Introduction

Good faith in Russian law: objective and subjective.

In Russian civil law, the term "good faith" ("good conscience") historically refers to two different concepts, in connection with which it is traditionally accepted to distinguish between objective and subjective good faith (Agarkov, 1946; Novitsky, 1916). Objective good faith (honesty) is an "external measure of behavior," and "means nothing more than hones honesty in human relationships". Subjective good faith is "a certain consciousness of a person, ignorance of some circumstances, with which the law considers it possible to link certain legal consequences", or even "ignorance of the circumstances preventing the person from acquiring a particular right»1.

The approximate correspondence of legal terms: "objective good faith" in Russian is honesty in English, Treu und Glauben in German; "Subjective good faith" in Russian is bona fide in Latin, good faith in English and guter Glaube in German (Paturet, 2019).

Good faith in an objective sense (honesty) is applicable in relative, primarily in contractual relations. In business relations, the general civil category of objective good faith is clarified and sounds like "fair customs in industrial and commercial affairs"2, "fair business practice"3, "compliance with professional ethics"4, often clothed in a very specific form, conventionally denoted as soft law, expressed in the form of codes of good business practices, codes of conduct5. Public-legal interpretation of objective good faith in private law is the requirement of "fair competition", which led to the application of objective good faith in the field of intellectual rights (especially in respect of trademarks, where the category of "unfair competition" has a serious position6). Obviously, objective good faith is not a matter of fact, and not even an assessment of a fact, but a legal qualification.

Subjective good faith is guessed in the text of Russian regulatory acts on markers "knew / did not know", "should have known / should not have known", "could have known / could not know" (Fallon, 2017). The establishment of subjective good faith is a matter of establishing the fact of the court (knew / did not know). One gets the impression that subjective good faith is an applied category, completely lost in the brilliance of objective good faith. This impression is erroneous.

The purpose of subjective good faith in the legal relations of various natures is not as obvious as the purpose of objective good faith. This suggests that subjective good faith is a more subtle and complex category than objective good faith.

Subjective good faith is not a kind of universal, uniform concept, the essence of subjective good faith is changeable depending on the tasks that are set by law and order (Berg, 2014). It is necessary to allocate at least three functions of subjective good faith in various areas:

The generation by subjective good faith of legal consequences that, without consideration of good faith, should not have occurred - the transformation of the unlawful state into a legitimate one (for example: the conscientious acquisition of seniority7).

Preservation due to the subjective good faith of the ensuing legal consequences (example: a disputable transaction with respect to a bona fide counterparty remains in force, it cannot be considered invalid).

Use of subjective dishonesty instead of civil guilt in the application of protection measures - but not responsibility measures! (Example: an unscrupulous owner, who is in possession of property, is responsible to the owner more than the bona fide owner would answer).

Results

Formulation of the problem

Objective good faith (honesty) only since 2013 received a formal consolidation in Art. 1 Civil Code of the Russian Federation (hereinafter - the Civil Code, CC RF)8 as the main principle of civil law (principle of civil law).

The euphoria from the legalization of the principle of good faith seems to have declined. Largely empty discussions9 about the justification of introducing the principle into law have subsided, in the doctrine and law enforcement a meaningful subject-matter perspective of the research prevailed, in a sense, forgotten legal categories10. It should be assumed that the most important is the question of the peculiarities of applying the designated principle in the context of various types of civil legal relations (Martinez & Jose, 2018) (absolute / relative, property / obligation, etc.), legal regimes (property, obligation, corporate, inheritance, family, etc.). In any case, it seems doubtful that the requirement of the faithful exercise of rights and performance of duties is a unitary category with a single content, applicable in such content to all phenomena in private law without exception.

The authors are aware that the category of subjective good faith has a fairly widespread use in the private legal sphere (Golubtsov, 2016), is an element of the general provisions on the establishment of civil rights (clause 6 of article 8.1 of the Civil Code of the Russian Federation), the rights of legal entities (clause 2 of article. 51, Sub. 3, Section 2, Article 60.2 of the Civil Code of the Russian Federation), legal regime of transactions (Articles 173, 174, 174.1 of the Civil Code of the Russian Federation), contractual law (Section 3, Article 388 of the Civil Code of the Russian Federation), corporate law parts close to obligations (paragraph 3 of clause 6 of article 67.2. of the Civil Code of the Russian Federation) or transactions (subclause 2 of clause 6.1. 79 of the Federal Law No. 208 dated December 26, 1995 "On Joint-Stock Companies") physical rights persons (paragraph 4 p. 1 of article 28 of the Family Code of the Russian Federation). Taking into account subjective good faith, the legal consequences of the representative’s actions during the termination of authority are determined (clause 2 of article 189 of the Civil Code of the Russian Federation), as well as in the case of securities (clause 2 of article 358.17 of the Civil Code of the Russian Federation). Moreover, the legislator considers subjective good faith as a significant circumstance that he is ready to refute the public law prescriptions depending on the qualification of the behavior of the participant of civil turnover: in 2018, the concept of unauthorized construction (Art. 222 of the Civil Code of the Russian Federation) included a subjective criterion - unauthorized construction is carried out by an unscrupulous person (he knew or could know about the existing restrictions on the use of the land).

Naturally, these examples do not claim to be exhaustive. In principle, if you aim to form a complete list of such cases, it will be extremely extensive. Even a superficial glance can lead to the impression that the legislator, like a sower, haphazardly "scatters" instances of applying subjective good faith in the texts of regulatory acts, without particularly going into details and the consequences of using such a tool. At the same time, it seems that such a judgment is rather incorrect. It should be assumed that each case of application (use) or refusal to take into account subjective good faith is a conscious choice. At the same time, there is no doubt that in various sub-branches of a private-law nature subjective good faith has various grounds for application, is used to achieve generally comparable, but different goals and results. It can only be noted in advance that the rules on subjective good faith operate mechanically in the same way: on the basis of such good faith, the rule of law declares for those persons who acted flawlessly, have fulfilled a certain standard of conduct that has occurred such consequences that, from the point of view of the law, due to the lack of the necessary legal composition, should not occur, and all third parties are bound by such consequences (Tepedino, 2016).

Taking into account the extreme breadth of the possible subject of the study, it is advisable to limit the subject of the study to the definition of the grounds, limits and consequences of the use of the construction of subjective good faith as an element of the legal regime of objects of civil rights, the structural formation of private law, which regulates the methods of attribution, attribution of tangible and intangible benefits to participants in civil turnover. The findings of the analysis can be verified for the possibility of applying them in the sphere of turnover of property intellectual property rights.

The purpose of this study is to designate the problem that will soon overtake the Russian legal order and possible ways to solve it: the admissibility of applying the category of subjective good faith to relations arising in connection with the establishment and acquisition of intellectual property rights. The only reason why this issue does not excite the minds of scientists and does not create visible, massive problems for civil turnover is the underdevelopment of the impact of this very turnover of property rights on the results of intellectual activity; there seems to be no other reasons. The authors believe that the Russian legal order has a unique chance to once again outstrip the so-called "developed legal orders", to become the first in the field of intellectual rights, meaningfully setting the regulatory basis for taking into account subjective integrity in the so-called intellectual property. In turn, the doctrine of private law has the opportunity to fulfill its real purpose: to give the legislator, law enforcement officer, trafficking, proper ideas for the formation of a legal regime, assess the actual circumstances of disputes, organize relations about one of the most important objects for civil circulation, but not pathologist function already accustomed11, who, as we know, is never wrong and perfectly reveals the causes of negative phenomena, but is absolutely unable to prevent them.

Accordingly, the subject of further discussion is the definition, substantiation of the substantive characteristics of the concept of subjective good faith as an instrument of private law, which has a general purpose for a whole group of institutions.

Subjective good faith as a legal structure of civil law.

It is generally recognized that objective good faith is the principle of modern civil law (and in this respect it is not so important whether such good faith is enshrined in positive legislation).

Subjective good faith in the first approximation is a tool, the monopoly on the application of which belongs to the court, and the very possibility of application is determined by the arbitrariness of the legislator, which in general should be considered justified by a methodological method based, among other things, on the principle of legal certainty. On the one hand, a participant in a turnover who acted in good faith and prudently has the right to claim the emergence of a certain legal status, which is a common consequence of the accumulation of a certain legal composition. On the other hand, other participants build their own methodology for exercising civil rights and fulfilling their duties, taking into account or, on the contrary, excluding the possibility of invasion of their property sphere by persons with whom they are not connected with any relative relationship. In the context of the legal regimes of objects of civil rights, consideration of subjective good faith is a special element of such a regime, declaring the subject of the right to such an object the possibility of losing the right to it without any equivalent compensation from the acquirer of such right or to the refusal of benefits associated with rightholder12. In turn, third parties, when they enter into a relationship with respect to such an object of civil rights, have a deliberate expectation of the possibility of lawful appropriation of such an object of civil rights or the absence of other negative consequences due to interaction with a person who is not authorized to commit transactions with such an object for one reason or another.

In its essence, the establishment of a right in the absence of a proper reason, the refusal to an authorized person to receive benefits from the exploitation of its position as the right holder is an intrusion into the property sphere of the right holder who does not participate in the relative relationship that arises without his participation, and which is forced by law and order to humbly accept the consequences of having such an outside transaction for him, the consequences of which are determined by taking into account subjective good faith. The rightholder cannot or does not have the ability to influence the content of the transaction; it takes place in addition to his will. In any case, the rightholder has no idea about the essence of the circumstances. Consideration of subjective good faith entails a plot in which the legal facts in normal conditions of the regulatory model of regulation of the relevant relations generate some effects that are beneficial for the right holder, are declared not generating such consequences. The rightholder loses the legal status on which he was entitled to count. Such a "defeat of rights" is carried out in circumstances in which the right holder does not participate, he is a third party with respect to the facts to be established. Moreover, an assessment of the use of subjective good faith in such a context makes it possible to make a judgment that the use of such an instrument of influence on economic relations can significantly affect the interests of third parties in the traditional sense of this term. For example, the debtor’s creditors are deprived of the opportunity to receive satisfaction at the expense of some property, the return of which to the debtor is denied, with reference to the good conscience of the acquirer. It is obvious that the possibility of establishing the rights to the relevant object, contrary to the law, the refusal to extract benefits from the position of the rightholder, the possibility of influencing the interests of third parties outwardly represents a technique of legislative technique that can be defined as a restriction of civil rights and fully falls within the scope of the principle of inadmissibility, as a general rule, such a restriction (paragraph 2 of item 2 of article 2 of the Civil Code of the Russian Federation). Such a judgment allows us to conclude that subjective good faith as a tool for determining the content of relations included in the subject of civil law regulation is not presumptively included in the legal regime of an object of civil rights until consciously authorized by the legislator. Otherwise, the establishment of such a method of strengthening the rights of participants in civil turnover is based on the arbitrariness of the legislator, who, guided by certain motives, makes a sensible decision on the introduction or refusal to introduce such an element of the legal regime.

The judgment that the use of subjective good faith as a tool to strengthen the rights of participants in civil turnover against the will of the actual holder of rights is a legislative establishment, is confirmed by a retrospective analysis of the appearance of such rules in the Russian legal order.

Subjective good faith in various absolute legal relationships

Rights to non-documentary securities

At one time, Russian judicial practice came to the need to use a model of vindication claim to protect the rights of holders of non-documentary securities, which were illegally written off from the owner’s account. This step was accompanied by reservations: "The vindication claim is elected by arbitration courts as a means of protection in case of unlawful alienation of shares, probably, it is an exit chosen by the courts not from a good life. In part because the doctrine in the present circumstances cannot offer a claim that would satisfy the needs of practice»13; «the use by courts of property-legal means of protecting the rights of holders of non-documentary securities can hardly be justified by the fact that the courts equate the thing with non-documentary securities. Rather, this is because the positive law, and the theory has not developed special means of protecting the rights of holders of such securities»14. It was believed that until 2013 the text of Art. 128 of the Civil Code of the Russian Federation allowed all kinds of securities (including non-documentary) to be assigned to things, which served as a formal justification for the analogy on the use of vindication to non-documentary securities.

The application of the vindication claim model to relations for the return of illegally written off securities caused a negative reaction from many civilists. Although the disputes about the ownership of non-documentary papers to things, about the possibility of applying property- legal methods of protection to the return of non-documentary papers, etc. did not have a direct bearing on the problem of protecting the rights of holders of non-documentary papers (McMeel, 2017). The only practical rationale for the analogy with the vindication claim was the need to take into account the good faith of the acquirer of such papers (and this figure was thought to be inextricably linked with vindication). In other words, by analogy, only the provisions on the subjective good faith of the acquirer were applied, but not on the right of ownership and not on vindication!

Thus, problems with choosing a method of protecting infringed rights of the holder of non-documentary papers would not arise at all if the provisions on the subjective good faith of the acquirer of property from an unauthorized alienator as the basis of the rights were in the general provisions of the civil code, and would not be artificially tied to a vindication claim.

In 2013, the Russian legislation was designed to protect the violated rights of rights holders, from whose account uncertificated securities were illegally written off (article 149.3 of the civil code). This method of protection serves as an independent method of "restoration of corporate control" that is distinct from the vindication. But the new method of protection could not refuse the subjective good faith of the acquirer.

Rights to a share in the authorized capital of a limited liability company

Developing ways to protect the rights of participants in limited liability companies who lost their shares in the company's authorized capital went a different way than protecting the rights of shareholders who lost uncertificated shares (although the legal nature of uncertified shares and shares in the authorized capital are the same - these are corporate participation rights). In Russian practice, the share in the authorized capital of an LLC, as opposed to non-documentary securities, was not recognized as a thing, even indirectly - therefore, initially the possibilities for the analogy with the vindication claim were limited. The following explanation was characteristic of judicial practice, for example: «Share in the authorized capital of a limited liability company is a set of property rights and obligations of a participant in the company. Protection of the right to a share can be carried out through the methods provided for in Art. 12 of the Civil Code. The norms of civil law on the methods and conditions for the protection of property rights in these cases do not apply»15. Since article 12 of the civil code contained such a method of protection as recognition of the right, the legislator chose to protect the lost rights to share the model of the claim for recognition of the right (paragraph 17 of article 21 of the Federal Law "On limited liability companies»)16.

In accordance with the provisions of paragraph 17 of Art. 21 of the Federal Law "On LLC" conditions for the defendant to retain the right to a disputed share in the authorized capital of the LLC are: 1) the good faith of the acquisition of the share; 2) the compensation of the acquisition of a share; 3) the share was lost by the claimant against his will. Thus, these conditions form the composition of the occurrence of the right to a share in the share capital acquired from a person who did not have the right to alienate this share.

While it can be noted that in designing ways of creating corporate rights when acquiring shares from an unauthorized alienator, subjective good faith is borrowed from Art. 302 of the Civil Code of the Russian Federation in conjunction with other elements of the composition of the occurrence of the right (loss of property by the right holder against his will, the good faith of the acquirer and the punishment of the acquisition) (Ponta, 2016).

Right to share in the ownership

Sooner or later, the issue of accounting for subjective good faith "gets" to all objects of property civil rights. The share in the property right was not an exception. In fact, the share in the right of ownership is an object of property turnover, in respect of which there is practically no legal regime, very fragmentary references to certain rules are attributed to the pre-emptive right of purchase, some rules are found in very «unexpected places»17. The discussion about the legal regime of such an object of civil property rights is only gaining momentum and is actually inspired by the dubious nature of the behavior of individual co-owners of residential premises, often associated with the exercise of the right of disposal18. However, there is also the usual civil turnover, which sooner or later "throws" incidents to resolve. Such a question arose before the Supreme Arbitration Court of the Russian Federation, which, when resolving a particular case in its usual methodology, stated the applicability of the rules on subjective good faith to relationships, in connection with the protection of rights to a share in the right of ownership19.

Rights of the pledgee

The dynamics of civil turnover showed that there is also a need to take into account subjective good faith in the legal regime of absolute security rights. Perhaps this kind of example is out of the logic of the previous statement, since it is not a right that identifies the ownership of a particular object of property rights to a participant in civil turnover. However, it appears to be an illustrative example in the context of the rationale for the treatment of subjective good faith as an element of the legal regime of absolute rights and, in particular, absolute security rights20.

For the first time, the issue of accounting for subjective good faith was raised before the Supreme Arbitration Court of the Russian Federation when considering the requirements for the application of the consequences of the invalidity of the transaction and resolving the issue of the return of the subject of restitution, which until the invalidity was burdened with the rights of the pledgee retrospectively failed buyer, with the preservation of security rights or with the termination of such rights21.

The application of subjective good faith as an element of the legal regime of a pledge right was consolidated in the form of an abstract explanation in paragraph 25 of the Resolution of the Plenum of the Supreme Arbitration Court of the Russian Federation of February 17, 2011 No. 10 «On some issues of the application of pledge legislation»22 and, as the finale of the development of such accounting, - in the content of the law. Now, with respect to the bona fide purchaser of the pledged property, the pledge is terminated, the property is transferred to it without encumbrance23.

Obviously, the next stage in the development of the legal regime of the pledge right in the context under consideration will be the consideration of subjective good faith when acquiring a pledge seniority24.

Discussion

Trends in the application of subjective good faith in Russian practice.

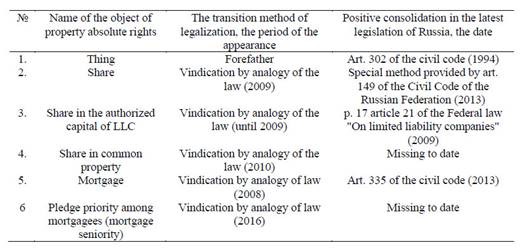

The above subjects of consideration of subjective good faith can be summarized as follows:

The above retrospective of the gradual discovery by the law and order of the need to take into account subjective good faith in regulating the relations of turnover of objects of civil property rights reliably shows that from the onset of the active phase of using the relevant objects in exchange operations to the moment of taking into account the subjective good faith of the third the object takes about 20 - 25 years. It is significant that in all cases, the prototype of the account of subjective good faith was the design related to real law, only the instrument of application of such (from a fairly simple analogy of law to a sophisticated analogy of law) was changed.

From among the objects of civil rights mentioned in Art. 128 of the civil code of the Russian Federation have no requirement in the legal regime about the account of subjective good faith as the tool of protection of the rights of participants of civil turnover only property rights, results of works and rendering services, protected results of intellectual activity and means of individualization equated to them (intellectual property) and intangible benefits. Such a sequence of listing looks somewhat curious, as if the objects of civil rights lined up for "subjective good faith", and the rule of law, when it comes time, in turn, gives such an appropriate tool.

At the same time, such an investment is not always successful. An attempt to introduce rules on taking into account subjective good faith in regulating the turnover of property rights of a binding nature turned out to be unsuccessful25. However, the discussion could not be considered complete. First, some rights of obligation are still subject to the publicity of the authorized person and have in their arsenal the means of identification of the authorized person based on transactions registered under Russian law. Secondly, it is conceivable to establish such a sign by the rule of law, in particular, the so-called accounting registration very successfully performs such a function in relation to the pledge of movable things26.

Conclusion

It is obvious that there is no need to take into account subjective good faith in the construction of legal regimes for the results of works and services in the same sense in which such is taken into account in respect of appropriated familiar discrete objects that are valuable in themselves and in respect of which the exercise of rights is conceivable outside the relative creditor - debtor relationship. The current state of legal regulation, as well as the content of social relations, do not allow us to talk about the fact that there is a need for discussion of such an issue with respect to intangible goods. In the case of the latter, it is rather seditious to judge whether it is permissible to exclude the restoration of the right in kind by reference to the characteristics of the conduct of the "acquirer" or "illegal user" (if at all it is appropriate to speak of the acquirers of any rights in respect of intangible goods). Rather, in respect of the intangible benefits of the mode versasuite, which in all cases is permissible, and probably inevitable natural restoration of the rights, the interests of third parties, acting perfectly, is relevant instruments of tort law.

Such judgments allow us to put a rhetorical question: "who is next?" which seems to have an obvious answer. Subjective good faith in Russian law expands its scope and, without a doubt, should be applied in relations arising in connection with the establishment, circulation and protection of exclusive rights in intellectual property.