Introduction

Over the decades, many different approaches to language learning have been developed and tried with varying degrees of success, reflecting fundamental changes in Linguistics, Pedagogy and technology. The paradigm shift from animal-based behaviourist models of mental functionality to cognitive information processing and representational ones have produced great changes in the way in which language use and learning are conceived. In Linguistics, Structuralism gave way to early formal generative cognitive theories, which subsequently gave way to semantic, functional and pragmatic theories. At about the same time, the Council of Europe presented The Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment (henceforth, CEFR; Council of Europe, 2001). It was intended to be a linguistic-political initiative to promote multiple language use and learning across Europe and a step towards deeper common identity considerations. In Psychology and Education, in a similar fashion, Behaviourism and Instructivism gave way to Cognitivism, where language use and learning were seen as something that could not be explained by conditioning theory but required the participation of internal mental states (attention, memory, reasoning, etc.).

This information processing view of the mind has given rise to the notion of the construction of knowledge or Constructivism, where information is not just added to a person’s mind like water in an empty glass, but gradually built into what was previously there. From Cognitive Constructivism, Social Constructivism has emerged, emphasizing the communicative (socially mediated) way in which language is used and learnt. The emphasis in learning is now placed on learner-centred approaches, discovery, problem solving, and collaboration, where developing competences are seen to be more effective than passively assimilating knowledge.

In the field of educational technology, open education resources and practices, which are always in a state of flux and exploratory application, evolved into courses, namely Massive Open Online Courses (or MOOCs, Siemens, 2012; Read & Barcena; 2014) that could be used for language learning, (Language MOOCs or LMOOCs; Martín-Monje & Barcena, 2014; Read, 2014). These courses represent an effective mechanism for language learning for a wide range of social groups, not just central Europeans and north Americans, but also other people from other cultures, such as those from the MENA (Middle East or North African) region. They are also very appropriate for marginalised groups such as migrants and refugees if appropriate adaptations are made (Read, Sedano & Barcena, 2018). As well as the appearance of LMOOCs, another significant change in the way that languages can be learnt comes from the prevalence of mobile devices (over 40% of people on the planet have smartphones, and more than 65% some kind of mobile device) and the affordances for learning they have. These devices represent an effective and easy to hand course client that enable students to work and study in a flexible way, wherever they are, if the courses are developed with them in mind (Read & Barcena, 2015). Mobile devices also represent a language learning device in and of themselves (a discipline referred to as Mobile Assisted Language Learning, or MALL; Kukulska-Hulme & Shield, 2008), and also form part of a changing panorama for learning and engagement (Traxler, Read & Barcena, 2018).

Even given these advances in the area of language teaching and learning, it is argued in this article that there is still a need for a standard teaching-learning framework for languages, that can underlie the activities and exercises included in LMOOCs and MALL apps. Such a framework would replace the ad-hoc approaches used in the majority of these learning scenarios and thereby solve the problems and difficulties present when trying to learn a language online or via an app, namely:

The oversimplification and reduction of the vastness and complexity of the learning domain to a few formal linguistic aspects, whose learning is presented in a vacuum, ignoring the advantages of enhancing cognitive processes, linguistic interrelations, and the overall functional, communicative context in which they take place (e.g., Suri & McCoy, 1993; Holland et al., 1995; Dicheva & Dimitrova, 1998).

The development of language learning content and systems which do not consistently follow any theory about the way people learn second languages (e.g., Oxford, 1995; Garret, 1995; Salaberry, 1996).

Outline of a framework for online second language teaching/learning

The outline of the framework that is presented in this article would need to represent the second language knowledge in a systematic and extensive fashion. When considering how to do this, it can be acknowledged that the CEFR is still the most acknowledged official reference for language didactics. It is the culmination of work on language policy that has been undertaken by the Council of Europe since its very beginning and has profoundly influenced the learning and use of languages in European countries (Trim, 2007). It attempts to provide a common basis for enabling the description, teaching and assessment of language courses and learners across Europe, in order to “make it easier for teachers, learners and testers to communicate across languages, educational sectors and national boundaries”1. The CEFR was founded upon the belief that language education cannot be separated from social policy, and reflects a general aim of promoting:

Plurilingualism: people should develop a degree of communicative competence in a range of languages throughout their lives following their needs.

Linguistic diversity: Europe is multilingual, and all its languages are equally valuable.

Mutual understanding: intercultural communication and the acceptance of cultural differences is strengthened by learning other languages.

Democratic citizenship: the plurilingual competence of individuals facilitates their participation in multilingual social processes.

Social cohesion: access to language learning is essential for promoting equality of opportunity for personal development, education, employment, mobility, access to information and cultural enrichment depends.

The CEFR is of particular interest to course designers, textbook writers, testers, teachers and teacher trainers (in fact, to anyone who is directly involved in language teaching and testing), as it facilitates a clear definition of teaching and learning objectives and methods and provides the necessary tools for assessment of proficiency. It contains a number of descriptor scales which describe the competences needed by language learners to become proficient users of another language, and they are all duly justified from a functional, communicative perspective. The CEFR describes in a comprehensive manner: the competences necessary for communication, the related knowledge and skills, and the situations and domains of communication. Behind this document is the widespread functional and communicative approach to human language. It follows an action-oriented approach, which takes into account the cognitive, volitional and emotional resources as well as the abilities specific to an individual as a social agent.

The framework characterised here is intended to be applied in any LMOOC or MALL app. To illustrate some of its characteristics, an example of a Professional English LMOOC (https://iedra.uned.es/courses/course- v1:UNED+InfProf_02+2018/about) has been used. A first edition of this LMOOC was produced by the authors in 2013, and was the first one in Europe. It was launched on the OpenUNED platform (OpenEdX) and is still available today.

Pedagogic aspects of the framework

Following an analysis of the theories that have attempted to explain the way in which second languages are learnt, the most comprehensive and insightful paradigm for this purpose is argued to be Constructivism. The more established paradigm of Instructivism has been widely criticized for its poor results, reflecting its lack of connection with the underlying mental mechanisms responsible for language learning and use. It perceived teaching as a mere information transmission process consisting of direct, explicit instruction by a (knowledgeable) teacher, who employed objectives and lesson plans related to an overall curriculum guide in order to teach specific content. On the contrary, Constructivism is based on the idea that a learner builds knowledge and skills dynamically, and information is contained within these “built constructs”. Constructivist proposals are generally seen to be clearly superior in that they attempt to present learning materials in a fashion that is closely tuned to how the learner’s internal cognitive processes actually take place, favouring comprehension and meaningful assimilation. Constructivism is in essence cognitive, interactive, and integrative; it focuses not only on what is learnt, but also on how it is learnt, taking into consideration what knowledge the learner brings to the learning process and how he incorporates the new knowledge into his existing mental structures. There are many different views within Constructivism, but it is commonly agreed that it is the individual’s processing of the environment and the resulting cognitive structures that produce learning, rather than the environment itself. At the same time, the student builds a set of internal resources that are helping him to learn “how to learn”, and hence this awareness of himself as a learning agent empowers him for life-long knowledge consolidation and expansion.

The research presented here aimed at reconciling the debate on the individual versus social nature of human cognition which, as has been argued here, need not be the case. The two main forms of Constructivism are Cognitive Constructivism and Social Constructivism. In the former, adult learning is viewed as the incorporation of new knowledge into existing mental schemata via experience. As learning takes places, the schemata are changed, updated, enlarged, and made more sophisticated. This provides an ideal basis for effective learning because the mind looks for whatever related knowledge, experience, etc. is stored in order to build in further (second language) knowledge connections. Social Constructivism emphasizes (more than its cognitive equivalent) the fundamental importance of culture and environment in knowledge construction. Learning strategies based upon Social Constructivism use activities that are meaningful to the students, including negotiation, discussion, and collaboration, and value them over correct answers. It has been argued that language learning in particular is essentially practical and skill-based in the different spheres of reality. Its main goal is to undertake activities with other speakers using the target language according to the communicative situation, and a fined grained combination of both constructivist paradigms is the most comprehensive and insightful way of capturing how this domain is actually learnt by adults.

The framework designed here is constructivist in the following ways: it is learner-centred (he is involved in the learning process, has a certain degree of control and decision, is permanently informed of his learning state, etc.), action oriented (all learning revolves around the undertaking of activities which mobilize high-order cognitive processes, such as reasoning, supporting, contrasting, justifying, etc., some of which are collaborative to reflect the social nature of language interaction), uses authentic learning (the texts in the units of the Professional English course mentioned above follow a realistic threaded story with a set of constant characters, the activities focus upon aspects of realistic communicative situations, etc.), follows the spiral approach (topics are reviewed “in a spiral fashion”, where the same topic is revisited now and again with an increasing level of complexity), has an attentional learning/non-attentional application mechanism (the former takes place when a student undertakes an activity mechanically, focussing his attention on what he is doing, and the latter, when he is practicing language aspects with no overt awareness [in multi-topic activities]), contains a scaffolding mechanism (support is provided to the student when difficulties are detected, and gradually removed as evidence of comprehension appears), and uses peer monitoring (students review and evaluate the work of less advanced colleagues, which is considered to be mutually beneficial).

The framework is argued to provide a fine-grained combination of individual (cognitive constructivist) and collaborative (social constructivist) learning. Initially, individual learning is undertaken through the performance of simple activities on a given notion (in a “notional-functional syllabus” sense). Once there is evidence that prototypical conceptual learning starts to take place, collaboration becomes possible (for the same notion or concept) through the performance of more complex activities (typically involving several associated tasks). For collaboration to occur, the students working together must be capable of reaching mutual understanding. Such understanding requires communication in the second language between the activity participants which, in turn, requires communicative strategies to be adopted (with the intervention of personal skills and existential competence). The application of these strategies therefore permits collaboration to take place, reinforce previous individual learning, and trigger further individual study.

Historically, whilst constructivist inspired approaches to learning have been used for centuries, none have tried to reconcile and integrate the cognitive constructivist and the social constructivist paradigms. It has been noted here that there is some incipient experimental teaching work which shows that combining individual learning activities with collaborative group-based ones is an effective way to enhance learning. However, up until now, such a combination has been reduced to brief peer intervention in a conventional instructivist classroom and testing how collaborative learning fosters the development of critical thinking (and learning) through discussion, clarification of ideas, and evaluation of others’ work. The framework should define the most effective underlying pedagogic paradigm to be hybrid, i.e., made up of the balanced and integrated combination of Cognitive Constructivism and Social Constructivism, to reflect the double individual and social dimensions of human beings.

Linguistic aspects of the framework

From the over 250 pages of taxonomic discussion and analysis of language use and learning that makes up the CEFR, a set of eight key concepts have been extracted that are fundamental for the definition of the framework being proposed here: language proficiency levels, communicative language competence, competence descriptors, language activities, communicative language processes, external context of language use (domains/spheres of reality and situations), texts.

Language proficiency levels. The CEFR defines six language proficiency levels that capture the general language competences that students obtain as they progress in their language learning: A1 - Breakthrough; A2 - Waystage (A2+ - Strong Waystage); B1- Threshold (B1+ - Strong Threshold); B2 - Vantage (B2+ - Strong Vantage); C1 - Effective Operational Proficiency; C2 - Mastery.

Communicative language competence. The most fundamental distinction made in the CEFR is between communicative language competences 2 and activities. The former is the set of the learning resources (knowledge, skills, etc.), and the latter are what the learner can do with them. Three types of competences are distinguished in the CEFR: linguistic, sociolinguistic, and pragmatic3. The first of them relates to language as an organizational system (e.g., lexical, phonological, and syntactic knowledge and skills). The second refers to the sociocultural conditions of language use (rules of politeness, linguistic codification of rituals, etc.). The third and final is concerned with the functional use of linguistic resources (language functions, speech acts, etc.). Due to the great degree of overlap between sociolinguistic and pragmatic issues (see Martínez Dueñas, 2005)4, it is argued that they should appear combined in the framework.

It is argued here that any didactic materials used in an LMOOC or MALL app should be divided into units corresponding to one or more major notions. The content is modular and divided into grammar (including inflexional morphology and sentential syntax), semantics (vocabulary/terminology, idiomatic language [very common in specialized domains], metaphor and metonymy, etc.), and discourse (including language functions, pragmatic features, text markers, etc.)5. This is a simplification of the CEFR, which contemplates the lexicon, grammar, semantics, phonology, orthography and orthoepics within the realm of the linguistic competence. In the framework, language functions should link the general notions to the authentic acts that can be accomplished using language (they include greetings, explanations, contradictions, judgments, illustrations, comparisons, etc.), and are therefore studied at the discourse level. Sociolinguistic competence is acquired through the creation of cultural contrasts as the story develops.

Competence descriptors. One of the key CEFR concepts proposed for the framework is that of can- dos, i.e., the language competence descriptors at a given common reference level (A1, A2, etc.). In the Professional English LMOOC, there are can-dos corresponding to all the language proficiency levels covered in the course. These have one major similarity with those of the CEFR and three differences. The similarity is that they enable functional and communicative learning. The differences are the following:

They are far more specific and adapted to the field of (international) professional English and include a reference to the discourse/text type appended in brackets (this information may be useful for future versions of the course or analyses of its domain).

The can-dos are linked to the texts in the course units. There are between one and three can- dos associated with each text, which express the specific competence of the learner when he finishes working with the activities attached to the text. This linkage permits the retrieval of adequate materials for the development of the particular competence captured in the can-do.

They are linked to contextualized language activities and communicative language processes in order to enable functionally motivated student diagnosis to be undertaken.

Contextualized language activities. According to the CEFR, it is the performance of activities that enable the learner’s communicative language competence to develop. The term prototypical activity is therefore recommended for the framework to refer generically to activities according to the direction of communication: reception, production, interaction and mediation. The first three are also considered to play a major role in language learning in constructivist terms, so mediation (basically translating and interpretation) can be left out (and the most interesting aspects from the learning perspective, such as summaries, paraphrases and other reformulations, should be incorporated as part of any interactive activities). When a prototypical activity is seen in the context of one of the four spheres of reality that are distinguished, it is referred to as a contextualized language activity.

Communicative language processes. They are defined in the CEFR to be the chain of neuropsychological and (and physiological) events involved in the reception and production of speech and writing. For the sake of computational modelling, these processes have been reduced to what is typically used in the literature as the “four basic linguistic skills”: reading, writing, listening, and speaking. While the communicative language activities should be contextualized in the framework according to the spheres of reality, these processes entail modality, i.e., their oral/written input/output nature.

Domains/spheres of reality. The external context of language use6 in the CEFR can be seen to be divided into domains and situations. Therefore, the first premise when designing the framework was that each course unit would provide varied scenarios for working on the different spheres of reality of a given speaker (or spheres of action, to use the CEFR’s terminology) and situations. Spheres of reality are also referred to in the CEFR as domains, and defined as the broad sectors of life in which social agents operate. Four domains are distinguished: educational, occupational, public and personal. In this framework, however, the term domain should be substituted by spheres of reality because it is polysemic here since it has rather different meanings in sublanguage theory and others. In the example Professional English LMOOC, four spheres of reality were identified: private (the sphere of intimate relationships), personal (the sphere of personal acquaintances), public (the sphere of general social relationships with other citizens), and occupational (the sphere of relationships in specialized working environments).

The major difference with the CEFR is that the educational domain is included primarily within the occupational sphere (since professionals mainly follow in-company training and there is a specialized, formal use of terms and structures or any of the other spheres for more informal courses [hobbies, etc.]). Furthermore, a distinction is made within the personal sphere, distinguishing the private and the personal sphere (for the informal, affectionate language used within the nuclear family and other closed relationships, and the less colloquial language used with personal acquaintances). Each sphere of reality has a major impact on the type of language used in the corresponding communication acts at all linguistic levels. Each language proficiency level is related to each of the four spheres of reality. This distribution of units within the different spheres of reality reflects the relevance given to them in the field of professional English. Thus, slightly more than one third of the syllabus deals with specialized communication at work, another third deals with general social communication, and the final third deals with personal and private communication.

Situations. The notions covered in the units are also distributed across various situations, locations and text types, which constitute the external context of use of the language together with the spheres of reality. The CEFR distinguishes situations and, within these, locations, institutions, persons, objects, events, operations and texts. In order to simplify such descriptive parameters, the three categories with most impact on professional English were selected, namely locations (with attention to the type of related leisure/work activities), social roles (persons, with attention to mutual personal and/or work relationships) and text-types (texts). The last one is of particular relevance in languages for specific purposes since, it is a well-known principle of genre theory that languages always adapt to the communicative purpose or intent, and the types of text where they are used. Furthermore, in closed, specialized communicative contexts, language makes use of distinct, specialized forms to facilitate communication. Thus, in order to cover the main forms and functions that can be encountered in the professional field, a classification of all these elements was undertaken for the Professional English LMOOC. An example of the external context parameters is presented in table 1.

Table 1 An example of Promoting business expansion: the real estate from unit 7

| EXTERNAL CONTEXT | TEXT 1 | TEXT 2 | TEXT 3 | TEXT 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Locations | At a trade fair | -- | -- | -- |

| Social roles | Corporation / Potential Customer | Corporation / Potential customer | Employee / Potential customer | Customer information department / potential customer |

| Discourse / Text types | Poster (written) | Radio commercial (oral) | Phone conversation (oral) | Fax (written) |

Other examples of locations here are: the protagonist’s office, other offices in IBS (International Business Services, a fictitious company invented to contextualize the learning materials) and other facilities at the company premises (e.g., the meeting room, the projection room, etc.), private homes, restaurants, bars, real estate agencies, shops, stations, etc. Other “persons” include kinships, friends, landlords, classmates, colleagues, managers, subordinates, customers, clients, cleaners, lawyers, TV presenters, etc. Finally, text-types include business letters, CVs, report memorandums, instructional manuals, contracts, brochures, newspapers, email, etc.

Texts. As can be seen in table 2, each unit in the Professional English MOOC consists of four texts, which the CEFR (p. 10) defines as:

“Any sequence or discourse (spoken and/or written) related to a specific domain and which in the course of carrying out a task becomes the occasion of a language activity, whether as a support or as a goal, as product or process”.

Table 2 A sample of unit content showing the relation of notions to texts

| NOTIONS | TEXT 1 | TEXT 2 | TEXT 3 | TEXT 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unit 1 → Employment offers and demands | Job advertising | Job interview | Job application forms | Resumes |

| Unit 2 → Starting a new job post | Job acceptance letter | Office plan | Getting acquainted with your colleagues | Taking notes on your agenda |

In the framework texts should have this purpose as well, i.e., they provide samples of a particular type of notion and they embody vocabulary, grammatical forms and functions that are to be studied in relation to such a notion. It was considered that notions are such broad concepts that at least four texts were required to illustrate them. Furthermore, language contents are organized in topics7, and linked to the texts (there are between three to six topics for every text). It is essential to note that texts in the “CEFR sense” can in fact be written texts (e.g., e-mail, chats), audio sequences (e.g., radio recordings, phone conversations), video fragments (e.g., scenes both within and outside of the company) and images (e.g., plans, photographs).

In accordance to the adopted constructivist paradigm, which promotes the use of authentic learning prompts, the texts that make up the units of the Professional English LMOOC form part of a unique story: that of an American holding company named IBS, which has a small set of constant characters (who work, have a social life, travel, are promoted, etc.) and other changing ones (rivals, punctual collaborators and externally contracted employees, potential customers, etc.). The sequence of units has been carefully designed to be modular, so that in the future the course’s didactic contents can be expanded without affecting the coherence of the thread of the story.

It was noted above that competence training was organised into three linguistic levels: grammar, semantics, and discourse. Each level corresponds to a sequence of related topics. All of these topics (but particularly the ones that deal with the more organizational aspects of language) are selected on a double basis; firstly, their relevance to the notions they are related to, and secondly, their gradual complexity. Following the principles of the notional-functional syllabus, the learning approach of the framework is not strictly graded according to structure, thus resembling to some extent the ideal linguistic immersion scenario, where the learner is exposed to heterogeneous communicative situations from the start. However, the limitations of time and diversity of target language input, etc., in any other learning scenarios make it necessary to impose some structure in the syllabus.

Each topic is made up of well-illustrated theoretical explanations (in English and with minimal linguistic terminology) and practical activities of an individual and a collaborative nature (for the respective modules). Following the CEFR’s activity-based approach (p.10):

“language activities involve the exercise of the learner’s communicative language competence in a specific domain in processing (receptively and/or productively) one or more texts in order to carry out a task”.

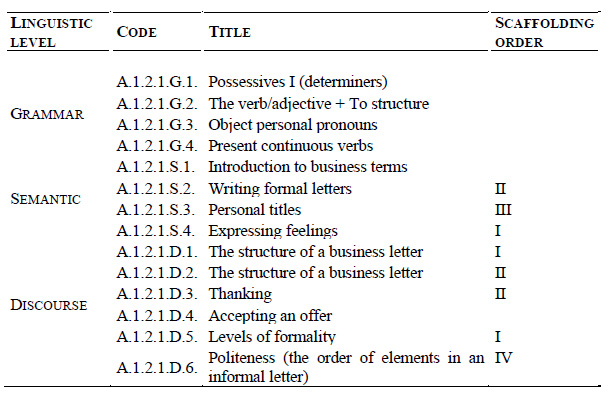

An example of the topics that correspond to the first text of the second unit in the Professional English LMOOC can be seen in table 3. It should be noted that sometimes there is an overlap between the contents of the three levels, particularly in the case of discourse topics (which reflects the nature of linguistic levels and is not considered to be important).

The learner is encouraged to perform, firstly, individual activities and, then, collaborative ones for reinforcement and consolidation (an aspect of the framework of clear constructivist origins). Collaborative activities are richer and typically consist of several tasks, due to the fact that they are not automatically corrected. Both types of activities are used for continuous individual student progress.

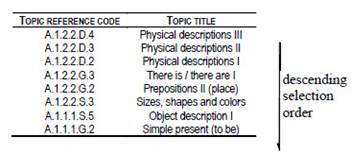

An extended spiral approach with a scaffolding mechanism and an attentional learning vs. non- attentional application. In order to prevent “knowledge holes” that may eventually lead to a “structural collapse” of the learning process, the spiral approach has been incorporated into the framework. Hence, rather than following a structural syllabus with topics tightly organised in sequences, the language difficulty is only partially graded, and topics are reviewed “in a spiral fashion”, where the same topic is revisited now and again with an increasing level of complexity (Martin, 1978). The purpose of the Roman ordinal numbers appended to the topic titles (seen in both the fourth column of table 3 and the second of table 4) is to enable the identification of directly linked topics and the second step of scaffolding (see below).

Scaffolding is a didactic mechanism which provides support to the student when difficulties are detected by adding “supportive devices”, and gradually removes it as evidence of comprehension appears, a clear metaphor of the way in which buildings are actually scaffolded as they are built (McLoughlin and Marshall, 2000; Barcena and Read, 2004). In the framework it is defined to work as follows:

It causes the student to be presented with supplementary activities (based upon the same theory) and, in the case of “minimum theory” learning8, further theoretical explanations can be accessed by him.

If mistakes persist, then the framework should offer simpler (from the same or previous units) theoretical explanations and activities on the same topic (e.g., plural morphemes, which in the LMOOC’s syllabus is tackled in three topics, respectively A.1.1.1.G.4 Plurality I and A.1.4.1.G.2 Plurality II).

Should the student still have problems, he will be presented with a simpler yet related topic (e.g., for A.2.7.1.G.3 Either/Neither, not, nor; A.1.4.2.G.3 The expression of negation II; and A.1.3.3.G.4.

The expression of negation I). “Learning routes” are available that represent the teaching path that an experienced English teacher would take (an example is provided in table 4).

In this example, if the student makes significant mistakes while undertaking activities related to physical description, it will select a further activity from table 4, in descending order. In order to provide more accurate scaffolding, two general restrictions have been argued to be necessary for the selection: firstly, formal and semantic errors cannot be scaffolded with grammatical topics, and secondly, morphological and syntactic errors cannot be scaffolded with semantic topics.

Conclusions

The work presented here has described a proposal for a theoretical framework for language teaching and learning that can be used for the elaboration of online courses such as LMOOCs and syllabi and didactic materials for MALL apps, regardless of the number of students. This framework has been refined during the process of designing and developing a Professional English LMOOC. Within this continuum, the more specialized the sphere of reality, the better defined the lexical items and the syntactic structures, and the more deviations there are with respect to standard language. It should be emphasized that the word “professional” refers to the general needs of a person who’s private and working life revolves around modern communicative situations (e.g., socialising, travelling, online shopping, international banking, etc.) in English. As can be appreciated, there is an intrinsic learner centeredness in the teaching of professional English (although, in practice, not as much as in standard ESP). This variant can be seen to contrast with sublanguages (Barcena and Read, 2000), such as, e.g., business English, legal English, and technical English. These well delimited domains focus on a particular professional/academic field of specialization, where knowledge of one is of little use for another.

It has also been argued that the CEFR offers a way to structure the knowledge and skills required in second language learning in a way which is coherent with the constructivist paradigm, following widely accepted European recommendations. It has been adopted because it provides a notional-functional classification of language use and learning (“elegantly” capturing the vastness and complexity of languages and their functional nature), and it is the first general attempt to produce a taxonomy of the elements that intervene in language use and learning, enabling comparable syllabi to be created for all European languages. As such, it appeared to be the most appropriate way to structure the knowledge and skills in a language learning course without recurring to ad hoc methodological solutions.

While total theoretical coherence is maintained with the functional and activity-based aspects of the CEFR, several methodological departures have been made for the framework, which have been presented: Eight key concepts that are fundamental for the definition of the framework: language proficiency levels (Breakthrough, Waystage, Threshold, Vantage, Effective Operational Proficiency, and Mastery; as per the CEFR), communicative language competence (two types are distinguished: linguistic and pragmatic, the latter of which includes sociolinguistic features), competence descriptors (specific can-dos, which describe what language users can normally do at different stages of their learning process), contextualized language activities (the prototypical activities of the CEFR are embedded in one of four domains/spheres of reality), communicative language processes (which have been reduced to reading, writing, listening, and speaking), external context of language use (spheres of reality [referred to as domains in the CEFR] and situations, within which locations, social roles and text/discourse types are distinguished to quantify the notions and functions in the domain), and texts (sample sequences [written, oral, visual, etc.] related to a given notion).

Finally, the authors believe that the framework presented here could provide the structure and coherence needed for effective LMOOCs and MALL apps to be developed in a systematic way that facilitates online second language learning.