Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista Digital de Investigación en Docencia Universitaria

versión On-line ISSN 2223-2516

Rev. Digit. Invest. Docencia Univ. vol.11 no.2 Lima jul./dic. 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.19083/ridu.11.583

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Foreign Language Training in Translation and Interpreting Degrees in Spain: a Study of Textual Factors

Enseñanza de lenguas extranjeras en Facultades de Traducción e Interpretación españolas: estudio de factores textuales

Ensino de línguas estrangeiras em Faculdades de Tradução e Interpretação de Espanha: estudo de fatores textuais

Laura Cruz García* (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7826-0142)

Departamento de Filología Moderna, Facultad de Traducción e Interpretación, Universidad de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, España

ABSTRACT

Foreign language teaching and learning has received a considerable amount of scholarly attention across different stages of education, particularly in the case of English. Apart from language training in general contexts, language for special purposes also constitutes a prolific field of study. However, less research has been conducted on the foreign-language training needs of trainee translators and interpreters and the corresponding teaching methodologies. In order to gain insight into actual teaching practices in this area in Spanish universities, we have studied the methodological approaches used in the classroom by 58 foreign language lecturers at 13 Translation and Interpreting Faculties in Spain, through a research Project of the Universidad de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria (Spain). Information was compiled from the responses to an ad hoc questionnaire created for this purpose, sent out by email and filled out on a voluntary basis. This article describes the uses made of texts in foreign language classes, to which end we will focus on the responses to one of the questions posed in the questionnaire. One of the key findings of the study is the preponderance of lexical, semantic, morphological and syntactic features, potentially implying teaching methodologies akin to those used in other education settings.

Keywords: foreign language teaching, translation and interpreting trainees, textual factors

RESUMEN

La enseñanza de lenguas extranjeras ha sido ampliamente explorada, especialmente en el caso del inglés, en diferentes niveles educativos. Además de la formación en idiomas en contextos generales, las lenguas para fines específicos han constituido un campo de estudio prolífico. Sin embargo, cuando se trata de la enseñanza de lenguas orientada a los futuros traductores e intérpretes, se ha ahondado poco en sus necesidades y en las metodologías docentes que requieren. Para conocer la práctica docente universitaria en la formación lingüística de traductores e intérpretes en España, mediante un proyecto de investigación de la Universidad de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria (España), realizamos un estudio sobre una serie de aspectos metodológicos donde participaron 58 profesores de lenguas extranjeras de trece facultades españolas de Traducción e Interpretación. Lo hicieron mediante una encuesta creada ad hoc distribuida por correo electrónico y que respondieron desinteresadamente. Concretamente, el objetivo de este artículo es describir cómo se explotan los textos en las clases de lenguas extranjeras, para lo cual nos centraremos en las respuestas a una de las preguntas del cuestionario. Un hallazgo fundamental del estudio es la preponderancia de los aspectos léxico- semánticos y morfosintácticos, lo que podría implicar un método de enseñanza muy similar al de otros contextos educativos.

Palabras clave: enseñanza de lenguas extranjeras, estudiantes de traducción e interpretación, factores textuales expert

RESUMO

O ensino de línguas estrangeiras tem sido amplamente explorado, especialmente no caso do inglês, em diferentes níveis educacionais. Além do treinamento linguístico em contextos gerais, as linguagens para fins específicos constituíram um campo de estudo prolífico. No entanto, quando se trata de ensino de línguas voltadas para futuros tradutores e intérpretes, pouco foi feito sobre suas necessidades e as metodologias de ensino que eles exigem. Conhecer a prática de ensino universitário no treinamento linguístico de tradutores e intérpretes em Espanha, através de um projeto de pesquisa da Universidade de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria (Espanha), realizamos um estudo sobre uma série de aspectos metodológicos envolvendo 58 professores de línguas de treze faculdades de tradução e interpretação da Espanha. A informação foi coletada através de uma pesquisa criada ad hoc distribuída por e-mail e eles responderam desinteressadamente. Especificamente, o objetivo deste artigo é descrever como os textos são explorados em aulas de língua estrangeira, para o qual nos concentraremos nas respostas a uma das perguntas do questionário. Um achado fundamental do estudo é a preponderância dos aspectos lexical-semântico e morfossintático, o que poderia implicar um método de ensino muito semelhante ao de outros contextos educacionais.

Palavras-chave: ensino de línguas estrangeiras, estudantes de tradução e interpretação, fatores textuais

Taking into account the key tasks that translators and interpreters have to carry out in their daily professional work, in order to prepare trainees for their professional future in the field of translation and interpreting, foreign language classes have to focus on specific skills, such as the comprehension of long written and spoken texts; the capacity to deduce or infer meaning from context; the appropriate use of a range of relevant printed and on-line dictionaries, glossaries and other resources; a command of a broad range of registers, fields of knowledge, dialects, accents and specializations, as well as becoming familiar with common text types in the target culture. It is therefore clear that trainees in this field have a number of special needs that go over and above the use of language in general contexts that must necessarily be contemplated in the teaching method used in the classroom. Both the mother tongue and the foreign languages are tools of the trade, means to an end, for professional translators and interpreters. But how is this specialised undergraduate training of future professionals actually carried out? Tendencies in language learning methodology have varied over the years, offering a wide range of methodological proposals that can be applied in different contexts, from language learning at early ages right through to adult training in specialist contexts (languages for specific purposes).

In previous papers (Adams & Cruz García, 2016, 2017), attention has been drawn to the fact that the teaching of foreign languages for trainee translators and interpreters could almost be considered a kind of "Cinderella" within the field of foreign language instruction; as a specific field of study it has received little academic attention in comparison with the teaching of foreign languages for general purposes, or that of languages for specific purposes, for example. However, recognition of the specificity of this field can be seen in a small, but highly specialized, body of work going back approximately twenty years, leading to tailor-made methodological proposals, such as that put forward by Beeby (2004).

Thus, Brehm Cripps’ early work (1996) outlining the main objectives for the first foreign (or B language) for translators and interpreters was later further developed, in collaboration with Hurtado Albir (Brehm Cripps & Hurtado Albir, 1999), into six main objectives to be covered in foreign language classes for trainee translators, given in descending order of importance (subsequently broken down into 22 specific goals), as follows: (i) reading comprehension, (ii) writing, (iii) use of oral language, (iv) consolidation and development of linguistic knowledge, based on contrasting the B language with the mother tongue, (v) broadening socio-cultural knowledge and (vi) making students familiar with the use of documentation sources. Berenguer (1996) developed a specific language teaching proposal for German, specifically aimed at would-be translators and interpreters with exercises to develop the five main skills identified as key, including reading comprehension exercises (specifically aimed at the particular reading skills required by translators). She introduces exercises to separate the two languages in contact that focus on differences in writing conventions, vocabulary, grammar and text types.

According to Ruzicka Kenfel (2003), also working in Spain, the teaching of German as a foreign language for future translators and interpreters has to ensure that students have the requisite level of "formal correctness" in the language, which includes command not only of vocabulary but also of morphology and syntax. This goes hand in hand with textual competence, present in the work of almost all experts working in this field today but for which a solid knowledge and correct use of grammar plays an essential part. Incoming undergraduates’ command of their B and C languages is of course dependent on their previous knowledge and experience. Notwithstanding the obvious differences typically found in any heterogeneous group of language learners, and the fact that many faculties offer instruction in the C language assuming no previous knowledge, the tendency over recent decades to opt for communicative methodologies in secondary education has clearly had an impact on the starting points that university trainers can establish for instruction in the B language. While the communicative approach has many benefits, and is the product of the socio-cultural reality in which we live, the concomitant preference for focusing on meaning rather than form leads to pre-University learners having a lesser grasp of formal aspects in general. For trainee translators and interpreters, this may be viewed as a weaker command of the basic building blocks required both to decode and produce written and oral texts. In Beeby’s words:

Previously, the first-year language teacher could enjoy the pleasant task of activating passive language skills with students who had little experience of participating in communicative situations in English. Today, students have been taught to "communicate" at school and to talk to English speakers in Spain and abroad. Therefore, the first-year language teacher is obliged to concentrate on the more formal aspects of the language (1996, p. 101).

At the same time, some scholars have pointed to a tendency, within T&I studies, to play down the need for linguistic excellence. According to Li (2001), linguistic competence has fallen victim to the increasing importance given to the wide variety of skills need (transferring the message from one language/culture to another and the command of concepts and terminology in specialized fields such as law, economics, science and technology, among others): "the role of language competence as a component in translation competence is played down unjustifiably" (Li, 2001, p. 344). He goes on to say that professional translators emphasize how important a full command of their working languages is and that his students recognize that they lack the necessary language skills.

The direction in which translators and interpreters should, or indeed do, work (L1<>L2) is something of a thorny issue. The traditional view, at least in the West, is that all work should always be carried out into the mother tongue, but professional practice in many fields of both translation and interpreting belies this ideal. For a wide range of reasons, ranging from lack of availability of other options, client trust in a specific translator/interpreter (and/or lack of knowledge of what the translation/interpreting process actually entails and the skills required to carry it out), to a specific professional’s in-depth knowledge of the specific subject and associated terminology and phraseology in both working languages, to name but a few, practitioners will fairly often be called on to translate/ interpret into their B language. Back in 1992, Pym stated "it is no longer enough to translate in one direction well, nor indeed to specialize in one particular field" (1992, p. 78). Other scholars not only recognize that it constitutes regular industry practice, but actually point out potential benefits of L2 translation. One such is Stewart (2000), who compares the disadvantages traditionally attributed to working into a foreign language (mainly the possible mistakes in L2 production) with the no less clear advantage of optimum understanding of all facets of the source text, with all its implicit and explicit referents and nuances. Possible limitations in the production of the target text in the foreign language may even have a silver lining, as long as it can be understood and conveys the meaning of the original in an acceptable manner, as it is less likely to be bound specifically to the culture of the translator/ interpreter’s place of origin (mainland Spain, for example, in Spanish, to the exclusion of many South and Central American usages and cultural references, or British English, some of whose usages and idioms are unlikely to be understandable for a broader English-speaking audience).

The call for L2 translations into English in Spain has been recorded by Beeby (1996), among others. This may be partly due to the undoubted importance of foreign tourism to the Spanish economy. According to figures provided by the World Tourism Organization (2015), Spain is currently ranked as the third biggest tourist destination in the world, both in terms of arrivals and income. Another factor driving L2 translation in Spain is the figure of sworn, or certified, translator, as regulated by the Spanish Ministry for Foreign Affairs. Successful candidates for this certification (obtained by public examination held by the Ministry) are appointed to translate both out of and into the foreign language in question. The corresponding examination tests translation in both directions, so they will need to produce texts in the foreign language, applying a wide range of linguistic and textual skills.

Regardless of the direction of the translation in question, it is clear that even a top-level command of the foreign language concerned will need to be contextualized in terms of usage in different types of text. No matter how correct the grammar, how wide the command of vocabulary, idioms and expressions, knowing when to deploy which variant among the wide range of options available in any language constitutes key know-how if appropriate transfer solutions are to be found in a given context or co-text. Thus, knowledge of textual conventions in both source and target languages and cultures plays a vital role in the correct understanding of source texts and the production of appropriate target texts. In the same vein, Cerezo Herrero (2013) highlights the idea that learning the foreign language through the use of different types of texts (newspaper articles, specialized material, talks, etc.) can help translation and interpreting trainees acquire the communicative competence included in translation competence models.

METHOD

Design

In this context, and in the light of all this data, as it has been explained in previous papers (Adams & Cruz García, 2016, 2017) the general aim of this study was to shed some light on current practice in foreign language classes within T&I faculties in Spain. In this case, the specific objective of this paper is to identify and describe how texts used in foreign language classes in Spanish Translation and Interpreting Faculties are exploited. The period studied precedes Spain’s universities’ entrance into the European Higher Education Area (2006-8). The aim is not to evaluate the validity or the teaching methodology of the participating lecturers, but rather to describe the different approaches used in order to draw conclusions as to the extent to which they cover the real, differentiated needs of these learners. The results are not presented in scale-form, but as total numbers of occurrences and percentages of use. This study uses a mixed quantitative and qualitative methodology.

Participants

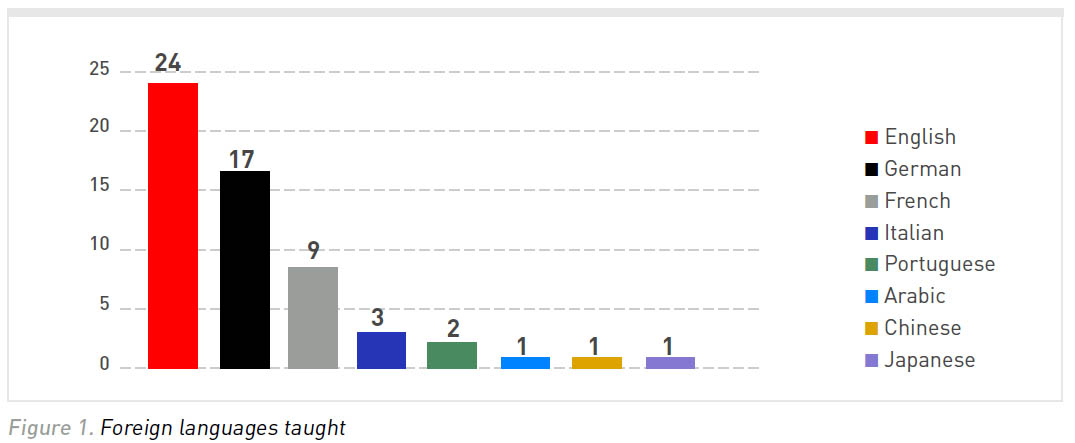

The questionnaire was sent to a pool of 238 lecturers of foreign languages, fifty-eight of whom responded to it. They taught, either as a B language or as a C language, English, German, French, Italian, Portuguese, Arabic, Chinese and Japanese at the Translation and Interpreting Faculties of 13 Spanish universities (Alicante, Autónoma de Barcelona, Europea de Madrid, Felipe II, Granada, Jaume I, Málaga, Pompeu Fabra, Salamanca, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Valladolid, Vic, and Vigo). They participated, on a voluntary, disinterested basis. So, no prior selection of participants was carried out other than their condition as foreign language trainers in the above-mentioned faculties. Although the final study sample constitutes 24.36% of the population, it was considered sufficient to shed light on the issues studied, at least in the case of the most commonly-taught foreign languages in Spain (English, French and German), Figure 1 details both the foreign languages taught by the lecturers who participated and the number of lecturers in each case:

As Figure 1 shows, the prevailing foreign languages in Translation and Interpreting studies in Spain are English, German and French, in that order. Languages such as Arabic, Chinese and Japanese are minority languages, to the extent that only one lecturer participated for each of them, while, at the other end of the scale, 25 English language trainers took part in our study.

In order to further break down responses by curricular year and B and C languages, respondents were asked to specify where their teaching lay in both respects.

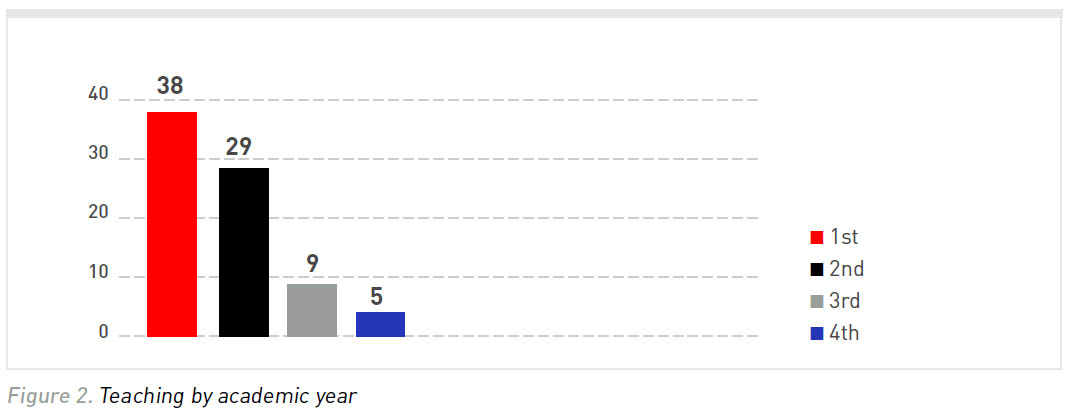

The breakdown of lecturers teaching in each academic year is given below:

The fact that the total number of occurrences (81) exceeds the 58 lecturers included in the survey can be explained by the fact that one lecturer will typically teach groups in different curricular years. The largest number of lecturers teaches in the first year of T&I studies; moreover, it is important to remember that some faculties only offer languages classes in the first year, others in the first two years, and so on.

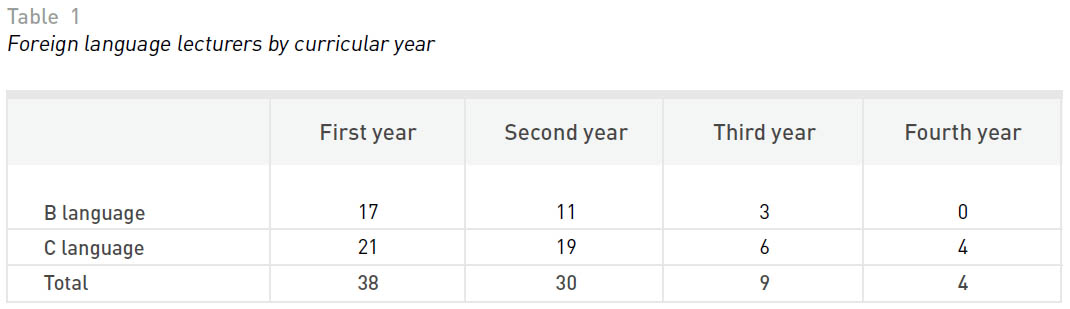

A breakdown by curricular year for the B and C language yields the following results:

Of the 38 lecturers who teach in the first year, 17 do so in the B language and 21 in the C; 10 lecturers teach both B and C languages. In subsequent curricular years, more C than B language teachers participated, which may also affect the overall final result, as students have a lesser command of the C language, which may lead trainers to resort to different methodologies.

Information Collection Instrument

In this study, the data was collected by means of a questionnaire created specifically in order to glean the type of information we wished to analyze. The questionnaire comprises closed, open and mixed questions. The responses obtained have enabled us to draw some conclusions as to how this subject is being tackled on the ground.

The questionnaire included twelve questions, each of which was aimed at eliciting specific information. The data given above as to the number of trainers by language, by academic year and broken down by B and/or C languages taught, are taken from the responses from the initial questions of the questionnaire that have enabled us to describe the participants. In this article, we will focus on the results of one of the open-ended questions included in the questionnaire.

Procedure

The questionnaire was sent by e-mail to 238 foreign (B and C) language trainers at the Translation and Interpreting Faculties whose websites provided contact details for said trainers. They were addressed by email and asked to fill in the questionnaire on a voluntary basis if they wished to contribute to the study. An explanatory message was sent to explain the aims and scope of the research. Not all the recipients completed and returned the questionnaire and, as has been specified, we received valid responses from 58 trainers. As the specific question whose results are presented here was open-ended, responses have subsequently been grouped together and classified in a set of general sections. The occurrences recorded in each section have provided us with quantitative results that have helped us to draw conclusions regarding the methodological tendencies recorded in the particular subject studied.

RESULTS

The question regarding the way in which texts are used in foreign language classes or more specifically, the specific aspects of the texts that are studied in these classes, was the ninth question of the questionnaire. Our results are of interest not only to look at the extent to which translation-related aspects are covered in foreign language classes, over and above traditional factors such as grammar and vocabulary. The exact wording of the question, as expressed in the questionnaire, is as follows: Al trabajar con un texto en clase ¿qué factores del texto se tratan? ¿Podría especificarlos? (ejemplos: gramática, vocabulario, etc.) [When working with texts in class, which aspects do you work on? Please specify (e.g. grammar, vocabulary, etc.)].

As this was an open-ended question, a wide range of heterogeneous answers were received, referring to many different levels and aspects of language, but they serve to give us an idea of the aspects considered most relevant in foreign language training for translators and interpreters in Spain. In order to facilitate the analysis of the data compiled in response to this question, the responses have been classified into the following groups of factors:

-

Morpho-syntactic elements, including grammar, syntax and morphology

-

Lexical-semantic factors, covering vocabulary, lexis, idiomatic expressions, phraseology, idioms, and collocations

-

Phonetic-phonological elements, including phonetics and pronunciation

-

Pragmatic aspects, such as pragmatics, communicative intention, functional aspects, context, addressee(s) and communicative and implicit factors

-

Cultural questions, covering cultural aspects, culture and intercultural factors

-

Text type related matters, including conventions, typology, register, style, genres and stylistic resources

-

Textual/discursive elements, such as coherence, cohesion, structure, organization, discourse markers, macrostructure and intertextuality

-

Semiotics

-

Translation-related elements, such as translation per se, the identification of translation problems, contrastive characteristics and languages in contrast.

Apart from the aspects included in these classifications, some respondents mentioned other types of elements (specifically, 17) concerning classroom methodology (including comprehension, oral reproduction, rewriting, transformation, synthesizing and drafting), which have not been included in our analysis.

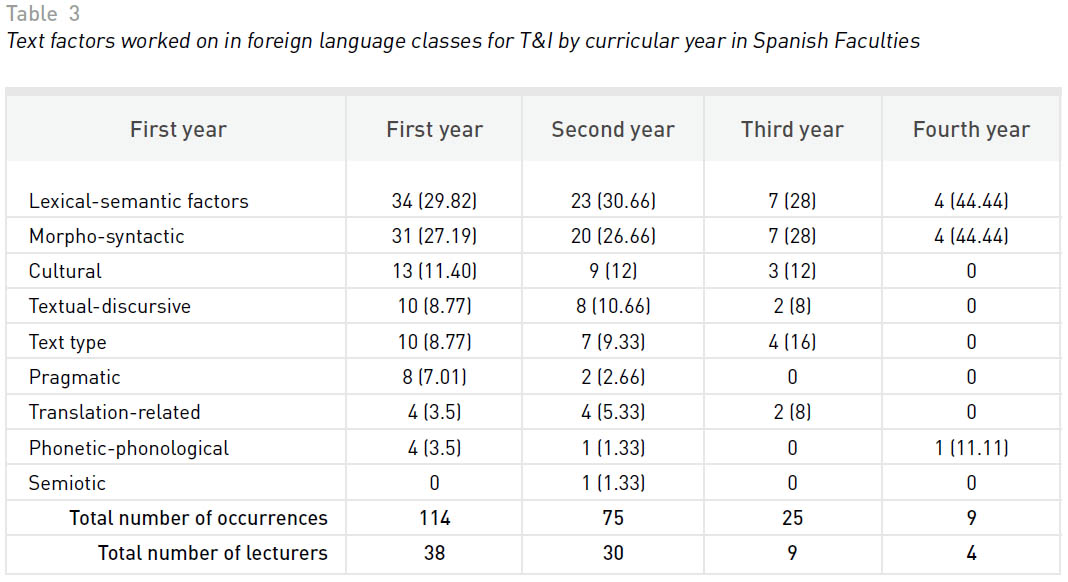

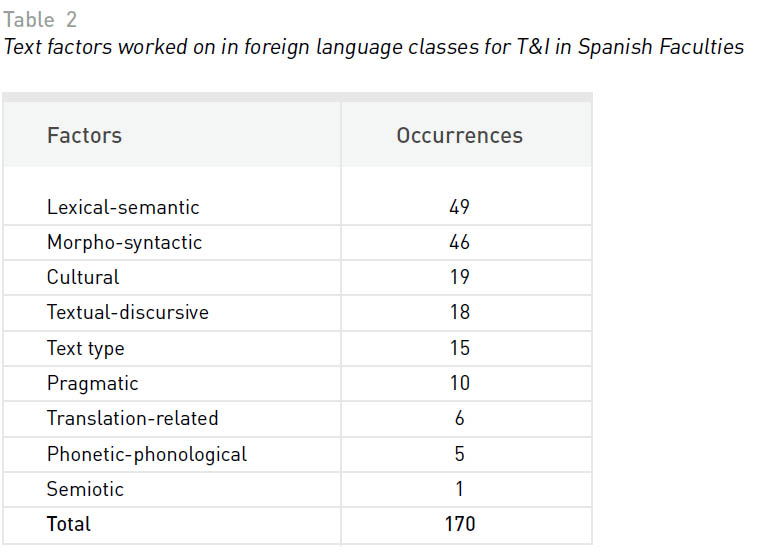

The following table presents the frequency with which the factors described above featured in responses.

As we can see from the table, lexical-semantic and morpho-syntactic aspects are those featuring most heavily, followed at a considerable distance by cultural and textual-discursive questions and those related to text type. Table 3 shows the breakdown by curricular year of said factors. The first figure in each column represents the total number of occurrences and the one in brackets represents the percentage value.

As we can see from Table 3, first, second and third year classes present similar results regarding lexical-semantic factors, morpho-syntactic, cultural and textual-discursive characteristics. Text type-related features are most frequently dealt with in the third year. Phonetics is not mentioned in the third year, and fourth-year studies are almost entirely based on lexical-semantic and morpho- syntactic aspects.

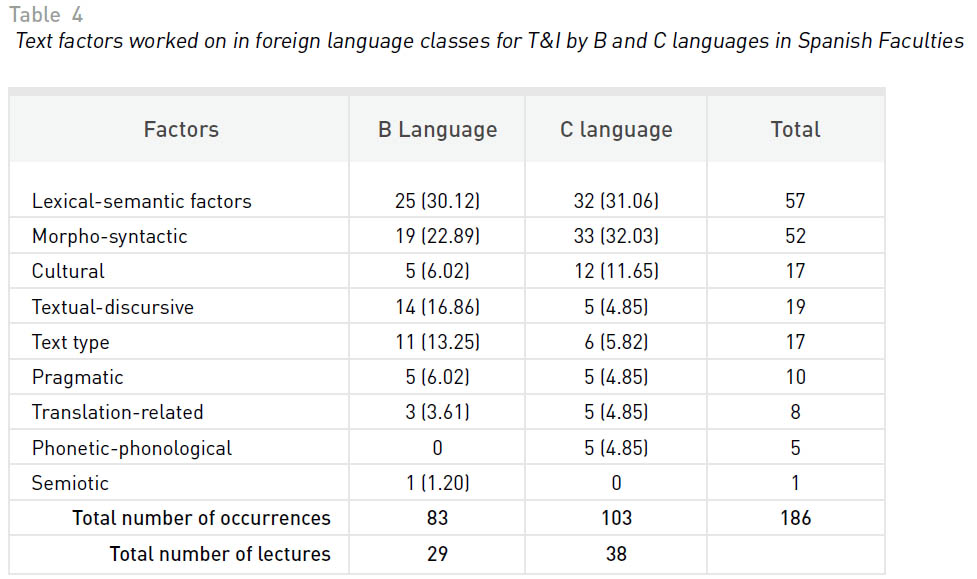

The following breakdown of the total figures of factors addressed looks at the factors by B and C language.

As Table 4 shows, morpho-syntactic and cultural aspects receive less attention in B classes than in C languages (although both categories are considered very important in both cases). This is offset by the fact that textual-discursive, pragmatic and above all text type aspects receive more attention in the B language classes than in C language classes. Phonetic and phonological aspects were only considered in C language classes.

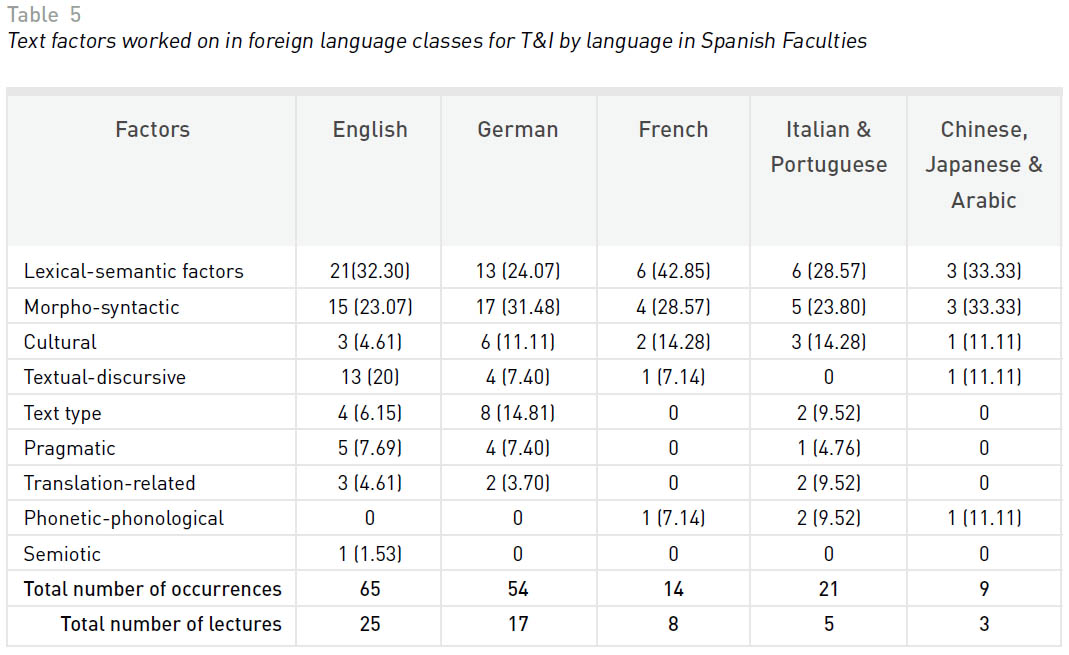

As we can see in Table 5, less importance is attributed to cultural aspects in English classes in this context than in any of the other languages. At the same time, it is in English classes that textual- discursive factors are of most interest. In turn, German classes tend to favour the text-type approach to a greater extent than other languages. Phonetic and phonological aspects are not covered in English or German.

DISCUSSION

Given that professional translators and interpreters are in continuous contact with a wide range of text types in their daily work, we believe, following Cerezo Herrero (2013), that classroom practices for trainees in this field should be largely based on the study of a wide variety of texts. There can be no doubt that the aspects mentioned by the trainers who responded to our questionnaire are relevant in foreign language learning. It might be worth flagging up those aspects that warrant greater attention in this specific context, or those that point to the specific training needs of trainee translators and interpreters.

If we bear in mind that the dominant foreign language learnt in the world is English, and without wishing in any way to detract from the importance of other languages, it comes as no surprise that the highest number of participants in this study teach English, followed by German and French. Although it might, a priori, appear that the scant numbers of language trainers in Italian, Portuguese, Arabic, Chinese and Japanese, who participated in the study could undermine the representativeness of their answers, the fact that their responses were similar to those of trainers in other foreign languages leads us to posit that the methodology they use may actually be broadly in line with that used in the classes of the "majority" languages, despite the specific, differentiated nature and characteristics of some of these languages, particularly Arabic, Chinese, and Japanese.

As we can see, the largest number of lecturers teach in the first year of T&I studies. This may be due to the fact that some faculties only offer languages classes in the first year, others in the first two years, and so on. Few Spanish faculties offer foreign language classes in the final curricular years.

Table 2 in the results section shows a prevalent interest in the study of lexical-semantic and morpho-syntactic aspects when specific texts are used in class, but responses to question 9 of the questionnaire show slightly different tendencies, based on a number of variables:

-

The curricular year (1st, 2nd, 3rd or 4th) in which the language in question is taught

-

Whether the language in question constitutes the B or C language

-

The language itself (English, German, French, Italian, Portuguese, Chinese, Japanese or Arabic)

Although across all the curricular years, from the first to the fourth year, lexical-semantic and morpho-syntactic factors (Table 3) are given the most attention, text types and translation-related aspects feature to a greater extent in the third year than in previous years. Similar results might be expected in the fourth (and final) year, although these results indicate that it is once again lexical- semantic and morpho-syntactic factors that receive most attention and one respondent mentioned phonetic-phonological matters. Moreover, we should also bear in mind that these trainers (of whom there are four) teach C languages, of which students can be assumed to have a lesser grasp. However, as only four fourth-year trainers have responded to the questionnaire, this result is far from conclusive.

In general, these results can be construed as reflecting the greater need for consolidation in lexical acquisition and grammar knowledge and use in the earlier years of their degree courses, hence explaining why text-type and other specifically translation-related issues are only introduced in later curricular years. This finding concurs with the need for students first to acquire a command of formal correctness in order subsequently to acquire textual competence, as posited by Ruzicka Kenfel (2003).

As far as the variable of B or C language teaching is concerned, Table 4 shows that greater attention is paid to morpho-syntactic and cultural aspects in C than in B language classes. By contrast, textual-discursive and text type aspects are incorporated more in B language classes. As we could read above, students have a lesser command of their C language, which would explain the extent to which grammatical and lexical aspects feature so highly in these language classes. It is also here that we see phonetic and phonological factors dealt with, presumably for the reason already proffered.

The results regarding the variable of the specific language studied (Table 5) reveal that cultural aspects (one of Brehm Cripps & Hurtado Albir’s [1999] main objectives in foreign language classes for trainee translators) receive the least attention in English classes in this context. One reason for this may lie in the fact that students are more familiar with Anglo-Saxon culture, as it has for a long time been the first foreign language taught in Spanish schools, from primary education onwards. For this same reason, it seems obvious that it is in English that students have a better command of the foreign language and that this enables them to tackle the textual-discursive aspects. It is also noteworthy that phonetic and phonological aspects are not covered in either English or German, although this may be explained by the difficulty that French, Italian and Portuguese phonetics may constitute for Spanish students, despite being romance languages that these same students can easily understand in their written form.

It is interesting to note that while scholars like Beeby (1996) and Li (2001), already mentioned, are concerned that training in linguistic competence has fallen victim to a preference for aspects relating to translation-related tasks, the results from this study show that grammar and vocabulary are still the main focus of language training in this educational context.

Although some tendencies can be observed in the results obtained, we must be aware of the fact that other variables come into play that may lead trainers to put texts to different uses within their foreign language classes of which circumstances, resources and their own specialized training are but three.

All of the above factors have to be planned and set out at the beginning of the semester or year in the teaching programme. Bearing in mind that classes will sometimes include a large number of students of widely varying levels of competence and experience (including travel, professional work and contact with a foreign culture, amongst other factors), not to mention the inevitable differences in levels of self-esteem, motivation and commitment to the requirements of the degree, it comes as no surprise that reality in the classroom rarely coincides with ideal notions of teaching situations. Lecturers have to be realistic when determining what is going to be covered and students need to be mature and get fully involved if they wish to make the most of the experience.

Perhaps the aspect in which the teaching of foreign languages for translation and interpreting can most clearly be distinguished from that carried out in other settings is in the use of different types of text as material for study, as pointed out by Berenguer (1996) and Li (2001), mentioned above. While students of languages for specific purposes (such as medicine, engineering, computer science, law, etc.) focus on texts drawn from their specialist fields, translation and interpreting students have to familiarize themselves with texts drawn from a wide range of subject matters and registers, from the most informal type of texts used in daily life to the most formal and highly specialized.

Moreover, as translation does not consist of the transfer of words or decontextualized expressions from one language to another, translator assignments do not entail the translation of words or random phrases, but rather whole texts with a specific function. These texts are produced within a specific professional field and have a set of norms or conventions of their own, together with specific language use, style and vocabulary. The student’s first task, then, will be to learn about what these texts are like, to become familiar with a wide range of different texts and to learn to recognize the differences and similarities existing between texts that fulfil the same function in two different cultures. This will require a detailed analysis of the formal aspects of the text, its conventions and specific characteristics, as a necessary prerequisite to the translation process.

Specifically, classes serve to present a selection of texts in the target culture that clearly illustrate the function and formal aspects of different text types. In other words, if we take, for example, a magazine advertisement, it would be important first to analyze the function of the text as a whole (to persuade the reader to buy a product, to promote a new product or service or to sell a brand image, among others). Subsequently, the focus could lie on how said function is achieved, i.e. the linguistic elements used to the specific end in question, and those that are used most frequently. These could include the types of verbs and verb tenses and modes; syntactical structures, vocabulary and phraseology. Of similar importance will be the image used (and attention needs to be paid to use of colour, perspective and what is actually represented). Once these elements have been analyzed, the connotations implied by the elements used, and by the specific combination thereof must also be taken into consideration. In short, all relevant semiotic and pragmatic factors will be analyzed, always in line with their relevance and meaning in the target culture. A further step entails comparing an advertisement in the source language with one for the same product, or a similar one, in the target language. This will enable students to see the extent to which the text types coincide and/or use different resources to achieve the same effect and, at the same time, reflect different aspects of each of the cultures in question.

Examples of other types of text that lend themselves to this type of analysis include the following categories, each accompanied by just a few examples: legal texts (a leasehold contract for a flat), scientific texts (prescriptions or medical prospectuses or abstracts of scientific articles), official administrative texts (birth certificates, degree certificates or transcripts of records), informative administrative texts (driving license or passport application forms), instructions (white goods’ instruction manuals, computer equipment and software user guides), and literary texts (short stories, novels, poems).

This list is by no means exhaustive. There are of course many other examples for each text type given, and a number of other categories could also be established, all of which have their own particular style and textual conventions that can be worked on in class. They all have an equivalent in the source language culture and all present specific problems and challenges when mooting a potential translation.

Text type analysis will help them to contemplate tackling long, authentic, specialized texts, providing a sound basis on which to build their professional future. This specific need makes applied translation-related foreign language learning clearly distinguishable from other types of L2 learning and teaching for general uses. This system promotes the search for and analysis of parallel texts, both in the foreign language and in the mother tongue. It can also help to encourage a view of translation as a practice that is grounded in the real world, in professional practice, rather than an abstract or literary concept serving academic ends. Students will thus be confronted with the reality of translating medical, legal, tourist and scientific texts, among others, and will consequently be better placed to make an informed decision about what the translation profession actually entails on a daily basis, moving them away from a more romantic conception of the translator working in an ivory tower on novels or poetry, for example.

In short, the aim here is that translation and interpreting students should be introduced to the realities of the profession(s) from the outset and trainers should leave no stone unturned in preparing students to be able to fulfil their future role as a translator and/or interpreter.

We are fully aware of the fact that this initial study needs to be broadened in scope if more conclusive results are to be obtained; that the number of participating trainers in some languages is insufficient and that this may have affected the final result. This initial approximation to the reality in foreign language classrooms in Translation and Interpreting faculties before Spanish universities entered the European Higher Education Area requires updating in order to identify how things may have changed now that the new system has not only been introduced, but new curricula, procedures and teaching practices have undergone an initial process of consolidation. Further study of this kind would constitute an opportunity to see what progress has been made. It could also be relevant to include a variable that was not observed in this study, namely the specific training and qualifications of those lecturers who teach foreign languages in T&I Faculties, in order to verify whether their own training, be it in philology or translation and interpreting, plays a part in the methodology they apply in the classroom.

REFERENCES

Adams, H. & Cruz García, L. (2016). Towards LSP (I) – Language Teaching for Future Interpreters. En Actas V Congreso Sociedad Española de Lenguas Modernas (pp. 29-40). Sevilla: Bienza. [ Links ]

Adams, H. & Cruz García, L. (2017). Towards LSP (II) – Language Teaching for Future Interpreters: Graduate Profiles (Vol. 2). En C. Vargas-Sierra (Ed.), Professional and Academic Discourse: an Interdisciplinary Perspective (pp. 346-353). Recuperado de https://easychair.org/publications/paper/mj [ Links ]

Beeby, A. (1996). Teaching Translation from Spanish to English. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press. [ Links ]

Beeby, A. (2004). Language Learning for Translators: Designing a Syllabus. In K. Malmkjaer (Ed.), Translation in Undergraduate Degree Programmes (pp. 39-65). Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins. [ Links ]

Berenguer, L. (1996). Didáctica de segundas lenguas en los estudios de traducción. En A. Hurtado Albir (Ed.), La enseñanza de la traducción (pp. 9-29). Castellón: Universtitat Jaume I. [ Links ]

Brehm Cripps, J. (1996). La enseñanza de lengua B. En A. Hurtado Albir (Ed.), La enseñanza de la traducción (pp. 175-181). Castellón: Universtitat Jaume I. [ Links ]

Brehm Cripps, J. & Hurtado Albir, A. (1999). La enseñanza de lenguas en la formación de traductores: la primera lengua extranjera. En A. Hurtado Albir (Ed.), Enseñar a traducir. Metodología en la formación de traductores e intérpretes (pp. 59-71). Madrid: Edelsa Grupo Didascalia. [ Links ]

Cerezo Herrero, E. (2013). La enseñanza del inglés como lengua B en la formación de traductores e intérpretes en España: la comprensión oral para la interpretación (Tesis doctoral). Universidad de Valencia, [ Links ] España.

Li, D. (2001). Language Teaching in Translator Training. Babel, 47(4), 343-354. doi: https://doi.org/10.1075/babel.47.4.05li [ Links ]

Pym, A. (1992). In Search of a New Rationale for the Prose Translation Class at University Level. Interface: Journal of Applied Linguistics, 6(2), 73-82. [ Links ]

Ruzicka Kenfel, V. (2003). Lengua alemana en traducción/interpretación: un concepto particular de la enseñanza de alemán como lengua extranjera. BABEL-AFIAL, 12, 5-29. Recuperado de https://goo.gl/VRPTcT [ Links ]

Stewart, D. (2000). Poor Relations and Black Sheep in Translation Studies. Target, 12(2), 205-225. doi: https://doi.org/10.1075/target.12.2.02ste [ Links ]

World Tourism Organization (2015). UNWTO Annual Report 2015. Recuperado de https://goo.gl/yQN7iu [ Links ]

*E-mail: laura.cruz@ulpgc.es

Recibido: 06-10-17

Revisado: 20-11-17

Aceptado: 01-12-17

Publicado: 18-12-17