Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista Peruana de Ginecología y Obstetricia

versión On-line ISSN 2304-5132

Rev. peru. ginecol. obstet. vol.68 no.4 Lima oct./dic 2022 Epub 30-Nov-2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.31403/rpgo.v68i2460

Case report

Ectopic pregnancy in a previous cesarean scar

1. Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Hospital de Hellín, Albacete, Spain

Ectopic pregnancies in the scar of previous cesarean section are an infrequent pathology. They represent the rarest form of ectopic gestation and occur in 1 in 2.000 pregnancies. In recent decades there has been an increase in its incidence related to the increase in the number of cesarean sections. Its inconsistent clinical presentation may delay its diagnosis, so it requires a high degree of suspicion for its identification. The diagnosis is mainly made with transvaginal ultrasound, by finding of the gestational sac in the hysterotomy scar. The scarcity of cases reported in the literature makes it impossible to standardize correct treatment. The insufficient information available together with the potential serious complications make this pathology a challenge for every specialist. We present a case of ectopic pregnancy in the scar of a previous cesarean section which was diagnosed ultrasonographically and resolved with medical treatment with methotrexate. The importance of followup, both clinical and with ultrasound and βhCG levels until complete resolution, is evident.

Key words: Pregnancy; ectopic; Cesarean section; Scar; Methotrexate

Introduction

Cesarean scar pregnancy (CSP) is a rare pathology1,2 that can lead to serious complications. Its anodyne clinical presentation together with the difficulty of its identification may delay its diagnosis. Currently, there is no standardized management protocol, so its finding remains a great challenge for every specialist. We present a case of CSP managed by multiple doses of methotrexate (MTX) together with a review of the published literature.

Case report

A 30-year-old woman attended the gynecology emergency department of our hospital due to vaginal bleeding and a positive home pregnancy test. When taking anamnesis, she had no personal or family history of interest. As gynecological-obstetric history, she had a previous pregnancy that ended by cesarean section due to breech presentation, in June 2020, with a normal puerperium. She said her last menstrual period had been 4 weeks and 3 days earlier.

The patient was hemodynamically stable and the general examination was normal. The gynecological examination showed a closed endocervical canal, scarce hematic debris in the vagina and absence of active bleeding. Transvaginal ultrasound was performed with the finding of 12 mm decidualized endometrium and absence of intra or extrauterine gestational sac. Beta-human chorionic gonadotropin hormone (βhCG) was requested and the result was 207 IU/L. The patient was reevaluated in 48 hours with no clinical or ultrasound change, but βhCG increased to 409 IU/L.

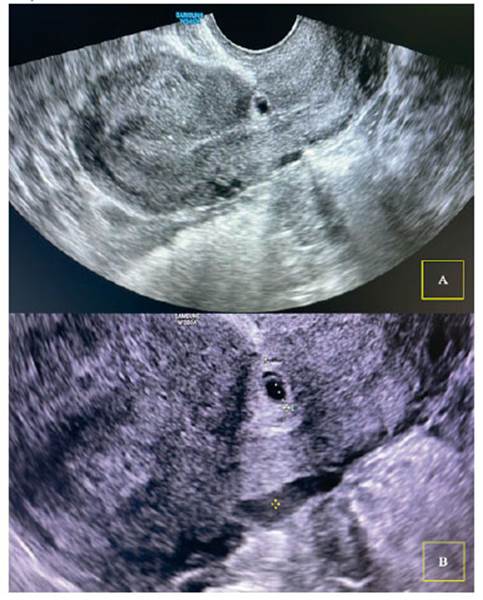

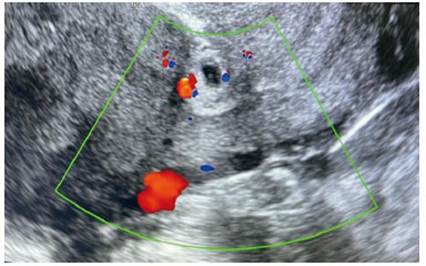

On the 6th day, the βhCG was 2,097 IU/L. A new ultrasound study was performed with visualization of the cervical canal and uterine cavity with out contents and at the level of the scar of the previous cesarean section an image compatible with a gestational sac of 24 x 18 mm, without the presence of yolk vesicle or embryonic pole inside (Figure 1). The Doppler mode showed a positive color map (Figure 2). The adnexa were normal and no free fluid was seen.

Figure 1 Transvaginal ultrasound. A) Sagitt al section with finding of type 1 ectopic pregnancy in a cesarean section scar. B) Enlargement of the previous image to measure the gestational sac (24 x 18 mm).

Figure 2 Transvaginal ultrasound with Doppler mode. Positive color map is seen around the gestational sac.

Given the high suspicion of pregnancy in a previous cesarean scar, treatment with medical management was indicated. A single dose of intramuscular methotrexate was administered at a dose of 50 mg/m2 body surface area, corresponding to 95 mg, with correct tolerance. Between the fourth and seventh post-treatment day, the patient showed a decrease in βhCG of more than 15% (17.7%). However, given the persistence of the ultrasound image, it was decided to administer a second dose of intramuscular MTX 95 mg. In the subsequent controls, the patient was asymptomatic and the βhCG values showed a progressive decrease, becoming negative ten weeks after the administration of the second dose of MTX. In addition, the control ultrasound showed the involution of the gestational sac over the cesarean scar (Figure 3).

Discussion

Ectopic pregnancy in a previous cesarean scar is rare1,2 and is defined as the implantation of the gestational sac in the scar zone of a previous hysterotomy. It occurs in approximately 1 in every 2,000 pregnancies1 and represents 0.4%2 and up to 6% of ectopic gestations in a patient with a history of cesarean section3. The first reported case was in 19784 and since then its incidence has been increasing in relation to the increase in the number of cesarean sections5.

The pathophysiology is not fully understood. It is believed that after an invasive procedure on the uterine cavity (cesarean section, uterine curettage or entry into the cavity after myomectomy) there would be an injury to the myometrium and subsequent poor healing could allow incorrect implantation of the embryo6. Thus, the gestational sac would be surrounded by myometrium and scar tissue and separated to a greater or lesser extent from the endometrial cavity.

It could also be due to the creation of fistulas between the endometrial cavity and the scar, which would lead to incorrect implantation7. However, as the initial trophoblast behaves mainly in an invasive manner, a pre-existing tract should not be necessary6. Another possible cause could be hypoxia during implantation and subsequent placental development. In vitro work has shown that different degrees of hypoxia cause cytotrophoblast cells to proliferate or invade, thus regulating the growth and architecture of the placenta8. The importance of hypoxia during placentation has led to theorize that scar areas, having abundant fibrotic tissue, will have more hypoxia which would lead to abnormalities in placentation, such as placenta accreta or placenta previa, or incorrect implantation of the embryo on the scar6. The combination of both theories would explain the increased incidence of these pathologies in patients with previous cesarean section.

At present, two types of ectopic gestations on a cesarean scar have been identified that could constitute a continuous pathology. In type I, implantation occurs on a properly healed scar and the gestation grows into the uterine cavity. And in type II, implantation occurs on a dehiscent scar or with a niche, and trophoblastic infiltration can occur towards the uterine serosa, with risk of uterine rupture and intense hemorrhage2,3. In our patient, we consider that an ectopic gestation occurred on a previous type I scar.

It seems clear that cesarean section increases its incidence, but, on the contrary, repeated cesarean sections do not seem to increase this risk9,10. In addition, other risk factors have been proposed, such as other previous uterine surgeries (uterine curettage, endometrial ablation), manual removal of the placenta, in vitro fertilization techniques11.

Diagnosis is usually at an early gestational age, around 7 weeks12. The main reason for consultation is usually vaginal bleeding or, more rarely, abdominal pain, although some authors have reported a diagnosis rate of CSP in asymptomatic patients that varies between 37-45%12. On the other hand, this pathology can also present as an emergency the patient presents with hemorrhage or uterinerupture that can lead to major complications such as heavy bleeding, hemoperitoneum and shock and requires immediate treatment13. Therefore, the high suspicion of this pathology is very important for early diagnosis and management to avoid serious complications. In our case the patient presented with vaginal bleeding without pelvic pain and a positive home pregnancy test.

The initial assessment of this pathology can be complicated, with cervical ectopic gestation and ongoing abortion being differential diagnoses. The main form of exploration has been by transvaginal ultrasound. The definition of clear diagnostic criteria is important for its early identification and, classically, they have been defined by Timor-Tristsch et al.13 The presence of embryonic button or cardiac activity facilitates the diagnosis, but its absence does not exclude it. The diagnostic criteria can be summarized as follows:

1. Visualization of empty uterine cavity and endocervical canal.

2. Finding of placenta and/or gestational sac in the hysterotomy scar.

3. Thin myometrial plane between the gestational sac and the bladder (1-3 mm) or absent.

4. Enhanced Doppler pattern around or in the area of the cesarean scar.

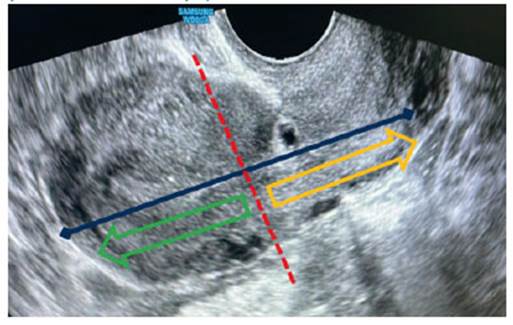

In addition, in early cases between 5-10 weeks, there may be a high degree of confusion between cases of CSP and viable low implantation intrauterine gestation. For differential diagnosis, Timor-Tristsch et al. suggest making a line that covers the total hysterometry in a sagittal section (from the uterine fundus to the cervix) and dividing this line in half. If the gestational sac remains between this midpoint and the fundus, it would be a low implantation gestation, and if it remains between the midpoint and the cervix, it would be suggestive of CSP or in rare cases a cervical ectopic11 (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Transvaginal ultrasound with sagitt al section of the uterus. In this image the criteria for the diagnosis of cesarean scar pregnancy (CSP) are applied: 1) empty uterine cavity and endocervical canal, 2) finding of gestational sac in the hysterotomy scar, 3) minimal plane of separation between the gestational sac and the bladder and 4) increased Doppler patt ern (Figure 2). In addition, by dividing the uterus into two halves, the image compatible with the gestational sac would be between the midpoint and the cervix (yellow arrow area), which would orient the CSP.

The serious complications that can occur with a late diagnosis explain the high degree of suspicion that we should have with this pathology. In case of doubts after an ultrasound study, we should extend it by requesting an MRI1.

The publications on the management of CSP are summaries of a series of few cases, making it difficult to create standardized management protocols14. Furthermore, we must remember that this pathology, even if we initiate correct treatment, presents a very high rate of complications (around 44%)15 which can be serious, requiring hysterectomy, laparotomy or embolization of the uterine arteries. Among the treatment options for CSP are expectant management, medical or surgical1,11,13,14. Treatment must be individualized, assessing the maternal condition for its hemodynamic stability, the size of the sac and the presence or not of the embryo, the presence of cardiac activity, gestational age, degree of myometrial invasion, the patient's desire for pregnancy and the capacity and experience of each team3.

The high rate of complications in the face of expectant management (risk of uterine rupture and severe hemorrhage) with potential maternal mortality does not justify expectant management, regardless of the type14. Classically, medical treatment with methotrexate (50 mg/ m2 body surface area) has been reserved for cases of CSP with an βhCG value below 5,000 mIU/mL1-3. However, the risk of complications in the face of surgical management has encouraged clinical protocols to advise its use despite higher βhCG levels2,9. The success rate of MTX therapy may be lower compared to surgical treatments and will sometimes require an additional invasive procedure11,14. To avoid this, some authors suggest the use of multiple doce MTX therapy, considering it a safe and effective management2,16. Other authors recommend intrasaccular injection of ultrasound-guided MTX, expecting slow resolution of ectopic gestation with βhCG monitoring up to 140 days after the initial MTX injection. Other doctors recommend intrasaccular injection of potassium chloride (5 mg) into the gestational sac when cardiac activity is present11.

Surgical treatment has a success rate of 96%1,14,17. It is the definitive treatment option and provides the possibility of repairing the uterine defect. There are different surgical access options - laparotomy, laparoscopy or hysteroscopy -which will depend on the experience of the surgical team11,14. Some authors advise performing an ultrasound-guided aspiration curettage in CSP type 1 and a myometrial thickness between the gestational sac and the bladder greater than 2 mm2. Evacuative curettage is not recommended due to the high failure rate of the technique and the high rate of uterine rupture and associated massive bleeding3.

In the case of our patient, given our limited experience in these types of cases, we opted for management with medical treatment, given the high possibility of complications with the surgical approach. After the administration of systemic MTX, a punctual increase in the βhCG value was observed, followed by a progressive decrease and involution of the gestational sac. The patient tolerated the treatment correctly without any complications. Although the follow-up of ectopic resolution and βhCG decrease took 82 days, the option of medical treatment with multiple doses of MTX appears to be a safe and effective treatment.

The risk of CSP recurrence is low, between 3 and 5%9. Despite the low risk of recurrence, patients with gestational desire should be informed of the potential serious complications with a new pregnancy. To the risk of recurrence of this pathology must be added the risk of uterine rupture or massive hemorrhage, even with an intrauterine pregnancy.

In conclusion, ectopic pregnancy in a previous cesarean scar is a rare pathology, but with potentially serious maternal risks. Its high degree of suspicion together with well-defined diagnostic criteria may allow its early diagnosis and management. The few cases reported in the literature do not allow establishing a standardized treatment and this must be individualized by assessing the maternal condition for its hemodynamic stability, the size of the sac and the presence or not of the embryo, as well as cardiac activity, gestational age, degree of myometrial invasion, the patient's desire for pregnancy and the capacity for action and experience of each team.

REFERENCES

1. Elson CJ, Salim R, Potdar N, Chetty M, Ross JA, Kirk EJ. Diagnosis and Management of Ectopic Pregnancy. BJOG. 2016;123(13):e15-55. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.14189 [ Links ]

2. Cobo T, Escura S, Ferrero S, Creus M, López M, Palacio M. Protocolo: Gestación Ectópica Tubárica y No Tubárica. Protocolo de Medicina Maternofetal Hospital Clinic de Barcelona. 2018; Disponible en: https://medicinafetalbarcelona.org/ protocolos/es/patologia-materna-obstetrica/gestacion-ectopica.html [ Links ]

3. Ferri B, Padilla P, Hidalgo JJ, Aznar I, Roig S, Domingo S. Embarazo Ectópico sobre cicatriz de cesárea. Diagn Prenat. 2013;24(4):166-9. doi:10.1016/j.diapre.2013.02.001 [ Links ]

4. Akhanoba F, Awala A, Boret, T. Caesarean Scar Ectopic Pregnancies-Case Series from a District General Hospital. Open J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;7:608-15. doi:10.4236/ojog.2017.75063 [ Links ]

5. Miseljic N, Basic E, Miseljic S. Causes of an Increased Rate of Caesarean Section. Mater Sociomed. 2018;30(4):287-9. doi:10.5455/msm.2018.30.287-289 [ Links ]

6. Rosen T. Placenta Accreta and Cesarean Scar Pregnancy: Overlooked Costs of the Rising Cesarean Section Rate. Clin Perinatol. 2008;35(3):519-29. doi:10.1016/j.clp.2008.07.003 [ Links ]

7. Fylstra DL. Ectopic pregnancy within a cesarean scar: a review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2002;57(8):537-43. doi:10.1097/00006254-200208000-00024 [ Links ]

8. Genbacev O, Zhou Y, Ludlow JW, Fisher SJ. Regulation of human placental development by oxygen tension. Science. 1997;277(5332):1669-72. doi:10.1126/science.277.5332.1669 [ Links ]

9. Hancerliogullari N, Yaman S, Aksoy RT, Tokmak A. Does an increased number of cesarean sections result in greater risk for mother and baby in low-risk, late preterm and term deliveries? Pak J Med Sci. 2019;35(1):10-6. doi:10.12669/pjms.35.1.364 [ Links ]

10. Jayaram PM, Okunoye GO, Konje J. Caesarean scar ectopic pregnancy: diagnostic challenges and management options. TOG. 2017;19(1):13-20. doi:10/1111/tog.12355 [ Links ]

11. Timor-Tritsch IE. Cesarean Scar pregnancy. Uptodate. 2022:1-38. [ Links ]

12. Rotas MA, Haberman S, Levgur M. Cesarean scar ectopic pregnancies: etiology, diagnosis, and management. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(6):1373-81. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000218690.24494.ce [ Links ]

13. Timor-Tritsch IE, Monteagudo A, Santos R, Tsymbal T, Pineda G, Arslan AA. The diagnosis, treatment, and follow- up of cesarean scar pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207(1):44.e1-13. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2012.04.018 [ Links ]

14. Glenn TL, Bembry J, Findley AD, Yaklic JL, Bhagavath B, Gagneux P, et al. Cesarean Scar Ectopic Pregnancy: Current Management Strategies. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2018;73(5):293-302. doi:10.1097/OGX.0000000000000561 [ Links ]

15. Timor-Tritsch IE, Monteagudo A. Unforeseen consequences of the increasing rate of cesarean deliveries: early placenta accreta and cesarean scar pregnancy. A review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207(1):14-29. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2012.03.007 [ Links ]

16. Kutuk MS, Uysal G, Dolanbay M, Ozgun MT. Successful medical treatment of cesarean scar ectopic pregnancies with systemic multidose methotrexate: single-center experience. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2014;40(6):1700-6. doi:10.1111/jog.12414 [ Links ]

17. Maheux-Lacroix S, Li F, Bujold E, Nesbitt-Hawes E, Deans R, Abbott J. Cesarean Scar Pregnancies: A Systematic Review of Treatment Options. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24(6):915-25. doi:10.1016/jmig.2017.05.019 [ Links ]

Received: March 21, 2022; Accepted: October 04, 2022

texto en

texto en