Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Revista Peruana de Ginecología y Obstetricia

On-line version ISSN 2304-5132

Rev. peru. ginecol. obstet. vol.69 no.2 Lima Apr./Jun. 2023 Epub July 06, 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.31403/rpgo.v69i2523

Case report

Isolated mild fetal ventriculomegaly. Report of a case

1 Hospital de Hellín, Albacete, Spain

Ventriculomegaly is a marker of abnormal brain development and is a cause for concern when present. It has a prevalence of 0.3-1/1000 live births and is more frequent in male fetuses. Ventriculomegaly is defined as the atrioventricular diameter of the lateral ventricles greater than or equal to 10 mm. A measurement of 10-15 mm constitutes mild ventriculomegaly while values >15 mm constitute severe ventriculomegaly. Ventriculomegaly may be isolated or associated with other anomalies including abnormal structural findings, chromosomal abnormalities or prenatal infections in about 50-84% of cases. If ventriculomegaly is mild and isolated, the most frequent outcome is normal. Survival of newborns with isolated mild ventriculomegaly is high, with reports of 93-98%. The probability of normal neurodevelopment is greater than 90% and will not be different from that of the general population. Therefore, in the presence of isolated mild ventriculomegaly, after a complete evaluation, the pregnant woman should be informed that the prognosis is favorable, and that the child will probably be considered normal. We present a case of isolated mild left ventriculomegaly detected in the prenatal ultrasound at 20 weeks, who underwent serial neurosonographic controls, genetic amniocentesis and study of prenatal infections, the latter two being normal and showing resolution of ventriculomegaly, as well as postpartum control within the limits of normality.

Key words: fetal ventriculomegaly; prenatal diagnosis

Introduction

Ventriculomegaly is one of the most frequent abnormal diagnoses of the fetal central nervous system (CNS). It is defined as an increase in the size of the lateral ventricular atrium. The diagnosis is based on the reference ranges established by Cardoza et al. in 1988, in which the upper limit of the lateral ventricular size does not change during gestation. According to this criterion, size less than 10 mm is considered normal. Measurements between 10-15 mm are frequently estimated as mild or moderate ventriculomegaly and those larger than 15 mm are described as severe1. The measurement is performed in the transventricular plane at the level of the glomus of the choroid plexus, perpendicular to the ventricular cavity, placing the calipers within the echogenicity generated by the lateral walls2.

The atrium of the lateral ventricle is the portion where the body, posterior horn and temporal horn converge and coincides with the place where the glomus of the choroid plexus rests3. The atrial diameter remains stable between 15 and 40 weeks of gestation, the average diameter of the lateral ventricle varies between 5.4-8.2 mm4 and the 10 mm measurement is 2.5-4 standard deviations above the average5. A measurement of less than 10 mm by ultrasound should be considered normal1. Ventriculomegaly is classified as mild (10-15 mm) or severe (>15 mm) for the purpose of counseling parents6,7, informing them that adverse outcomes and the potential for other abnormalities are greater when the ventricles measure 13-15 mm8.

The prevalence of mild fetal ventriculomegaly is approximately 0.039-0.087%6. Asymmetry of the lateral ventricles is common and there may be a difference between the two ventricles even in normal measurements. This situation is called ventricular asymmetry and refers to a difference greater than 2.4 mm. Although it is not considered a pathological finding, it should be subject to serial monitoring to rule out progression to ventriculomegaly3.

Although mild fetal ventriculomegaly is frequently an incidental and benign finding, it may also be associated with genetic, structural, and neurocognitive disorders, and the findings may range from normal to severe disability8,9.

Ventriculomegaly can be unilateral or bilateral. Unilateral ventriculomegaly is present in 50-60% of cases and the bilateral form occurs in approximately 40-50%8,10. It is also defined as isolated if there are no structural anomalies or genetic abnormalities. However, some cases reported prenatally as isolated, in the postnatal stage there is evidence of abnormalities particularly present in cases of severe ventriculomegaly6. In cases associated with abnormalities, the prognosis is worse, with a high incidence of morbidity in childhood7. Ventriculomegaly is more frequent in male fetuses, with a male/female ratio of 1.74. It has a markedly worse neurological prognosis in female fetuses11,12, although there is no precise information indicating that severity depends on fetal sex8.

Case report

A 20-year-old pregnant woman came to our hospital for pregnancy control. She had no medical history of interest, except for an abortion. The first trimester screening for Down syndrome was low risk.

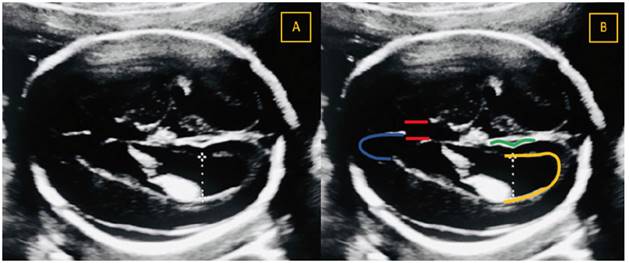

During the anatomical ultrasound at 20 weeks there was evidence of mild dilatation of the left lateral ventricle of 10.8 mm with no other associated anomalies (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Dilatation of the lateral ventricle. Image A shows a transventricular section with measurement of the posterior horn of the lateral ventricle of 10.8 mm. Image B shows the cavum of the septum pellucidum (represented with two red lines), the anterior horn of the lateral ventricle (blue line), the parieto-occipital fissure (green line) and the posterior horn of the lateral ventricle (yellow line). Measurement of the lateral ventricle was performed at the level of the parieto-occipital fissure, perpendicular to the axis of the lateral ventricle and from the internal limit of one margin to the internal limit of the other margin (On-to-On).

The case was referred to a referral hospital where a neurosonographic examination found a normal midline, without anomalies, with interhemispheric sickle of normal morphology. The corpus callosum and thalami were normal (length of the corpus callosum 23 mm, thickness of the corpus callosum 3.2 mm). There was mild borderline ventriculomegaly of unilateral and slightly asymmetric character affecting the whole ventricle, so that the left ventricular atrium measured 10.3 mm and the right ventricle 7.3 mm. The walls of the lateral ventricles were smooth, with anechoic content and the choroid plexuses had normal characteristics. There was no increased echogenicity of the periventricular white matter. The III and IV ventricles were of normal size and morphology. The posterior fossa was normally configured, visualizing both cerebellar hemispheres (cerebellar diameter 20.9 mm) and vermis, cisterna magna of 5.1 mm. There was an adequate degree of maturation of the cerebral cortex for the gestational age (depth of the Sylvian fissure 7.3 mm, of the insula 15.5 mm and of the parietooccipital fissure 4 mm). The neural canal was intact, with no direct or indirect signs of neural tube defect. The rest of the examination had no significant findings. The diagnosis was 20 + 4 weeks gestation with normal developed fetus and diagnosis of mild borderline left unilateral ventriculomegaly slightly asymmetric and without other associated findings.

The parents were informed of the ultrasound findings, diagnosis, and prognosis which, in the absence of other findings, was considered favorable in terms of mortality and neurological development.

To complete the study, maternal infectious serology and genetic amniocentesis were requested and serial neurosonographic controls were recommended, which could suggest complementary tests, such as fetal brain magnetic resonance imaging.

The result of the genetic amniocentesis was 46 XY, fetus of male chromosomal sex with no evident abnormality.

Maternal serology tests revealed immunity for Epstein Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus type I, varicella zoster, rubella, and no immunity for toxoplasmosis.

A new neurosonography was performed at 25 weeks of gestation which showed mild borderline ventriculomegaly, unilateral and slightly asymmetric, affecting the whole ventricle, so that the left ventricular atrium measured 10.1 mm and the right ventricular atrium 7.3 mm.

At 30 weeks of gestation, a new neurosonographic control revealed ventricular system with normal characteristics, without ventricular dilatations (left ventricular atrium 7.6 mm and right ventricular atrium 6 mm).

The parents were informed about the normalization of the findings, so the prognosis was considered favorable in terms of mortality and neurological development, superimposable to those of the general population. It was not considered necessary to perform new neurosonographic controls, and the patient should continue with those established in her center of origin.

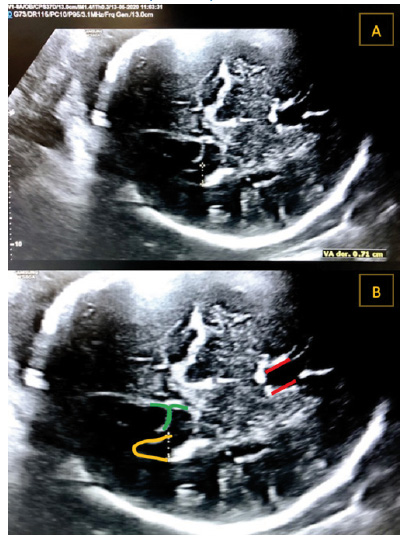

The patient attended our hospital at 32 weeks, and the left lateral ventricle was visualized at 7.1 mm (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Measurement of the lateral ventricle at 32 weeks of gestational age. Image A shows a transventricular section with measurement of the posterior horn of the lateral ventricle of 7.1 mm. In image B, an enlargement of the previous image has been performed and the cavum of the septum pellucidum (two red lines), the posterior horn of the lateral ventricle (yellow line) and the parieto-occipital fissure (green line) have been highlighted.

At 40 weeks, a live male newborn was delivered with vacuum extraction, weight 2,800 g, Apgar 9/10. Physical examination was normal. Transfontanelar ultrasound was requested on the third day of life, which reported central nervous system without alterations in its midline. Corpus callosum without alterations. Ventricular system without dilatation. Choroid plexus of normal size and morphology. Germinal matrix without signs of hemorrhage. There were no areas of periventricular leukomalacia. Posterior fossa of normal morphology. The extra axial space was of normal morphological characteristics. Conclusion: No pathological findings.

He was discharged with a diagnosis of term newborn and small for gestational age. In the follow-up by his pediatrician, he has had a normal psychomotor development for the age of the patient. He is currently two years old.

Discussion

Isolated mild ventriculomegaly is usually a normal variant, given that postnatal evolution and development are usually normal9. The etiology could be related to normal cerebrospinal fluid formation and reabsorption during fetal development. Conversely, mild enlargement of the lateral ventricles may be an initial manifestation of a neurodevelopmental disorder4. Therefore, the detection of mild ventriculomegaly obliges the clinician to rule out the presence of structural anomalies in the central nervous system (CNS) or outside the CNS, genetic anomalies, or congenital infection7,13. Our case was referred to the referral hospital for fetal neurosonography as well as genetic amniocentesis and maternal serology analysis for chromosomal abnormalities and fetal infection, respectively.

Approximately 5% of fetuses with an apparent isolated ventriculomegaly have an abnormal karyotype, frequently trisomy 218,11. Another 10-15% have abnormal microarray findings8. Terry et al. consider isolated ventriculomegaly to be an ultrasound marker of aneuploidy11. The risk of chromosomal abnormalities for fetuses with isolated ventriculomegaly is high when ventriculomegaly is severe, bilateral, occurs in midgestation and does not resolve14.

The incidence of additional CNS and non-CNS abnormalities identified by ultrasound in fetuses with mild ventriculomegaly ranges from 42-84%13 but appears to be less than 50% in most studies4,12. The fetal heart should be carefully examined, and fetal biometry should be evaluated to rule out restricted growth4,8.

Approximately 5% of cases of mild ventriculomegaly are reported as a result of congenital fetal infection, including cytomegalovirus (CMV), toxoplasmosis, and zika virus8. Testing for CMV and toxoplasmosis is recommended when ventriculomegaly is detected, regardless of known exposure or maternal symptomatology8,11.

Fetal MRI can be useful in the evaluation of ventriculomegaly because it can significantly identify anomalies that are not easily detected by ultrasound, or when there is poor ultrasound visualization or if the neurosonographic study is not performed by an expert12. Salomon et al. suggest that MRI can change the management strategy in 6% of cases of isolated mild ventriculomegaly, while Gat et al. note that MRI contributes additional findings in 15.3% of cases6. In the literature, the incidence of significant additional findings detected by MRI in fetuses with mild ventriculomegaly has been 1-14%15. MRI could be of benefit to study the extent of destructive injury in fetuses with known infection, hemorrhage, or ischemia, and when other sonographically evident CNS malformation, such as agenesis of the corpus callosum or Dandy Walker malformation, are present8,15. However, there is no consensus on the clinical utility of MRI. Neurosonography performed by an expert sonographer has a similar certainty as MRI10-12.

Ultrasound follow-up after an initial detection of fetal ventriculomegaly is useful to assess progression, stability, or resolution8,11. Ventricular dilatation progresses in approximately 16% of cases. Conversely, if ventriculomegaly remains stable or resolves, the prognosis generally improves8. And in our patient this was done, with serial fetal neurosonography controls and transfontanelar ultrasound on the third day of life showing resolution of the left ventriculomegaly.

There is no evidence that preterm delivery or cesarean delivery improves maternal or neonatal outcomes in the management of mild ventriculomegaly4. Macrocephaly is rare and it is recommended that the timing and mode of delivery be with standard obstetric indication8,12. Only cases with severe hydrocephalus and head circumference above 400 mm may be candidates for elective cesarean section due to the high risk of obstetric complication4,12. Given the potential that mild or moderate ventriculomegaly may be associated with long-term adverse neurodevelopment, the pediatrician should be alerted to this prenatal finding4,8.

Survival of newborns with isolated mild ventriculomegaly is high, 93-98%. The probability of normal neurodevelopment is greater than 90% and will not be different from that of the general population. Therefore, in the presence of isolated mild ventriculomegaly, after a complete evaluation, the pregnant woman should be informed that the prognosis is favorable, and that the child will probably be considered normal5,8. In our case this is what the parents were informed, given the findings of normality in the genetic study and the negative study of prenatal infections, as well as the resolution of the isolated mild ventriculomegaly.

In summary, when ventriculomegaly is identified, a complete evaluation should include a detailed sonographic study of the fetal anatomy, amniocentesis to evaluate for chromosomal abnormalities, and a study to rule out fetal infection. MRI may identify other abnormalities, although it is unlikely to add additional information beyond that obtained by a detailed neurosonogram performed by an expert in this area. Ultrasound follow-up will assess the progression of ventricular dilatation. In the setting of isolated mild ventriculomegaly, the probability of survival with normal neurodevelopment is greater than 90%.

REFERENCES

1. Pagani G, Thilaganathan B, Prefumo F. Neurodevelopmental outcome in isolated mild fetal ventriculomegaly: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2014;44:254-60. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.13364 [ Links ]

2. Carta S, Kealin Agten A, Belcaro C, Bhide A. Outcome of fetuses with prenatal diagnosis of isolated severe bilateral ventriculomegaly: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2018;52:165-73. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.19038 [ Links ]

3. Leiva JL, Pons A. Rol de la neurosonografía en la evaluación neurológica fetal. Rev Med Clin Condes. 2016;27(4):434-40. Doi.org/10.106./j.rmclc.2016.07.004 [ Links ]

4. Norton ME. Fetal Cerebral Ventriculomegaly. Uptodate (Internet). 2020. (Literatura revisada en marzo 2020, última actualización agosto 2019). [ Links ]

5. Pina S, Costa J, Serra L, Molina C, Escofet C, Corona M. Diagnóstico ecográfico de la ventriculomegalia fetal. Seguimiento posnatal. Prog Obstet Ginecol. 2014;57(5):202-7. Doi.org/10.1016/j.pog.2014.01.007 [ Links ]

6. Thorup E, Jensen LN, Bak GS, Ekelund CK, Greisen G, Jørgensen DS, et al. Neurodevelopmental disorder in children believed to have isolated mild ventriculomegaly prenatally. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2019;54:182-9. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.20111 [ Links ]

7. Bhatia A, Thia E, Yeo S. Obstetric and neonatal outcomes in fetal cerebral ventriculomegaly. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol, 2018;52:165. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.19698 [ Links ]

8. Fox NS, Monteagudo A, Kuller JA, Craigo S, Norton ME. Mild fetal ventriculomegaly: diagnosis, evaluation, and management. SMFM consult series. 2019;45(1):PB2-B9. Doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2018.04.039 [ Links ]

9. Rodriguez RG, Artiñano SC, Delgado RG, Cárdenes IO, Acosta AA, Pérez DH, et al. Fetal isolated ventriculomegaly: prenatal findings and long-term follow up. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2021;58:209-10. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.24420 [ Links ]

10. Ferreira C, Rocha I, Silva J, Sousa AO, Godinho C, Azevedo M, et al. Mild to moderate fetal ventriculomegaly: obstetrics and postnatal outcome. Acta Obstet Ginecol Port. 2014:8(3):246-51. [ Links ]

11. Hernández M, Orribo O, Martínez I, Padilla A, Álvarez M, Troyano J. Detección ecográfica y pronóstico de la ventriculomegalia fetal. Rev Chil Obstet Ginecol. 2012;77(4):249-54. [ Links ]

12. Lipa M, Kosinski P, Wokjcieszak K, Wesolowska-Tomczyk A, Szyjka A, Rozek M, et al. Long - term outcomes of prenatally diagnosed ventriculomegaly - 10 years of Polish tertiary centre experience. Ginekol Pol. 2019;90(3):148-53. Doi:10.5603/GP.2019.0026 [ Links ]

13. Artiñano SC, Rodriguez RG, Delgado RG, García AMC, Cárdenes IO, Pérez DH, et al. Fetal ventriculomegaly: associated conditions in a single centre institution. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2021;58:210-210. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.24421 [ Links ]

14. Zhao D, Cai A, Wang B, Lu X, Meng L. Presence of chromosomal abnormalities in fetuses with isolated ventriculomegaly on prenatal ultrasound in China. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2018;6(6):1015-20. Doi.org/10.1002/mgg3.477 [ Links ]

15. Roa Martínez E, Salazar Arquero F, García Hernández F, Diez Uriel E, Arévalo Galeano N. Ventriculomegalia prenatal: Correlación entre RM y cografía cerebral fetal. EPOSTM SERAM. 2014. Presentación electrónica educativa 1-17. Doi:10.1594/seram2014/S-0411 [ Links ]

Received: October 06, 2022; Accepted: March 16, 2023

text in

text in