Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista Peruana de Ginecología y Obstetricia

versión On-line ISSN 2304-5132

Rev. peru. ginecol. obstet. vol.67 no.2 Lima abr./jun. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.31403/rpgo.v67i2332

Section bioethics in gynecology and obstetrics

Bioethics in the practice of colposcopy

1. Human Papilloma Virus Unit of the National Cancer Institute of the USA (NCI). Member of the Board of Directors of the International Human Papilloma Virus Society (IPVS). Former Member of the Board of Directors of the American Society for Cervical Pathology and Colposcopy (ASCCP). Member of the Education Committee of the International Federation of Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (IFCPC).

2. Associate Editor of The Peruvian Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. Former President of the Peruvian Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Honorary Member of six Obstetrics and Gynecology Societies of Latin America. Member of the Committee of Ethical and Deontological Surveillance Regional Council III of the Medical College of Peru. Latin American Master of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Fellow of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

3. President of the Peruvian Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology 20212022, Fellow American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Permanent Advisor of the Advisory Council of the Hipolito Unanue Institute Foundation. Gynecology and Obstetrics

The objective of this presentation is to encourage gynecology and obstetrics specialists to reflect on the ethical management of all their cases and clinical procedures, ensuring that their professional performance is in line with scientific knowledge, evidencebased medicine and respect for the principles of bioethics. We present the case of a 20-year-old patient who underwent several cervical cancer screening and diagnostic tests that triggered a surgical recommendation. A clinical and ethical analysis of the case is made, and recommendations are given for appropriate management guided by evidence and national and international recommendations.

Key words: Ethics; medical; Bioethics; Colposcopy

Introducción

This is the fourth publication on ethics published by the Peruvian Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics (RPGO) in the last 12 years, in keeping with the importance given to this discipline in the work of physicians, particularly obstetricians and gynecologists1-3. Due to the importance assigned to the subject, the Peruvian Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology (SPOG) held a contest in 2009, together with the Peruvian Medical College (CMP), in which different topics of ethics in sexual and reproductive health were highlighted4. In the same year, it was part of a Workshop on Values Clarification, in Trinidad, Bolivia5.

Although it is true that scientific knowledge, attitudes and skills are transcendent in the training of physicians, the ethical and bioethical component also plays an important role and is transversal to all disciplines of medical science to ensure the integral performance of the professional. The development of science and technology, in general, has expanded the role of medicine and physicians, but the technological progress of mankind has not gone hand in hand with ethical reflection, so that eventually the sustainability of human life and that of other living beings has been put at serious risk6.

Since the ancient times of medicine, it is said that Hippocrates coined the idea of "first do no harm" (primum non noscere), in the same way that he recognized privacy and professional secrecy as a necessity in the doctor-patient relationship3. This paternalistic way of practicing medicine was maintained for centuries, until the mid-twentieth century when ideologies began to change. It was after the Second World War, following the Nuremberg trial (1947), that the Nuremberg Code (1949) was created, which incorporated the right of individuals to autonomy, to decide about diagnostic, therapeutic and experimental means7. In other words, to informed consent.

Later, in 1964, the World Medical Association drew up the first version of the Declaration of Helsinki, which recognizes the right of individuals to qualified medical care and the importance of ethics committees8. It was the medical pathologist Potter who initiated a turn in the ethical doctrine through his publication "Bioethics the Science of Survival"9. The Congress of the United States of America, faced with abuses in experimental research in the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, carried out from 1932 to 1972, created a special committee which, in 1979, signed the Belmont Report (named after the place where it was signed), in which three principles of bioethics are recognized: Beneficence (maximum benefit with minimum risk), Respect for persons (self-determination, autonomy and informed consent) and Justice (equitable selection of the participant)10, to which was added the following year the principle of Non-Maleficence (do no harm), in the publication of Beauchamp and Childress11. This is how the principlism of bioethics is constructed in the USA, which has not been exempt from criticism, so that more principles have been added, such as solidarity and others.

As we can see, the ethical framework of medical paternalism has changed to an ethical framework based on the rights of individuals, where the principles of bioethics, which are not consistent with human rights, have their place. Within this framework, the World Conference on Population and Development, held in 1994 in Cairo, recognized the provision of health care based on human rights (HR) and recognized Sexual and Reproductive Rights (SRHR)12, which were confirmed in Beijing, the following year, during the World Conference on Women13. The SRHR have been exquisitely and extensively developed by Dr. Rebeca Cook and collaborators14.

In our country, the General Health Law of 1997 recognizes the individual's right to autonomy, as well as medical confidentiality, conscientious objection and some other items related to sexual and reproductive health15. Similarly, medical and non-medical institutions have developed activities on the recognition of sexual and reproductive rights and specifically on their ethical aspects16.

In the context of this background and in the knowledge of the deep moral crisis we are living is that the SPOG, and specifically the Editorial Committee of the RPGO, consistent with the doctrinal and theoretical aspects of medical ethics, has considered incorporating a Section of Ethics and Bioethics in the practice of our specialty and we start with the edition of this article, which develops the reflection on the practice of colposcopy that requires not only the medical professional with sufficient training in the structure and pathology of the cervix, mainly in the diagnosis of cancer. It also requires professional performance with strict adherence to bioethical conduct, taking care that their practice is not supplanted by unqualified professionals and is conducted on the basis of the provisions of the Code of Ethics and Deontology of the Peruvian Medical Association17 and the ethical recommendations of the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics FIGO18).

Clinical description

The case is of a 20-year-old woman, G0P0, with sexual debut at the age of 19 years, with only one sexual partner. She attended a gynecologic evaluation referring pruritus in the external genitalia. On gynecological examination, abundant whitish leucorrhea and erythema were found at the level of the external genitalia. The vagina and cervix had no evident alterations. A cervical smear was taken for cytological examination (Papanicolaou), the result of which was ASCUS, so she was indicated to require colposcopy. On colposcopic examination, a visible squamo-columnar junction with faint whitish epithelium was found. A biopsy of the cervix was taken, which was reported to have 'areas suggestive of mild dysplasia'. She was instructed to undergo cone LEEP. The patient consulted for a second opinion.

The case is of a 20-year-old woman, G0P0, with sexual debut at the age of 19 years, with only one sexual partner. She attended a gynecologic evaluation referring pruritus in the external genitalia. On gynecological examination, abundant whitish leucorrhea and erythema were found at the level of the external genitalia. The vagina and cervix had no evident alterations. A cervical smear was taken for cytological examination (Papanicolaou), the result of which was ASCUS, so she was indicated to require colposcopy. On colposcopic examination, a visible squamo-columnar junction with faint whitish epithelium was found. A biopsy of the cervix was taken, which was reported to have 'areas suggestive of mild dysplasia'. She was instructed to undergo cone LEEP. The patient consulted for a second opinion.

Case discussion

Screening

The patient is quite young, 20 years old, so it is not advisable to start screening for cervical cancer. The guidelines of the Peruvian Ministry of Health19 indicate that screening should begin at 25 years of age, using cervical cytology. For its part, the World Health Organization indicates that cervical cancer screening should begin at the age of 30 years because this neoplasm is more frequent at that age20. In the United States of America, it is contraindicated to start screening before the age of 21 years21. Therefore, the patient described in this article should not have had cervical cytology for cervical cancer screening.

The main reasons for contraindicating cervical cancer screening in young women are:

Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is extremely common at young ages after initiation of sexual life. Although HPV is necessary for the development of cervical cancer, most infections in young people are transient22, with more than 80% of infections clearing naturally within 12 to 18 months.

Transient HPV infections may cause minor changes in the epithelial cells of the cervix, which may be reported as ASCUS or lowgrade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LSIL); but these changes are not significant and will disappear once the infection is cleared by the young woman's natural immunity23.

Truly precancerous lesions of the cervix and invasive cancer are extremely rare in women under 30 years of age, which is why the recommendations in Peru and internationally do not indicate screening until the woman reaches 25 or 30 years of age19-21.

Screening for cervical cancer in young women only creates confusion and distress in patients, has no real benefit and, on the contrary, exposes the patient to unnecessary medical procedures that are harmful to the reproductive health of the young woman.

Diagnostic procedures

Regarding the management of the screening test result, the patient has a cytology of ASCUS, which means that there are atypical cells or cells with minor alterations that the pathologist cannot determine their actual significance. As explained above, transient HPV infections are very common in young women and are commonly associated with minor cytologic changes that do not have premalignant potential. The ALTS study24 conducted by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) in the USA has shown that only a minority of patients with ASCUS have HPV infection; the vast majority of times, ASCUS is associated with other causes without malignant potential such as lower genital tract infections, hormonal changes, among others.

Something very important to consider is the training of the pathologist who reads the cytology or cervical biopsy slides. It is commonly assumed that all pathologists have adequate training to evaluate Pap or biopsy specimens, but multiple studies have shown that there is high variability in pathologists' diagnoses. One way to assess whether the pathologist requires special training is by measuring the percentage of specimens he or she reports as ASCUS; it is accepted that only 5% to 10% of cytology specimens should have a diagnosis of ASCUS. If the pathologist reports ASCUS in a higher percentage of specimens it can be considered that he/ she should have additional training and/or specialized supervision.

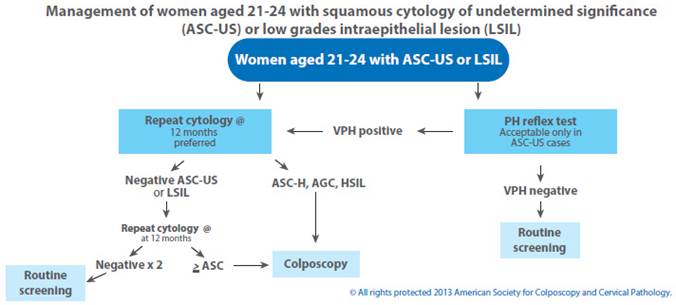

Following the evaluation of the patient's results, we find that even though she should not have had cervical cancer screening due to her age, we are in the need to act on the reported ASCUS result. The recommendation of the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP)25 is that a patient with a cytologic result of ASCUS should be rescreened in 12 months. We should be clear that no additional procedure is indicated in a patient with ASCUS cytology. The colposcopic evaluation indicated for the patient described in this article is not recommended by any existing national or international management guidelines (See Figure 1).

It is important to highlight that colposcopic evaluation is not recommended in patients with inflammatory processes of the lower genital tract. The reason is that the inflammatory process is usually associated with benign reactive changes in the cervical epithelium, such as squamous metaplasia, which can be observed as faint acetowhite epithelium, which the inexperienced colposcopist may confuse with epithelium with premalignant changes, and trigger unnecessary biopsies.

The histopathological study of the biopsy was reported as "areas suggestive of mild dysplasia". It is important to emphasize again that the experience of the pathologist is very important in the reading of cervical biopsies; and there is considerable discrepancy in the reading performed by different pathologists. The report of "areas suggestive of mild dysplasia" indicates that the pathologist is unsure of the diagnosis and should compel us to request a review of the pathology slide by a pathologist with experience in evaluating cervical specimens.

Assuming that the review of the slides confirms that the patient has mild dysplasia, she does not require any type of surgical intervention. The MINSA guidelines clearly indicate that a patient with CIN 1 (mild dysplasia) should not receive treatment and a repeat cytology should be performed at 12 months. A similar recommendation is found in the US ASCCP guidelines.

Treatment

The LEEP cone recommended to the patient is totally contraindicated, not only because CIN1 or mild dysplasia should not be treated, but also because LEEP loop cone excision has effects on a woman's obstetric future, especially when performed in young women. Already almost 20 years ago it was described that patients undergoing cone LEEP have a higher risk of preterm delivery26. More recently Sadler and collaborators27 also reported that the risk of premature rupture of membranes is increased in patients who have undergone cone LEEP. Very relevant to the case described in this article is the study by Chevreau28 who reports that the risk of obstetric complications is even higher if the LEEP cone is performed when the woman is less than 25 years of age.

Bioethical discussion

The bioethical principle of beneficence indicates that we should act in the best interest of our patients, promoting their interests and suppressing any prejudice (maximum benefit with minimum risk). In the case of the patient described in this article, this ethical principle, which is fundamental in the practice of medicine, has not been complied with. The patient has not had the evaluations she should have had at her age and excessive action has been taken without any benefit to her. The patient was exposed to invasive tests (colposcopy and biopsy) that are unnecessary for the patient's age and clinical picture, exposing her to unnecessary risks, which clearly violates the principle of non-maleficence. Although the patient was not finally submitted to cone LEEP because she went to another physician for a second opinion, such surgery was indicated without considering the patient's benefit and, more importantly, without considering the obstetric complications resulting from cone excision using LEEP loop, affecting the patient's obstetric future.

If we consult the Code of Ethics and Deontology of the Peruvian Medical Association(17), in this case the Declaration of Principles 3, the principles and ethical values in Medicine, has been violated, which reads as follows:

Ethical principles and values are social and personal aspirations. As far as society is concerned, these highest aspirations are solidarity, freedom and justice, and as far as the individual is con-cerned, respect for dignity, autonomy and integrity. In the professional practice of medicine, these aspirations are realized through the precepts of beneficence -which consists of seeking the good of the patient- and non-maleficence -which consists of preventing any form of harm or injury from occurring.

And articles 1, 9, 55, 63 clause d, of the same code, which literally say:

Art 1.- It is the duty of the physician to perform his profession competently, having, for this purpose, to continuously improve his knowledge, skills and attitudes and to practice his profession integrating himself into the community, with full respect for the socio-cultural diversity of the country.

Art 9.- The physician shall practice medicine on a scientific basis and shall be guided by validated medical procedures.

Art 55.- In patients who require diagnostic or therapeutic procedures that involve risks greater than the minimum, the physician must request written informed consent, by means of which they are informed of what they consist of, as well as the possible alternatives, the probable duration, the limits of confidentiality, the benefit/risk and benefit/cost ratio.

Art 63.- The physician shall respect and seek the most appropriate means to ensure respect for the patient's rights, or their reestablishment in case they have been violated. The patient has the right to:

(d) Obtain all information that is truthful, timely, understandable, about his diagnosis, treatment and prognosis.

Key clinical messages

Cervical cancer screening should not be initiated in women under 25 years of age as there is no benefit for the patient.

HPV infection is very common in young women and the vast majority do not require any intervention because in most women the infection is cleared naturally by the immune system.

Patients with ASCUS should not have colposcopy and/or biopsy. International recommendations indicate that they should be followed up in 12 months.

Colposcopy should not be performed when there are inflammatory processes of the lower genital tract since the inflammatory process triggers benign changes that may confuse the colposcopist.

LEEP should not be performed in young women or in women who wish to have children due to the obstetric implications of such surgery. Premalignant lesions can be treated with ablative methods that do not alter the anatomy or function of the cervix.

Ethical recommendations

1. To develop the teaching of Ethics and Bioethics as a transversal discipline in the medical profession.

2. To strengthen moral values in the medical professional.

3. To provide correct and complete information to the users of the gynecological practice.

4. Empowering women users of gynecological services to make their own decisions.

5. Adequately train gynecology and obstetrics medical personnel in the practice of colposcopy.

6. To provide colposcopy services with strict adherence to bioethical principles.

REFERENCES

1. Távara Orozco L. Symposium: Bioética en salud sexual y reproductiva. Rev Peru Ginecol Obstet. 2009;55:228-9. [ Links ]

2. Távara Orozco L. Introducción al Simposio Bioética y atención de la salud sexual y reproductiva. Rev Peru Ginecol Obstet. 2017;63(4):553-4. [ Links ]

3. Távara Orozco L, Mendoza Fernández A, Rondón Rondón M, Benavides Zúñiga A, Aliaga Viera E. Simposio Ética clínica en la práctica ginecobstétrica. Rev Peru Ginecol Obstet. 2020;66(2). https://doi.org/10.31403/rpgo.v66i2250 [ Links ]

4. Colegio Médico del Perú. Bioética y salud sexual y reproductiva. Relato final. Lima: CMP, marzo 2009. [ Links ]

5. FLASOG. Comité de Derechos Sexuales y Reproductivos. Relato Final del Taller Marco Bioético y Clarificación de Valores en la prestación de servicios de salud sexual y reproductiva. Trinidad, Bolivia: FLASOG, septiembre 2009. [ Links ]

6. Mendoza A. La responsabilidad ética del médico. En: Simposio Ética clínica en la práctica ginecobstétrica. Rev Peru Ginecol Obstet. 2020;66(2). https://doi.org/10.31403/rpgo. v66i2250 [ Links ]

7. The Nuremberg Code 1947. En: Mitscherlich A, Mielke F. Doctors of infamy: the story of the Nazi medical crimes. New York: Schuman, 1949. [ Links ]

8. Manzini J. Declaración de Helsinki: Principios éticos para la investigación médica sobre sujetos humanos. Acta Bioethica. 2000;6(2):320-34. [ Links ]

9. Potter VR. Bioethics the science of survival. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine. New York, 1970. [ Links ]

10. HHS.gov. The Belmont Report. Ethical principles and guidelines for the protection of human subjects of research. Office for Human Research Protections. USA April 18, 1979. https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/belmont- report/read-the-belmont-report/index.html [ Links ]

11. Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principios de ética biomédica. Barcelona: Masson, 1999. [ Links ]

12. UNFPA. International Conference on Population and Development. UNO: Population Fund, New York, USA 1995. [ Links ]

13. UNFPA. International Conference on Women, Beijing. UNO: Population Fund, New York, USA, 1995. [ Links ]

14. Cook RJ, Dickens BM, Fathalla MF. Salud Reproductiva y Derechos Humanos, 2a Ed, traducida al español. Bogotá-Colombia: Profamilia 2005:605. [ Links ]

15. Ley General de Salud. Lima, Perú 1997. [ Links ]

16. FLASOG. Declaración sobre los derechos sexuales y reproductivos. Congreso Latinoamericano de Ginecología y Obstetricia. Santa Cruz de la Sierra-Bolivia: Comité de Derechos Sexuales y Reproductivos 2002. [ Links ]

17. Colegio Médico del Perú. Consejo Nacional. Código de ética 2007. [ Links ]

18. FIGO. Ethical issues in Obstetrics ang Gynecology by the FIGO Committee for the study of ethical aspects of human reproductive and women's health. London 2009. [ Links ]

19. Directiva Sanitaria Nº 0RS-MINSA-2019-DGIESP. Directiva sanitaria para la Prevención del Cáncer de Cuello Uterino mediante la Detección Temprana y Tratamiento de Lesiones Pre-Malignas incluyendo Carcinoma In-Situ. Ministerio de Salud de Perú (MINSA), 2019. [ Links ]

20. World Health Organization. ( 2020) . Global strategy to accelerate the elimination of cervical cancer as a public health problem. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/ iris/handle/10665/336583 [ Links ]

21. Screening for Cervical Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2018 Aug 21;320(7):674-686. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.10897 [ Links ]

22. Schiffman M, Castle PE, Jeronimo J, Rodiguez AC, Wacholder W. Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. Lancet 2007 Sep 8;370(9590):890-907. [ Links ]

23. Moscicki AB, Shiboski S, Hills NK, et al. Regression of lowgrade squamous intra-epithelial lesions in young women. Lancet 2004;364: 1678-83. [ Links ]

24. Mark Schiffman , Diane Solomon. Findings to date from the ASCUS-LSIL Triage Study (ALTS). Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003 Aug;127(8):946-9. doi: 10.5858/2003-127-946-FTDFTA [ Links ]

25. Wright TC Jr. The new ASCCP colposcopy standards. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2017 Oct;21(4):215. [ Links ]

26. Crane JM. Pregnancy outcome after loop electrosurgical excision procedure: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol 2003 Nov;102(5 Pt 1):1058-62. [ Links ]

27. Sadler L, Saftlas A, Wang W, Exeter M, Whittaker J, McCowan L. Treatment for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and risk of preterm delivery. JAMA. 2004 May 5;291(17):2100-6. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.17.2100. PMID: 15126438. [ Links ]

28. Chevreau J, Mercuzot A, Foulon A, et al. Impact of age at conization on obstetrical outcome: a case-control study. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2017;21(2):97-101. doi:10.1097/ LGT.0000000000000293 [ Links ]

Received: June 07, 2021; Accepted: June 10, 2021

texto en

texto en