Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Revista Peruana de Ginecología y Obstetricia

On-line version ISSN 2304-5132

Rev. peru. ginecol. obstet. vol.67 no.4 Lima Oct./Dec. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.31403/rpgo.v67i2370

Special Articles

Fetal brain assessment: new tools

41. Obstetrician-Gynecologist, Hospital Nacional Daniel Alcides Carrión-Callao

2. Fetal Medicine Center: CENMEF. Clínica Santa Isabel, Lima, Peru

3. Director of the OB-GYN Ultrasound Unit, Lis Maternity Hospital. Tel Aviv Medical Center, Israel

The evaluation of the fetal brain is an essential point in obstetric ultrasound due to the large number of malformations that can be diagnosed. The ISUOG guide provides us with the elementary sections for the suspicion of brain pathology; but we can extend and improve our ultrasound with the visualization of easily reproducible structures, such as the anterior complex, corpus callosum, Sylvian fissure and the fourth ventricle. We present some tools to complement the assessment of the fetal brain.

Key words: Fetus; Embryonic and fetal development; Cerebrum; Corpus callosum; Cerebral aqueduct; Fourth ventricle

Introducción

Fetal brain pathologies are frequent (1-2/1 000 live births) and require in all cases a thorough assessment, not only because of their implications but also because of their long-term repercussions. Currently, the vast majority of brain malformations diagnosed during pregnancy represent gross and obvious pictures. However, many 'subtle' or 'minor' malformations - which can have serious long-term neurodevelopmental repercussions affecting the social integration of these children - are not diagnosed during routine ultrasonographic assessment.

The guidelines for routine fetal brain assessment in the second trimester1 as well as the guidelines for basic fetal brain assessment2 proposed by ISUOG (International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology), are currently limited to a transabdominal study of axial sections of the brain. But, as we will review below, the scope of this assessment has important limitations and should generally be expanded when faced with a suspicion of fetal brain pathology.

This review is not intended to be a manual of fetal brain neurosonography (broad and dedicated examination), which is performed by an expert with experience in brain pathology2, but aims to provide the operator, during the basic screening, with the basics to establish an initial diagnostic suspicion and thus be able to refer the patient to a specialized examination. We will suggest and support some tools that complement, but do not replace, what is recommended by ISUOG.

Information search methodology

We searched for original articles and reviews in the databases OVIDSP, ScienceDirect, SciELO and PUBMED, with the search terms 'fetal neurosonography', 'anterior complex', 'corpus callosum', 'Sylvian fissure', 'fourth ventricle'. The most relevant prenatal and perinatal studies in the last 5 years were selected; some older than 10 years were included due to their historical and scientific relevance.

Fetal brain assessment

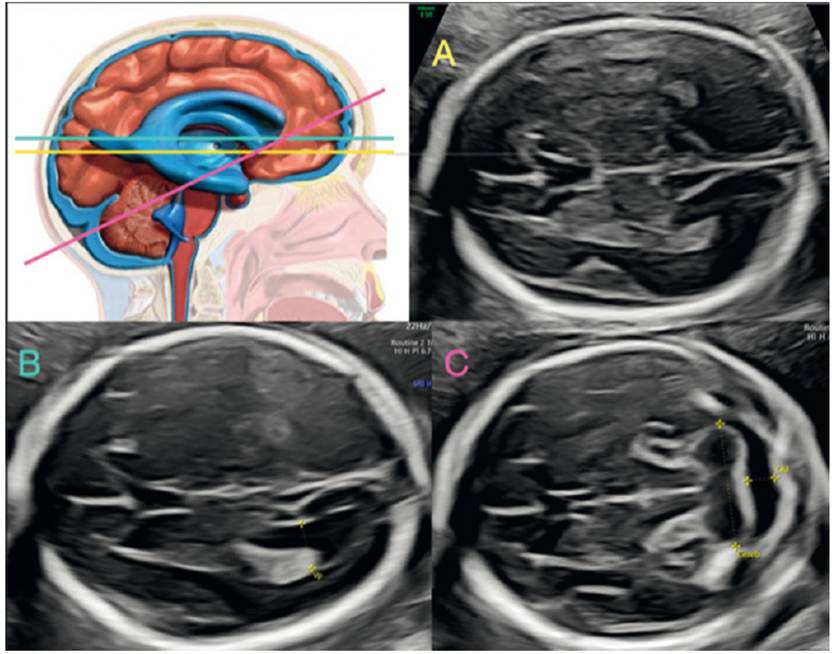

Routine assessment of the fetal brain begins with identification of the midline, shape and integrity of the skull. An essential part of this first study is the identification of brain structures such as the thalami and the cavum de septum pellucidum (CSP). Cephalic biometries -biparietal diameter and cephalic circumference -are performed, always valued in percentiles according to gestational age (transthalamic or biparietal plane) (Figures 1A and 2A).

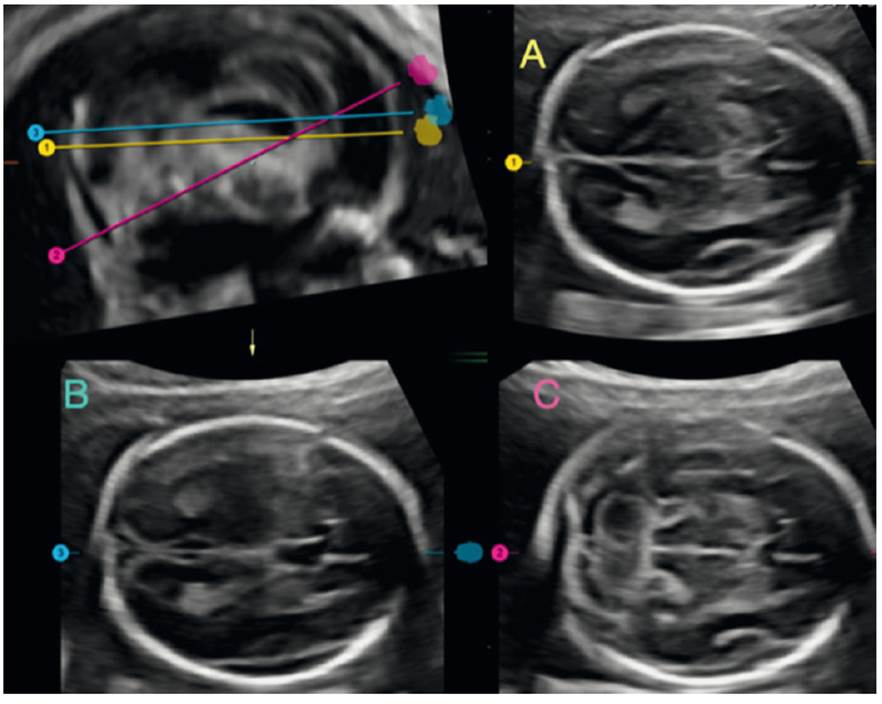

Figure 1 ISUOG recommended cuts. A: transthalamic section. B: transventricular section. C: transcerebellar section

Figure 2 Volumetric image analysis of the fetal brain, showing the level of each section recommended by ISUOG. A: transthalamic section. B: transventricular section. C: transcerebellar section.

The second brain image requires the identification of the ventricular system, especially the ventricular atrium. A plane is established in which the CSP and the anterior horns of the ventricular system are also visualized (transventricular plane). It is performed with the intention of ruling out dilatations of the cerebral ventricular system (ventriculomegaly, a very frequent sign common to many cerebral pathologies)3-10. The anatomical repairs for its correct measurement involve the identification of the parieto-occipital fissure, which marks the place where the in-to-in measurement of the walls of the ventricular atrium is performed1,2; the classic value of 9.9 mm is still maintained as the dogma of normality3-5) (Figures 1B and 2B). During the first trimester and up to week 20, this value should not be taken into account. The diagnostic suspicion is based on the qualitative assessment of the lateral ventricle and its relationship with the choroid plexus, which normally should occupy the entire width of the atrium11,12.

The third plane focuses on the posterior fossa: the cerebellum is identified and the vermis is differentiated from the cerebellar hemispheres (hyperechogenic central structure). Again, a plane is required in which the CSP and the anterior horns of the ventricular system are also visualized1,2. The cisterna magna (CM), which runs from the vermis to the internal table of the occipital bone, is measured (2 to 10 mm in the second and third trimester). Both collapse and dilatation are signs common to many pathologies of the posterior fossa and spine13,14. Likewise, the transcebellar diameter is measured (assessing its size in percentiles in relation to gestational age), which includes the hemispheres and vermis. Subjectively, the normality of the cerebellum is added by assessing the shape of its contour and the lack of 'communication' of the fourth ventricle with the cisterna magna15 (Figures 1C and 2C).

‘Anterior complex’ assessment

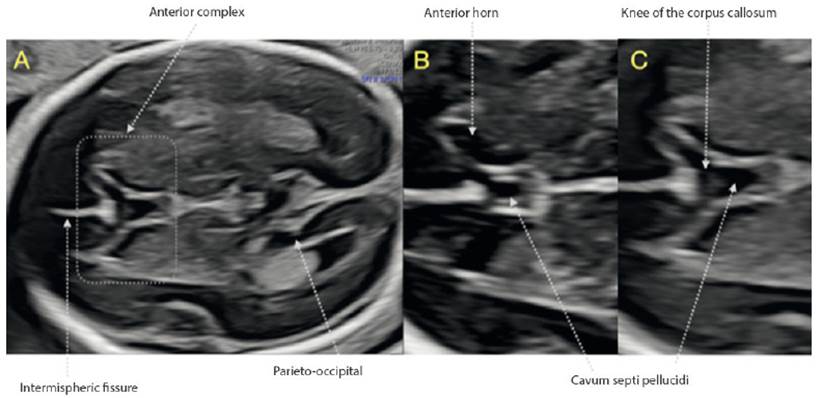

During the assessment of the brain, the identification of the CSP is a cardinal point of repair for the three sections recommended by ISUOG1,2; however, we pay little attention to the information that this structure offers us. We must begin to assess the relationship of the anterior horns of the ventricular system and the CSP, what Cagneaux and Guibaud16 termed the 'anterior complex'. In this anterior complex there are key structures that we must identify, such as the knee of the corpus callosum, the integrity of the midline and the shape of the anterior horns (Figure 3). Viñals17 describes the normal morphology of the anterior complex, making it clear that the CSP can be rectangular in shape or an anteriorly based triangle, and the anterior horns of the ventricular system look like a 'comma' or a triangle (Figure 3B and 3C).

Figure 3 Anterior complex. A: Transventricular section in which the anterior complex is displayed. B and C: Structures identified in theanterior complex. Note the difference in the normal morphology of the CSP and the anterior loops between both images.

This rapid qualitative assessment provides important information on the existence of at least a portion of the corpus callosum, and the symmetry of the ventricular system and the periventricular zone, which may be the site of cortical developmental, hemorrhagic or infectious pathology18,19. All this positions it as a tool with potential for the detection of holoprosencephaly20,21, commissural anomalies (complete agenesis of the corpus callosum, septo-preoptic dysplasia)22-28, schizencephaly29 and barotrauma (obstructive ventriculomegaly)30,31.

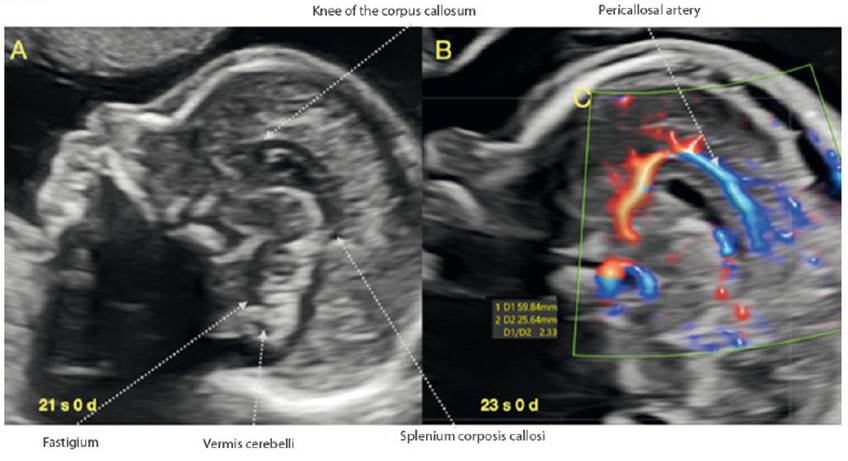

Display of the corpus callosum

Within the assessment of the fetal face recommended by ISUOG1, the fetal profile is a mandatory view, constituting a valuable opportunity for the visualization of the corpus callosum (CC) (Figure 4A). If we are in a strict sagittal section and we manage to take advantage of the metopic suture or the anterior fontanel, the visualization of the CC will generally be adequate, and we can quickly verify its presence, normal morphology and relationship with nearby structures, establishing suspicion of partial or total agenesis or dysgenesis32-38. Also, as recommended by Youssef and Pilu39, the use of Doppler could be added to facilitate visualization due to the shape of the vasculature (pericallosal arteries) (Figure 4B). If we would like to apply some simple measure beyond the direct visualization of the structure, in relation to the dimensions of the CC, we suggest assessing the relationship between the length of the corpus callosum with the anteroposterior diameter, in a sagittal section. This relationship remains constant between 3.4 and 3.8 from week 20 to term and is related to the values found in neonates40-42.

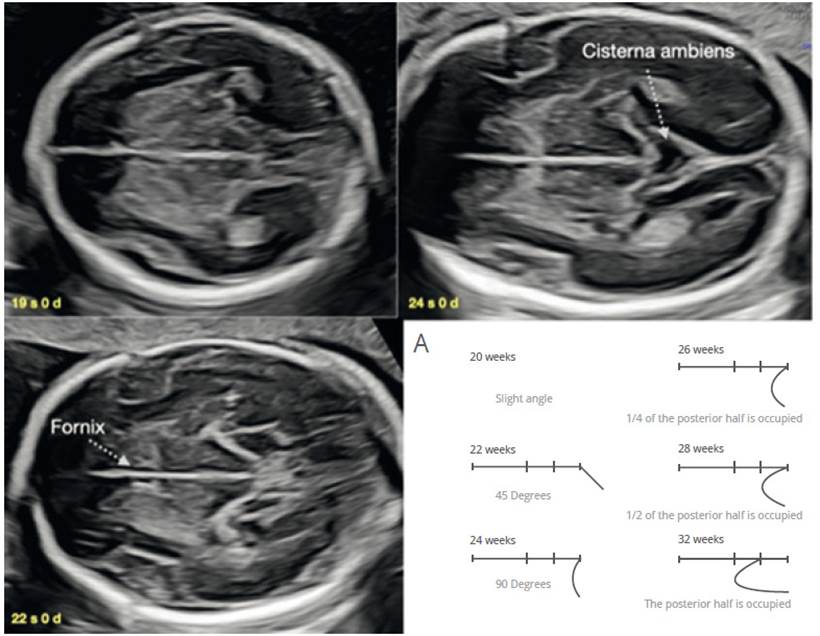

Display of the Sylvian fissure

The cerebral cortex assessment has always been a complex and systematically elusive topic43-50. When performing the assessment of the ventricular atrium, we necessarily visualize the parieto-occipital fissure as a reference point and have an intuitive idea of the correspondence of its shape with gestational age43-45. We can add to this the visualization of Sylvian fissure (CS) in an easily reproducible axial view51,52. In 2008, Quarello53 assessed in 200 fetuses the evolution of the relationship between the insula and the temporal lobe (CS operculation), from 22 to 32 weeks, and proposed a score from 0 to 10 related to gestational age. This assessment is given in an axial section, a little more caudal to the transthalamic view, in which we must achieve to display three points of standardization of the CS level: the columns of the fornix in the lower part of the CSP, third ventricle in the central part and the cisterna ambiens in the posterior part (Figure 5). Guibaud54 simplifies the CS assessment table (Figure 5A) and applies it against various brain malformations, showing that abnormal development of CS operculation is found not only in cortical malformations but also in commissural pathology, neural tube and posterior fossa defects(47,49,52.55). Therefore, the development of CS operculature is a valuable, reproducible and effective element in the suspicion of fetal brain pathology.

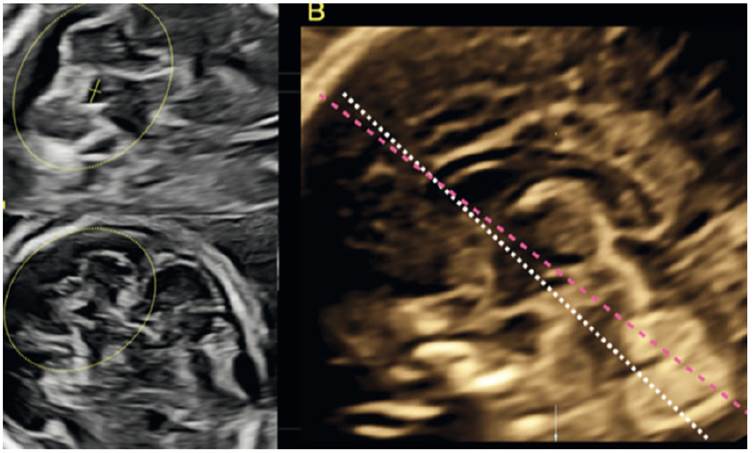

Fourth ventricle assessment

The posterior fossa assessment presents limitations, especially in cases with CM measurements less than 10 mm, since there is a tendency to assess only the presence of the superior vermis, leaving aside the alterations in position (rotation) and shape56-58. The assessment of the shape of the fourth ventricle in an axial view can give us additional information, as it is an indirect indicator of normality in the vermis and midbrain (cerebral peduncles), although sagittal assessment is ideal for an advanced assessment59-61.

In 1994, Baumeister62 described the technique for the fourth ventricle assessment in an axial section, by tilting the cut of the transcerebellar diameter until the visualization of the fourth ventricle and cerebellar hemispheres is achieved (Figures 6A and 6C). Three shapes are identified: ovoid, triangular and boomerang (Figures 6A and 6B). Quarello63 highlights the normal quadrangular shape of the fourth ventricle with the transverse diameter larger than the antero-posterior and, in cases with Joubert's syndrome, he observed that the shape of the fourth ventricle was elongated. Haratz64, based on these studies, in a prospective series of 384 normal fetuses, proposes the rapid evaluation of the fourth ventricle by the relation between the latero-lateral and antero-posterior diameter, denominating it fourth ventricle index (4VI), which is greater than 1 in normal fetuses, independent of gestational age (Figure 6A). By means of this assessment, pathologies such as Joubert's syndrome, rhomboencephalosinapsis, pontocerebellar hypoplasia and cobblestone cortical malformations could be detected65-70.

Conclusion

In fetal brain assessment during ultrasound screening, it is feasible to examine the anterior complex, corpus callosum, Sylvian fissure and fourth ventricle (not mandatory according to ISUOG guidelines). This potentially has an impact on the diagnostic suspicion of some of the main fetal neurological anomalies. These visualizations are complementary to those recommended by ISUOG and, being generally reproducible in daily clinical practice, can expand our ability to detect fetal brain pathology.

REFERENCES

1. Salomon LJ, Alfirevic Z, Berghella V, Bilardo C, Hernandez- Andrade E, Johnsen SL, et al. Practice guidelines for performance of the routine mid-trimester fetal ultrasound scan. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011;37(1):116-26. doi:10.1002/uog.8831 [ Links ]

2. Malinger G, Paladini D, Haratz KK, Monteagudo A, Pilu G, Timor-TritschIE. ISUOG Practice Guidelines (updated): sonographic examination of the fetal central nervous system. Part 1: performance of screening examination and indications for targeted neurosonography. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2020;56:476-84. Doi:10.1002/uog.22145 [ Links ]

3. Pisapia JM, Sinha S, Zarnow DM, Johnson MP, Heuer GG. Fetal ventriculomegaly: Diagnosis, treatment, and future directions. Childs Nerv Syst. 2017;33(7):1113-23. doi:10.1007/s00381-017-3441-y [ Links ]

4. Guibaud L, Lacalm A, Rault E. Fetal ventriculomegaly: diagnostic, ethical and semantic considerations. Childs Nerv Syst. 2017;33(11):1863-4. doi:10.1007/s00381-017-3500-4 [ Links ]

5. Malinger G, Lerman-Sagie T. Fetal neurology. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2018;22(6):895-7. doi:10.1016/j.ejpn.2018.11.004 [ Links ]

6. D'Antonio F, Zafeiriou DI. Fetal ventriculomegaly: What we have and what is still missing. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2018;22(6):898-9. doi:10.1016/j.ejpn.2018.11.005 [ Links ]

7. Griffiths PD, Bradburn M, Campbell MJ, Cooper Cl, Graham R, Jarvis D, et al. Use of MRI in the diagnosis of fetal brain abnormalities in utero (MERIDIAN): a multicentre, prospective cohort study. Lancet.2017;389(10068):538-46. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31723-8 [ Links ]

8. Paladini D, Malinger G, Pilu G, Timor-Trisch I, Volpe P. The MERIDIAN trial: caution is needed. Lancet. 2017;389(10084):2103. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31337-5 [ Links ]

9. Carta S, Kaelin Agten A, Belcaro C, Bhide A. Outcome of fetuses with prenatal diagnosis of isolated severe bilateral ventriculomegaly: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2018;52(2):165-73. doi:10.1002/uog.19038 [ Links ]

10. Scala C, Familiari A, Pinas A, Papageordhiou AT, Bhide A, TGhilaganathan B, Khalil A. Perinatal and long-term outcomes in fetuses diagnosed with isolated unilateral ventriculomegaly: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2017;49(4):450-9. doi:10.1002/uog.15943 [ Links ]

11. Manegold-Brauer G, Oseledchyk A, Floeck A, Berg C, Gembruch U, Geipel A. Approach to the sonographic evaluation of fetal ventriculomegaly at 11 to 14 weeks gestation. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16(12):3. doi:10.1186/s12884-016-0797-z [ Links ]

12. Chaoui R, Benoit B, Entezami M, Frenzel W, Heling KS, Ladendorf B, et al. Ratio of fetal choroid plexus to head size: simple sonographic marker of open spina bifida at 11-13 weeks gestation. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2020;55(1):81- 6. doi:10.1002/uog.20856 [ Links ]

13. Wüest A, Surbek D, Wiest R, Weisstanner C, Bonel H, Steinlin M, Raio L, Tutschek B. Enlarged posterior fossa on prenatal imaging: differential diagnosis, associated anomalies and postnatal outcome. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2017;96(7):837-43. doi:10.1111/aogs.13131 [ Links ]

14. Garel C. Posterior fossa malformations: main features and limits in prenatal diagnosis. Pediatr Radiol. 2010;40(6):1038- 45. doi:10.1007/s00247-010-1617-7 [ Links ]

15. Leibovitz Z, Guibaud L, Garel C, Massoud M, Karl K, Malinger G, et al. The cerebellar "tilted telephone receiver sign" enables prenatal diagnosis of PHACES syndrome. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2018;22(6):900-9. doi:10.1016/j.ejpn.2018.08.006 [ Links ]

16. Cagneaux M, Guibaud L. From cavum septi pellucidi to anterior complex: how to improve detection of midline cerebral abnormalities. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;42(4):485-6. doi:10.1002/uog.12505 [ Links ]

17. Viñals F, Correa F, Gonçalves-Pereira PM. Anterior and posterior complexes: a step towards improving neurosonographic screening of midline and cortical anomalies. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2015;46(5):585-94. doi:10.1002/uog.14735 [ Links ]

18. Levy M, Lev D, Leibovitz Z, Kashanian A, Gindes L, Tamarkin M, et al. Periventricular pseudocysts of noninfectious origin: Prenatal associated findings and prognostic factors. Prenat Diagn. 2020;40(8):931-41. doi:10.1002/pd.5704 [ Links ]

19. Khalil A, Sotiriadis A, Chaoui R, da Silva Costa F, D'Antonio F, Heath PT, et al. ISUOG Practice Guidelines: role of ultrasound in congenital infection. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2020;56(1):128-51. doi:10.1002/uog.21991 [ Links ]

20. Winter TC, Kennedy AM, Woodward PJ. Holoprosencephaly: a survey of the entity, with embryology and fetal imaging. Radiographics. 2015;35(1):275-90. doi:10.1148/rg.351140040 [ Links ]

21. Malinger G, Lev D, Kidron D, Heredia F, Hershkovitz R, Lerman-Sagie T. Differential diagnosis in fetuses with absent septum pellucidum. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2005;25(1):42-9. doi:10.1002/uog.1787 [ Links ]

22. Malinger G, Lev D, Oren M, Lerman-Sagie T. Non-visualization of the cavum septi pellucidi is not synonymous with agenesis of the corpus callosum. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2012;40(2):165-70. doi:10.1002/uog.11206 [ Links ]

23. Borkowski-Tillman T, Garcia-Rodriguez R, Viñals F, Branco M, Kradjen-Haratz K, Ben-Sira L, et al. Agenesis of the septum pellucidum: Prenatal diagnosis and outcome. Prenat Diagn. 2020;40(6):674-80. doi:10.1002/pd.5663 [ Links ]

24. Ben M'Barek I, Tassin M, Guët A, Simon I, Mandelbrot L, Ponce O. Antenatal diagnosis of absence of septum pellucidum. Clin Case Rep. 2020;8(3):498-503. doi:10.1002/ccr3.2666 [ Links ]

25. Sundarakumar DK, Farley SA, Smith CM, Maravilla KR, Dighe MK, Nixon JN. Absent cavum septum pellucidum: a review with emphasis on associated commissural abnormalities. Pediatr Radiol. 2015;45(7):950-64. doi:10.1007/s00247-015-3318-8 [ Links ]

26. Maduram A, Farid N, Rakow-Penner R, Ghassemi N, Khanna PC, Robbins SL, Hull A, Gold J, Pretorius DH. Fetal ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging findings in suspected septo- optic dysplasia: a diagnostic dilemma. J Ultrasound Med. 2020;39(8):1601-14. doi:10.1002/jum.15252 [ Links ]

27. Pilliod RA, Pettersson DR, Gibson T, Gievers L, Kim A, Schaey R, Oh KY, Shaffer BI. Diagnostic accuracy and clinical outcomes associated with prenatal diagnosis of fetal absent cavum septi pellucidi. Prenat Diagn. 2018;38(6):395-401. doi:10.1002/pd.5247 [ Links ]

28. Paladini D, Birnbaum R, Donarini G, Maffeo I, Fulcheri E. Assessment of fetal optic chiasm: an echoanatomic and reproducibility study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;48(6):727- 32. doi:10.1002/uog.17227 [ Links ]

29. Braga VL, da Costa MDS, Riera R, Dos Santos Rocha LP, de Oliveira Santos BF, Matsumura Hondo TT, et al. Schizencephaly: A review of 734 patients. Pediatr Neurol. 2018;87:23-9. doi:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2018.08.001 [ Links ]

30. Rault E, Lacalm A, Massoud M, Massardier J, Di Rocco F, Gaucherand P, Guibaud L. The many faces of prenatal imaging diagnosis of primitive aqueduct obstruction. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2018;22(6):910-8. doi:10.1016/j.ejpn.2018.07.015 [ Links ]

31. Kline-Fath BM, Arroyo MS, Calvo-Garcia MA, Horn PS, Thomas C. Congenital aqueduct stenosis: Progressive brain findings in utero to birth in the presence of severe hydrocephalus. Prenat Diagn. 2018;38(9):706-12. doi:10.1002/pd.5317 [ Links ]

32. Malinger G, Lev D, Lerman-Sagie T. The fetal corpus callosum. 'The truth is out there'. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;30(2):140-41. doi:10.1002/uog.4095 [ Links ]

33. Lerman-Sagie T, Ben-Sira L, Achiron R, L Schreiber, G Hermann, D Lev, et al. Thick fetal corpus callosum: an ominous sign? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2009;34(1):55-61. doi:10.1002/uog.6356 [ Links ]

34. Kidron D, Shapira D, Ben Sira L, Malinger G, Lev D, Cioca A, Sharony R, Lerman Sagie T. Agenesis of the corpus callosum. An autopsy study in fetuses. Virchows Arch. 2016;468(2):219-30. doi:10.1007/s00428-015-1872-y [ Links ]

35. Shinar S, Har-Toov J, Lerman-Sagie T, Malinger G. Thick corpus callosum in the second trimester can be transient and is of uncertain significance. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;48(4):452-7. doi:10.1002/uog.15678 [ Links ]

36. Masmejan S, Blaser S, Keunen J, Seaward G, Windrim R, Kelly E, Ryan G, Baud D, Van Mieghem T. Natural history of ventriculomegaly in fetal agenesis of the corpus callosum. J Ultrasound Med. 2020;39(3):483-8. doi:10.1002/jum.15124 [ Links ]

37. Karl K, Esser T, Heling KS, Chaoui R. Cavum septi pellucidi (CSP) ratio: a marker for partial agenesis of the fetal corpus callosum. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2017;50(3):336-41. doi:10.1002/uog.17409 [ Links ]

38. Schupper A, Konen O, Halevy A, Cohen R, Aharoni S, Shuper A. Thick corpus callosum in children. J Clin Neurol. 2017;13(2):170-4. doi:10.3988/jcn.2017.13.2.170 [ Links ]

39. Youssef A, Ghi T, Pilu G. How to image the fetal corpus callosum. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;42(6):718-20. doi:10.1002/uog.12367 [ Links ]

40. Malinger G, Zakut H. The corpus callosum: normal fetal development as shown by transvaginal sonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1993;161(5):1041-3. doi:10.2214/ajr.161.5.8273605 [ Links ]

41. Tepper R, Leibovitz Z, Garel C, Sukenik-Halevy R. A new method for evaluating short fetal corpus callosum. Prenat Diagn. 2019;39(13):1283-90. doi:10.1002/pd.5598 [ Links ]

42. Gao Y, Yan K, Yang L, Cheng G, Zhou W. Biometry reference range of the corpus callosum in neonates: An observational study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(24):e11071. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000011071 [ Links ]

43. Cohen-Sacher B, Lerman-Sagie T, Lev D, Malinger G. Sonographic developmental milestones of the fetal cerebral cortex: a longitudinal study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2006;27(5):494-502. doi:10.1002/uog.2757 [ Links ]

44. Toi A, Lister WS, Fong KW. How early are fetal cerebral sulci visible at prenatal ultrasound and what is the normal pattern of early fetal sulcal development? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2004;24(7):706-15. doi:10.1002/uog.1802 [ Links ]

45. Pistorius LR, Stoutenbeek P, Groenendaal F, de Vries L, Manten G, Mulder E, Visser G. Grade and symmetry of normal fetal cortical development: a longitudinal two- and three-dimensional ultrasound study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010;36(6):700-8. doi:10.1002/uog.7705 [ Links ]

46. Malinger G, Kidron D, Schreiber L, Ben-Sira L, Hoffmann C, Lev D, et al. Prenatal diagnosis of malformations of cortical development by dedicated neurosonography. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;29(2):178-91. doi:10.1002/uog.3906 [ Links ]

47. Malinger G, Lev D, Lerman-Sagie T. Abnormal sulcation as an early sign for migration disorders. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2004;24(7):704-5. doi:10.1002/uog.1795 [ Links ]

48. Chen X, Li SL, Luo GY, Norwitz ER, Ouyand S-Y, Wen H-X, et al. Ultrasonographic characteristics of cortical sulcus development in the human fetus between 18 and 41 weeks of gestation. Chin Med J (Engl). 2017;130(8):920-8. doi:10.4103/0366-6999.204114 [ Links ]

49. Pooh RK, Machida M, Nakamura T, Uenishi K, Chiyo H, Itoh K, et al. Increased Sylvian fissure angle as early sonographic sign of malformation of cortical development. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2019;54(2):199-206. doi:10.1002/uog.20171 [ Links ]

50. Poon LC, Sahota DS, Chaemsaithong P, Nakamura T, Machida M, et al. Transvaginal three-dimensional ultrasound assessment of Sylvian fissures at 18-30 weeks' gestation. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2019;54(2):190-8. doi:10.1002/uog.20172 [ Links ]

51. Lerman-Sagie T, Malinger G. Focus on the fetal Sylvian fissure. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008;32(1):3-4. doi:10.1002/uog.5398 [ Links ]

52. Guibaud L, Lacalm A. Etiological diagnostic tools to elucidate 'isolated' ventriculomegaly. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2015;46(1):1-11. doi:10.1002/uog.14687 [ Links ]

53. Quarello E, Stirnemann J, Ville Y, Guibaud L. Assessment of fetal Sylvian fissure operculization between 22 and 32 weeks: a subjective approach. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008;32(1):44-9. doi:10.1002/uog.5353 [ Links ]

54. Guibaud L, Selleret L, Larroche JC, Buenerd A, Alias F, Gaucherand P, et al. Abnormal Sylvian fissure on prenatal cerebral imaging: significance and correlation with neuropathological and postnatal data. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008;32(1):50-60. doi:10.1002/uog.5357 [ Links ]

55. Ben-Sira L, Garel C, Malinger G, Constantini S. Prenatal diagnosis of spinal dysraphism. Childs Nerv Syst. 2013;29(9):1541-52. doi:10.1007/s00381-013-2178-5 [ Links ]

56. Malinger G, Lev D, Lerman-Sagie T. The fetal cerebellum. Pitfalls in diagnosis and management. Prenat Diagn. 2009;29(4):372-80. doi:10.1002/pd.2196 [ Links ]

57. Guibaud L, des Portes V. Plea for an anatomical approach to abnormalities of the posterior fossa in prenatal diagnosis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2006;27(5):477-81. doi:10.1002/uog.2777 [ Links ]

58. Lerman-Sagie T, Prayer D, Stöcklein S, Malinger G. Fetal cerebellar disorders. Handb Clin Neurol. 2018;155:3-23. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-64189-2.00001-9 [ Links ]

59. Leibovitz Z, Haratz KK, Malinger G, Shapiro I, Pressman C. Fetal posterior fossa dimensions: normal and anomalous development assessed in mid-sagittal cranial plane by three-dimensional multiplanar sonography. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2014;43(2):147-53. doi:10.1002/uog.12508 [ Links ]

60. Leibovitz Z, Shkolnik C, Haratz KK, Malinger G, Shapiro I, Lerman-Sagie T. Assessment of fetal midbrain and hindbrain in mid-sagittal cranial plane by three-dimensional multiplanar sonography. Part 1: comparison of new and established nomograms. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2014;44(5):575-80. doi:10.1002/uog.13308 [ Links ]

61. Leibovitz Z, Shkolnik C, Haratz KK, Malinger G, Shapiro I, Lerman-Sagie T. Assessment of fetal midbrain and hindbrain in mid-sagittal cranial plane by three-dimensional multiplanar sonography. Part 2: application of nomograms to fetuses with posterior fossa malformations. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2014;44(5):581-7. doi:10.1002/uog.13312 [ Links ]

62. Baumeister LA, Hertzberg BS, McNally PJ, Kliewer MA, Bowie JD. Fetal fourth ventricle: US appearance and frequency of depiction. Radiology. 1994;192(2):333-6. doi:10.1148/radiology.192.2.8029392 [ Links ]

63. Quarello E, Molho M, Garel C, Couture A, Legac MP, Moutard ML,et al. Prenatal abnormal features of the fourth ventricle in Joubert syndrome and related disorders. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2014;43(2):227-32. doi:10.1002/uog.12567 [ Links ]

64. Haratz KK, Shulevitz SL, Leibovitz Z, Lev D, Shalev J, Tomarkin M, et al. Fourth ventricle index: sonographic marker for severe fetal vermian dysgenesis/agenesis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2019;53(3):390-5. doi:10.1002/uog.19034 [ Links ]

65. Parisi MA. The molecular genetics of Joubert syndrome and related ciliopathies: The challenges of genetic and phenotypic heterogeneity. Transl Sci Rare Dis. 2019;4(1-2):25-49. doi:10.3233/TRD-190041 [ Links ]

66. Poretti A, Boltshauser E. Fetal diagnosis of rhombencephalosynapsis. Neuropediatrics. 2015;46(6):357-8. doi:10.1055/s-0035-1566754 [ Links ]

67. Desai S, Desai T. Prenatal diagnosis of pontocerebellar hypoplasia associated with rare syndromes: Expanding the genetic and phenotypic spectrum. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2021;57(3):498-9. doi: 10.1002/uog.22038. [ Links ]

68. Lacalm A, Nadaud B, Massoud M, Putoux A, Gaucherand P, Guibaud L. Prenatal diagnosis of cobblestone lissencephaly associated with Walker-Warburg syndrome based on a specific sonographic pattern. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;47(1):117-22. doi:10.1002/uog.15735 [ Links ]

69. Lerman-Sagie T, Leibovitz Z. Malformations of cortical development: From postnatal to fetal imaging. Can J Neurol Sci. 2016;43(5):611-8. doi:10.1017/cjn.2016.27 [ Links ]

70. Pertl B, Eder S, Stern C, Verheyen S. The fetal posterior fossa on prenatal ultrasound imaging: normal longitudinal development and posterior fossa anomalies. Ultraschall Med. 2019;40(6):692-721. doi:10.1055/a-1015-0157 [ Links ]

Received: June 20, 2021; Accepted: August 06, 2021

text in

text in