Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Revista Digital de Investigación en Docencia Universitaria

On-line version ISSN 2223-2516

Rev. Digit. Invest. Docencia Univ. vol.11 no.1 Lima Jan./Jun. 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.19083/ridu.11.497

RESEARCH ARTICLE

CLIL Teachers’ Perceptions of Intercultural Competence in Primary Education

Percepciones del profesorado AICLE sobre la competencia intercultural en Educación Primaria

Percepções dos professores AICLE sobre a competência intercultural no Ensino Básico

Elisa Pérez Gracia* (http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6219-7203)

Ma Elena Gómez Parra** (http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7870-3505)

Rocío Serrano Rodríguez*** (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9447-9336)

* Departamento de Filologías Inglesa y Alemana, Facultad de Ciencias de la Educación, Universidad de Córdoba, Córdoba, España. E-mail: m82pegre@uco.es

** Departamento de Filologías Inglesa y Alemana, Facultad de Ciencias de la Educación, Universidad de Córdoba, Córdoba, España. E-mail: elena.gomez@uco.es

*** Departamento de Educación, Facultad de Ciencias de la Educación, Universidad de Córdoba, Córdoba, España. E-mail: rocio.serrano@uco.es

ABSTRACT.

CLIL (Content and Language Integrated Learning) includes the development of intercultural awareness as one of its main axes. Therefore, the main objective of this research is to examine the perceptions that CLIL teachers have regarding Intercultural Competence (IC) and the elements that contribute to its development. Through an open-question survey, we analysed the opinions of 59 Primary Education CLIL teachers from Cordoba. For the analysis of the qualitative data, Atlas.ti has been used on its two options: the textual and the conceptual analysis, thus generating the corresponding networks. On the other hand, SPSS v. 21 was used for the quantitative data analysis. The results show that CLIL teachers define IC closely linked to linguistic competence, and that communicative activities play an important role.

Key words: CLIL, Intercultural Competence, Teachers, Education.

RESUMEN.

En el enfoque AICLE (Aprendizaje Integrado de Contenidos y Lenguas Extranjeras), el desarrollo de la conciencia intercultural adquiere un protagonismo esencial. Por ello, conocer la percepción que el profesorado AICLE tiene en relación a la Competencia Intercultural (CI) y los elementos que contribuyen a su desarrollo se convierte en el objetivo fundamental de esta investigación. Mediante un cuestionario abierto se han analizado las opiniones de 59 profesores de Córdoba que trabajan con dicho enfoque en Educación Primaria. Para el análisis de los datos cualitativos se ha usado Atlas.ti en sus dos vertientes: el análisis textual y el análisis conceptual, generando las Networks correspondientes. Por otro lado, para el análisis de datos cuantitativos se utilizó el programa SPSS v. 21. Los resultados muestran que el profesorado AICLE define la CI estrechamente vinculada a la competencia lingüística y, por lo tanto, señala que las actividades comunicativas son las que más ayudan a fomentar la CI.

Palabras clave: AICLE, Competencia Intercultural, Docentes, Educación.

RESUMO.

No enfoque AICLE (Aprendizagem Integrada de Conteúdos e Línguas Estrangeiras), o desenvolvimento da consciência intercultural adquire um protagonismo essencial. Por isso, conhecer a percepção que os professores AICLE têm com relação à Competência Intercultural (CI) e os elementos que contribuem a seu desenvolvimento torna-se o objetivo fundamental desta pesquisa. Mediante um questionário aberto foram analisadas as opiniões de 59 professores de Córdoba que trabalham com esse enfoque no Ensino Básico. Para a análise dos dados qualitativos utilizou-se o Atlas.ti em suas duas vertentes: a análise textual e a análise conceitual, gerando as Networks correspondentes. Por outro lado, para a análise de dados quantitativos utilizou-se o programa SPSS v. 21. Os resultados mostram que os professores AICLE definem a CI como uma competência estreitamente vinculada à competência linguística e, portanto, salienta que as atividades comunicativas são as que mais ajudam a fomentar a CI.

Palavras-chave: AICLE, Competência Intercultural, Docentes, Educação.

THE IMPORTANCE OF INTERCULTURALISM

Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL), as a methodological approach for the teaching of content through a foreign language includes the development of interculturalism in its theoretical background. Moreover, this interest coincides with other motives that drive the initiative of promoting Intercultural Education (IE) and the integration of its principles in the curriculum. The internationalisation of education at its different levels (mainly at the higher one), the educational goals for the 21st century, and the educational policies at supra-national levels are some of them (Knight, 2003).

Firstly, the fact that the internationalisation of education is mainstream at the tertiary level makes us ponder on the need to prepare our students to be able to take part in mobility programmes and to work together in class with students from a wide range of different cultural backgrounds. To do so, they need not only to be trained in linguistic skills but also to become interculturally competent (Murray, 2016).

Secondly, the educational objectives for the 21st century include the need to educate for the future (Lombardi, 2007), that is, to educate to live together in plural societies where diversity is constantly growing.

Thirdly, as it happens with bilingual and multilingual education, there is an increasing number of European educational policies in connection to the field of Intercultural Education (IE) and cooperation designed to face the difficult challenge to provide quality education for all, regardless of cultures, beliefs, customs and religions1. Actually, when the Council of Europe launched the project called The New Challenge of Intercultural Education (2002) they aimed at promoting awareness ofthe need to introduce the interfaith dialogue focusing on religion as an element of IE (Samers, 2004). One of the main goals was to put forward the introduction of the common European principles for managing diversity at school considering the greater social plurality of their countries (Faas, Hadjisoteriou & Angelides, 2014).

Peñalva and Soriano (2010) also highlighted the importance of interculturalism and Intercultural Competence (IC) to develop a European identity among citizens. In this context we understand interculturalism as the process of interaction and communication among different cultures being the horizontal alignment a key feature as equality and empathy are needed to achieve real and peaceful inclusion and coexistence. Besides, these goals also place special emphasis on the promotion of multilingualism to preserve the linguistic diversity of each region, while language skills of the citizens are enhanced to improve their job prospects and the understanding among people from different cultures.

This context must be taken into account when teachers design and plan the teaching-learning process in different aspects, such as the selection of the contents which could enhance students’ opportunities to acquire intercultural values (e.g. empathy, critical thinking, respect and cooperative work). This is why the role of teachers and their qualification directly influence students’ achievement (Darling-Hammond, 2000; Rahman, Jumani, Akhter, Chisthi & Ajmal, 2011).

In addition to these values, the content should not be directed simply to knowing aspects from a theoretical dimension, but it should also serve to help students plan a direct intervention in the real world. Content (to help establish various forms of communication and expression) allows them to develop critical thinking and be able to perceive the complex social reality from different points of view (Sales, 2012).

INTERCULTURALISM WITHIN CLIL

All in all, we consider that it is important to foster research studies on IC within CLIL because, up to the moment, research on the intercultural axis of CLIL is simply not enough (Méndez-García, 2013; Sudhoff, 2010). Moreover, these authors also state some of the advantages of using CLIL as a pedagogical approach to enhance learners’ intercultural communicative competence (ICC) (Byram, 1997) as well as their intercultural understanding. Some of these benefits are related to the real materials in the target language that teachers can use in the classroom; its authenticity helps students to get some insights on different foreign perspectives. Actually, the Information and Communication Technology (ICT) resources offer measureless opportunities to access this kind of teaching materials for content subjects. González and Borham carried out a study in which they used multicultural literary texts in order to promote ICC in CLIL contexts. It brought about great results and they mentioned that "by reading multicultural fictions that portray varied attitudes, feelings and assumptions on a given topic, students will acquire a richer and broader perspective on a theme… this would allow students to become interculturally competent as they explore a topic from foreign viewpoints" (González & Borham, 2012, p. 110).

Therefore, before analysing whether the IC axis is being implemented in teachers’ daily praxis, it is decisive to know how these teachers understand IC and which elements contribute to its development among students.

Intercultural interactions and communication processes are increasing in everyday life, so there is a need to be competent in this field. With regard to "Intercultural Competence" (IC) we mean -in line with most of the scholars’ views- a collection of behavioural, affective and cognitive skills that enable us to effectively and appropriately interact in intercultural situations and diverse cultural contexts (Bennett, 2008; Deardorff, 2006; Lustig & Koester, 2006; Perry & Southwell, 2011). Hence, the spreading of interest in IE is an answer to this imperative requirement. Scholars debate about its different assumptions and insights, the arguments for and against IE, and the ways in which it can be approached and taught at different educational levels, among other issues. Thus, IE must be seen as a basic dimension of general education for individuals, groups and communities, and not exclusively addressed to culturally-diverse schools (UNESCO, 2012). It covers more complexities rather than just the integration of immigrant students. It bets on the mutual enrichment; respect is the key for the practice because the final goal is the common social good in a democratic society. It offers a means to gain a complete and thorough understanding of the concepts of democracy and pluralism, as well as different customs, traditions, faiths and values. IE takes into consideration both the common objectives of all human beings and their specific peculiarities; it transcends the acknowledgement of equal dignity of all people in the world, regardless of their religion, culture and colour (Bell, 1989). "Intercultural education offers the opportunity to show real cultural differences, to compare and exchange them, in a single word, to interact: action in the activity; a compulsory principle in every educational relationship. It provides students with skills and abilities to manage activities with common norms and regulations. The aim is not assimilation or fusion, but encounter, communication, dialogue, contact, in which roles and limits are clear, but the end is open" (Portera, 2008, p. 488), so that interculturalism incorporates a number of elements, such as "pluralistic mind-set, meaning sensitivity to ethnocultural diversity and the rejection of all discrimination based on difference" (Bouchard, 2010, p. 440). It aims to know and respect other cultures, to develop a tolerant attitude towards ethnic minorities, to recognize and accept cultural pluralism as a social reality, to contribute to the establishment of a society where equal rights and equity prevail over discrimination and to help all students to develop their personal identity (Coulby, 2011). Its fundamental pedagogical principles are: improving and strengthening of the school, and the human and equality values of the society; recognition of the personal right of every student to receive the best personalized education; shaping their personal identity; positive appreciation of different cultures, languages, and their presence in school; diversity awareness and respect for differences without underestimating any of them; fighting against racism and discrimination; attempting to overcome prejudices and stereotypes; improving school success and promotion of the ethnic minority students; active communication and interaction among all the students, who will take part of the teaching-learning process democratically; active participation of the families in the school; and promotion of the relationships among different ethnic groups by inserting the school in the local community (Muñoz-Sedano, 2002).

In addition, IE suggests that social-justice and equity values should guide the transformation of both pedagogy and the curriculum in order to empower marginalized students and provide them with the corresponding skills that presuppose these transformation processes (Hadjisoteriou, Faas & Angelides, 2015; Leclercq, 2002; Zembylas & Iasonos, 2010). In this sense, UNESCO, seeking to guarantee universal primary education for all, launched the Guidelines on Intercultural Education and identified three key principles for IE that should be considered as a practical guide in this field (UNESCO, 2012, p. 32):

i. IE respects the cultural identity of the learner through the provision of culturally appropriate and responsive quality education for all. Teaching and learning materials should help students appreciate their cultural heritage and respect other identities, languages and values by introducing learners’ experiences and previous knowledge. Teachers need to put into practice culturally appropriate methods to ensure that all students feel themselves and their cultural roots part of the learning process through contextualised activities such as story-telling, drama, songs and visits to museums and monuments. It is essential to raise the interactions between the school and the community in which it is placed; moreover, the promotion of the participation of families and other communities’ members benefits the development of cultural and more sensitive activities, thus students become more aware of their role as vehicles of culture and they recognise not only the educational purposes of the school, but also the social ones and provide with extra support those who suffer any special cultural need or historical backlogs, so they can manage to equally participate in the education process.

ii. IE provides every learner with the cultural knowledge, attitudes and skills necessary to achieve active and full participation in society. It mainly refers to the provision of equal access to education in all its levels regardless of the students’ cultural background. Teachers must aim to incorporate learners from minority cultural groups into the learning process and to create active learning environments through projects in which students acquire cultural skills and have the chance of communicating and working together with others.

iii. IE provides all learners with cultural knowledge, attitudes and skills that enable them to contribute to respect, understanding and solidarity among individuals; ethnic, social, cultural and religious groups, and nations. The curricula should contribute by involving knowledge about cultural heritage in subjects such as History, Art, Languages, Literature, Technology, etc. being aware of how the same content can be approached from different cultural perspectives, and developing interdisciplinary projects that enable learners to understand the culture values underneath the content and the diverse ways of interpreting it. Furthermore, the use of ICT and exchange programmes facilitates direct and regular contacts between pupils and educators from different countries. These international networks enrich the learning process as they all pursue similar goals.

Furthermore, IE states that teachers and learners should promote education for empathy as it is essential and it allows gathering life experience of the other as one’s native life experience (Banks, 2006; Pasquale, 2015).

Focusing on the Spanish educational context, IE is one of the main points of interest for the Spanish Ministry of Education which over the last decade has funded, promoted and developed studies and reports related to diversity awareness and cultural diversity in educational contexts. This trajectory started in 2006 when the CIDE (‘Centre for Educational Research and Documentation’ in English) created the CREADE (that stands for ‘Centre of Resources for Attention to Cultural Diversity in Education’) whose acronym in Spanish stands for ‘Centro de Recursos para la Atención a la Diversidad Cultural’. This is a website translated into thirteen languages whose aim is to bring together, develop and facilitate cultural resources in response to the demands of professionals in the social and educational fields, as well as to promote and disseminate research and innovation in intercultural studies. Some plans promoted by this Centre are carried out in Spanish classrooms, which can help us to understand where they place the emphasis: welcoming plan, intercultural mediation program, temporary classroom for linguistic adaptation, extracurricular activities based on linguistic support and Spanish virtual classroom.

INTERCULTURAL COMPETENCE IN CLIL

As for IC, most of the literature has been focused on adults, not children. Kramsch in Takeuchi (2015, p. 47) stated that one of the reasons why these studies are limited is "because of the assumption that the attainment of IC presumes a cognitive ability and morality that many young children have yet to acquire." Nevertheless, "there are studies whose outcomes point out that ‘any subject can be taught effectively to children at any stage of development, and thus the issue of intercultural competence is relevant for the youngest of children’" (Byram & Doye in Takeuchi, 2015, p. 47).

Among IC goals, we can underline the following one: to develop the ability to interact with human beings with different identities and their own one; it is a lifelong process which rarely is complete. Some children do not have their first intercultural contacts until they are teenagers, but it does not mean that they should not pay attention to this competence along their Primary Education, as it would be adequate to anticipate this training they will need in the future. Byram, Gribkova & Starkey (2002) also agree that IC instruction should be continuous due to the fact that:

"… everyone’s own social identities and values develop, everyone acquires new ones throughout life as they become a member of new social groups; and those identities, and values, beliefs and behaviours they symbolise are deeply embedded in one’s self. This means that meeting new experiences, seeing unexpected beliefs, values and behaviours, can often shock and disturb those deeply embedded identities and values, however open, tolerant and flexible one wishes to be. Everyone has therefore to be constantly aware of the need to adjust, to accept and to understand other people - it is never a completed process." (p. 11)

Consequently, we believe that IC needs to be involved in and immerse within a continuous and integrated process of learning that ensures that children at the end of their Primary Education will be

able to adapt and get on properly among either majority and minority cultural groups, i.e. they will be able to develop knowledge about other cultures, skills to communicate in different foreign languages, positive attitudes towards cultural diversity, among many others.

As we mentioned at the beginning of the paper, the general objective of this study is to analyse how interviewed CLIL teachers understand IC and which elements they think promote its development. It is divided into three different specific objectives:

-

To examine the definition of IC given by in-service CLIL teachers.

-

To analyse which elements contribute to its development in the school and in the classroom.

-

To create a network that explains CLIL teachers’ understanding of IC.

METHOD

Design

This study is part of a larger research on the implementation of the intercultural axis of CLIL by teachers. Data collected come from the textual and conceptual analysis of an open-question survey which was analysed by following both qualitative and quantitative methods. It also consists of a descriptive study aimed at exploring teachers’ previous knowledge about IC and the different elements that enhance it according to their opinions.

A mixed research method (MMR) helped us not only to approach the knowledge of social reality through the study of the teachers’ speeches, but also to analyse them in depth since we applied both qualitative and quantitative analyses to our gathered data. From this, we obtained direct knowledge from reality, neither mediated by conceptual or operational definitions, nor filtered by measuring instruments with a high degree of structuring (Flick, 2004).

Participants

The surveyed sample consisted of 59 teachers from a total of 87 teachers who were teaching their content subject through a foreign language (English) at Primary Education level in different schools in the city of Cordoba during the academic year 2015/2016. Out of the total sample, 66.1% were female and 33.9% were male whose average age was 35 years old. Moreover, around half of them (52.5%) had been working for fewer than ten years.

Data Collection Techniques

The questionnaire used as a tool for collecting the data consisted of a set of open questions on issues related to understanding about IC in Primary Education, the teaching contexts and the different elements of the teaching planning (objectives, contents, competences, methodological resources and evaluation). It was written in Spanish as it was the mother tongue of all respondents, so it ensured that they would understand and answer each question more easily.

After taking into account the considerations and contributions of the panel of experts (Delphi Method), the number of questions was reduced from 25 to 16, and it was also improved in terms of clarity, coherence, appropriateness and wording.

This was finally set as a medium-size questionnaire with clear and simple questions which avoid misunderstanding among the survey respondents. Some of the questions were made up of two sub-questions because participants were firstly asked a total question (to which they had to answer either yes or no), and then they had to either justify this decision (why), or explain the way in which they carried out a specific task (how). This way, the answers were exhaustive and complete, allowing us to test our hypotheses and infer relevant conclusions. The dimensions in which the questions were gathered were established according to a deep literature review and taking into account the elements included within every teacher planning process. Before getting the final version of the questionnaire (and right after introducing the corresponding modifications according to the experts’ opinions), we selected a small sample of ten participants to hand the questionnaire in advance to verify that it fitted the objectives of this research.

For this paper we use the first dimension of the questionnaire, which corresponds to the teachers’ understanding of IC.

Procedure

Primary Education CLIL teachers answered the questionnaire during the first term of the academic year 2015/2016. First of all, in order to start collecting the data, it was necessary to get the corresponding authorization from each school. Once we obtained a positive response, the research team was in charge of meeting the teachers so as to inform them about the purpose of the research, the instructions to complete the open-question questionnaire and the anonymity of their answers. Then, we handed out the questionnaire and we stayed with them while they filled it in, so in case they did not understand any question, we could help them. CLIL teachers in particular and schools in general were quite interested in this research, so they did it willingly. It took them an average of fifty minutes to answer the questionnaire.

Atlas.ti has been chosen as the most suitable software to process our data due to a number of reasons, namely: its usefulness to do on-screen coding, and the possibility it opens to build mind maps (which visually explain the results) as well as to create links among them. The fact that it allowed to export our data to SPSS and then apply purposefully quantitative statistical processing was also decisive.

Firstly, we used the two options of Atlas.ti: textual analysis to obtain the corresponding categories and subcategories; and conceptual analysis to establish the relationships among them by creating the appropriate networks.

The analysis process was as follows:

-

Information registry. It is necessary to register the information gathered from the questionnaires as it is the basic material for the analysis. To do so, we assigned a number to each questionnaire, too.

-

Creation of a new project: the Hermeneutic Unit (HU). The HU is a container concept referring to one entity which includes everything that is relevant to a particular project. It is equivalent to a folder with a name where primary documents are included. In our project, these documents were the questionnaires answered by our sample.

-

Analysis units, codes and notes. Working with the documents (questionnaires) means selecting the quotes and establishing codes and notes. The analysis units or quotations are pieces of the primary documents that have been marked as such in Atlas.ti and they can be made up of simple words, symbols or semantic propositions (e.g. isolated sentences or groups of them) with an inner sense. Codes are key words, indicators of concepts or expressions that are interesting to consider in our research. A quotation can be assigned to different codes, where one single code can be related to different quotations. The notes (called memos in Atlas.ti) are usually short texts containing ideas, which are associated with some of the other types of components and should not be confused with the explanatory comments that any element can involve.

-

Coding process. A key task in the process of data reduction consists of the use of codes that are usually labelled with an abbreviation, symbol or mark that apply to sentences or paragraphs. It is the initial stage of data processing. The codes must be related to the nature of the data, to the theory explained in chapter one, two and three, and to the research itself. Furthermore, this process includes gathering and analysing all data relating to topics, ideas, concepts, interpretations and propositions.

-

Categorising process. It aims to bring together or conceptually classify a set of elements with a similar meaning.

Then, as we mentioned before, we exported the codes to SPSS in order to apply different quantitative statistical treatments. We applied a descriptive analysis (frequency and percentages) of the data derived from the questions that enabled us to design some tables and graphics to clearly present the results, too.

RESULTS

As indicated previously, the results of this research correspond to a broader study about how CLIL teachers implement the intercultural axis across the different curricular elements. Specifically, this paper presents the results that correspond to the first dimension of the questionnaire which includes two questions: ¿Qué entiende por competencia intercultural en Educación Primaria?¿Qué elementos cree que pueden favorecer el desarrollo de la competencia intercultural en la dinámica del aula?As mentioned before, these two questions aim to explore not only how CLIL teachers understand IC in Primary Education, but also which elements they think can facilitate their students’ development of such competence.

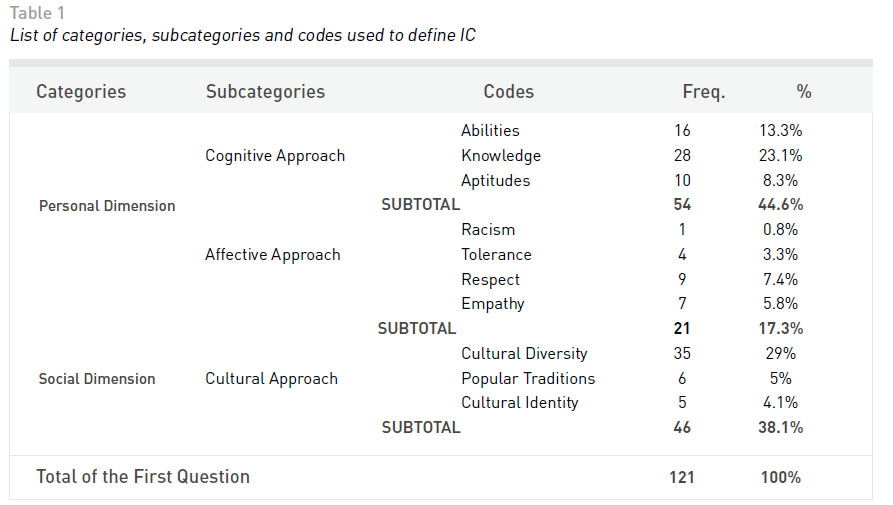

Then, we present the results of the categorising process as well as the frequencies and percentages of each code derived from this analysis in accordance with the objectives (see Table 1).

The first objective is to examine the definition of IC given by in-service CLIL teachers. Surveyed teachers refer to two dimensions when talking about IC: personal and social dimensions.

On the one hand, personal dimension (dimensión personal) is divided into two subcategories, the cognitive (enfoque cognitivo) and the affective (enfoque afectivo) approaches. On the other hand, the social dimension (dimensión social) includes one subcategory that is the cultural approach (enfoque cultural).

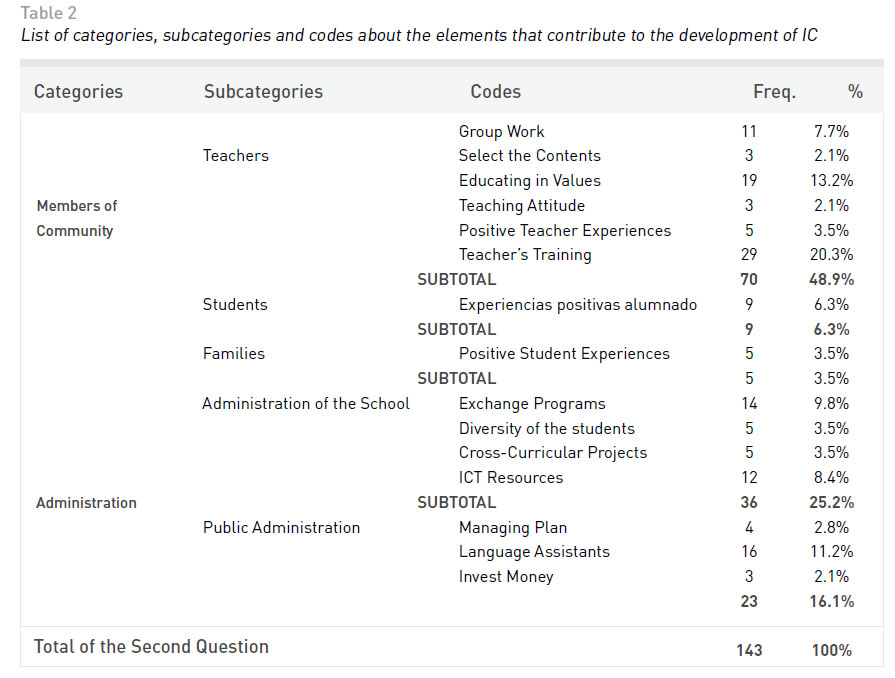

Regarding the elements that contribute to the development of the IC in the classroom, there are two categories: members of the community (miembros de la comunidad) and of the administration (administración). The first one includes three subcategories, namely teachers (profesorado), students (estudiantes) and families (familias) while the second one involves only two: the administration of the school (administración del centro) and the public administration (administración pública).

The cognitive approach is highly mentioned (44.6%) because teachers attach certain importance to having knowledge about other cultures in order to be interculturally competent at Primary Education level, while cognitive abilities and aptitudes are less mentioned (showing 13.2% and 8.3%, respectively). As for the affective approach, the two most frequent issues have to do with respect for people from other cultures (7.4%), and being empathetic in multicultural contexts (5.8%). Teachers frequently refer to the social dimension (38.1%). Valuing the existing differences originated by cultural diversity is the most common feature they refer to (29%), while developing cultural identity (4.1%) and appreciating the diverse traditions (5%) are less common categories.

The second specific objective of the study was to analyse which elements contribute to its development in the school and in the classroom (see Table 2). The most frequent elements have to do with teachers (48.9%). Among them, teachers give thought to whether they devote time to group work (7.7%), how they select the contents (2.1%), the importance they attach to educating in values (13.2%), their attitude when teaching (2.1%), their positive intercultural experiences throughout their lives (3.5%), and their previous training in this competence (20.3%). Moreover, they also think that the experiences that students have with students from other countries (6.3%) and the participation of the families in the schools’ projects (3.5%) are important.

Then, elements related to the administration also play a key role in developing IC according to our surveyed teachers. In addition, the role of the school administration is more frequent (25.2%) than the role of the public administration (16.1%). Within the administration of the school, the exchange programs are the most recurrent item (9.8%) followed by the promotion of ICT resources (8.4%), and the diversity of the students in the school and the cross-curricular projects (both 3.5%). Teachers refer to the Public Administration in terms of the need to have an excellent managing plan (2.8%), to provide schools with language assistants (11.2%) and to invest money in bilingual schools (2.1%).

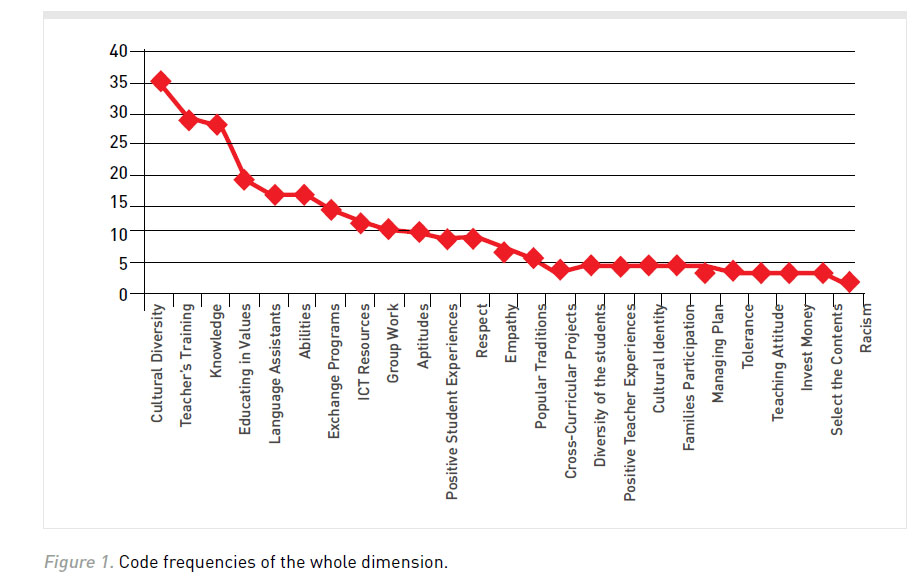

Altogether, this line graph provides us with a holistic vision of the use of codes in the first dimension of the questionnaire (see Figure 1). It lets us know how teachers understand IC and which elements help to its progression. The most used codes are cultural diversity, teacher training, knowledge about other cultures and educating in values, whereas those codes placed on the right side of the graphic are not that important for them (e.g. teachers’ attitude, economic investment, the way teachers select contents, and racism).

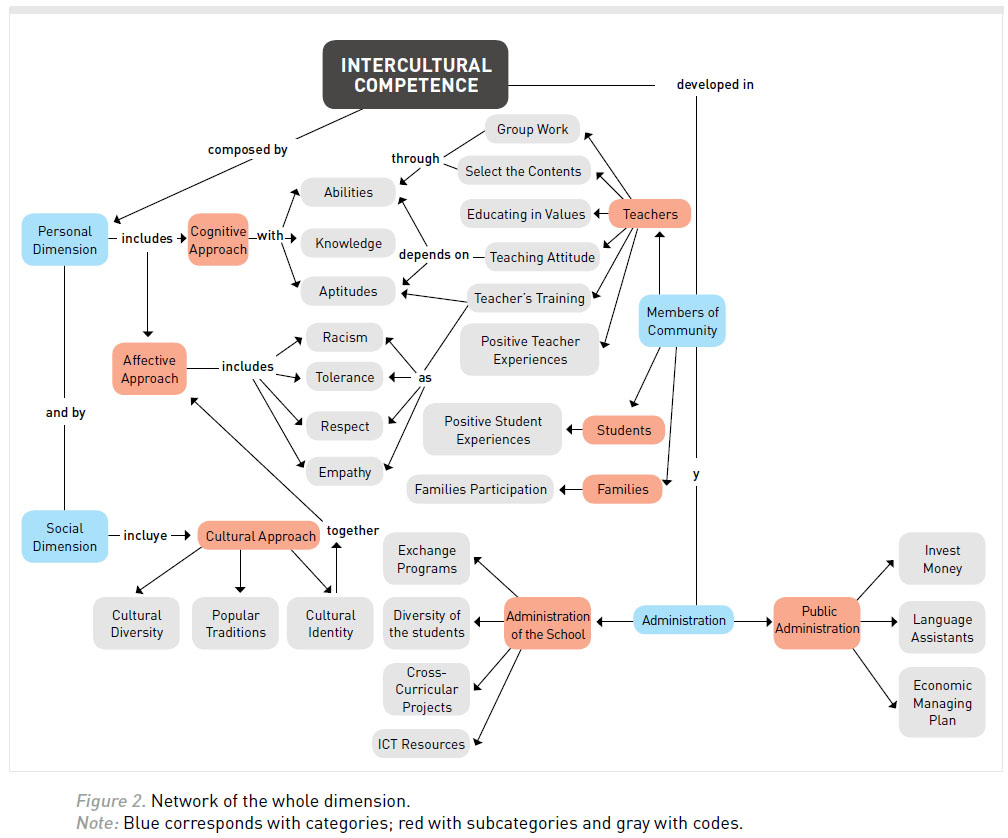

Then, in order to achieve the third objective, we carried out the conceptual analysis dealing with the interpretation of the elements previously created in the textual analysis and the closeness to their meaning. This process entails a higher level of analysis of both codes and categories aiming to obtain structures that respond to the teachers’ conception of IC in CLIL contexts (see Figure 2).

First of all, teachers define IC at Primary Education under two different categories, namely personal dimension (dimensión personal) and social dimension (dimensión social). Within the personal dimension, we distinguish between cognitive and affective elements that shape this competence. In regard to this, teachers state that it is necessary to develop a variety of abilities, knowledge and aptitudes to become interculturally competent. Moreover they associate this competence with specific values such as tolerance, respect and empathy, as well as to acting against racism in any context. Surveyed teachers also refer to the category of social dimension, which includes one subcategory related to the cultural approach (enfoque cultural). Living together with people from different cultures, knowing their popular traditions, building your own cultural identity (regardless of who you coexist with) and respecting the possible cultural differences also mean being interculturally skilled.

Then, they understand that there is a wide range of elements which facilitate the promotion and improvement of such competence. We have two dimensions herein: members of the community (miembros de la comunidad) and administration (administración). On the one hand, teachers, students and families can influence the strengthening of IC. As for teachers, they should design tasks that help students work in groups, pay attention when selecting the contents, and educate in values. Their previous training connected to IE, their attitude in the classroom (practise what you preach) and whether they have had positive intercultural experiences abroad could contribute to furtherance in this competence. This last element is also mentioned as crucial among students. Then, participation of families in school life is another element some of them refer to.

On the other hand, the category called administration is divided into two subcategories. The school and its administration are crucial in this process. Organising exchange programs for staff, students and teachers, the diversity of students they have, ICT resources and the way they organise cross-curricular projects that involve the whole centre are key elements to enhance IC. The other subcategory that teachers refer to has to do with the Public Administration (Administración Pública) because not only the economic investment is important, but also the promotion of teacher assistants.

DISCUSSION

In regards to the analysis of CLIL teachers’ understanding of IC (which comprised two questions), we can confirm that surveyed teachers believe that being interculturally competent at Primary Education means having a set of abilities, such as being able to communicate and interact with people from different cultures by using different foreign languages; to learn from each other’s differences, knowledge (e.g. customs and traditions of other cultures, religious beliefs, aptitudes), and values (such as tolerance, respect and empathy) (teacher a: la competencia intercultural es la capacidad para relacionarse y comunicarse a través de una lengua extranjera con personas de distintas culturas y tener empatía con ellas). They also understand IC as the ability to develop one’s cultural identity as well as to respect and learn from others’ cultural identities. This understanding relies on the elements the definition of ‘competence’ includes (knowledge, values and skills), and it is similar to how other authors define IC (e.g. Byram, 1997; Bennett, 2008; Deardorff, 2006; Perry & Southwell, 2011) since they include personal, cognitive and affective skills. A large number of teachers also refer to the ability to communicate in a foreign language, which agrees with Byram’s concept of Intercultural Communicative Competence (ICC) because they understand that learners need to command the foreign language in order to become intercultural speakers, at the same time that it is also necessary to enhance their IC. Here it is relevant to point out that one of the interviewed teachers stated that to become competent in this field, it is not possible to show a discriminatory or racist behaviour (teacher b: para ser competente interculturalmente el respeto es un valor fundamental que ha de ser desarrollado en todo el alumnado; teacher c: educar en valores como la tolerancia y el respeto y trabajar contenidos sobre otras culturas fomentan esta competencia y evita actitudes racistas entre el alumnado). This perspective coincides with Bouchard (2010) and Pasquale (2015) who recognise that the multiculturalism of current societies is also reflected in school contexts, so it is necessary to implement pre-designed educational strategies to prevent and avoid racism. The definition given by the fifty-nine teachers in our sample is also in line with key aspects that UNESCO (2012) highlights both in their documents and strategies on IE in Primary Education. We refer here to the aptitude to interact and to learn from each other (mutual enrichment), and to go beyond passive coexistence in order to achieve social progress.

We should also mention that our sample refers to cultural diversity (the most cited code: 35 times) and to the importance of being able to peacefully live together when they define the concept of IC (teacher d: la competencia intercultural acerca al alumnado a otras realidades culturales distintas a las suyas reconociendo la diversidad de identidades, las diferencias entre ellas y haciéndolos reflexionar sobre las suyas) , which could be due to the fact that the Spanish Ministry of Education has promoted different projects regarding diversity awareness and cultural diversity in educational contexts. An example of this is the Centre of Resources for Attention to Cultural Diversity in Education which provides schools and teachers (since 2007) with online resources to enhance IE in Spain. Most of them aim to make students aware of the existing differences between cultures so as to increase their cultural knowledge as well as the possibility to learn from each other. In addition, these resources are classified attending to the peculiarities of each Autonomous Community. For Andalusia, this Centre is of high interest as its educational legislation aims to cater for different abilities, learning pace and style, students’ motivation and interests, socioeconomic, cultural and linguistic situations in order to facilitate the acquisition of the key competences of the curriculum.

As for the elements than can contribute to the advancement of such competence, we found an array of items. Surveyed teachers attach importance to whether teachers have received training in terms of interculturality, IE and IC (29) (teacher e: una buena disposición y formación por parte del profesorado son necesarias para trabajar la competencia intercultural), or it not is decisive because they cannot implement it if they are not competent enough in the area. It means that teachers firstly need to be competent in whichever area they are going to work in before teaching students. This opinion is in line with that of those authors who establish a narrow relationship between teacher training and students’ achievement, such as Darling-Hammond (2000) and Rahman et al. (2011).

Another important factor here is the relationship that teachers establish between IC and the education in values (the fourth most cited code: 19) (teacher f: en el aula se puede favorecer el desarrollo de esta competencia educando en valores). On the one hand, this connection is justified because following their definition of ‘competence,’ values are an important part of it. On the other hand, they are convinced that there are a series of values that people need to develop in order to achieve peaceful coexistence. Among these values, teachers highlight tolerance (4), respect (9) and empathy (7). This idea coincides with the understanding of Portera (2008) and Coulby (2011) who stated that education should be based on respect for everybody inside and outside school contexts, and it must develop tolerant attitudes towards ethnic minorities so as to protect equity rights.

Our assumption is that IE prepares people to be able to live together harmoniously because it leads to recognising the otherness. Then, as values are teachable and achievable, to educate in value means to integrate the principles of IE and IC with the aim of training societies for a peaceful and friendly coexistence.

Then, teachers in our sample mentioned other elements in their answers to the questionnaire such as language assistants, school exchanges, the use of ICT in the classroom, and the introduction of international and intercultural experiences for both teachers and students, so they are placed at the centre of their own intercultural learning (teacher g: llevar a cabo proyectos de intercambio es decisivo en este propósito). Their justification lies on the fact that these elements bring the real world closer to the classroom. For instance, international exchanges give students the opportunity to get to know and discover different cultures first-hand and with direct contact with foreigners; technological resources enable 21st century communication with people from different countries, and the use of real materials or realia (audio, photos and videos) together with the relation of positive experiences abroad with any subject content can help them acquire this competence easily and with higher motivation. UNESCO (2012) also mentions some of these elements as well as the participation of families in the school culture within its statement of the three principles of IE.

A small number of our surveyed teachers stated that this competence should be more important when there are students from different cultural backgrounds (cited 5 times) in the classroom. It is opposed to what institutions, associations and relevant scholars think (e.g. Portera 2008) because both IE and IC must be addressed to everybody and not only to minorities, as it would turn into an assimilationist model (Muñoz-Sedano, 2002) which is strongly criticised by the International

Association for Intercultural Education (IAIE), which believes that IE should be addressed to everybody in multicultural societies, and then, to teachers, teacher trainers, researchers and policy makers2.

Within this dimension, the investment (cited 3 times) and the way these resources are managed (4 times) influence the development of IC among students. Finally, they pointed out two key strategies (the selection of contents and group work) as the best ideas to pursue this goal.

Taking into account the codes that surveyed teachers have used to answer the questions of the first dimension and their frequencies, we can say that not many teachers have an idea of what IC is and how they can help students achieve it, but we would like to highlight here that their perspective is mainly language-oriented (linguistic and communicative skills) instead of seeing this competence as a cross-curricular one. We reach this conclusion after analysing that teachers mainly named the ability to communicate with foreigners; one of them even stated that IC means to be able to communicate with people from different countries through a foreign language (teacher h: el alumnado en Educación Primaria es competente interculturalmente si puede comunicarse con personas de otros países a través de una lengua extranjera).

To conclude, it has been observed that surveyed teachers associate IC with linguistic competence, so they believe that the activities they promoted in their schools involving communicative activities (mainly oral) in a foreign language can make a contribution to intercultural learning and understanding (specially exchange programs and the presence of foreign teacher assistants in the classroom). In addition, they associate this kind of activities and initiatives to the betterment of values such as tolerance, respect and empathy.

Every research provides some benefits at the same time it faces some limitations. The main limitation of this study has to do with the sample. Nowadays it is quite difficult to get universal access to Spanish public schools because they are overloaded with their daily work and with research carried out by the institutions. Moreover, to get their participation, researchers need to go through a long and tedious process to obtain the authorization of the Department of Education of the Andalusian Government. This was the reason we resorted to private and semi-private schools that were interested in contributing to our research, so the sample was smaller. Moreover, it is important to bear in mind that the schools that have participated in this study are religious (mostly Catholic), so it could have somehow influenced our results. Then, it should be noted that we must be cautious with the results and conclusions of these results.

In regards with future lines of research, it would be interesting to design a quantitative tool (Likert scale), subject to a validation process to finally obtain an accurate tool which can be applied to any CLIL context, and which could enable us to reach a bigger sample.

REFERENCES

Banks, J. A. (2006). Approaches to Multicultural Curriculum Reform. In J. A. Banks, Race, Culture and Education (pp. 181-190). London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Bell, G. H. (1989). Developing a European dimension of teachers training curriculum. European Journal of Teacher Education, 12(3), 229-237. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0261976890120303 [ Links ]

Bennett, M. J. (2008). On becoming a global soul. In V. Savicki, Developing intercultural competence and transformation: Theory, research and application in international education (pp. 13-31). Sterling: Stylus Publishing. [ Links ]

Bouchard, G. (2010). What is interculturalism. McGill Law Journal, 56(2), 435-468. [ Links ]

Byram, M. (1997). Teaching and assessing intercultural communicative competence. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. [ Links ]

Byram, M., Gribkova, B. & Starkey, H. (2002). Developing the intercultural dimension in language teaching. A practical introduction for teachers. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. [ Links ]

Coulby, D. (2011). Intercultural Education and the crisis of globalisation: Some reflections. Intercultural Education, 22(4), 253-261. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14675986.2011.617418 [ Links ]

Darling-Hammond, L. (2000). Teacher quality and student achievement. Education policy analysis archives, 8(1), 1-17. [ Links ]

Deardorff, D. K. (2006). Assessing intercultural competence in study abroad students. In M. Byram & A. Feng, Living and studying abroad: Research and practice (pp. 232-256). Bristol: Multilingual Matters. [ Links ]

Faas, D., Hadjisoteriou, C. & Angelides, P. (2014). Intercultural education in Europe: policies, practices and trends. British Educational Research Journal, 40(2), 300-318. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/berj.3080 [ Links ]

Flick, U. (2004). Introducción a la investigación cualitativa. Madrid: Morata. [ Links ]

González, L. M. & Borham, M. (2012). Promoting intercultural competence through literature in CLIL contexts. Journal of the Spanish Association of Anglo-American Studies, 34(2), 105-124. [ Links ]

Hadjisoteriou, C., Faas, D. & Angelides, P. (2015). The Europeanisation of intercultural education? Responses from EU policy-makers. Educational Review, 67(2), 218-235. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2013.864599 [ Links ]

Knight, J. (2003). Updated definition of internationalization. International Higher Education, 33, 1-4.

Leclercq, J. M. (2002). The lessons of thirty years of European co-operation for Intercultural Education. Strasbourg: Steering Committee for Education. [ Links ]

Lombardi, M. M. (2007). Authentic learning for the 21st century: An overview. Educause learning initiative, 1, 1-12.

Lustig, M. W. & Koester, J. (2006). Intercultural competence: Interpersonal communication across cultures. Boston: Pearson. [ Links ]

Méndez-García, M. C. (2013). The intercultural turn brought about by the implementation of CLIL programmes in Spanish monolingual areas: a case study of Andalusian primary and secondary schools. The Language Learning Journal, 41(3), 268-283. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2013.836345 [ Links ]

Muñoz-Sedano, A. (2002). Hacia una Educación Intercultural: Enfoques y Modelos. In A.C. Del Canto, et al., La Educación Intercultural: Un Reto en el Presente de Europa (pp. 47-53). Madrid: Consejería de Educación de la Comunidad de Madrid. [ Links ]

Murray, N. (2016). Dealing with diversity in higher education: awareness-raising and a linguistic perspective on teachers’ intercultural competence. International Journal for Academic Development, 21(3), 166-177. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2015.1094660

Pasquale, G. (2015). Towards a New Model of Intercultural Education into Italian School. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 191, 2674-2677. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.04.280

Peñalva, A. & Soriano, E. (2010). Objetivos y contenidos sobre interculturalidad en la formación inicial de educadores y educadoras. Estudios sobre Educación, 18, 37-57.

Perry, L. B. & Southwell, L. (2011). Developing intercultural understanding and skills: Models and approaches. Intercultural Education, 22(6), 453-466. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14675986.2011.644948 [ Links ]

Portera, A. (2008). Intercultural education in Europe: Epistemological and semantic aspects. Intercultural Education, 19(6), 481-491. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14675980802568277 [ Links ]

Rahman, F., Jumani, N. B., Akhter, Y., Chisthi, S. U. H. & Ajmal, M. (2011). Relationship between training of teachers and effectiveness teaching. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 2(4), 150-160. [ Links ]

Sales, A. (2012). La formación intercultural de profesorado: estrategias para un proceso de investigación-acción. Educatio Siglo XXI, 30(1), 113-132. [ Links ]

Samers, M. (2004). An Emerging Geopolitics of ‘Illegal’ Immigration in the European Union. European Journal of Migration and Law, 6(1), 27- 45. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1571816041518750

Sudhoff, J. (2010). CLIL and Intercultural Communicative Competence: Foundations and Approaches towards a Fusion. International CLIL Research Journal, 1(3), 30-38. [ Links ]

Takeuchi, A. (2015). Developing a Scale of Children’s Intercultural Competence: Issues and Challenges. Maebashi Kyoai Gakuen College, 1, 45-58. UNESCO (2012). Guidelines on Intercultural Education. Paris: Author.

Zembylas, M. & Iasonos, S. (2010). Leadership styles and multicultural education approaches: An exploration of their relationship. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 13(2), 163-183. [ Links ]

1. http://ec.europa.eu/education/policy/strategic-framework_en

2. http://www.iaie.org/1_about.html

Received: 09-28-16

Revised: 03-01-17

Accepted: 03-23-17

Published: 05-05-17