Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Revista de la Facultad de Medicina Humana

Print version ISSN 1814-5469On-line version ISSN 2308-0531

Rev. Fac. Med. Hum. vol.20 no.1 Lima Jan./Mar. 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.25176/rfmh.v20i1.2280

Review article

Radiological semiology in emergency brain pathology

1Tomography and resonance service, Edgardo Rebagliati Martins National Hospital, EsSalud. Lima, Peru.

2Center of excellence for diagnostic imaging of Clínica Internacional - San Borja Headquarters. Lima, Peru.

3Radiology area of the professional school of medical technology - Faculty of Medicine - Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos. Lima, Peru.

4Polyclinic ANCIJE - Almenara Deconcentrated Network - EsSalud. Lima, Peru.

Radiology is a great tool in the diagnosis of encephalic pathologies, especially in situations of neurological urgency and emergency, to rule out the presence of a specific pathology, and to definite the location and size of the lesion, or clarify an initial uncertain diagnosis. In this way, the knowledge of its main signs, findings and characteristics is important to perform an adequate examination, because it facilitates the description of the images obtained with greater speed and precision allowing an optimal and immediate labor of the treating doctor in favor of the patient. Therefore, this article presents a brief review of the representative radiological semiology obtained in the medical literature, where the references were bibliographies and researches, which is convenient to localize the signs that could exist as soon as the examination was obtained, for the future therapeutic of the patient, such as the possibility of extension in the radiology exam or suggestion by the medical technologist of radiology in coordination with the requesting physician to guarantee the patient's care effective.

Key words: technology; Emergencies; Brain diseases; Traumatic brain injuries; Stroke. (source: MeSH NLM)

INTRODUCTION

Radiology has made it possible to constitute a great support tool in the diagnosis of cranioencephalic pathologies in patients admitted as emergencies in situations that require immediate attention, such as headache, vertigo, syncope, coma, and epileptic crises. The requested radiological exams allow to confirm or to discard the presence of a specific pathology, and to see the location and extension of a lesion, or to clarify the fact of not having defined an accurate initial diagnosis1,2.

From the neurological urgency and emergency cases mentioned before, there are different diseases that cause these cases. We specifically refer to certain pathologies, which are seen in emergency and are responsible for the situations mentioned before, and which according to the classification of brain pathology comprises two types: cranioencephalic trauma and cerebrovascular diseases2,3,4.

Once the pathologies are defined, it is necessary to take into account their representative radiological signs, which can be found scattered in bibliographies, hemerographies and cyberspace. In this sense, the knowledge of the main signs, findings and characteristics is important because it allows to consider a proper performance of the examination, as well as to facilitate the description of the images obtained with greater speed and precision, thus contributing to the optimal and immediate management of the treating physician in favor of the patient1,5,6.

It should be noted that the main radiological technologies used for this assessment are: Radiodiagnosis which is rarely used today, computed tomography in most situations, and magnetic resonance imaging for specific cases, which will be performed without application of intravenous contrast substance because its use is not required in this instance, without ruling out its use in case it is necessary to immediately extend the test to the moment after the first examination performed5,6,7.

A summary of the most representative radiological signs of brain imaging given in emergency is presented, as a contribution to the location of the sign that could exist as soon as the examination was obtained, as well as to define the therapeutic management to be provided by the medical and nursing staff, and the possibility of any immediate extension or suggestion of the examination carried out by the medical radiology technologist staff in coordination with the requesting physician to take care of the patient effectively.

REVIEW OF THE MAIN RADIOLOGICAL SIGNS

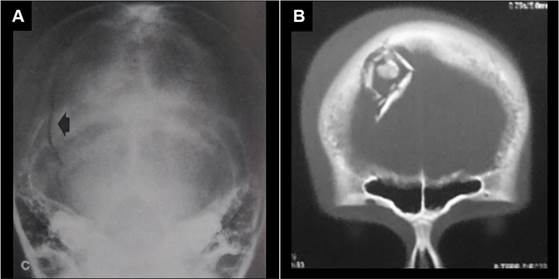

Radiographic sign of dissolution of bony continuity

This sign seen by a plain X-ray skull (SXR) constitutes defined traces or lines at the level of the bone structure, which are denoted black (radiolucent) in relation to the surrounding bone tissue which is denoted white (radiopaque). The bone continuity solutions correspond to fractures, and preferably they will have a linear arrangement, although other morphological types will be fractures due to subsiding, de-escalation, or in mosaic (Figure 1). It should be noted that fractures can be classified according to anatomical type into two groups: those of the vault and those of the base of the skull, being the fractures of the base those of the difficult visualization in conventional radiography(8,9,10,11).

It is worth mentioning that the definition of this sign by a radiographic image allows to rule out its presence in the patient, due to its high specificity and high negative predictive value (approx. 94.9% and 83.1% respectively), in other words, it has a high probability of finding a true positive, although certain reservations must be taken (condition and age of the patient). Therefore, the X-ray should be used only to corroborate the clinical suspicion that may previously exist in a patient with normal clinical examination. Thus, in other situations the obtaining of radiological signs will be done by computed tomography(8,9,10,11).

Tomography sign of bone fracture

As it was in a radiographic image, computed tomography allows us to see traces of fractures, but with the advantage of defining those that occur both at the level of the vault and at the base of the skull. Fractures are denoted as black or hypodense lines, with surrounding bone tissue denoted as white or hyperdense. All this will be visible only in the appropriate tomographic window (bone window). If it is linear fracture it will be a specific line, if it is depressed the fragments will be internally displaced (Figure 1), y en ambos habrá aumento de partes blandas subyacente. Si es por descalotamiento se extiende por las suturas craneales, y si es en mosaico tendrá trazo tanto longitudinal como transversal, casos que pueden afectar arterias superficiales o senos venosos, o hasta duramadre, con posibilidad de presentarse neumoencéfalo como una secuela8,12,13,14.

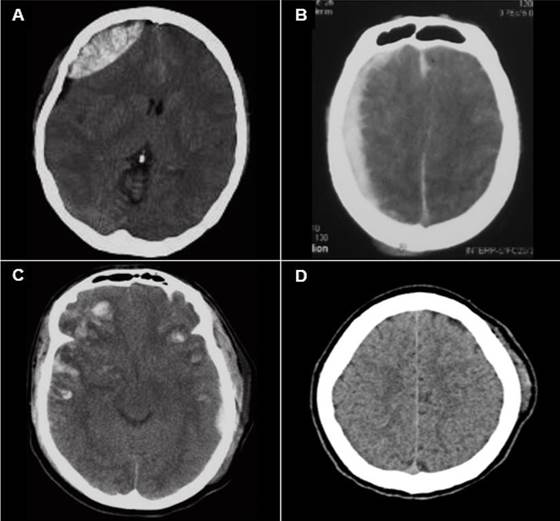

Sign of biconvex extra-axial mass

It is the classic representation of an epidural hematoma, which is located in relation to the cranial area where trauma has occurred, at the level of the underlying brain, with compressed subarachnoid space, denoting a double convexity (towards the cerebral parenchyma as well as towards the cranial vault), displacing the interface between gray and white substances.

It occurs in 85 - 90% of traumatic cases, occurring at the point of impact, and its visualization is performed preferably by computed tomography (Figure 2), ), where 2/3 of the cases are hyperdense and 1/3 are mixed (with hyper/hypo content), while in magnetic resonance imaging it will usually be isointense with the cortical bone in most sequences with a black line between hematoma and parenchyma (displaced dura mater)13,15,16,17.

Sign of semilunar extra-axial collection

It is the classic representation of a subdural hematoma, denoting a semilunar collection over the cerebral hemisphere, with points of cerebrospinal fluid in the compressed grooves and internally displaced with respect to the cranial vault, which may cross sutures, but not dural insertions. Basically visualized by computed tomography, 60% is hyperdense (Figure 2), and 40% is mixed (with hyper/hypo content) denoting active hemorrhage or torn arachnoid, especially if the hematoma has days or very few weeks of presentation. As the hematoma has a longer evolution time, from weeks to months, it may present hyperdense septa (trabecular morphology) or appear hyperdense and hypodense in the lower and higher areas of the hematoma respectively, in other words, double contents (separate morphology)13,16,18,19.

Sign of patched brain hemorrhage

It is the characteristic sign of cerebral contusions, produced from a previous cranioencephalic trauma, where the convolutions impact on the bone, being most frequently located at the anteroinferior level in the temporal lobes, in the perisilvian cortex, and at the anteroinferior level in the frontal lobes (Figure 2). It is associated in 35% of cases with cranial fractures and in 70% of cases with subgaleal hematomas, where its initial visualization is by computed tomography, which shows a hypodense cortical bone with one or multiple hyperdense lesions that represent contusions, while a magnetic resonance imaging will define in greater detail the extent of the lesion where the cortical bone will be edematous19,20,21,22.

Sign of subgaleal hematoma

It is the classic hematoma of soft tissues given from a simple blow to the head, where cellular extravasation occurs below the aponeurosis of the cranial region, which tends to remain fluctuating and liquid, and is located at the limits of its insertions, ahead to the supraorbital region, on the sides by the temporal regions and behind to the level of the nape of the neck. It can form without bone injury, or with undisplaced fractures. The hematoma that invades the loose connective tissue separates the aponeurotic galea from the periosteum and may pass through the sutures. This sign gradually becomes noticeable 12 - 72 hours after the trauma occurs, but may be noticed longer in severe cases. Its visualization is given by a cerebral tomography, with parenchymal window, where it will be observed as a hyperdensity adhered externally to the cranial vault (Figure 2)5,7,23,24.

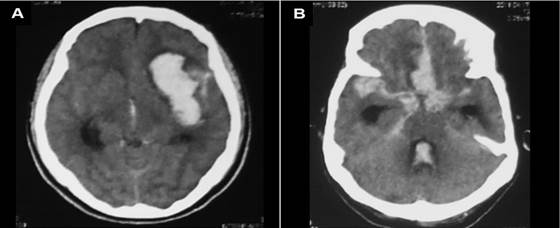

Sign of intraparenchymal hemorrhage

It is the representation of the hematic content at the level of the cerebral parenchyma in general which can be lobar or deep, and the latter in turn will be mainly at the level of the basal ganglia (if it is associated with hypertensive crises), thalamus, brainstem, and cerebellum. This hematoma will have an oval shape, with generally precise limits, with hyperdensity in its interior and perilesional edema, which if irregular will indicate poor prognosis, and in all cases with the respective mass effect, all this can be quickly visualized by a computed tomography, especially if the hemorrhage has a high blood content or is of great extension (Figure 3)20,25,26,27.

Sign of subarachnoid hemorrhage

It is the representation of the hematic content at the level of the subarachnoid spaces and their expansions around the brainstem, tentorial notch and the foramen magnum, called cerebral cisterns. This finding is observed precisely as hyperdensity of basal cisterns and convexity grooves and extending through cerebellopontine angles, choroid plexus and ventricular system (Figure 3). The acute extravasation of blood may be due to arterial leaks or venous tears. Potential causes include trauma, ruptured aneurysms, vascular malformations, and the cerebral amyloid angiopathy. If the subarachnoid hemorrhage is traumatic, it is adjacent to the contusions and there is a greater amount of hematic content in the convexity grooves than in the basal cisterns, while if the hemorrhage is aneurysmal, there will be greater content in cisterns, requiring some angiographic test to determine the lesion.20,24,25,28.

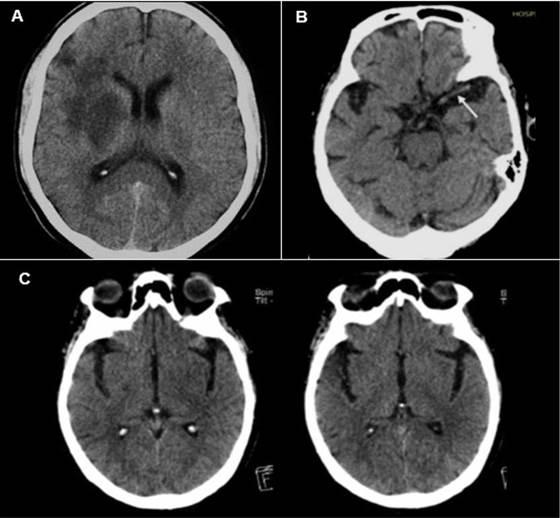

Sign of hypodensity of the lenticular nucleus

It is the representation of acute ischemia of the lenticulostriate territory, denoted by computed tomography as a darkening in its interior due to cytotoxic edema, given especially by infarctions in territory whose irrigation is given by the middle cerebral artery. When this hypodensity occurs, both the globus pallidus and the putamen are affected, although the first is affected earlier, and this can be observed in only two hours after the beginning of the the ischemic event (Figure 4).It should be noted that this representation can be observed specifically at six hours along with loss of differentiation of white and gray matter in the cerebral cortex5,29,30,31.

Sign of hyperdense middle cerebral artery

It is an early sign of cerebrovascular disease, either ischemia or hemorrhage, visible on non-contrast tomography, first described in 1981 by D.H. Yock, which corresponds to the high density at the level of the middle cerebral artery in comparison with the contralateral artery, its most frequent location being the first segment, given by the occlusion of an embolus or thrombus, where its radiological density will be greater than the circulating blood (80 and 40 Hounsfield Units respectively) due to the greater amount of protein and fibrin, with a lower proportion of serum (Figure 4). Although this sign has high specificity, almost 100%, its sensitivity is relatively low, approx. 30%, being occasionally a false positive sign, especially when it presents bilaterally and in patients who additionally have calcification of arteries or high hematocrits, as well as patients without symptomatology with dehydration or polyglobulia. In addition, the appearance of this vessel may be hyperdense in patients with vascular calcifications or arteriosclerotic disease5,25,29,30.

Sign of the cortical or insular ribbon

It is the sign of hypodensity of the cortex at the edge of the insular lobe, which leads to a loss of distinction between insular cortex and outer/extreme capsule, with loss of differentiation between white and gray matter (Figure 4). This sign will occur because a cytotoxic edema given at the level of the insular cortex is susceptible to early and irreversible changes of the ischemic cerebrovascular event, especially because it is part of the territory irrigated by the middle cerebral artery, whose capacity is less to supply the circulation through collateral vessels from the anterior and posterior cerebral arteries5,29,30,31.

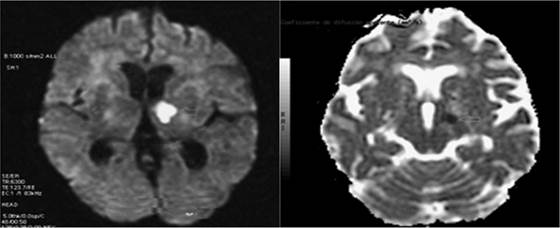

Sign of restricted diffusion or early ischemia

It is the classic representation of intracellular cytotoxic edema given by magnetic resonance imaging a situation where the mobility of water is restricted and that occurs mainly in cerebral ischemia, and whose early detection in this test is done in a short time by the diffusion sequence. This sequence, which is echo-planar, detects the random or Brownian motion of water molecules in different directions of the magnetic field gradient, which if restricted as in ischemia, will be detectable quickly2,4,32,33.

This will be helpful when the computed tomography does not provide any signs despite existing clinical signs, where this sequence will detect very early changes between 30 minutes and 6 hours, assessing both the diffusion image and its ADC map that shows contrast purely based on diffusion differences without consideration of contrast T2, in other words, at the level of the area where cytotoxic edema occurs, it will be denoted with a bright white color (hyperintense), and its ADC map will detect the same, but it will be denoted black (hypointense), a situation that is not differentiable in a T1 sequence (Figure 5)2,4,32,33.

CONCLUSIONS

Reviewing information obtained in some research as a reference bibliography, it is concluded that by means of diagnostic imaging it is possible to define signs, findings and radiological characteristics that clearly denote the existence of any pathology at the cranioencephalic level that has been the cause of some neurological emergency or urgency, which will therefore be pathognomonic. In this way, the knowledge of radiological semiology will allow to quickly describe if they exist both for the therapeutic management and for the immediate expansion or suggestion by the radiology medical technologist staff in coordination with the requesting physician, making effective the care provided to the patient who has been admitted due to emergency.

REFERENCES

1. Jiménez L, Montero J. Medicina de urgencias y emergencias: Guía diagnóstica y protocolos de actuación. 5a ed. Barcelona: Elsevier; 2015. [ Links ]

2. Borruel M, Martínez A, Estabén V., Morte A. Manual de Urgencias Neurológicas. Teruel: Servicio de Urgencias del Hospital Obispo Polanco; 2013. [ Links ]

3. Mercado T. Correlación clínicotomográfica en la evolución del Trauma Craneoencefálico en el Hospital Antonio Lenin Fonseca, octubre 2016. Tesis de Especialidad. Managua, Nicaragua. Facultad de Ciencias Médicas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Nicaragua; 2017. 73 pp. [ Links ]

4. Zarranz J. Neurología. 6a ed. Barcelona: Elsevier; 2018. [ Links ]

5. Del Cura J, Pedraza S, Gayete A. Radiología esencial. 2a ed. Madrid: Editorial Médica Panamericana; 2018. [ Links ]

6. Lobo E. Manual de Urgencias Quirúrgicas. 5a ed. Madrid: Imprenta Pedragosa; 2016. [ Links ]

7. Román A. Características epidemiológicas y patologías halladas por tomografía computada cerebral en adultos atendidos en emergencia. Tesis. Lima, Perú. Facultad de Medicina, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos; 2012. 91 pp. [ Links ]

8. Pope T, Harris J. Radiología en Emergencias Médicas Harris & Harris. 5a ed. Medellín: Editorial Amolca; 2014. [ Links ]

9. Onofre J, Mancilla A. Utilidad actual de la radiografía simple en el diagnóstico de fracturas de cráneo. An Rad Mex. 2010; 2(1): 73-75. [ Links ]

10. Ortega E. Técnica radiológica para pacientes con Traumatismo Craneoencefálico con Uso de Rayos X. Tesis. Loja, Ecuador. Área de la Salud Humana, Universidad Nacional de Loja; 2013. 45 pp. [ Links ]

11. Torre J. Diagnóstico por imágenes en pacientes con Traumatismo encefalocraneano en el Tópico de Emergencia de Cirugía del Hospital Carlos Lanfranco La Hoz de Julio 2016 - Noviembre 2016. Tesis. Lima, Perú. Facultad de Ciencias de la Salud, Universidad Privada San Juan Bautista; 2017. 52 pp. [ Links ]

12. Avilés C, Ayala J, Bermeo J. Hallazgos tomográficos en pacientes con traumatismo craneoencefálico. Departamento de Imagenología. Hospital Vicente Corral Moscoso. Cuenca, julio - diciembre 2012. Tesis. Cuenca, Ecuador. Facultad de Ciencias Médicas, Universidad de Cuenca; 2013. 74 pp. [ Links ]

13. Osborn A. El Encéfalo: Diagnóstico por imagen, patología y anatomía. Madrid: Editorial Médica Panamericana; 2018. [ Links ]

14. Varela A, Martínez C, Muñoz R, Torres R, Orellana F, Lamus L, Herrera P. Algoritmo para la tomografía secuencial de cráneo en pacientes con traumatismo encéfalocraneano. Rev Chil Neurocirugía. 2016; 42(1): 24-30. [ Links ]

15. Belduma V. Traumatismo craneoencefálico: Diferencias tomográficas entre el hematoma epidural y subdural para el diagnóstico precoz de sus complicaciones. Tesis. Machala, Ecuador. Unidad Académica de Ciencias Químicas y de la Salud, Universidad de Machala; 2019. 23 pp. [ Links ]

16. Morales H. Utilidad de la Tomografía axial computarizada para la detección de hematomas epidurales y subdurales en pacientes de 40 a 60 años de edad en el Hospital "Enrique Garcés" en el periodo de agosto 2015 a diciembre 2015. Tesis. Quito, Ecuador. Facultad de Ciencias Médicas, Universidad Central del Ecuador; 2016. 79 pp. [ Links ]

17. Rodríguez M, Dosouto V, Rosales Y, Musle M, González Y. Valor de la tomografía axial computarizada para el diagnóstico precoz del traumatismo craneoencefálico. MEDISAN. 2010; 14(6): 767-773. [ Links ]

18. Guamán V. Utilidad de la Tomografía Simple de Cráneo para la Detección del Hematoma Subdural Crónico en pacientes de 40 A 60 años que acuden al servicio de Imagen del Hospital de Especialidades Eugenio Espejo de la ciudad de Quito en el periodo Julio a Diciembre del 2015. Tesis. Quito, Ecuador. Facultad de Ciencias Médicas, Universidad Central del Ecuador; 2016. 113 pp. [ Links ]

19. Remón C, Pernía L, Corrales N, Castañeda C. Tomografía axial computarizada en traumatismos encefalocraneanos. Experiencia en 6 años: Enero 2006-Diciembre 2012. Multimed. 2013; 17(2): 64-80 [ Links ]

20. Osborn A. Cerebro. Serie Diagnóstico por Imagen. 2a ed. Madrid: Marbán; 2011. [ Links ]

21. Sierra E, León M, Rodríguez E, Pérez L. Caracterización clínico-quirúrgico, neuroimagenológico y por neuromonitorización del trauma craneoencefálico en la Provincia Matanzas 2016-2018. Rev Med Electron. 2019; 41(2): 368-381 [ Links ]

22. Tandazo D. Determinación imagenológica de la lesión cerebral mediante tomografía axial computarizada en pacientes con trauma craneoencefálico ingresados en el Hospital Isidro Ayora. Tesis. Loja, Ecuador. Área de la Salud Humana, Universidad Nacional de Loja; 2014. 95 pp. [ Links ]

23. Cuya C. Traumatismo encefalocraneano mediante tomografía axial computarizada en pacientes atendidos en el Centro Médico Naval Cirujano Mayor Santiago Távara periodo julio 2013-2015. Tesis. Lima, Perú. Facultad de Medicina Humana y de Ciencias de la Salud, Universidad Alas Peruanas; 2016. 42 pp. [ Links ]

24. Fernández F, Timbe C. Incidencia de lesiones causadas por traumatismo cráneo encefálico diagnosticadas por tomografía en pacientes del Hospital Homero Castanier Crespo de Azogues, período enero - diciembre del 2017. Tesis. Cuenca, Ecuador. Facultad de Ciencias Médicas, Universidad de Cuenca; 2019. 84 pp. [ Links ]

25. González R, Garbey B, Valdés O. El ABC del accidente cerebro vascular en la tomografía computarizada de cráneo. Rev Cub Med Intensiva y Emergencias. 2018; 17(1):19-35. [ Links ]

26. Hernández A, Aladrén J, Tejada H, Cruz G, Angel L, Seral P, Artal J, Marta J. Signos predictores de crecimiento precoz de la hemorragia intracerebral en la tomografía computarizada sin contraste y mortalidad. Rev Neurología. 2018; 67(7): 242-248. [ Links ]

27. Rodríguez S, Domínguez E, Bolaños S. Tomografía axial computarizada en las enfermedades cerebrovasculares hemorrágicas. Panorama Cuba y Salud. 2011; 6(1): 139-141. [ Links ]

28. Reyes Y. Tomografía computarizada y el diagnostico de patología cerebrovascular hemorrágica. Tesis. Guayaquil, Ecuador. Facultad de Ciencias Médicas, Universidad de Guayaquil; 2012. 106 pp. [ Links ]

29. de Alba J, Guerrero G. Evento vascular cerebral isquémico: hallazgos tomográficos en el Hospital General de México. An Rad Mex. 2011; 3(1): 161-166. [ Links ]

30. Blanco M, Arias S, Castillo J. Diagnóstico del Accidente Cerebrovascular Isquémico. Medicine. 2011; 10(72): 4919-4923. [ Links ]

31. Herrera A. Signos radiológicos presentes en tomografía computada simple en pacientes con accidente cerebrovascular isquémico. Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Neurológicas, Octubre a Diciembre del 2017. Tesis. Lima, Perú. Facultad de Medicina, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos; 2018. 103 pp. [ Links ]

32. Pitot L. Comparación de imágenes entre secuencia convencional y secuencia de difusión en la resonancia magnética nuclear del accidente cerebrovascular isquémico agudo. Centro Diagnóstico Osteoperú, Lima-2017. Tesis. Lima, Perú. Facultad de Medicina, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos; 2018. 84 pp. [ Links ]

33. Reyes I, Rivas C, Robles C. Tomografía Tomografía Axial Computarizada vs. Resonancia Magnética como método de estudio de la Enfermedad Cerebro Vascular Isquémica Aguda. Naguanagua, Estado Carabobo, Año 2013. Tesis. Carabobo, Venezuela. Facultad de Ciencias de la Salud, Universidad de Carabobo; 2013. 25 pp. [ Links ]

Received: October 22, 2019; Accepted: November 26, 2019

text in

text in