phenomenon of feminicide, as well as the motivations and beliefs that lead to committing the act of feminicide. The study method is quantitative in nature. The binary logistic regression model was used to estimate the probability of occurrence of the phenomenon, the empirical information was recovered from the MIDIS-CEM database and existing documentary analysis. The results found allow us to sustain that the cases of femicides that occur in our environment are related to the sociocultural construction of violence, motivated by individual, sociodemographic and structural factors, as well as the belief in the use of this violence as a resource for male control and domination. In addition, it is closely linked to the progress of women in the field of education and employment.

Keywords Beliefs; consequences; social context; feminicide; conditioning factors and life

Introduction

The act of femicide is currently disseminated by television, writing media and research that has been carried out on this topic in the academy, at the level of scientific articles, pre- and graduate thesis. In this regard the authors such as (Berger and Luckman, 1986) argue that the phenomenon of femicide is associated with factors of mental disorders, situations of the social context, family history with violent structures, consumption of alcohol or other drugs, etc. In Peru, figures on violence and femicide often circulate in academia and the media, however their background analysis has been poorly explored (MIMP, 2011; 2019). Already in many countries of the world femicide is considered a public health problem and public policies aimed at the prevention and care of victims of violence are being designed (Tejeda, 2014). Quantitative studies (Patró y Limiñana, 2005) as qualitative (Hardesty, Campbell and McFarlane, 2008) argue that children and their caregivers handle numerous health and adaptation challenges in the context of ongoing difficulties, resource-poor environments, and ongoing efforts to accept the loss of their loved one and its effects on their family. In addition, violence in general, and especially towards women, not only causes short- and long-term physical and mental health damage (Bonomi et al., 2006) it also affects to their sons and daughters in a family environment.

As for, McFarlane, Campbell and Watson (2001) referring to the use of the justice system before femicide of an intimate partner, found that:

The most frequent use of justice services among femicide victims attempted or consummated was to denounce the perpetrator or stalking. Among abused control officers, the most frequent use of justice services was to inform police of intellectual property assaults. African-American victims of tried or consummated femicide were the highest users of justice services, followed by white women and Hispanics. It would appear that more than half of abused women seek justice services before an attempt at femicide or consummated femicide. Thus, justice services provide a unique opportunity to connect abused women in grave danger with essential community resources that can potentially disrupt violence and prevent attempt or consummated femicide (p. 193).

The issue of femicide implies a multidimensional and multicausal view. Authors like (Taylorand Jasinski, 2011; Hernandez et al., 2016), argue that, is a phenomenon little studied empirically, both in Latin American countries and in Peru particularly, both due to its complexity and multidimensionality. There are few studies about femicide in Peru, most of them are statistical reports of the entities commissioned by the State (Villanueva, 2009; Viviano, 2010), they emphasize a legal treatment (Dador, 2012; Estrada, 2011 ), have studied judicial records of femicide and attempted femicide and have tried to deepen the methodological problems to study it (Mujica and Tuesta, 2012).

For (Monárrez, 2002) femicide implies the total subordination and appropriation of the woman's body by men just because they are a woman. Along the same lines, authors such as (Radford, 1992; Taylor and Jasinski, 2011; Wilson and Daly, 1992) have defined femicide as that which explains the position of women by a system that subordinates them in a totalizing way. Hence, according to studies, femicide presents similar characteristics such as jealousy, sense of ownership, violent response to infidelity or end of relationship, etc. (Ellis and Dekeseredy, 1998; Lagarde, 2008). On the other hand, studies such as (Shalhoub-Kervorkian and Daher-Nashif, 2013; Fulo Y Miedema, 2015) argue that since there is no theoretical independence, opinions in favor of having objectively relevant explanatory frameworks have not diminished, which helped decolonialize the cultural approach to femicides and integrate them into causes linked to the processes of globalization and world system. Studies on cases of women who "kill" their partners are much less frequent in Peru, as well as in the world (Heise and García-Moreno, 2002). This reality is also common in other countries (Taylo and Jasinski, 2011). Such differences make us stop asking ourselves why some kill others and, instead, we must answer why a certain group (men) murders another (women) (Monárrez, 2002).

Theoretical framework

Femicide is a problem that must be addressed as the most extreme and inhumane form of direct violence against women. It is a social, economic, political, cultural and state problem. "Femicide has been treated from different perspectives and disciplines, such as psychology, sociology and feminist political theory" (Saccomano, 2017 p. 56). Violence against women is not exclusive to any country; it occurs in all societies in the world and without distinction of economic position, race or culture. In Latin America, the causes of femicide are related to structural and sociocultural violence that is reproduced in different areas and sectors of society (Lagarde, 2008; Carcedo, 2000 and Toledo, 2009) they explained. In the same perspective, another group of researchers associate the causal factors of violence against women and femicide with individual and socio-structural variables (Heise, 1998; Krug, Etienne, Dahlberg, Linda, Mercy, Zwi, and Lozano, 2000) and for his part Gómez (2008) considers femicide as a public health problem. For (Bourdieu, 2000) the social order works as an immense symbolic machine that tends to ratify male domination supported by the sexual division of labor.

Feminist approach to Femicide

The feminist streams in Latin America claims that the main reason of the cases of feminicides are associated with structural gender inequality and the impunity of the perpetrators in the justice system, the theory places crimes against girls and women in the patriarchy and considers them the extreme of gender domination against women (Lagarde, 2008). Lagarde (2000) maintains: “Femicide is genocide against women and it happens when historical conditions generate social practices that allow violent attacks against the integrity, health, freedoms and lives of girls and women” (p. 216).

Feminist approaches agree when relating cases of feminicide with sociocultural and political factors, so that violence against women is the product of a structural system (Carcedo, 2000). In the same perspective (Chow and Berheide, 1994) argue that societies in the world are characterized by gender inequality, which has its roots in the sexual division of labor and is perpetuated by the process of gender socialization. In the ideas of Sagot (1994) in a patriarchal society, the transmission of the ideology of oppression is the main element of socialization.

Ecological approach to Femicide

In this position, acts of feminicide are attributed to the individual characteristics of the woman (such as having witnessed violence in the home, having been a victim of violence and having had an absent father), at the microsystem level (such as male domination in the family, the control of money on the part of the man, the consumption of alcohol and marital and verbal conflicts) and the level of exosystem (such as unemployment, low socioeconomic level and friends of the criminal world in the man). The ecological approach to abuse conceptualizes violence as a multifaceted phenomenon based on an interaction between personal, situational, and sociocultural factors (Heise, 1998; Krug, et al., 2002) and femicide in general. The authors point out the complexity of the factors related to violence against women:

Violence is the result of the complex interaction of individual, relational, social, cultural and environmental factors. Understanding how these factors are related to violence is one of the important steps in the public health approach to preventing violence (Krug et al., 2002, p. 12).

Violence has long-term consequences for these women and their children, as well as social and economic costs for the whole of society, as WHO (2012) argues:

Femicide committed by someone without an intimate relationship with the victim is known as non-intimate femicide, and femicide that involves sexual assault is sometimes referred to as sexual femicide. Such killings may be random, but there are disturbing examples of systematic killings of women, particularly in Latin America (p. 4).

The comprehensive and multidimensional approach used by the ecological model is confirmed by scientific research on mortality in the field of public health. Gómez (2008) affirms that "violent deaths by homicide are avoidable, as evidenced by industrialized countries where homicides have notably decreased through preventive public policies aimed at reducing social inequalities through control of social, cultural and economic determinants" (p. 83)

Political-legal approach to Femicide

According to CEDAW (1992) The General Recommendation No. 19 of 1992 was historic, since it clearly framed violence against women as a form and manifestation of discrimination based on gender, used to subordinate and oppress women. Without a doubt, it brought the violence out of the private sphere into the sphere of human rights; General Recommendation No. 35 is also a milestone:

Recognizes that the prohibition of gender-based violence has become a norm of customary international law; It broadens the understanding of violence to include violations of sexual and reproductive health rights; Stresses the need to change social norms and stereotypes that support violence, in the context of a resurgence of narratives that threaten the concept of gender equality in the name of culture, tradition or religion (CEDAW, 1992, p. 2).

The 1993 World Conference on Human Rights was considered a success by feminist activists, broadening the international human rights agenda to include gender-specific violations, some of which were identified as human rights violations (Sullivan, 1994, p. 152). Since 1994, the Convention of Belém do Pará was adopted, which clearly establishes that “violence against women is an offense to human dignity and a manifestation of historically unequal power relations between women and men”, and reiterated that every woman has the right to live without violence and any form of discrimination. (OAS, 1994; art. 6). Since the adoption of the Convention of Belém do Pará, the Latin American countries have entered a process of convergence and the gender perspective was included in both into public policies in general and national legislation (Galanti and Borzacchiello, 2013).

According to a study conducted by Carcedo (2000) indicates that “the regulation of a crime should provide a legal instrument that allows women to access protection and request help from the authorities when they are subjected to violence” (p. 72). At that regard Saccomano (2017), concludes:

It is found that the criminalization (or typification) of femicide is not significant to predict the rate of femicide; On the other hand, low levels of the rule of law and the lack of representation of women in decision-making bodies, such as national parliaments, appear as the most relevant factors to explain the variation in trends in femicides (p.51)

Materials and method

This information comes from the database of the Women's Emergency Center (CEM-Puno, memorias anuales del MEM - MIMP, Defensoría del Pueblo periodo del 2015 - 2019), SSPS v. 22 Statistical Software was used for the processing of information. The research is quantitative in nature and the binary logistic regression tests for the analysis and treatment of data (Hernández et al., 2015). Following the above procedures is aimed to achieve the expected results in the objectives set.Consequently, we start from the equation, where the dependent variable maintains a multilinear relationship with the vector X or predictor variables.

𝑌 = 𝛽0 + 𝛽1. 𝑋ij + 𝜀ij

Where Y is the dependent variable that takes 1 if the woman was a victim of violence with a femicide outcome and 0 attempted femicide. X it is a vector that collects the risk factors for femicide by determining factors; 𝜀 is the error term. For the case study, a convenience sample (140 cases) has been used, taking into account one hundred percent of cases registered in the MIMP unit - Women's Emergency Center at the Puno Region level, in the last 5 years. Consequently, the dimensions of analysis have been the individual, sociodemographic and structural factors associated with acts of femicide.

Results and discussion

For Monárrez (2002), analyzed from the social and symbolic point of view, femicide has connotations of subordination and the appropriation of the woman's body by men, due to the fact of being a woman. Subordination has not only made violence socially accepted but it has been embedded in social institutions, at the same time that they have reproduced it (Taylor and Jasinski, 2011).

Magnitude of the cases of attempted and femicide in the country

Femicide cases in the country

According to the country's literature, the first data recorded show that most of them are perpetrated by couples, ex-partners or close relatives. According to Centro de la Mujer Peruana Flora Tristán points out that "more than 64% of the victims at the time of the attack had a sentimental, affective or intimate relationship with their aggressor" (Citado en Defensoría del Pueblo, 2010)

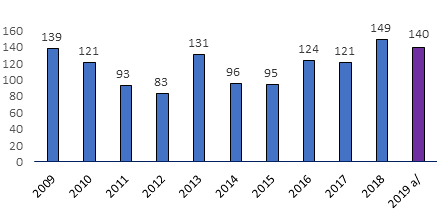

There are few studies on femicide-related factors in Peru, most of which are reports of statistics and specific measures or proposals (Villanueva, 2009; Viviano, 2010) and have a legal approach (Dador, 2012; Estrada, 2011). The largest cases of femicide in the country are in the regions such as: Metropolitan Lima, Arequipa, Callao, Cusco, Huánuco, La Libertad and Puno are the regions (see Chart 01). According to (MIMP-CEM, 2019), the evolution of femicide cases in the country are quantitatively high between 2009 and 2019, among those years 1292 women of different ages and social status have lost their lives.

Table 1 Cases of femicide victims by area of occurrence

| Area | 2019 a / | 2018 | ||

| No. | % | No. | % | |

| Urban | 90 | 64% | 76 | 51% |

| Rural | 44 | 31% | 31 | twenty-one% |

| Marginal urban | 6 | 4% | 19 | 13% |

| It is unknown | 0 | 0% | 2. 3 | fifteen% |

| Total | 140 | 100% | 149 | 100% |

a / Cases of victims of femicide that occurred as of October 31, 2019

Source: Data registered by the CEM in the country 2019

When the phenomenon is analyzed according to the urban and rural context, the highest percentage of cases occur in the urban area with 64%, while in rural area it represents 31% and a percentage less than 4% in the marginal urban area (see table 1). Now, considering data from the registry of (MIMP-CEM, 2019) that counts people who are victims of femicide and attempts, it is noted that a use of violence with a strong gender bias (men towards women) prevails in the country. The modality of cases of victims of femicide, the highest percentage is by stabbing (23%), followed by asphyxia / strangulation (29%) and the modality by bullet shots represents (15%) respectively (see table 2).

Table 2 Modality of the case of the victim of femicide

| Modality | Femicide | |

|---|---|---|

| No. | % | |

| Stabbing | 32 | 23% |

| Various blows | 16 | 11% |

| Bullet shot | 21 | 15% |

| Poisoning | 5 | 4% |

| Unraveling | 0 | 0% |

| Choking / strangulation | 41 | 29% |

| Run over | 1 | 1% |

| Burn | 4 | 3% |

| Other | 20 | 14% |

| Total | 140 | 100% |

Source: Data registered by the CEM in the country 2019

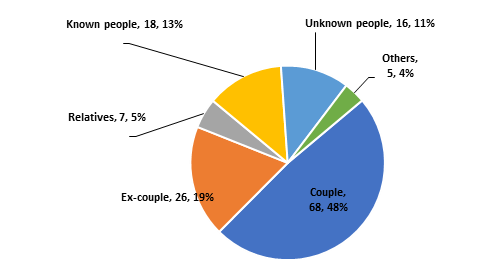

Another aspect to consider is the scarcity of accurate data on the conditioning factors of femicide in the country and in the Puno region. National statistics do not record the motive, nor the different types of violence that women suffered before being murdered. However, the data is available according to the relationship that the victim had with her perpetrator. Faced with such a situation, it is necessary to specify that 68.48% of the cases, the aggressors (femicides) are their current partners, and 26.19% of the aggressors have been their ex-partners and 18.13% of those reported are someone known to the victim and 16.11% are people unknown to the victim (see graph 02).

Conditioning factors of femicide cases in the Puno region.

From birth, men and women participate in different socialization processes. Men are taught to adopt values, assumptions, behaviors and stereotypes that are assumed to be inherent to their sex. Likewise, within this socialization process, they are taught how to relate to other people (Tamayo, 1990; Defensoría del Pueblo, 2010). In general, the men who commit acts of feminicide in the country do not report having consumed any psychoactive substance, including alcohol or drugs, the figures are evident in this regard, 51% have not consumed alcohol or drugs at the time of committing the act of femicide, while 27% of the aggressors have been under the influence of a drug such as alcohol (see table 3).

Table 3: Femicide cases according to the aggressor's status (Alcohol / drugs)

| Alcohol / drugs | No. | % |

| Yes | 38 | 27% |

| No | 71 | 51% |

| No information | 31 | 22% |

| Total | 140 | 100% |

Source: Data registered by the CEM in the country 2019

For analysis of the factors related to the phenomenon of “feminicide”, the bivariate logistic regression model was designed, having as the dependent variable the total number of cases of the people who were victims of feminicide and the independent variables will be each of the sociodemographic variables, socioeconomic, individual.

𝑌 = 𝛽0 + 𝛽1. 𝑋ij + 𝜀ij

Table 4 Vine logistic regression "Level of education" of women who were victims of femicide in the Puno region

| Variables and categories | Odds ratio (OR) | Significance level |

|---|---|---|

| No instruction | 0.7 | *** |

| Primary | 1.2 | ** |

| High school | 2.4 | *** |

| Higher | 2.9 | *** |

Statistical significance level * p <0.05 ** p <0.01 *** p <0.001 p> 0.05

Source: own elaboration based on data from MIMP- CEM- Puno 2019

Table N ° 4 shows the risk values of being the object of violence and with subsequent femicide it increases with a higher level of education. In other words, women with a year of higher education have a 2.9 times more likely to be victims of feminicide than those with a lower level of education. Something similar happens with women who have a high school education, have 2.4 times the risk of being subjected to feminicide than those who have a primary school.

Table 5 Binary logistic regression “age” of women who were victims of femicide in the Puno region

| Variables and categories | Odds-ratio (OR) | Significance level |

|---|---|---|

| 0 to 5 years | 0.2 | *** |

| 6 to 11 years | 0.5 | ** |

| 12 to 14 years | 0.9 | *** |

| 15 to 17 years | 1.8 | ** |

| 18 to 29 years | 4.7 | *** |

| 30 to 59 years | 2.1 | *** |

| 60 years or more | 0.8 | ** |

Statistical significance level * p <0.05 ** p <0.01 *** p <0.001 p> 0.05

Source: own elaboration based on data from MIMP- CEM- Puno 2019

The values of the bivariate logistic regression model show us that younger people have a higher risk of being victims than older people. The values indicate that the 18 to 29 year old group has a 4.7 times higher risk of being victims of femicide than the 15 to 17 year old group. Another group of ages between 30 to 59 years of age also registers Odds ratio (OR) values of 2.1, which implies that women who are in this age group are 2 times more victims of femicide than those who are younger than 17 years. Similarly, women in the age group 60 years of age and older have a 0.8 times lower probability of being a victim of risk of femicide than other age groups (see table 5).

Table 6 Bivariate logistic regression “age” of the aggressors of the women victims of femicide in the Puno region

| Variables and categories | odds ratio (OR) | Significance level |

|---|---|---|

| 14 to 17 years | 0.7 | * |

| 18 to 29 years | 5.0 | *** |

| 30 to 59 years | 8.2 | *** |

| 60 years or more | 0.3 | ** |

Level of statistical significance * p <0.05 ** p <0.01 *** p <0.001 p> 0.05 not significant ns

Source: own elaboration based on data from MIMP- CEM- Puno 2019

The values of the bivariate logistic regression model, it can be observed that relatively young men have a greater probability of committing the act of feminicide towards a woman. The values indicate that the age group from 30 to 59 years old is 8.2 times more likely to commit the act of feminicide, while the age group from 18 to 29 years old is 5.0 times greater than the age group from 14 to 17 years old. (see table 6).

Work activity is one of the variables of equal importance for the study, table 7 shows us that as the labor insertion of women in work activities increases independently, acts also increase the risk probability of being a victim of femicide. In other words, the values indicate that women who worked independently have been victims of femicide in 2.2 times more than other occupations. In the same way, women who were engaged in domestic activity have been victims of feminicide in 1.9 times more than other occupations. Therefore, as women become independent from dependence on men by obtaining a salary, the risk of suffering as a victim of violence with the risk of femicide is high; which indicates that as women's wages increase, the risk of being a victim increases.

Table 7 Binary logistic regression "work activity" of women who were victims of femicide in the Puno region

| Variables and categories | Odds-ratio (OR) | Significance level |

|---|---|---|

| Domestic employee | 0.7 | ** |

| Informal commerce | 1.5 | ** |

| Public employee | 0.9 | *** |

| Independent worker | 2.2 | *** |

| Domestic activity | 1.9 | ** |

Statistical significance level * p <0.05 ** p <0.01 *** p <0.001 p> 0.05

Source: own elaboration based on data from MIMP- CEM- Puno 2019

The regression estimates on the individual factors of the aggressors are mostly statistically significant (p = 0.000) which indicates that if the occurrence of feminicide in women can be predicted according to the silver model. Table N ° 10 shows the values of Odds ratio (OR), the factors as the aggressor's state condition (in a sober state) at the time of the act of femicide is 3.7 times greater than the consumption of some psychoactive substance (alcohol or drug), in the same way, the factor “having been a victim of violence in childhood” is 2.1 times greater than the other factors under study. Another factor that is significantly valid is “having witnessed violence in home” showing that aggressors who have witnessed violence in home are 1.3 times more likely to commit the act of femicide (see table 8).

Table 8 Multivariate logistic regression "individual factors" of the aggressors of women victims of femicide in the Puno region

| Variables and categories | Odds-ratio (OR) | Significance level |

|---|---|---|

| Witnessing violence in the home | 1.3 | ** |

| Effects of alcohol consumption | 0.4 | ** |

| Effects of drug use | 0.0 | ns |

| Having been a victim of violence in childhood | 2.1 | *** |

| Having had an absent father | 0.5 | * |

| In a sober state | 3.7 | *** |

Level of statistical significance * p <0.05 ** p <0.01 *** p <0.001 p> 0.05 not significant ns

Source: own elaboration based on data from MIMP- CEM- Puno 2019

Men who have a formal occupation are less likely to commit acts of feminicide, however, the opposite happens with those who are inserted in occupations or informal activities, the logistic regression values - Odds ratio (OR) indicate that the probability committing increases 3 times higher in those men who have informal occupations. Next are those people (men) without occupation with a value of 2.8, which means that as the man has a stable formal job, the probability committing acts of femicide will decrease (see table 9).

Table 9 Multivariate logistic regression "structural factors" of the aggressors of women victims of femicide in the Puno region

| Variables and categories | odds ratio (OR) | Significance level |

|---|---|---|

| Idle | 2.8 | ** |

| With formal occupation | 1.1 | * |

| With informal occupation | 3.7 | *** |

| Low incomes | 0.6 | * |

| High income | 1.2 | ** |

Level of statistical significance * p <0.05 ** p <0.01 *** p <0.001 p> 0.05 not significant ns

Source: own elaboration based on data from MIMP- CEM- Puno 2019

Motivations and beliefs of the aggressors

All kind of violence against women, are always followed by a risk of femicide, so it is important to analyze the causes and consequences. Violence against women is a historical and socio-political construction. Men do not always beat their women and, if they do, the beatings do not always respond to the same reasons. Definitions of what constitutes unacceptable or acceptable physical aggression vary with changes in notions of sexual roles and the sexual division of labor, and their implications for the natural and social order (Bourdieu, 2000), with the transformation of the organization of sexuality in the family and in society (Tinsman, 1995). The motivations and beliefs of the aggressors are more frequently motivated by jealousy, infidelity and revenge respectively (see table 10).

Table 10 Supposed motives of the crime declared by the aggressors

| Reason | Total | Femicide | Attempt | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jealousy | 6 | 4 | 2 | 28.57 |

| Infidelity victim | 5 | 3 | 2 | 23.81 |

| Decides to separate | 3 | 1 | 2 | 14.29 |

| Refusal to be a couple | 2 | 2 | 0 | 9.52 |

| Revenge | 4 | 1 | 3 | 19.05 |

| Victim demands or denounces it | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Victim leaves home | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4.76 |

| Victim starts new relationship | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Total | 21 | 12 | 9 | 100% |

Source: own elaboration based on data from MIMP- CEM- Puno 2019

The model Multivariate shows the results of odds ratio (OR) similar to those described above, which includes the beliefs and motivations of men who attack women until committing femicide. The regression values indicate that jealousy and alleged infidelity of woman are triggers to commit the act of feminicide in the region. This probability is very high according to the values estimated by the logistic regression model (6.6 and 5.1 odds ratio), this means that jealous men are 6 times more likely to commit femicide compared to those who do not have that kind of feelings and 5 times greater probability of risk committing the act of femicide motivated by infidelity acts from the couple (woman). Other motivations such as a feeling of revenge, separations and refusal of a romantic relationship are also grounds for male sociodicea, to justify acts of this type (see table 11).

Table 11 Multivariate logistic regression "motivations and beliefs" of the aggressors of women victims of femicide in the Puno region

| Variables and categories | Odds-ratio (OR) | Significance level |

|---|---|---|

| Jealousy | 6.6 | ** |

| Victim infidelity | 5.1 | *** |

| Decide to separate | 3.2 | *** |

| Refusal to be a couple | 2.7 | *** |

| Revenge | 4.8 | *** |

| Victim demands or denounces it | 0.0 | sn |

| Victim leaves home | 1.7 | * |

| Victim starts new relationship | 0.0 | sn |

Level of statistical significance * p <0.05 ** p <0.01 *** p <0.001 p> 0.05 not significant n.s

Source: own elaboration based on data from MIMP- CEM- Puno 2019

The harmony between objective structures and internal subjective ones, hide the historical and social conditions that made possible its realization under the veil of toxic experience. Comparing the results of the studies on the attempt and femicide, most of the authors coincide in stating that such behaviors are abnormal and associated with structural, individual, and psychosocial factors (Berger and Luckman, 1986; Bourdieu, 2000). When the causal factors are verified, some authors already mentioned above, agree that the phenomenon of feminicide has as its base history similar characteristics such as jealousy, sense of ownership, violent response to infidelity or the end of the relationship. From the theoretical point of view, femicide has not become independent from what has been formulated in relation to general violence against women (Ellis and Dekeseredy, 1998; Lagarde, 2008). On the other hand, studies such as Shalhoub-Kervorkian and Daher-Nashif (2013); Fulu and Miedema (2015) argue that in the absence of theoretical independence, opinions in favor of having objectively relevant explanatory frameworks have not diminished, which helped decolonialize the cultural approach to femicides and integrate them into causes linked to the processes of globalization and of the world system.

Conclusions

The results of estimating the regression of the binary model show us that the younger population (20 to 29 years) and women with higher levels of schooling (higher) are more likely to be victims of femicide. Similarly, women who are embedded in formal work activities and therefore receive higher incomes show an increased risk of femicide in the Puno region.

The results show that femicide cases are directly associated with individual factors as a condition of the aggressor's status, having been victim of violence in their childhood and having witnessed violence at home. As well as socioeconomic factors (occupation of women and income they receive) are conditioning factors of increased risk of occurrence of femicide in the Puno region.

Another factor that motivated the act of femicide is the jealousy and supposed infidelity of women. This probability of occurrence of the act of femicide is very high according to the values estimated by the multivariate model. Other motivations such as feeling of revenge, separations and refusal of a romantic relationship are also grounds for male justification, to commit this kind of acts.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgement

To National University of the Altiplano through the Special Fund for University Development (FEDU) which provided financial support for the execution and publication of the research results.

REFERENCES

Araujo, K., Guzman, V. & Mauro, A. (2000). El surgimiento de la violencia doméstica como problema público y objeto de políticas. Revista de la Cepal, n. 70, Santiago de Chile. [ Links ]

Berger, P, y Luckmann, T. (1986). La construcción social de la realidad. Buenos Aires, Argentina: Amorrortu [ Links ]

Bonomi, A. et al. (2006). Intimate partner violence and women's physical, mental, and social functioning. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 30(6), 458-466. [ Links ]

Bourdieu, P. (2000). La dominación masculina. Barcelona: Anagrama (La domination masculine. París: Editions deu Seuil, 1998). http://www.nomasviolenciacontramujeres.cl/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Bondiu-Pierre-la-dominacion-masculina.pdf [ Links ]

Carcedo, A. (2000). Femicidio en costa rica 1990-1999. [ Links ]

Carlson, B. (1984). Causes and maintenance of domestic violence: An ecological analysis. Social Service Review, 58(4), 570-587. [ Links ]

CEDAW-Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women. (1992). CEDAW General Recommendation n.º 19: Violence against women. CEDAW https://www.ohchr.org/en/hrbodies/cedaw/pages/gr35.aspx [ Links ]

Chow, E. & Berheide, C. (1994). Women, the Family and Policy a Global Perspective. SUNY Press. New York. Recuperado de: https://www.amazon.com/Women-Family-Policy-Perspective-Society/dp/0791417867 [ Links ]

Corradi, C., Marcuello-Servós, C., Boira, S., y Weil, S. (2016). Theories of femicide and their significance for social research. Current Sociology (2), 1-21 [ Links ]

Dador, J. (2012). Historia de un debate inacabado. La penalización del feminicidio en el Perú. Movimiento Manuela Ramos, Lima - Perú. [ Links ]

DEFENSORÍA DEL PUEBLO. (2010). Feminicidio en el Perú. Análisis de expedientes judiciales. Lima: Serie Informes de Adjuntía - Informe Nº 04-2010/DP-ADM. [ Links ]

DEFENSORÍA DEL PUEBLO. (2015). Feminicidio Íntimo en el Perú: Análisis de Expedientes Judiciales (2012 -2015). Lima. [ Links ]

Díaz, R., y Miranda, J. (2010). Aproximación del costo económico y determinantes de la violencia doméstica en el Perú. Lima: IEP, CIES. [ Links ]

Ellis, D., y Dekeseredy, W. (1998). Rethinking Estrangement, Interventions, and Intimate Femicide. Violence Against Women, 3(6), 590-609. [ Links ]

Estrada, H. (2011). El feminicidio en el Perú y en la legislación comparada. Lima: Departamento de Investigación y Documentación Parlamentaria. Congreso de la República. [ Links ]

Fulo, E. y Miedema, S. (2015). Violence Againts Women: Globalizing the integrated ecological model. Recuperado de: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280536888_Violence_Against_Women [ Links ]

Galanti, V. & Borzacchiello, E. (2013). IACrtHR’s influence on the convergence of national legislations on women’s rights: legitimation through permeability. International Journal of Social Sciences, Vol. II, Nº 1 (2013), p. 7-27. [ Links ]

Gómez, R. (2008). La mortalidad evitable como indicador de desempeño de la política sanitaria Colombia: 1985-2001. Medellín: Revista Facultad Nacional de Salud Pública, Universidad de Antioquia, 2008. [ Links ]

Hardesty, J., et al. (2008). How children and their caregivers adjuste after intimate partner femicide. Journal oa Family Issues, 29(1), 100124. [ Links ]

Heise, L. (1998). Violence Against Women: An Integrated, Ecological Framework. Violence Against Women, 4(3), 262-290. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801298004003002 [ Links ]

Heise, L., y García-Moreno, C. (2002). Violence by intimate partners. En E. Krug, L. Dahlberg, J. Mercy, A. Zwi, & R. Lozano, World report on violence and health (págs. 87-122). Geneva: Organización Mundial de la Salud. [ Links ]

Hernandez, et al., (2015). Metodología de investigación. 6ta edición MacGrawHill - México. [ Links ]

Hernández, W. (2016). Feminicidio (agregado) en el Perú y su relación con variables macrosociales. Urvio Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios de Seguridad (17), 48-66. [ Links ]

Incháustegui, T. (2014). Sociología y política del feminicidio; algunas claves interpretativas a partir de caso mexicano. En revista Sociedade e Estado, México. [ Links ]

Krug, G., Dahlberg, L., Mercy, J., Zwi, A., & Lozano, R. (2002). World report on violence and health / edited by Etienne G. Krug ... [et al.]. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42495 [ Links ]

Lagarde, M. (2008). Antropología, feminismo y política: violencia feminicida y derechos humanos de las mujeres. En M. Bullen, & C. Diez, Retos teóricos y nuevas prácticas (págs. 209-239). XI Congreso de Antropología de la FAAEE, Donostia, Ankulegi Antropologia Elkartea. [ Links ]

McFarlane, et al. (2001). The use of the justice system prior to intimate partner femicide. Criminal Justice Review, 26(2), 193-208. [ Links ]

MIMP, (2011). Estado de las investigaciones sobre violencia familiar y sexual en el Perú. Lima. Recuperado de: https://www.repositoriopncvfs.pe/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Estado-de-las-investigaciones.pdf [ Links ]

MIMP-CEM (2019). Feminicidio, https://www.mimp.gob.pe/contigo/contenidos/pncontigo-articulos.php?codigo=39 [ Links ]

Monárrez, J. (2002). Feminicidio sexual serial en Ciudad Juárez: 1993-2001. Debate Feminista, 13(25), 279-305. [ Links ]

Mujica, J., y Tuesta, D. (2012). Problemas de construcción de indicadores criminológicos y situación comparada del feminicidio en el Perú. Recuperado de: http://www.scielo.org.pe/pdf/anthro/v30n30/a09v30n30.pdf [ Links ]

OEA-Organization of American States. (1994). Convención Interamericana para prevenir, sancionar y erradicar la violencia contra la mujer “Convención de Belém do Para”. OEA, (9 de junio de 1994). https://www.oas.org/es/mesecvi/convencion.asp [ Links ]

Patró, R., y Limiñana, R. (2005). Víctimas de violencia familiar: Consecuencias psicológicas en hijos de mujeres maltratadas. Anales de Psicología, 21(1), 11-17. [ Links ]

Radford, J. (1992). Introduction. En J. Radford, & D. Russell, Femicide. The politics of woman killing (págs. 3-12). New York: Twayne Publishers. [ Links ]

Ribero, R., & Sánchez, F. (2004). Determinantes, efectos y costos de la violencia intrafamiliar en Colombia. Documento CEDES 2004-44. [ Links ]

Russell, D. (2008). Feminicide: politicizing the killing of females. En PATH, Strengthening understanding of femicide. Using researcht to galvanize action and accountability (págs. 26-31). Washington D.C. [ Links ]

Sacomano, C. (2017). El feminicidio en América Latina: ¿vacío legal o déficit del Estado de derecho? Revista CIDOB d’Afers Internacionals. n.117, p. 51-78. DOI: doi.org/10.24241/rcai.2017.117.3.51 [ Links ]

Sagot, M., (1994). “Marxismo, Interaccionismo Simbolico y la Opresión de la Mujer”. Revista de Ciencias Sociales N° 36. Universidad de Costa Rica. [ Links ]

Shalhoub-Kervorkian, N., & Daher-Nashif, S. (2013). Femicide and colonization: between the politics of exclusion and the culture of control. Violence Against Women, 19(3), 295315. [ Links ]

Sullivan, D. (1994). “Women’s Human Rights and the 1993 World Conference on Human Rights”. American Journal of International Law, vol. 88, N°. 1 (1994) p. 152-167. [ Links ]

Tamayo, G., y García, J.M. (1990). Mujer y varón. Vida cotidiana, violencia y justicia. Lima: Ediciones Raíces y Alas. [ Links ]

Taylor, R., y Jasinski, J. (2011). Feminicide and the feminist perspective. Homicide Studies, 15(4), 341-362. [ Links ]

Tejeda, D. (2014). Feminicidio: Un problema social y de salud pública. La manzana de la discordia, 9(2), 31-42. [ Links ]

Tinsman, H. (1995). Los patrones del hogar. Esposas golpeadas y control sexual en Chile rural (1958- 1998). Recuperado de: https://www.academia.edu/17623131/_Los_Patrones_del_hogar_Esposas_golpeadas_y_control_sexual_en_Chile_rural_1950-1988. [ Links ]

Toledo, P. (2009). Feminicidio. Consultoría para la Oficina en México del Alto Comisionado de las Naciones Unidas para los Derechos Humanos. Edit. OACNUDH México Recuperado de: http://www.nomasviolenciacontramujeres.cl/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/P.-Toledo-Libro-Feminicidio.compressed.pdf [ Links ]

Villanueva, R. (2009). Homicidio y feminicidio en el Perú. Septiembre 2008 - junio 2009. Lima: Observatorio de Criminalidad del Ministerio Público. [ Links ]

Viviano, T. (2010). El poder de los datos: Registro de feminicidio para enfrentar la violencia hacia la mujer en el Perú. Lima: Ministerio de la Mujer y Desarrollo Social. [ Links ]

Wilson, M., & Daly, M. (2008). Spousal conflict and uxoricide in Canada. En PATH, Strengthening understanding of femicide. Using research to galvanize action and accountability (pág. 119). Washington: PATH, MRC, WHO, Intercambio. [ Links ]

Received: August 08, 2020; Accepted: October 18, 2020

texto en

texto en