Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Revista Peruana de Ginecología y Obstetricia

On-line version ISSN 2304-5132

Rev. peru. ginecol. obstet. vol.67 no.3 Lima July/Sept. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.31403/rpgo.v67i2335

Review Articles

Sexual and reproductive rights in Peru, beyond the Bicentenary

1 President of the Committee on Sexual and Reproductive Rights, Peruvian Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology (SPOG). Former President SPOG. Scientific Editor, The Peruvian Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. Honorary Member of 6 Latin American Obstetrics and Gynecology Societies. Latin American Master of Gynecology and Obstetrics. Former Executive Director of FLASOG. Fellow American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists

Objective

: To clarify the concept of sexual and reproductive health, to situate it within Human Rights and, as a consequence, within Sexual and Reproductive Rights; to discuss some gender issues; to examine the situation of sexual and reproductive rights in our country and what we expect for the years to come.

Methodology

: Review of the national medical literature in relation to sexual and reproductive rights and systematize the information.

Results

: In the various components of sexual and reproductive health there are important deficiencies that need to be overcome in order to achieve the well-being indicated by the Sustainable Development Goals.

Conclusion

: There is still much to be developed in the recognition of sexual and reproductive rights, appealing to the best performance and commitment of health professionals.

Key words: Human rights; Reproductive rights; Sexual and reproductive Health.

INTRODUCTION

Nowadays, health care must be carried out with a human rights (HR) approach based on respect for the dignity of individuals, given that the human being is the center of action of the State. This implies equal treatment and non-discrimination in health care1,2. Human rights are a power or prerogative to demand a certain conduct from a third party. They are the expression of certain values: dignity, freedom, equality. It refers to the rights of citizens vis-à-vis the State and the international community. The State has the obligation to: guarantee the enjoyment of and access to rights, not hinder people from enjoying a right, eliminate barriers that prevent the enjoyment of and access to rights. This implies adapting laws and/or their interpretation. Human rights are interdependent, progressive and should be interpreted as favorably as possible to individuals3.

The international normative framework recognizes sexual and reproductive rights (SRR) as human rights, that is, as an indivisible, integral and inalienable part of universal human rights. However, reality shows that, in the development of these rights, low levels of recognition, deepening and exercise still persist, especially among the most vulnerable sectors of the population. In practically each and every one of the rights there are deficiencies and obstacles that are very difficult to overcome, even in the most elementary aspects4.

SRHR are universal human rights, based on freedom, dignity and equality, inherent to all human beings4-8. They are recognized as Sexual Rights(SR):

The right to have sexual relations free from any form of violence, abuse or harassment.

The exercise of a free and pleasurable sexuality, independent of reproduction and without risk to health and life.

Access to sexuality education that is timely, comprehensive, gradual, scientific and with a gender perspective.

Respect for people's sexual preference.

To have access to information and services for the prevention and treatment of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including HIVAIDS.

The following are recognized as Reproductive Rights /RR):

To make free and responsible reproductive decisions, which includes the right to decide whether or not to have children, the number of children, and the time to elapse between each one.

To have full access to methods to regulate fertility by one's own choice.

To have access to quality SRH care services during all life cycles.

Receive emergency care and have all the necessary supplies to guarantee safe motherhood before, during and after childbirth.

Not to be discriminated against at work, school and in society for being pregnant or for having or not having children.

Thus, SRHR are integral elements of the rights of all people to enjoy the highest attainable standard of physical, mental and social health9.

SEXUAL HEALTH (SH) AND REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH (RH)

Sexual health is the possibility of enjoying mutually satisfying sexuality, free from abuse, harassment or sexual coercion, of being safe from sexually transmitted diseases and the possibility of achieving or preventing an unwanted or unplanned pregnancy10.

The concept of reproductive health is one of the milestones in the social history of the 20th century. It was developed as a result of experience during the 1970s and 1980s and became universally valid with the consensus of the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development in Cairo. The difference between women in rich and poor countries lies in the level of RH7,8.

The understanding of RH has advanced significantly in recent decades. The field of RH is different from other health fields. The involvement of society at large and the consequences for that society are different in other areas of medicine and health and for no less reason than human reproduction; it is the means by which each society perpetuates itself and its traditions. No society, religion, culture, or national system of law has been neutral on the issue of human reproduction. Progress in RH, much more than any other field of health, requires input and good performance from health care providers, health policy makers, legislators, lawyers, human rights activists, women's groups, and society in general10.

ETHICAL ASPECTS

SRH care often raises medical, ethical and bioethical issues in particularly complex ways. Dilemmas may arise between the ethical principles of the relationship between a health care provider and a patient and the ethical principles that apply to health care providers as members of a community. When a professional decides whether or not to provide the requested services, he or she may be forced to confront and define his or her personal ethics and personal and professional contribution to both the health of the patient and the character and conscience of his or her community. Professionals are confronted with issues as old as abortion care or as modern as the appropriate use of advanced reproductive technologies, including the creation of human embryos outside the woman's body to overcome the effects of infertility. Bioethics studies the basic issues of human, institutional, and societal management of birth, disease, and death of human beings, but it has attracted public attention through technological developments10. The provider may also invoke his or her right to conscientious objection to the performance of certain procedures, but in this case would be obliged to refer the patient to a colleague who is known to be able to solve the problem11.

GENDER CONSIDERATIONS

Despite advances in SRH and health sector reforms, due consideration has not yet been given to the fact that men and women present differences in their health, since women have greater needs for services, due to their biology and reproductive function. On the other hand, there is still discrimination, inequity and exclusion of a significant number of women, especially the poorest ones, which puts their health at serious risk2. If SRH is to be achieved, people must be given information so that they can exercise control over their lives and access to related health services must be guaranteed. While these rights and the ability to exercise them are an important value in themselves, they are also a condition for well-being and development. The neglect and disorganization of SRH services and associated rights are the cause of many health-related problems around the world. Incidentally, the burden of disease in RH is 20% in women and 14% in men10,12.

Many of the health problems related to sex or sexuality depend on the nature of power relations between men and women. A key indicator of the differences between men and women is maternal death (MM). As we know, there is no "paternal death" related to pregnancy or childbirth, because this only occurs in women. One of the main causes of MM is abortion, which men do not suffer either2. To the above we must also add that women suffer more gender-based violence13, a greater burden of STIs, that HIV infection is increasingly frequent at the point of departure of heterosexual relations; and as if that were not enough, women suffer more social and economic inequalities, having less education, less economic capacity and less decision-making capacity.

COMMITMENT OF THE MEDICAL-SCIENTIFIC SOCIETIES

In 2002, during the Latin American Congress of Obstetrics and Gynecology held in the city of Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Bolivia, the Latin American Federation of Obstetrics and Gynecology Societies (FLASOG, by initials in Spanish) officially created the Committee on Sexual and Reproductive Rights and in that same Congress, the FLASOG Assembly approved the Declaration of Santa Cruz, in which it assumed the defense of the following sexual and reproductive rights:

Right to a healthy and safe motherhood, without risk of death.

The right to a sexual life free of violence and the risk of contracting a sexually transmitted infection and unwanted pregnancy.

Right to regulation of fertility through access to contraceptive methods including emergency contraception

The right to termination of pregnancy within the framework of the law.

The right to information on sexual and reproductive health.

The right to access sexual and reproductive health services.

To these rights, as part of this work, we must add the health of adolescent girls.

Taking as a framework the list of rights whose defense has been assumed by FLASOG and, therefore, by the Peruvian Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology, this article aims to clarify the concept of sexual and reproductive health, to situate SRH within Human Rights and, as a consequence, within Sexual and Reproductive Rights, discuss some gender issues, examine the situation of SRHR in our country14, which we hope for the coming years after making some approaches for its improvement and meeting the Sustainable Development Goals15.

METHODOLOGY

According to the editor of The Peruvian Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics (RPGO), research has contributed to our reality in reproductive medicine, early diagnosis of gynecological cancer, proper care of childbirth, reduction of maternal and perinatal mortality, obstetric hemorrhage, preeclampsia, gestation and newborn at high altitude, contraception, menopause, genital prolapse and urinary incontinence, breast pathology, genetics, ultrasound, endoscopic surgery, and many other related topics16, but we add that much more than that is missing.

The author has carried out a systematization of the Peruvian medical literature, taking as a source the publications published in the RPGO from the year 2000 to May 2021, where sexual and reproductive health and rights issues are reported and have been made known as part of the knowledge or interventions in the different work environments. Likewise, during this period, we have reviewed publications in national books or other types of publications, such as Peruvian Health Ministry reports and the Demographic and Family Health Survey (ENDES) 2020, where these issues are reported.

They were then grouped according to subject matter in the form of tables in order to present the results and discuss them in the respective section.

It has not been necessary to submit the results to statistical analysis or to request informed consent from individuals, since only the review of existing information has been dealt with.

RESULTS

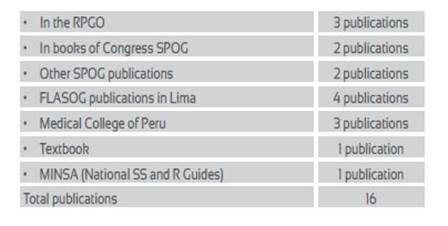

On sexual and reproductive rights and SRH in general, the following publications have been produced:

Among these 16 publications, the National Guidelines for Comprehensive Sexual and Reproductive Health Care published by MINSA in 2004 with the aim of unifying criteria for women's health care based on respect for their rights stands out17.

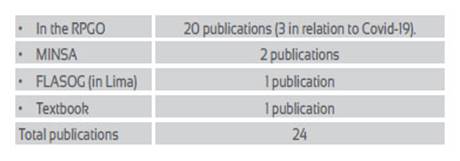

The following publications have been produced on the right to a healthy and safe maternity, without risk of death:

Outstanding among these 24 publications is a MINSA report and 3 papers in the RPGO that address the issue of MM produced by Covid-19.

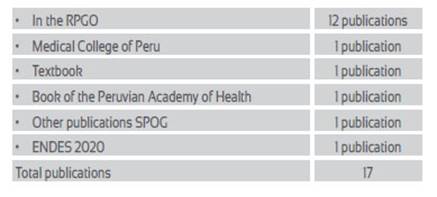

On the right to Family Planning (contraception) the following publications have been produced:

Among these 17 publications, ENDES 2020 stands out, which gives an account of the current state of family planning, maternal and child health, adolescent reproductive health and the situation of domestic violence18.

The following publications have been produced on the right to enjoy a sexual life free of violence:

Among these 11 publications, one by FLASOG stands out, which attempts to develop the care of sexual violence centered in a health institution and the close coordination with legal aspects, with the purpose of ensuring the provision of health care without subjecting the victims to revictimization.19).

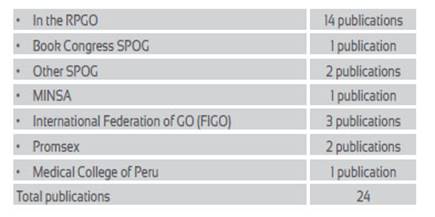

The following publications have been produced on the right to termination of pregnancy according to the country's legislation:

Among these 24 publications, those promoted by FIGO as part of a worldwide intervention, "FIGO Initiative for the Prevention of Unsafe Abortion", in which Peru played an important role, stand out. Also noteworthy is the publication by MINSA of the National Guide for Comprehensive Care of Termination of Pregnancy up to 22 weeks, because it technically regulates the care of therapeutic abortion20.

In relation to the right to sexual and reproductive health of adolescents, the following publications have been produced:

Of the total of 12 publications, the MINSA document Multisectoral Plan for the Prevention of Adolescent Pregnancy21 stands out.

DISCUSSION

From the results of this search, it can be seen that there is little interest in publishing works or interventions in relation to sexual and reproductive health and rights, which represents a debt to the women of Peru.

According to the current President of SPOG, it is considered that the COVID-19 pandemic has revealed an outdated health system in the country due to the little importance given to it by the Peruvian government. There is lack of adequate implementation of health institutions, scarce preparation for health catastrophes, failure in primary health care, closure of the first level of care during the pandemic, scarcity of human resources prepared to attend emergencies, intensive care units. The failure to consider pregnancy as a risk factor for COVID-19 infection, among others, has caused the pandemic to have a profound impact on the health of the population in general and on women in particular. Likewise, there is a clear lack of health research and limited studies in the field of Peruvian women's health at different ages of life22. This also implies the need to train human resources in sexual and reproductive health from university classrooms23. Let us now look at each of the rights that FLASOG is committed to defend.

On the Right to a healthy and safe motherhood, without risk of death (maternal mortality)

Maternal mortality is defined as the death of women during pregnancy or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy, regardless of the duration and place of pregnancy, from causes related to or aggravated by gestation or its management, but does not include incidental or accidental causes24. It is the most sensitive indicator of the level of reproductive health care, because it usually expresses the large gaps existing within populations, where it is the most unprotected, excluded and discriminated women who end their pregnancies with a tragic death25.

At the international level, there is great concern about the high rates of preventable maternal mortality and morbidity, which is not foreign to Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC). MM continues to be a serious human rights problem that dramatically affects women and has repercussions on their families and communities. For this reason, efforts have been made to assess the weight of different technologies in the reduction of maternal mortality, and the safety offered by the provision of services by skilled personnel at the time of delivery has become clear26.

Peru has been developing many activities and interventions to reduce MM figures, following the WHO commitment in Nairobi in 1987. In the year 2000, the United Nations (UN) Millennium Development Goals were set, one of which established the goal of reducing the MM ratio by 75% by 201527, which Peru came very close to achieving, having remained slightly above the 66% set for that time.

Safe motherhood means achieving optimal health for the mother and the newborn. It involves reducing maternal mortality and morbidity and improving newborn health through equitable access to primary health care, including family planning, care during pregnancy, childbirth and after birth for both mother and child, and access to basic obstetric and neonatal services28. For this reason, so far this century, MINSA, cooperation institutions and civil society have made important interventions. For example, the implementation of the Ten Steps to Safe Childbirth strategy was completed, which led to a significant decrease in MM in 4 regions of the country29. MINSA completed its Project 2000 with the cooperation of the U.S. Agency for Institutional Development (AID), which also led to a reduction in the MM ratio (MMR) in the intervened regions. SPOG in partnership with FIGO implemented the MM reduction program in the sub-region of Morropón-Chulucanas in the Piura region, with encouraging results.

The Ministry of Health strengthened its MM Reduction Program with the clear intention of meeting the millennium goals and has continued to implement it, so that the figures have been declining to reach an MMR of 55.1 per 100 000 live births by 2019. However, during the year 2020, as a consequence of the Covid-19 pandemic, the MMR has risen to 81.6 per 100 000 live births30.

Through the Sexual and Reproductive Health Strategy of MINSA, it is known that in 2020 the MM has risen by 42%; its causes were: pregnancy-induced hypertension (PIH) 20.5%, hemorrhage 17.2%, Covid-19 14.7%. There is a marked increase in violence against women. Maternal death has increased in the beginning of 2021 -corresponding to what is happening with deaths in the Peruvian population and in the world-, especially indirect maternal death caused by Covid-19 infection, which rose from 16.6% in 2020 to 36% up to the 13th week of 2021. It is important to know that, of the direct causes of MM, hypertensive disorders increased slightly between 2019 and 2020 (from 19.5% to 21.4%, and were the first cause of direct MM), and in the first trimester of 2021 their incidence dropped to 15.8%, being surpassed by obstetric hemorrhage (19.3%), which, however, seems to be declining since 2019 (25.9%). We cannot fail to mention the association found in various publications on a possible association between SARS-CoV-2 virus infection and preeclampsia31,32.

To achieve number 3 of the Sustainable Development Goals, several interventions will be necessary after the bicentennial:

Emphasize the social and economic determinants of MM.

Consider in public policies greater health coverage, universal access to services, allocation of resources, use of evidence-based interventions and South-South cooperation.

Strengthen the primary health care strategy.

Consider in health systems respect for the SRR, equity, quality of care, resolution capacity, timely detection and management of emergencies: hypertension, hemorrhage, complicated abortions, training of personnel and clarification and strengthening of the role of professional midwives.

Availability of information and surveillance: update data, use information on extreme maternal morbidity.

Use contraception, improve counseling, use effective contraceptive methods (MAC), promote the use of long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARC), respect the right to decide, make SRH supplies available.

Provide adequate response to cases of unsafe abortion in accordance with the law and the country's norms.

Mobilize maternal death committees.

Improve registries.

Use the International Classification of Diseases, ICD11 from the year 2022.

Empower women through better information, access to education, equal opportunities and recognition of their right to make their own decisions.

Improve the performance and commitment of health professionals.

Regarding MM and Covid-19: reduce the impact, maintain continuity of services, prioritize vaccination, consider SRH services essential with a better allocation of personnel.

RIGHT TO FAMILY PLANNING (FP)

Sigmund Freud, even before the definition of SRH and SRR, said "One of the greatest triumphs of humanity would be to elevate the responsibility for the act of reproduction to the level of voluntary and intentional action", as if to say that the reproductive function should be subordinated to the decision and will of individuals and not to a fortuitous fact, imposed by third parties or by society. It is precisely family planning -and contraceptionthat plays an important role in this issue. The Population Reference Bureau maintains that every pregnancy should be desired and that, thanks to the revolution in technology, fertility today should be achieved by choice, which has led to a significant decrease in the fertility rate and therefore to a decrease in the risk posed by pregnancy and childbirth33.

FP is an effective primary prevention measure to reduce unwanted pregnancy. From the available data it can be stated that 1/4 to 2/5 of MM can be eliminated if these pregnancies are avoided through contraception18.

In Peru, there has also been progress in FP until the beginning of the first decade of the present century, when the corresponding program not only weakened, but disappeared as such, and FP activities suffered some setbacks, such as logistical difficulties, shortage of supplies, extreme reduction in the supply of surgical contraception, and reduction of training and supervision activities34.

According to the DHS 2000, the total fertility rate has been progressively decreasing and today stands at 1.9 children per woman at the end of her reproductive years, and the interval between births is an average of 62.2 months. The prevalence of contraceptive use is apparently high (77.4%), 55% of which corresponds to modern methods, among which injectable contraceptives are the most widely used (17.1%). Long-acting contraceptive methods (LARC) hardly appear in the public sector, although their frequency of use is higher in the private sector, very similar to that of emergency contraception. Traditional methods are used with a frequency of 22.3%, with the periodic abstinence method being the most widely used, with the exception that only 50% of the women who use it know their ovulatory days. Of all women of childbearing age, 52% no longer wish to have children, 6.1% have an unmet demand for contraceptives, 52.1% have had unwanted pregnancies and the total demand for contraceptives is 87.1%18).

To fulfill this right, there are still pending issues in FP in Peru after the bicentennial34:

Expand FP services, starting at the first level of care.

Ensure good logistics that diversify contraceptive methods.

Improve SRH information for women.

Improve the quality of care and user choice.

Reduce unmet need for contraception.

Facilitate voluntary surgical contraception in public services.

Availability of a wider range of contraceptive methods, including emergency contraception and long-acting reversible methods35.

RIGHT TO ENJOY A SEXUAL LIFE FREE OF VIOLENCE

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines violence against women as any act of gender-based violence that results in physical, sexual or psychological harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or private life. Six out of 10 women suffer physical or sexual violence in their lifetime, 7 to 36% of women suffer sexual violence in childhood, and 6 to 59% of women suffer sexual violence after the age of 15. Intimate partner violence is the most common form of violence against women worldwide36.

According to the ENDES 2020, 54.8% of women were victims of violence perpetrated at some time by a husband or partner, with a tendency to be higher in urban area residents (55.3%) compared to rural area residents (52.3%). Among the forms of violence, psychological and/or verbal violence stands out (50.1%), which is aggression through words, insults, slander, shouting, insults, scorn, mockery, irony, situations of control, humiliation, threats and other actions to undermine self-esteem, followed by physical violence (27.1%), which is aggression exercised through hitting, pushing, kicking, slapping, among others. And finally, sexual violence (6.0%), which is the act of coercing a woman to perform sexual acts that she does not approve of, or forcing her to have sexual relations18. However, these figures correspond to women of childbearing age who are in union and leave out those under 15 years of age and those over 49 years of age.

Age is not a barrier that prevents violence, since girls, adolescents and adult women can suffer physical and psychological injuries and, in extreme cases, death. However, it is women of reproductive age who may face the greatest consequences. If a woman is a victim of violence, she may suffer lifelong repercussions, and those who are abused as children are at even greater risk of becoming victims as adults19.

Social tolerance of violence makes it difficult for women to report physical and sexual abuse and therefore statistical information becomes questionable. On the other hand, health professionals, due to their eminently biomedical orientation, do not inquire about the women they treat, do not give it due importance, because they consider it a private matter, and women who have been sexually abused avoid making a complaint because they do not trust health providers or those who impart justice19.

One of the most common forms of violence against women is abuse by their husbands or intimate partners, who use it as a form of control over them and an expression of power imbalance. Sexual coercion exists as a continuum, from forced rape to other forms of pressure that push girls and women to have sex against their will. For many women, sexual initiation was a traumatic event accompanied by force and fear19.

Studies carried out in the community and within reproductive health services in Peru reveal that the rates of sexual violence against women are relatively high when compared to other regions of the world37,38. Violence against women in any form occurs at any time in their lives and pregnancy is not a protective factor. Violence during pregnancy is more frequent than any of the gestational pathologies. What happens is that it is not detected or, if it is, it is not given due importance. Reproductive health services in Peru find that violence in any of its forms occurs in 31.9% of pregnant women; psychological violence in 23.3%, physical violence in 7.4% and sexual violence in 7.1%, although with some frequency two or three types of violence can coexist on the same woman39.

The repercussions of violence against women are well identified. It can have fatal consequences, such as homicide, suicide, maternal death or death due to HIV/AIDS. It can also have non-fatal consequences on general physical health, mental health, chronic injuries and disabilities, and sexual and reproductive health problems. Sexual violence can result in shortand longterm health consequences for women, including physical trauma, such as vaginal fistula, HIV infection, unwanted pregnancy, and unsafe abortion. Vulnerability to STIs, including HIV may be higher than in consensual sex, due to genital trauma and in the case of multiple perpetrators. The resulting psychological trauma may have a negative effect on sexual behavior and relationships, the ability to negotiate safer sex, and a potential increase in substance abuse40-43.

In relation to sexual violence, it is important to recognize that timely and quality care has a positive and significant impact on addressing the consequences and preventing complications of rape, which affect quality of life by perpetuating emotional, biological and social damage, including forced pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections43. Notwithstanding this statement, in much of Latin America and specifically in Peru, there are still no comprehensive care services for victims of sexual violence that ensure early attention.

In addition to the early approach to these cases, the following should be expected after the bicentennial14:

Effective legislation to comprehensively manage sexual violence (SV) requires functioning medico-legal linkages to enable the enforcement of justice and the provision of health services for survivors.

The health sector must provide post-rape care services and collect and deliver evidence to the justice system.

Services should be integrated through referrals, using guidelines and consultation pathways, treatment protocols and standardized medico-legal procedures.

The health sector is the nexus between prevention, treatment and rehabilitation following SV. This sector should provide clinical treatment, preventive therapy, psychological support, information and counseling, and coordinate referral of victims to specialized services.

Empower women.

Expand and improve SRH services.

Detect cases of violence against women in the daily care routine.

Provide early and comprehensive care for sexual violence.

Coordinate with other health and legal services so as not to re-victimize women.

RIGHT TO TERMINATION OF PREGNANCY WITHIN THE FRAMEWORK OF THE LAW

Despite high contraceptive prevalence and the existence of safe and effective methods of abortion, millions of unsafe abortions continue to occur worldwide each year. This is not only because all contraceptive methods occasionally fail and because people do not use them consistently, resulting in unwanted pregnancies, but also because millions of women around the world do not have access to safe abortion services when they choose to terminate a pregnancy within the framework allowed by law. Where abortion is legally restricted, some women will have unwanted children; however, most women end up having unsafe abortions. Whatever the method of termination used, abortion can be incomplete or lead to serious complications; hence the need for good postabortion care in a timely manner, because its delay threatens women's lives and health(14). According to Lancet, between 2015-19 there were 121 million unintended pregnancies (UIP) worldwide annually, which corresponds to 64 UIP per 1 000 women aged 15-49 years. Sixty-one percent of those UIPs ended

in abortion (totaling 73.3 million abortions annually and corresponding to a global abortion rate of 39 per 1 000 MEF. In countries where abortion was restricted, a higher proportion of UIPs ended in abortion44.

We do not know the exact figures for abortion in Peru, since it is a clandestine practice. However, Ferrando's studies, using indirect methodology, which has proven to be effective, have been able to determine that more than 370,000 induced abortions occur in the country each year. This means the occurrence of more than 1 000 abortions per day, a rate of more than 50 per 1 000 women in fertile age, higher than the average for Latin America. The vast majority of these abortions are unsafe, causing complications and eventually maternal deaths(45). Precisely, to avoid deaths and severe complications, it is necessary to provide early, efficient and humanized care for women who come to a health facility with complications arising from an abortion and not subject them to unnecessary delays for proper care, since this can lead to death46.

On the other hand, most abortion complications that come to the hospital are mild or moderate bleeding and are managed with uterine curettage or manual vacuum aspiration. Nowadays they can also be successfully treated by oral or sublingual administration of misoprostol, without the need for surgical management47.

In recent years there have been extremely important interventions in Peru for the prevention and management of abortion. Chronologically, we will first cite the FIGO Initiative for the prevention of unsafe abortion carried out in 43 countries in the world, one of which was Peru, with the co-participation of SPOG and MINSA, with flattering results48. Then we will cite the approval by MINSA of the National Guidelines for Termination of Pregnancy up to 22 weeks20 and, finally, the SPOG-FIGO project being developed in Peru for therapeutic abortion advocacy.

In addition to the above-mentioned interventions, we should expect to see several activities after the bicentennial to prevent the occurrence of unsafe abortion and its serious consequences:

Do sex education early in the life of girls.

Improve FP services and supply.

Implement the National Therapeutic Abortion Guidelines with a strong commitment from health professionals.

Reformulate the legislation on therapeutic abortion and include serious congenital malformations and pregnancies resulting from rape as grounds for abortion.

Promote the clarification of values among health professionals.

Humanized care for incomplete abortion, respecting the privacy of the user.

Develop post-abortion contraception, promoting LARCs.

ADOLESCENTS' RIGHT TO SEXUAL AND REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH

Adolescent girls' sexuality is characterized by difficulty in agreeing on a behavioral model with their partners, as well as by unstable relationships, emotional conflicts, secrets, rebellious attitudes and, frequently, unprotected sexual relations, especially in the early stages of their sexual activity. Adolescent girls are also frequently exposed to gender based violence (GBV) and especially to sexual violence. As a result of these conditions, many unwanted pregnancies occur during adolescence, when girls and their partners become sexually active without considering the need for contraception or having access to appropriate services49.

Adolescent reproductive behavior is an issue of recognized importance, not only in terms of unwanted pregnancies and abortions, but also in relation to the social, economic and health consequences. Pregnancies at a very early age are part of the cultural pattern of some regions and social groups. They usually occur in couples who have not started a life together, or take place in situations of consensual union, which brings physical, emotional and social consequences, including the loss of continuity in their studies and employment difficulties. It usually forces couples to take refuge in the family home and unfortunately ends with the abandonment of the woman and child, thus configuring the social problem of the single mother. On the other hand, many of these pregnancies end in abortions performed by people without proper professional training and in inadequate sanitary conditions, since specialized medical services are scarce and expensive. In addition, abortion is illegal in Peru50. Of the total number of adolescents aged 15 to 19 years, 8.2% had ever been pregnant; of these, 6.5% were already mothers and 1.7% were pregnant for the first time. Of all adolescents aged 12 to 17 years, 2.3% had ever been pregnant; of these, 1.7% were already mothers and 0.6% were pregnant for the first time. Contraceptive use is still low from the beginning of their sexual life18.

Given the adverse repercussions of adolescent pregnancy, in 2013 MINSA approved the Multisectoral Plan for its reduction21, in addition to other interventions by MINSA, international organizations and civil society institutions. However, there are still activities to be carried out after the bicentennial:

Provide early information and education to adolescent girls at school.

Promote gender equity.

Promote self-esteem among adolescent girls.

Provide adolescent-friendly sexual and reproductive health services.

Provide counseling on safe motherhood, sexually transmitted diseases and violence.

Respect privacy and confidentiality.

Protect adolescents from potential sexual assault.

Facilitate provision of modern contraceptives, including emergency contraception.

Provide humane abortion management.

Offer voluntary termination of pregnancy services in cases established by law.

FINAL COMMENT

Women's SRR are integral to the daily practice of the obstetrician-gynecologist and are key to the survival and health of women around the world. The OG physician is a natural advocate for women's health, but may still be lacking greater commitment and the need to make the practice of medicine person-centered, as well as meeting goals 3 and 5 of the Sustainable Development Goals15,51,52.

There is a growing awareness of the reciprocal relationship between SRH problems and specific indicators of general well-being, such as poverty. SRH problems are both a cause and a consequence of poverty. Poor SRH impacts the economic well-being of individuals, families and communities by reducing productivity and labor force participation. For example, early childbearing increases poverty among girls by thwarting their life plans and limiting their employment opportunities, thereby maintaining the poverty cycle; at the same time, the costs of treating SRH damage can deplete meager incomes, exacerbating individual and household poverty53. Using a rights-based approach to SRH offers a powerful lens for examining those normative regimes and how they hinder women from achieving their reproductive health rights54.

REFERENCES

1. Constitución Política de la República del Perú, 1993. [ Links ]

2. Fathalla MF. From Obstetrics and Gynecology to women's health: the road ahead. New York and London: Parthenon, 1997. [ Links ]

3. Siverino P. Apuntes sobre derechos sexuales y reproductivos en el ordenamiento jurídico argentino. En: Arribere R. Bioética y Derecho: Dilemas y Paradigmas en el siglo XXI. Buenos Aires, Argentina: Cátedra Jurídica 2008: 87-207. [ Links ]

4. Instituto Interamericano de Derechos Humanos. Los Derechos Reproductivos son Derechos Humanos. San José, Costa Rica: IIDH 2008; 86 pp. [ Links ]

5. Quiroga CA, Ochoa JA, Andrade XV. El derecho al aborto y la objeción de conciencia. En: IPAS, Reproducción. La Paz: Ipas 2009: 77 pp. [ Links ]

6. V Congreso Latinoamericano y I Congreso Centroamericano de Salud y Derechos Sexuales y Reproductivos. Conclusiones. Ciudad de Guatemala 5-7 Mayo 2010. [ Links ]

7. UNFPA. Conferencia Internacional de Población y Desarrollo. El Cairo 1994. [ Links ]

8. Naciones Unidas. Declaración y Plataforma de Acción: Cuarta Conferencia Mundial sobre la Mujer. Beijing: ONU, 1995. [ Links ]

9. World Association for Sexual Health. Salud sexual para el milenio. Declaración y documento técnico. Washington DC: OPS/OMS 2009; 180 pp. [ Links ]

10. Cook RJ, Dickens BM, Fathalla MF. Salud Reproductiva y Derechos Humanos, 2a Ed, traducida al español. Bogotá-Colombia: Profamilia 2005; 605 pp. [ Links ]

11. FLASOG. Comité de Derechos Sexuales y Reproductivos. Taller sobre objeción de conciencia, Relato Final. II Congreso Internacional Jurídico sobre Derechos Reproductivos, San José, Costa Rica 28-30 Noviembre 2011: 26 pp. [ Links ]

12. WHO. What constitutes sexual health? Progress in Reproductive Health Research N° 67, 2004. [ Links ]

13. García-Moreno C, Jansen HA, Ellsberg M. et al. WHO multi country study on women's health and domestic violence against women: initial results on prevalence, health outcomes and women's responses. Geneva: WHO 2005. [ Links ]

14. Távara L. Derechos Sexuales y Reproductivos. En: Noriega L, Llerena C, Prazack L. Tratado de Reproducción Humana Asistida. Lima, Perú: REP SAC. 2013: 14-27. [ Links ]

15. ONU. Objetivos de desarrollo sostenible. New York: ONU, 2015. [ Links ]

16. Pacheco-Romero J. Contribución de la Sociedad Peruana de Obstetricia y Ginecología a la especialidad del país a sus 70 años de creación, valuada a través de las páginas de la Revista Peruana de Ginecología y Obstetricia. Rev Peru Ginecol Obstet. 2017;63(3):333-45. [ Links ]

17. Ministerio de Salud. Guías Nacionales de Atención Integral de la Salud Sexual y Reproductiva. Lima, Perú: Dirección General de Atención de la Salud de las Personas, Junio 2004. [ Links ]

18. Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Encuesta Nacional de Demografía y Salud 2020. Lima-Perú: INEI 2021. [ Links ]

19. Ortiz JD, Rosas C, Távara L. Propuestas de estándares regionales para la elaboración de protocolos de atención integral temprana a víctimas de violencia sexual. Lima-Perú: Comité de Derechos Sexuales y Reproductivos de FLASOG 2011; 88 pp. [ Links ]

20. Ministerio de Salud. Guía Nacional para la Atención Integral de la Interrupción del embarazo hasta las 22 semanas. Lima-Perú: Minsa 2014. [ Links ]

21. Ministerio de Salud. Plan Multisectorial para la Prevención del embarazo en adolescentes. Lima, Perú: Minsa 2013. [ Links ]

22. Ciudad Reynaud A, Pacheco-Romero J. Situación de la mujer y la gestante en el Perú. Perspectivas desde la Sociedad Peruana de Obstetricia y Ginecología. Rev Peru Ginecol Obstet. 2021;67(1). DOI: https://doi.org/10.31403/rpgo.v67i2298. [ Links ]

23. Távara L (editor). III Taller Latinoamericano de FLASOG sobre mortalidad materna y de derechos sexuales y reproductivos. Rev Per Ginecol Obstet. 2006;52(3):159-62. [ Links ]

24. UNICEF. Maternal mortality. https://data.unicef.org/topic/maternal-health/maternal-mortality/. ConsultedJune 2021. [ Links ]

25. WHO. Reproductive health indicators for global monitoring. Geneva: WHO 2001. [ Links ]

26. Organización de los Estados Americanos. CIDH. Acceso a servicios de salud materna desde una perspectiva de Derechos Humanos. Washington DC: Secretaría General de la OEA, 2010; 36 pp. [ Links ]

27. UNFPA. The Global Programme to Enhance Reproductive Health Commodity Security. Annual Report. New York: UNFPA 2010: 104 pp. [ Links ]

28. Távara L. Cómo lograr una maternidad segura en el Perú. Ginecol Obstet Peru. 2001;47(1):12-5. [ Links ]

29. Távara L, Sacsa D, Frisancho O, Urquizo R, Carrasco N, Tavera M. Mejoramiento de la calidad en la prestación de los servicios como estrategia para reducir la mortalidad materna y perinatal. Ginecol Obstet Peru. 2000;46(2):124-34. [ Links ]

30. Ministerio de Salud, Centro Nacional de Epidemiología, Prevención y Control de Enfermedades. Situación epidemiológica de la mortalidad materna en el Perú. 2021. [ Links ]

31. Vigil-De Gracia P, Carlos Caballero L, Ng Chinkee J, Luo C, Sánchez J, Quintero A, Espinosa J, Campana Soto SE. COVID-19 y embarazo. Revisión y actualización. Rev Peru Ginecol Obstet. 2020;66(2): DOI: https://doi.org/10.31403/rpgo.v66i2248 [ Links ]

32. Collantes Cubas JA, Pérez Ventura SA, Vigil De Gracia P, Castañeda Bazán KE, Tapia Saldaña JM, Leyva FJ. Maternal mortality in pregnant women with positive SARSCoV-2 antibodies and severe preeclampsia. Report of 3 cases. Rev Peru Ginecol Obstet. 2020;66(4). DOI: https://doi.org/10.31403/rpgo.v66i2279 [ Links ]

33. Population Reference Bureau. World population data sheet: Demographic data and estimates for the countries and regions of the world. Washington DC: PRB 2000. [ Links ]

34. Távara L. Análisis de la oferta de anticonceptivos en el Perú. Rev Peru Ginecol Obstet. 2010;56(2):87-103. [ Links ]

35. Gutiérrez Ramos M. Controversias sobre anticoncepción. Los métodos reversibles de larga duración (LARC), una real opción anticonceptiva en el Perú. Rev Per Ginecol Obstet. 2017;63(1):83-8. [ Links ]

36. WHO. Violence against women. Geneva: WHO, June 2000. [ Links ]

37. Guezmes A, Palomino N, Ramos M. Violencia sexual y física contra la mujer en el Perú. Lima-Perú: CMP Flora Tristán-OPS/OMS-Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia 2002: 119 pp. [ Links ]

38. Távara L, Zegarra T, Zelaya C, Arias ML, Ostolaza N. Detección de violencia basada en género en tres servicios de atención de salud reproductiva. Rev Peru Obstet Gineco. 2003;49(1):31-8. [ Links ]

39. Távara L, Orderique L, Zegarra T, Huamaní S, Félix F, Espinoza K, Chumbe O. Repercusiones maternas y perinatales de la violencia basada en género. Rev Peru Ginecol Obstet. 2007;53(1):10-7. [ Links ]

40. Devries KM, Kishor S, Johnson H, Stockl H, Bacahus LJ, García-Moreno C, Watts C. Intimate partner violence during pregnancy: analysis of prevalence data from 19 countries. Reproductive Health Matters. 2010;18(36):158-70. [ Links ]

41. Stockl H, Watts C, Mbwambo JK. Physical violence by a partner during pregnancy in Tanzania: prevalence and risk factors. Reproductive Health Matters. 2010;18(36):171-80. [ Links ]

42. WHO. Guidelines for medico-legal care of victims of sexual violence. Geneva: WHO 2003. [ Links ]

43. Távara L. Sexual violence. Clin Obstet Gynaecol. Best practice & research. 2006;20(3):395-408. [ Links ]

44. Bearak J, Popinchalk A, Ganatra B, Moller AB, Tunçalp Ö, Beavin C, Kwok L, Alkema L. Unintended pregnancy and abortion by income, region, and the legal status of abortion: estimates from a comprehensive model for 1990-2019. Lancet. July 22, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214109X(20)30315-6 [ Links ]

45. Ferrando D. El aborto clandestino en el Perú. Lima: Centro de la Mujer Peruana Flora Tristán/Pathfinder International 2006. [ Links ]

46. Maradiegue E. Aborto como causa de muerte materna. Rev Per Ginecol Obstet. 2006;52(3):89-99. [ Links ]

47. Singh S. Hospital admissions resulting from unsafe abortion: estimates from 13 developing countries. Lancet. 2006; 368(9550): 1887-92. [ Links ]

48. Faundes A, Comendant R, Dilbaz B, Jaldesa G, Leke R, Mukherjee B, Padilla de Gil M, Tavara L. Preventing unsafe abortion: Achievements and challenges of a global FIGO initiative. The FIGO Initiative for the Prevention of Unsafe Abortion. Best Practice & Research Clin Obstet Gynaecol. January 2020;62:101-12. [ Links ]

49. Távara L. Contribución de las adolescentes a la muerte materna en el Perú. Ginecol Obstet Peru. 2004;50(2):111-22. [ Links ]

50. Távara L, Orderique L, Sacsa D y col. Impacto del embarazo sobre la salud de las adolescentes. Lima: Promsex 2015: 76 pp. [ Links ]

51. Salazar Marzal E. El problema de la seguridad de la atención. Rev Peru Ginecol Obstet. 2019;65(1):31-5 DOI: https://doi.org/10.31403/rpgo.v65i2149 [ Links ]

52. Vera Loyola E. Atención del parto centrada en el paciente. Rev Peru Ginecol Obstet. 2019;65(1):51-5. [ Links ]

53. Family Care International. Millenium Development Goals & Sexual and Reproductive Health. New York: FCI 2005. [ Links ]

54. WHO, UNFPA. Mental Health aspects of women's reproductive health. Geneva: WHO 2009; 181 pp. [ Links ]

Received: June 22, 2021; Accepted: June 23, 2021

text in

text in