Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Propósitos y Representaciones

versión impresa ISSN 2307-7999versión On-line ISSN 2310-4635

Propós. represent. vol.10 no.2 Lima may./ago. 2022 Epub 31-Ago-2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.20511/pyr2022.v10n2.1505

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Project Based Learning and Epistemological Development on Undergraduate Students

1 Universidad de las Américas Puebla, Puebla, México

This paper is part of a bigger research that aims to understand how professional education delivered through Project-Based Learning (PBL) affects self-authorship development on undergraduate students. This part of the project aims to evaluate self-authorship development of undergraduate students enrolled on PBL during four to five years. The method used was qualitative, transversal, with biographical-narrative approach. In deep interviews were the instrument for data construction. Nine students of different semesters voluntarily participate on the interviews. Data analysis were based on categories validated on previous research, using the software Atlas.ti as a tool. Results found that practical experience during professional education would exert different effects on students depending on their self-authorship position. In addition, found that PBL on its own is not sufficient to generate movement to more sophisticated self-authorship positions, but it can support incipient movement underway.

Keywords: Cognitive development; College students; Autonomy; Teaching methods; Project Based Learning

Introduction

This paper stems from a concern shared with colleagues: Is it possible, as educators or as an educational institution, to support the epistemological development of students? Those who work in higher education probably faced, at some point, the students’ concern to discover, among all the theories presented in class, which one is the correct one, or stumbled over their difficulty in arguing effectively about some ill-structured problem discussed in class. Students seem to expect precise answers regarding how to act both in their professional and in their personal lives, how to make decisions, and what the right way to solve ill-structured problems is. This is possibly a consequence of their difficulty in recognizing and dealing with uncertainty. In other words, it is the result of the particular way in which these youths make sense of their experiences and knowledge: their self-authorship.

Self-authorship refers to the ability to construct beliefs, learn and make decisions based on an internal foundation and is made up of three dimensions: interpersonal (relationships with others), intrapersonal (identity, decision-making, self-perception), and personal epistemology (beliefs about the nature, source and limits of knowledge). Research with undergraduate students has shown that the youth evolve from an absolutist position, dependent on external expectations and beliefs, towards an increasingly autonomous attitude in their decision making, self-view, learning, and problem solving within their profession (Baxter, 2004). It has also been found that as students move on in self-authorship, they also begin to hold a more independent stance in their personal lives, self-perception, and relationships with others (Abes et al., 2007; Bennett & Hennekam, 2018; Laughlin & Creamer, 2007; Williams, 2016; Zaytoun, 2005). Moreover, they rely less and less on legitimized models to think, act, and plan for the future (Bontempo & Flores, 2016, 2017; Creamer & Laughlin, 2005; Flores et al., 2010; Lewis et al., 2005). Conversely, as they move towards more complex positions of self-authorship, young people exhibit more stable professional identity and greater commitment to their professional training (Bennett & Hennekam, 2018; Williams, 2016).

Unfortunately, it has been reported that most undergraduate students, from different contexts, are in the early stages of self-authorship (Bontempo & Flores, 2016; Creamer & Laughlin, 2005; Flores et al., 2010; Lewis et al., 2005). This means that, in their professional training, they are dependent on legitimized sources (e.g., professors, books, culture) and pre-established models to solve problems and, even, to make decisions about their own lives.

This brings us back to the situation initially proposed: students who cannot understand explanations that contradict each other or students who are unable to evaluate or apply knowledge in a real context. Now we see them as people who, even if they want to do it and make an effort and study hard, cannot do it, because they are identified with the perspective of authority, with the “truth” that will be transmitted to them in class, and the manual of how to act in life. They need to de-identify themselves in order to relate to knowledge and to what they perceive as authority. Therein lies the challenge.

Self-Authorship

The concept of self-authorship was initially proposed by Kegan (1982), as the “skill” that, when developed, would mark the end of adolescence and the beginning of adulthood. This ability would enable adolescent-adults to critically reflect, to make decisions based on their ideas and will. Thus, they would be freed from the expectations and beliefs of others and from the need to step aside in order to belong and be accepted (a very common quality in adolescence).

Baxter (2004) adopts this concept and deepens it in its relationship with personal epistemology, which until then she studied, in the line of work of Perry (1970). The author defines self-authorship as “(...) the ability to collect, interpret, and analyze information and reflect on one’s own beliefs in order to form judgments” (Baxter, 1998, cited in Baxter, 2004, p. 14)1. In his model, development is non-linear and may vary in specific domains, i.e., a person may reflect autonomously in his or her professional training, but not in his or her intimate relationships. Moreover, development is not predictable, and may or may not occur, or even can (and usually does) happen in very different ways for each individual (Baxter & King, 2012).

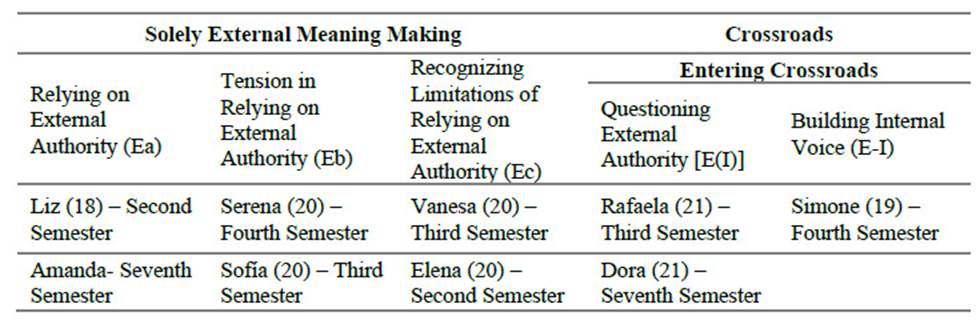

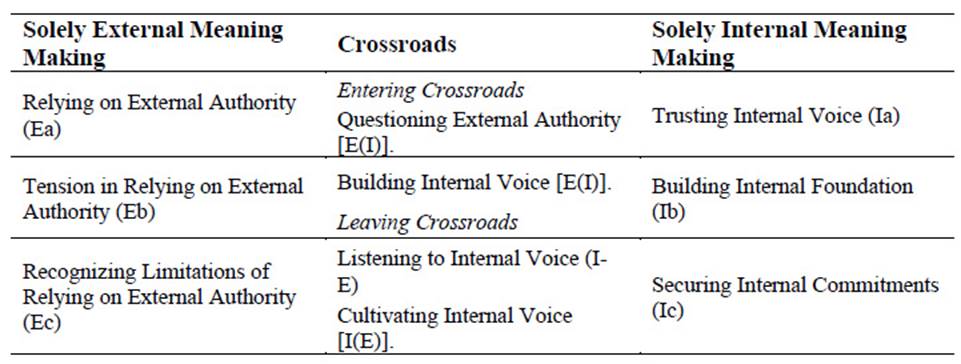

Developmental movement occurs in the interplay between three dimensions: epistemological, intrapersonal and interpersonal, and generates a progression from a perspective that relies entirely on externally validated formulas for thinking and acting, to the ability to formulate one’s own judgments. This movement is described in a continuous trajectory in which there are three major positions: Solely External Meaning Making, Crossroads, and Solely Internal Meaning Making. These three are comprised of intermediate positions, making a total of ten, as shown in Table 1. First, Solely External Meaning Making is divided into three, where all meaning making is based on external formulas. Then, Crossroads is comprised of four transitional positions. Finally, Solely Internal Meaning Making, which is made up of three positions, is the stage where students become confident and secure in their own rationale (Baxter & King, 2012).

Table 1 Development of Self-Authorship

Source: Baxter, & King, 2012, pp. 19 (Adapted from Baxter, & King (2012), originally in English).

The shift from one position to the next is not automatic, depending always on the context. As it is a constructivist perspective, it understands that development occurs when a situation of imbalance is presented to which the individual cannot cope with the tools that he/she possesses. Thus, an appropriate context for development must represent an ideal challenge to the individual, not being so big that he/she cannot solve it, nor so small that he/she cannot find motivation to build new tools. At the same time, it must offer them a progressively decreasing support (Delval, 2014).

According to background literature, schools (Bontempo & Flores, 2016, 2017) seem to offer a safe and stable environment in which young people can be supported to evolve in their self-authorship. Furthermore, different authors agree that it is important to build programs (both curricular and extracurricular) in undergraduate that support the development of young people (Baxter & King, 2012; Bushnell & Henry, 2003; Carpenter & Vallejo, 2017; Case, 2016; Coughlin, 2015; Creamer & Laughlin, 2005; Day & Lane, 2014; Del Prato, 2017; Kenner, 2019; Laughlin & Creamer, 2007; Myers, 2017; Reybold, 2002; Sandars & Jackson, 2015; Zaytoun, 2005).

Baxter and King (2004) propose a companion model to support the development of self-authorship; this model can serve as a basis for tutoring or mentoring activities as well as for developing curricular and extracurricular teaching-learning activities. This model, called the Learning Partnership Model (LPM), is based on three assumptions: (1) knowledge is socially constructed; (2) the self is central to knowledge construction; and (3) authority and expertise are shared in knowledge construction (Baxter & King, 2004). Therefore, the authors suggest the adoption of three fundamental practices for the promotion of self-authorship: (1) validating the role of the learner as an active knower; (2) situating learning in the learner's experiences, and (3) starting from the assumption that knowledge is a construction of meaning that occurs collectively (Baxter & King, 2004)

Extracurricular activities based on the learning partnership model (LPM) that, with the objective of minority inclusion (Clark & Brooms, 2018; Mondisa & Adams, 2020; Orozco & Pérez-Felkner, 2018), have shown good results in supporting the development of students' self-authorship and the construction of their identity, as well as for adaptation to the context and, even, for the decrease of school dropout (Clark & Brooms, 2018; Mondisa & Adams, 2020; Orozco & Pérez-Felkner, 2018). In the same way, educational practices based on LPM and on the situated and practical nature of learning have also shown positive results as support for the development of students’ self-authorship (Johnson, & Chauvin, 2016; Ricks et al., 2021) and in the formation of professional identity (Johnson, & Chauvin, 2016).

In addition, other authors have concluded that it is critical for learning to be situated and for there to be a balance between the challenges and support offered to students (Day & Lane, 2014; Kenner, 2019; McGowan, 2016; Sandars & Jackson, 2015). Pizzolato (cited in Day & Lane, 2014) notes the importance of dissonant experiences, culminating in the provocative moment, to support the transition to more sophisticated ways of thinking. Such provoking moments can arise from the student-professor relationship (Ricks et al., 2021), from challenges arising when adapting to context, especially for minorities (Orozco & Perez-Felkner, 2018; Clark & Brooms, 2018; Mondisa & Adams, 2020), from challenging experiences in which the youth need to take action and make difficult decisions (Johnson & Chauvin, 2016).

A well-established constructivist methodology that seems to combine all the aforementioned characteristics is Project Based Learning (PBL). PBL is a methodology that has gained importance in recent years, despite having its origins in the second half of the 19th century (Cyrulies & Schamne, 2021; González-Ferriz, 2021). Similar to problem-based learning, the main difference is that project-based learning focuses learning on research or intervention projects in real and, generally, poorly structured contexts (González-Ferriz, 2021; 37). Thus, project-based learning:

“(…) is characterized by presenting a globalized problem that needs research to be solved, by collaborative work, by the link between reality and school, as well as by the students’ leading role in the whole learning process, in decisions regarding contents and in evaluation. As opposed to the mere transmission of knowledge, PBL has involved the implementation of shared tasks among participants to respond to the problem initially posed” (Salido, 2020, p. 122).

Students choose the context, the objectives of the project, the theoretical framework, so that the professor and the curriculum function as moderators and guides in the learning process (Rodríguez-Sandoval et al., 2010). Hence, the responsibility for learning is distributed among the different actors: institution, professor and student. In addition, it enables greater motivation for students, who choose topics and contexts that are of interest to them (Botella & Ramos, 2020; Mozas-Calvache & Barba-Colmenero, 2013). Another advantage of PBL is its interdisciplinary nature, due to the fact that solving a real problem always involves different disciplines and different skills (Cyrulies & Schamne, 2021; Mozas-Calvache & Barba-Colmenero, 2013). It also facilitates the transfer process, since students have to apply the contents studied to solve real problems (Cyrulies & Schamne, 2021). Lastly, this methodology encourages teamwork and collaborative learning (Cyrulies & Schamne, 2021; González-Ferriz, 2021; Mozas-Calvache & Barba-Colmenero, 2013; Salido, 2020).

Therefore, Project-Based Learning integrates the three elements mentioned by Baxter and King (2004) as fundamental to support the development of self-authorship (validation of the student’s role, situated learning, and the collective nature of knowledge construction). Thus, the potential of this methodology, when used in the long term, to support students in developing more sophisticated ways of thinking and acting professionally and personally is identified.

In conclusion, I return to the problem posed at the beginning, now in a slightly more contextualized way: what effects will an undergraduate program based on PBL have on the development of student self-authorship?

Method

This article reports the results of a qualitative study with a biographical-narrative approach. Considering that, for the objectives of the study, this methodological framework is the most appropriate, since qualitative research is understood here as that which is oriented to the in-depth understanding of phenomena, which uses a more conceptual language, is based on constant reflection and revision during the research construction process, does not start from pre-established hypotheses, and approaches the phenomena in a contextual manner (Ruiz, 2009; Sandín, 2003).

The biographical-narrative approach is a combination of the biographical approach and the narrative method and focuses on life stories from a perspective centered on the narrative construction of reality (Bolívar & Domingo, 2006). The use of this approach is justified by the need to give voice to the participants, listening to their perspective, and trying to understand, really, their way of making sense of their experiences. Although it focuses on biographical experience, it is not a life history.

Participants

The study population is composed of students of a Bachelor’s degree in Educational Innovations at a highly recognized private university in Mexico. This degree is based on the ABP methodology, so that it is organized in modules, in which, first, a diagnosis must be made from the systematic observation of a real context. Subsequently, an intervention project is proposed and implemented in the observed context. All the specific subjects of the course are connected and are constructed and evaluated according to the ABP.

The sample was selected theoretically and by convenience. Theoretically, because we needed students from an undergraduate degree whose program was based entirely on project-based learning, being present in the entire organization of the degree and in the individual structure of the specific subjects of the degree, which make up the curriculum. The sample was selected by convenience, so that the students enrolled in the mentioned career and who were interested in participating participated, responding to an invitation made to all the enrolled students.

Ten volunteers2, were interviewed, all women, aged between 18 and 21 years. Of the 10 interviews conducted, only 9 could be analyzed due to problems in the audio recording of one of them. The participants were between the second and seventh semester of their training, representing a cross-sectional sample, with students recently entered, some in mid-career and others about to graduate. The cross-section offers a description of how the studied population evolves in relation to a variable, in this case, the academic trajectory in the bachelor's degree.

The main limitation of the sample is the exclusivity of female participants. On the other hand, this reflects the undergraduate population in this context, which is generally composed of more women than men.

Procedure

The construction of the information was carried out through in-depth interviews about the life experiences of the participants, both about their personal and family life, as well as their academic life. The interviews were developed based on Piaget’s clinical method (Delval, 2014), in Baxter's (2004) self-authorship interview. In this way, the interviewer formulates initial hypotheses, based on the answers and stories of the interviewee, these serve to formulate the following questions in a way that makes it possible to test the hypothesis and eliminate the possibilities that the participant's thinking is placed in the next or previous position.

In order to conduct such an interview, a thorough knowledge of the self-authorship model is necessary. It is not possible to make a diagnosis by the interview alone; in-depth analysis is necessary afterwards, but the interview is an important tool for data construction. The in-depth interview method has proven to be the most effective for research on self-authorship, despite the existence of quantitative instruments that enable research with larger samples (Baxter & King, 2012).

As Gibbs and Widaman (1982); King (1990); and Rest (1979) state:

Researchers have shown that structure becomes visible when interviewees are invited to construct a response or actively construct meaning by answering a question. When interviewees have to choose an answer among options offered to them (called a recognition task) they usually show preference for answers they are not yet able to produce (as quoted in Baxter & King, 2012, p.22)3.

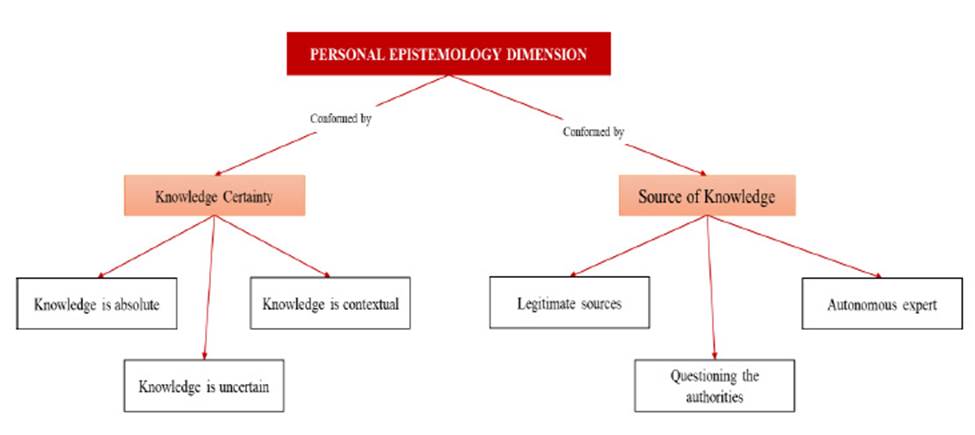

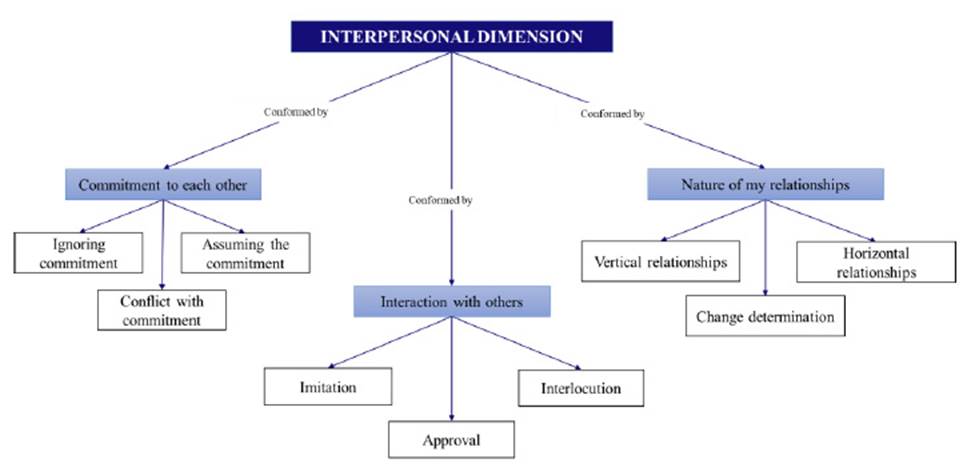

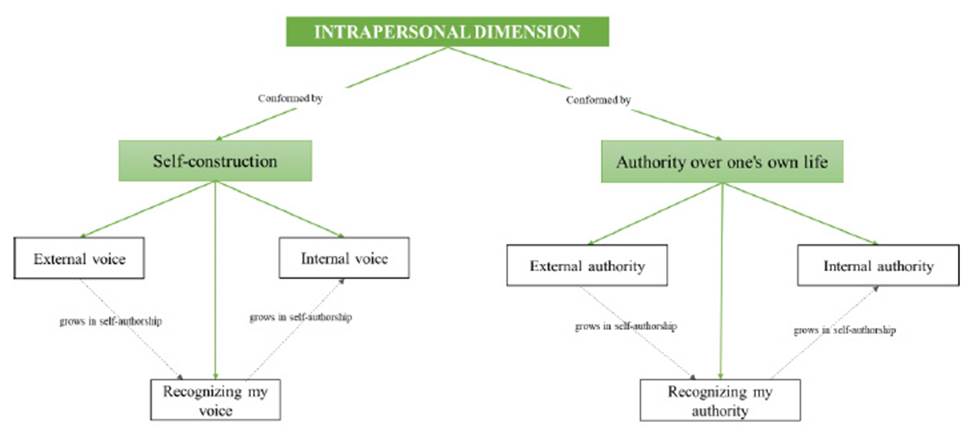

The interviews lasted about an hour and were audio-recorded, then transcribed. The transcripts were analyzed in depth using Atlas.ti software. Initially, a line-by-line open coding of the information was performed, labeling phenomena that seemed important, but without predefined categories, a process called conceptualization (Corbin & Strauss, 2015). In this process, any element that could be relevant to understand how participants make sense of their experiences and the complexity of their epistemological beliefs was labeled. At the same time, it was categorized based on the validated categories of the instrument “Written accounts of self-authorship” (Bontempo & Flores, 2016). These categories are organized within three dimensions: intrapersonal, interpersonal and personal epistemology. Within each one there are groups of categories and subcategories that were designed and validated in previous research with a population similar to that of the present study, the reliability of these was 79.6% in the Krippendorff’s alpha coefficient (Bontempo, 2014; Bontempo & Flores, 2016). As a criterion of rigorousness in the interpretation, researcher triangulation was used, comparing the interpretation of three researchers who are experts in the subject and external to this specific study. In this case, the level of agreement in the Krippendorff’s alpha coefficient was 81.3%.

The dimensions and categories used are organized as shown in Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Considering that the purpose of this paper is to describe how the two variables are related and how the evolution of the meaning construction activity occurs, rather than to affirm whether there is a relationship between them, the sample and the instrument chosen were appropriate. Once the information was categorized, we sought to understand and describe how each participant makes sense of what she lives and what she learns, as well as her perception of the career and its curricular design. All the while comparing the participants among themselves, as well as comparing the results with the model of Baxter and King (2012) and with the antecedents in Mexican population (Bontempo, 2014; Bontempo & Flores, 2016, 2017).

Note: Adapted from “Reflexive Identity and Self-Authorship among Psychology Students at UNAM” (pp. 87) by Bontempo, 2014 4

Figure 1 Personal Epistemology Dimension

Note: Adapted from “Reflexive Identity and Self-Authorship among Psychology Students at UNAM” (pp. 94) by Bontempo, 2014

Figure 2 Interpersonal Dimension

Note: Adapted from “Reflexive Identity and Self-Authorship among Psychology Students at UNAM” (pp. 102) by Bontempo, 2014

Figure 3 Intrapersonal Dimension

Results

Comparing the sample, in general, against the positions described by Baxter and King (2012), it was found that the participants are in the first two major positions: Solely External Meaning and Crossroads, specifically, entering Crossroads (as shown in Table 2).

Note, however, that this comparison does not perfectly describe the sample. After all, although for the most part the positions mentioned are comparable, in the sample studied in the present research it responds differently in specific dimensions, mainly in terms of personal epistemology. It is possible that the differences are due to cultural aspects, due to the fact that it is more similar to the responses of the sample of Bontempo and Flores (2016, 2017).

Thus, this research describes an evolutionary movement that begins with changes in the intrapersonal dimension, with the awareness of the need to take responsibility for their decisions. The last dimension to change is, almost always, the epistemological one, which is in agreement with the results reported by Bontempo and Flores (2016). On the other hand, it differs from the results reported by Baxter and King (2012), who, on the contrary, describe the change starting with the personal epistemology dimension.

Relying on External Authority (Ea)

From Table 2, we can see that the two participants in the initial position (Relying on External Authority) are at different points in their careers, despite being very close in age. Both have something in common: very traditional families that exert a great deal of power over them. Neither mentions an experience close to what Pizzolato (cited in Day & Lane, 2014) calls dissonant experience.

Both Liz (second semester) and Amanda (seventh semester) fail to perceive uncertainty, always justifying themselves based on stereotypical ideas that they cannot really explain, both in their professional training and in their personal lives. For example, Liz worries about her sister because she “knows” that she is doing things wrong:

“(…) I have seen that my sister follows the steps of my dad, and I follow the steps of my grandpa; and they are different. My dad is very much a womanizer and my grandpa is a one-woman man. So, because of this, I feel like I have to take care of her. I really think that she is making a mistake in choosing her partners. And it gives me a lot of pain, because I always imagined my brothers with family, and she doesn't want this at all. I wouldn't want her to be alone, or with someone who doesn't know how to value her” (Liz, 18).

Relying on External Authority (Ea)

From Table 2, we can see that the two participants in the initial position (Relying on External Authority) are at different points in their careers, despite being very close in age. Both have something in common: very traditional families that exert a great deal of power over them. Neither mentions an experience close to what Pizzolato (cited in Day & Lane, 2014) calls dissonant experience.

Both Liz (second semester) and Amanda (seventh semester) fail to perceive uncertainty, always justifying themselves based on stereotypical ideas that they cannot really explain, both in their professional training and in their personal lives. For example, Liz worries about her sister because she “knows” that she is doing things wrong:

“(…) I have seen that my sister follows the steps of my dad, and I follow the steps of my grandpa; and they are different. My dad is very much a womanizer and my grandpa is a one-woman man. So, because of this, I feel like I have to take care of her. I really think that she is making a mistake in choosing her partners. And it gives me a lot of pain, because I always imagined my brothers with family, and she doesn't want this at all. I wouldn't want her to be alone, or with someone who doesn't know how to value her” (Liz, 18).

In this quote we can see how she thinks that there is a better way to live, and that her sister is making a mistake by choosing the other way. Thus, she constructs her role in the relationship by identifying with authority.

In addition, both Liz and Amanda perceive practice, in professional training, as an opportunity to ground theoretical knowledge, exemplifying it, confirming it and facilitating learning. Amanda, when talking about the curriculum in her career, mentions that she liked doing projects a lot, because she could get out of the theory a little and see it applied, however, she says it was not easy:

“I like it because it does make you work and understand things. It's not just theory and that's it (...) was to relate things to each other. Now, applying what I was seeing in class and applying it in practice” (Amanda).

Liz and Amanda do not take an active stance in their decisions, allowing themselves to be led by the expectations and will of others, especially people they consider relevant. Also, the opinion and acceptance of others, even strangers, is very important to them. Liz comments that she is overwhelmed by the pressure she feels to be accepted:

“(…) I don't know how to engage in conversation. It's too much... If I say something, the conversation will end and we won't talk anymore. So, I have to think and... act fast... Then, by acting fast, bad things happen. (...) When do I get to be myself? Hmm... Honestly, never” (Liz, 18).

As we can see, Liz is so concerned about the acceptance of the other that she feels she is unable to be herself. So was Amanda, who, despite already being in her seventh semester, showed a way of perceiving the world and relating to it that identified with the first position.

According to Baxter and King (2012), the main difference between the first and second positions is that, in the second position, one begins to recognize the dilemmas that arise from seeing knowledge as certain and in relying on the external voice to define oneself and decide about one's own life. Thus, in the second position, Tension in Relying on External Authority (Eb), are Sofia (third semester) and Serena (fourth semester), both 20 years old.

Tension in Relying on External Authority (Eb)

Sofia says she is going to attend college in Mexico City and is faced with a very difficult reality. She has always been alone and has not found a way to build meaningful relationships. Sofia was still very attached to her family and friends back home. This time of uncertainty could have resulted in an important moment of transition. However, although she really liked the career she was studying, she preferred to abandon it and change to another one that was not exactly what she wanted, in order to be closer to her friends

“(…) I really liked the career I was studying. But I had friends here in Puebla (...) and I saw them going out every day, having fun, all together. All of my high school friends came here. So, I had to decide whether to stay in the career I liked or go to a similar career in an environment where I would be happier” (Sofía, 20).

Sofia begins to make her decisions, but based on external models, such as the happiness shown by her friends in Puebla, while she, in Mexico City, did not experience the same. Even though she seems to be very clear about what she wants to study, she does not manage to build the necessary independence to leave aside the need for her family and to be close to her friends.

Serena experienced the problem of relying on external authority in her own skin. Even when she was clear that she did not want to go on exchange, she could not assert herself in her relationship with her mother and ended up going. After a while, when she could no longer be there, she told them that she wanted to go back. She recognizes the need to listen to her own will, but she is still too worried about people’s approval, especially her mother's.

At the same time, Serena and Sofia begin to recognize uncertainty in some areas of knowledge. This creates tension for them, so they seek to eliminate it quickly, so they either ignore it, assuming that there is only one right answer, or they rely on another authority to eliminate it, or they even classify two types of knowledge: opinion and knowledge, as we see in this section of the interview with Sofia

“I mean, everyone can think differently and there is nothing wrong with that, but when it comes to knowledge, well, then, someone certainly has to be right and the other wrong” (Sofía, 20).

In their personal relationships, they are very focused on being accepted. For example, when a conflict arises, Sofia prefers not to disagree, assuming a passive role and avoiding the source of the conflict. Telling about a situation when two professors contradict each other on a particular subject, Sofia affirmed:

“(…) I already know what the first professor said, so I would tell this second professor: ‘It is not like you say it is.’ And if this professor tells me: ‘No, it is not the other way you were told’, well (...) I’d just stick with what each professor says; I’d apply in Professor A’s class what Professor A says, and in Professor B’s class what Professor B says.” (Sofía, 20)

Hence, it seems that there is no possibility of dialogue, especially with authority, because she perceives that when she does not agree, she has to keep quiet and submit to the authority of the one who occupies it, in this case, the professor.

In the end, Serena and Sofia exhibit the main characteristics of the position Tension in relying on external authority (Eb), which are: “discomfort in the face of uncertainty, little clarity about their own perspective, and sense of obligation to live under the expectations of others”5(Baxter y King, 2012, pp. 61).

Recognizing Limitations of Relying on External Authority (Ec)

Acceptance of uncertainty as well as recognition of the need to form their own opinions and make their own decisions grows as they approach the next position: Recognizing Limitations of Relying on External Authority (Ec). In this position, we identify Elena and Vanessa.

In Elena’s case, she gradually made decisions that brought her into more complex contexts and led to changes in her self-authorship. She decided to change schools, going against her parents' expectations. Then, she decides to go to another country to do volunteer work, also against her parents' will and expectations. In both cases, she finds herself in challenging contexts, having to adjust her way of perceiving reality and herself, broadening her worldview and necessarily moving her from an absolutist epistemological perspective to a more relativistic one. Returning, she chooses to break with what everyone expected of her and decides to study Pedagogy instead of Law, which on the one hand is an act of recognizing her own voice, but on the other hand generates conflict with disappointing her parents.

Vanessa, in turn, finds the opportunity for growth by moving away from the town where she lived and, with this, she frees herself from the labels that defined her, as we see in this quote

“Here nobody watches me, nobody thinks of me as ‘Vane, the daughter of so-and-so, is doing good or bad in school.’ I mean, no. It’s like ‘Vane, I'm Vane, call me Vane.’ And I like that, I like the fact that I can be myself without being judged (…)” (Vanesa, 20)

Elena and Vanesa recognize the need to take an active role in their own lives, and strive to do so by seeking to make decisions that are based on what they want, separating themselves from the expectations and opinion of the other. However, they are not yet able to do so. They worry about disappointing their parents, being accepted by their friends, and avoid conflict in relationships for fear of what they will think.

About their view on knowledge, they can perceive uncertainty in some fields of knowledge, such as in the social sciences, as opposed to the other sciences. In life, they do not perceive uncertainty, as they justify themselves based on stereotyped views. When faced with ambiguity, they assume that all are points of view and all are valid, as Elena says

“(…) both being very professional and knowing everything they know, why do they have such a different perspective? I mean, they are opposite in something so... something that could seem simple, right? (...) It is not so much about who is right and who is wrong, because at the end of the day there are going to be two positions (…)” (Elena, 20)

Finally, both Elena and Vanessa, as well as Serena and Sofia, lived disruptive experiences that “pushed” them to the transit they lived. These were personal experiences in which they had to face alone a reality very different from their own. However, they are still dependent on external influence. When talking about the importance of practice, all of them (Liz, Amanda, Sofia, Serena, Vanessa and Elena) have a similar idea: practice grounds theory, serves to confirm it and make it clearer

Questioning External Authority

Crossroads marks the exit from the construction of meaning based on external formulas, and in the first part of this position, the internal construction of meaning begins to emerge, but it is still incipient. In the first position, Questioning External Authority, individuals still rely on external formulas, but begin to question the way others think and act. Through this process, they begin to construct their own way of thinking, acting, seeing themselves and relating to others.

In this position, we identified two students: Dora (21 years old and seventh semester) and Rafaela (21 years old and third semester). Both can recognize the uncertainty of knowledge and already feel more comfortable with it. They recognize the possibility of learning from the perspective of the other, not only from the authorities, because they see that by listening to the other, they can question their own perspective. When talking about the relationship between theory and practice, they perceive, on the one hand, that practice brings down to earth and exemplifies what they have learned in class. On the other hand, they can see that it often contradicts it and that when intervening or explaining a specific context, theoretical knowledge must be relativized. As Dora told us about her experience with the projects:

“(…) We really lived it and returned to class (...) We would discuss any problem in class and we would find the answer as a class and together with the professor” (Dora, 21).

Contrary to other cases, there does not seem to be an event that drives Dora’s and Rafaela’s development. Rather, it seems to be a gradual process in which their experience at the university plays an important role. In Rafaela’s case, political participation by assuming a student leadership position led her to perceive what it is like to face the problems of the “real world,” as she puts it. In Dora’s case, the practical interventions they do for the program's subjects led her to feel more confident to act and present her point of view, and also led her to listen to the other’s perspective and take it into account.

Building an Internal Voice

Finally, Simone (19 years old and in her fourth semester) is in the Building Internal Voice position. Unlike Dora and Rafaela, Simone begins to actively build her internal voice, which often conflicts with the external voice. In Simone’s case, the external voice is present by constantly comparing herself to others, and by worrying about what they think of her. Regarding her view of knowledge, she recognizes and accepts uncertainty, in the practice of her profession and in life. When confronted with ambiguity, she mentions that she sometimes contextualizes knowledge, and sometimes turns to authorities to eliminate it.

In her case, what seems to have worked as a dissonant experience was her practice as an adult educator in rural Mexico. With this, she broadens her vision of the world, in addition to living uncertainty on a daily basis in her practice. In this way, she began to construct, herself, her teaching strategies that were appropriate to different contexts, as she mentions below

“(…) In some contexts, Freire’s method did work for me. (...) Not so much for certain contexts, but I was able to find a way. I mean, they have to learn, no matter how, but they have to learn (...) So learning is personalized at the pace of each person” (Simone, 19).

In this way, she perceives that practice is not the exemplification of knowledge, but presents its own challenges, which imply a construction of the learner contextualizing theoretical knowledge.

Discussion

After analyzing all the participants, the first thing that stands out is that progress in self-authorship does not seem to have any relationship with age, as mentioned by Baxter and King (2012). Also, in accordance with what was shown by Baxter and King (2012), the evolution of self-authorship is nonlinear, so that it could be more comparable to a wavelike movement. Nor was it possible to identify an evolution that was related to the academic trajectory; the cases of Amanda and Simone are the most representative, in this sense. Amanda, in spite of being out of college, is still in the first position of the studied model. Simone, on the other hand, studying the fourth semester, that is, in the middle of her professional training, is the only one identified in the position Building an Internal Voice.

Returning to the guiding question of this paper, the undergraduate program based on PBL, although it leads to greater confidence in their professional practice and helps the process of knowledge transfer (from theory to practice), does not seem to have a direct relationship with the evolution of students’ self-authorship. What seems to happen is that the meaning that students will give to their practical experiences will depend on the position in which they find themselves. While some will see it as something that makes theoretical knowledge tangible, others will see it as something that leads them to construct knowledge in the practical context.

Thus, the evolutionary movement of young people seems to be more motivated by challenges that involve them emotionally, interpersonally, and cognitively, or dissonant experiences (Amechi, 2016; Case, 2016; Day & Lane, 2014; Johnson, & Chauvin, 2016; Ricks et al., 2021), such as exchange, or working with socially excluded communities, or entering political activism. These experiences represented important challenges to the participants, leading them to question their way of thinking and acting, and mainly, leading them to question the authorities and to trust their own judgment. The results are in agreement with what other authors found in previous research on self-authorship, supporting that the evolution of self-authorship is related to dissonant, provocative and challenging experiences (Amechi, 2016; Carpenter & Vallejo, 2017; Clark & Brooms, 2018; Day & Lane, 2014; Johnson, & Chauvin, 2016; McGowan, 2016; Mondisa & Adams, 2020; Orozco & Pérez-Felkner, 2018; Ricks et al., 2021).

Conclusions

Finally, we can conclude that schools, despite having a structuring role (Bontempo & Flores, 2017), do not seem to be, in isolation, capable of generating change from one position to the other. Schools are more effective as generators of change when students are already in a transitional position. This does not mean that programs designed to support the construction of critical and autonomous thinking in students are irrelevant.

In this work, all participants agreed that going to a real context to observe or intervene helped them to better understand the theory, make useful sense of it, and become motivated (especially in students who were in initial positions), in line with what other researchers have found (Cyrulies & Schamne, 2021). Students who were already in more complex self-authoring positions seemed to be able to rely more on their practical experiences to question authorities and understand that there is uncertainty, that there are no manuals for everyday life or for their professional performance. They also mention that it supported them to become increasingly confident in their own judgment and, at the same time, to be able to listen to each other's feedback and opinion to rethink their perspective.

In terms of the practical implications of this study, it is clear that, in itself, a curriculum does not have the power to generate an evolutionary movement in student self-authorship. However, it can provide opportunities for them to make the evolutionary moves they are ready to make. In this way, the holistic formation of the student must be prioritized. In addition to a curriculum that stimulates and supports the development of autonomous thinking, such as PBL, it is important to stimulate student participation in extra-curricular activities and community outreach and support. In short, it is necessary to stimulate student participation in any activity in which they should live challenging experiences that push them to get out of their comfort zone and to experience the world and be affected by it, professionally, emotionally and cognitively. Experiences that lead them to construct new ways of solving problems, of perceiving the world and themselves.

It is important to mention that the present study has an important limitation, mentioned in the Method section, which is the sample composed exclusively of women. As mentioned above, the population of the Bachelor's Degree in Pedagogy is usually composed of more women than men. However, it is advisable to conduct studies in which both genders are included in order to make comparisons and observe if there are differences. It could even be studied in other degrees, such as medicine and engineering, where the PBL method is usually recommended.

Furthermore, as a qualitative study, this work describes the process well, but the results cannot be generalized because the sample is small. The in-depth interview is a slow technique and more appropriate for smaller samples, however, it offers more effectiveness in understanding the participants' thinking. Therefore, to cover larger samples, while maintaining the reliability of the results, a combination of quantitative and qualitative methods should be used, with structured questionnaires.

Likewise, this study focuses on describing the evolutionary process of students in a specific career and educational model. It does not offer a comparison with other educational models or with other careers. Thus, studies that seek to compare students from different educational models, in the same degree, would be advisable, as well as studies that compare students from different careers in similar curriculum models

REFERENCES

Abes, E. S., Jones, S. R., y McEwen, M. K. (2007). Reconceptualizing the Model of Multiple Dimensions of Identity: The Role of Meaning-Making Capacity in the Construction of Multiple Identities. Journal of College Student Development, 48(1), 1-22. doi: 10.1353/csd.2007.0000 [ Links ]

Amechi, M. H. (2016). “There’s no autonomy”: Narratives of Self-Authorship from Black Male Foster Care Alumni in Higher Education. Journal of African American Males in Education, 7(2), 18-35. http://journalofafricanamericanmales.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Amechi-2016-Black-Males-Self-Authorship-Final.pdf [ Links ]

Baxter, M. (2004). Making their own way: Narratives for transforming higher education to promote self-authorship. Sterling: Stylus Publishing, LLC. [ Links ]

Baxter, M., & King, P. (2012). ASHE Higher Education Report 38(3), 1-138. Wiley Online Library. doi: 10.1002/aehe.20003 [ Links ]

Baxter, M., & King, P. M. (2004). Learning partnerships: Theory and models of practice to educate for self-authorship. Sterling, VA: Stylus. [ Links ]

Bennett, D., & Hennekam, S. (2018). Self-authorship and Creative Industries Workers’ Career Decision-making. Human Relations, 71(11), 1454-1477. doi: 10.1177/0018726717747369 [ Links ]

Bolívar, A., & Domingo, J. (2006). La Investigación Biográfica y Narrativa en Iberoamérica: Campos de desarrollo y estado actual. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 7(4). http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/161/358 [ Links ]

Bontempo, L. (2014). Identidad Reflexiva y Auto-Autoría en Estudiantes de Psicología de la UNAM. [Tesis de doctorado Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México]. Repositorio Institucional, http://132.248.9.195/ptd2014/julio/0715729/0715729.pdf [ Links ]

Bontempo, L., & Flores, R.C. (2016). El Desarrollo de la Auto-Autoría en Estudiantes de Psicología de la UNAM. Revista de Psicología de la Ibero, 24(1), 30-37. http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=133947583004. [ Links ]

Bontempo, L., & Flores, R. C. (2017). Reflexive Identity and Self-authorship Development on Psychology Students. Journal of Education and Human Development, 6(2), 148-156. doi: 10.15640/jehd.v6n2a16. [ Links ]

Botella, A. M., & Ramos, P. (2020). Motivation and Project Based Learning: an Action Research in Secondary School. REMIE - Multidisciplinary Journal of Educational Research, 10(3), 295-320. doi: 10.447/remie.2020.4493 [ Links ]

Bushnell, M., & Henry, S. E. (2003). The Social Foundations Classroom. Educational Studies, 34, pp. 38-61. doi: 10.1207/S15326993ES3401_4 [ Links ]

Carpenter, A. M., & Vallejo, E. (2017). Self-Authorship Among First-Generation Undergraduate Students: A Qualitative Study of Experiences and Catalysts. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 10 (1), 86-100. doi: 10.1037/a0040026 [ Links ]

Case, J. M. (2016). Journeys to Meaning-Making: A Longitudinal Study of Self-Authorship among Young South African Engineering Graduates. Journal of College Student Development , 57(7), 863-879. doi: 10.1353/csd.2016.0083 [ Links ]

Clark, J. S., & Brooms, D. R. (2018). “We get to learn more about ourselves”: Black Men’s Engagement, Bonding, and SelfAuthorship on Campus. Journal of Negro Education, 87(4), 391-403. doi: 10.7709/jnegroeducation.87.4.0391 [ Links ]

Cyrulies, E. & Schamne, M. (2021). El aprendizaje basado en proyectos: una capacitación docente vinculante. Páginas De Educación, 14(1), 1-25. doi: 10.22235/pe.v14i1.2293 [ Links ]

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A.L. (2015). Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Fourth Edition. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications, Inc. [ Links ]

Coughlin, C. (2015). Developmental Coaching to Support the Transition to Self-Authorship. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 148, 17-25. doi: 10.1002/ace.20148. [ Links ]

Creamer, E. G., & Laughlin, A. (2005). Self-Authorship and Women’s Career Decision Making. Journal of College Student Development , 46(1), 13-27. doi: 10.1353/csd.2005.0002. [ Links ]

Day, D.A., & Lane, T. (2014). Reconstructing faculty roles to align with self-authorship development: The gentle art of stepping back. The Canadian Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 5(1), doi: 10.5206/cjsotl-rcacea.2014.1.5 [ Links ]

Del Prato, D. (2017). Transforming Nursing Education: Fostering Student Development towards Self-Authorship. International Journal of Nursing Education Scholarship, 14(1). doi: 10.1515/ijnes-2017-0004 [ Links ]

Delval, J. (2014). El desarrollo humano. Decimosexta reimpresión. Madrid: Siglo Veintiuno Editores. [ Links ]

Flores, R. C., Otero, A., & Lavalleé, M. (2010). La evolución de la perspectiva epistemológica en estudiantes de posgrado: El caso de los psicólogos escolares. Perfiles Educativos, 32(130), 8-24. doi: 10.22201/iisue.24486167e.2010.130.20570 [ Links ]

González-Ferriz, F. (2021). Aprendizaje Basado en Proyectos en Formación Profesional: la aplicación de las nuevas tecnologías a la investigación de mercados en los ciclos de comercio y marketing. ENSAYOS, Revista de la Facultad de Educación de Albacete, 36(1). doi: 10.18239/ensayos.v36i1.2653 [ Links ]

Johnson, J. L., & Chauvin, S. (2016). Professional Identity Formation in an Advanced Pharmacy Practice Experience Emphasizing Self-Authorship. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 80(10), 1-11. doi: 10.5688/ajpe8010172 [ Links ]

Kenner, K. A. (2019). A Community College Intervention Program: The Affordances and Challenges of an Educational Space of Resistance. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education . Advance online publication. doi: 10.1037/dhe0000116. [ Links ]

King, P. M., & Baxter, M. B. (2004). Creating learning partnerships in higher education: Modeling the shape, shaping the model. In M. B. Baxter & P. M. King (Eds.), Learning partnerships: Theory and models of practice to educate for self-authorship (pp. 303-332). Stirling, VA: Stylus. [ Links ]

Laughlin, A., & Creamer, E. G. (2007). Engaging Differences: Self-Authorship and the Decision-Making Process. New Directions for teaching and learning, 109, 43-51. doi: 10.1002/tl.264 [ Links ]

Lewis, P., Forsythe, G. B., Sweeney, P., Bartone, P., Bullis, C., & Snook, S. (2005). Identity Development during the College Years: Findings from the West Point Longitudinal Study. Journal of College Student Development , 46(4), 357-373. doi: 10.1353/csd.2005.0037 [ Links ]

McGowan, A. L. (2016). Impact of One-Semester Outdoor Education Programs on Adolescent Perceptions of Self-Authorship. Journal of Experiential Education, 39(4), 386-411. doi: 10.1177/1053825916668902 [ Links ]

Myers, L. W. (2017). Exploring Self-Authorship in Post-Traditional Students: A Narrative Study in Students’ Meaning-Making. (PhD dissertation). College of Graduate and Professional Studies at the University of New England, USA. All thesis and dissertations. 119. http://dune.une.edu/theses/119 [ Links ]

Mondisa, J.-L., & Adams, R. S. (2020). A learning partnerships perspective of how mentors help protégés develop self-authorship. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education . doi: 10.1037/dhe0000291 [ Links ]

Mozas-Calvache, A. T., & Barba-Colmenero, F. (2013). System for Evaluating Groups When Applying Project-Based Learning to Surveying Engineering Education. Journal of Professional Issues in Engineering Education and Practice, 139 (4), 317-324. doi: 10.1061/(ASCE)EI.1943-5541.0000160 [ Links ]

Orozco, R. C., & Perez-Felkner, L. (2018). Ni de Aquí, Ni de Allá: Conceptualizing the self-authorship experience of gay Latino college men using conocimiento. Journal of Latinos & Education, 17(4), 386-394. doi: 10.1080/15348431.2017.1371018 [ Links ]

Reybold, L. E. (2002). Pragmatic epistemology: ways of knowing as ways of being. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 21 (6), 537-550. doi: 10.1080/0260137022000016776 [ Links ]

Ricks, M., Meerts-Brandsma, L., & Sibthorp, J. (2021). Experiential Education and Self-Authorship: An Examination of Students Enrolled in Immersion High Schools. Journal of Experiential Education , 44(1), 65-83. doi: 10.1177/1053825920980787 [ Links ]

Rodríguez-Sandoval, E., Vargas-Solano, E. M., & Luna-Cortés, J. (2010). Evaluación de la estrategia “aprendizaje basado en proyectos”. Educación y Educadores, 13 (1), pp. 13-25. http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/eded/v13n1/v13n1a02.pdf [ Links ]

Ruiz, J. I. (2009). Metodología de la investigación cualitativa. 5 ed. Bilbao: Universidad de Deusto. [ Links ]

Salido, P. V. (2020). Metodologías activas en la formación inicial de docentes: Aprendizaje Basado en Proyectos (ABP) y educación artística. Revista de Currículum y Formación de Profesorado, 24(2), 120-143. doi: 10.30827/profesorado.v24i2.13656 [ Links ]

Sandars, J., & Jackson, B. (2015). Self-authorship theory and medical education: AMEE Guide No. 98, Medical Teacher, 37(6), 521-532. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2015.1013928 [ Links ]

Sandín, M. P. (2003). Investigación cualitativa en educación: fundamentos y tradiciones. Mc Graw and Hill. [ Links ]

Williams, J. G. (2016). Assessing Self-Authorship among Athletic Training Students. Theses and Dissertations. 64, 1, 2016. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd/641 [ Links ]

Zaytoun, K. (2005). Identity and learning: the inextricable link. About campus, 9 (6), 8-15. doi: 10.1002/abc.112 [ Links ]

Notes

7All participants signed an Informed Consent form describing the objectives of the research and authorizing the use of the information for scientific purposes

Received: January 19, 2022; Accepted: August 15, 2022; pub: August 31, 2022

texto en

texto en