INTRODUCCIÓN

The existing literature indicates that college students between ages 18 to 24 years old were more likely to engage in risky sexual behaviors such as having multiple sexual partners,1,2,3,4,5,6 engaging in sex while under the influence of alcohol and drugs3,7,8 and ignoring protective measures such as contraception against Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs) and unplanned pregnancy6,9,10 . In fact, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) National Survey of Family Growth estimated that over the last three decades, there has been an increase in the number of teenagers engaging in sexual practices with the median age of first sexual encounter being 17.8 years old11. The Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance (YRBS) reported that in 2013, 3.9% of students had sexual intercourse before age 136 . Although studies have shown that college students are sexually active1,3 and are utilizing contraception methods, limited research focuses on the sexual health needs of the Hmong community. Hmong was an agrarian ethnic minority group from the high mountains of Laos. After the Vietnam War, the Hmong immigrated to Thailand and later, resettled in the US.

The primary purpose of this research is to understand contraceptive attitudes among Hmong college students. Despite the growing Hmong population in the United States (260,000 with a median age of 20.4 (American Community Survey 2008-2010) according to the US Census Bureau), current knowledge about the contraceptive practices, perceptions, and attitudes of this population is limited and largely unexplored. Although a few studies do exist12,13 , further research is needed to investigate the contraceptive practices, barriers, attitudes, and needs in the Hmong community.

Contraceptive Attitudes among College Students

According to the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG), the number of women between the ages of 15-44 years utilizing contraceptive services such as birth control has increased from 56% in 1982, to 60% in 1988, to 64% in 1995 and to 70% from 2006-201014,15 and similar results were reported in 2011. 16 However, Kosh (2008) found results, indicating that unintended pregnancy was highest among sexually active women who are non-contraceptive users9,15,17. These studies also reported that low-income, or cohabiting women between 18-24 years old are more likely to experience unintended pregnancy,9,15,17. Additionally, a study indicated that low-income and minority women are more likely to not use contraception and are most likely to report unintended pregnancy17.

Research suggests that sexually active women who do not wish to become pregnant nor contract STIs while engaging in vaginal sexual intercourse should use some method of contraception, especially dual contraceptive methods such as condoms and oral contraception11,2,19. Failure to consistently use recommended contraceptives results in unintended pregnancies among women of reproductive age17.

Need for Contraceptive Research among Hmong College Students

Studies focusing on reproductive issues, including contraceptive use, focus primarily on Whites, Hispanics, and Blacks and seldom include members of other underrepresented groups. As a result, the Guttmatcher Institute and the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation have called for more reproductive research within different racial and ethnic minority groups in the United States. This is particularly important for the Hmong who, despite their increasing numbers, continue to be absent from research studies12.

Among the existing research, Minkler, Korenbrot, and Brindis (1988) and Kornosky et al. (2007) found Hmong participants to have a low education level, low contraceptive awareness and low utilization of contraceptive methods compared to their Southeast Asian counterparts. Hmong participants also preferred the highest number of desired of children, and had the lowest contraceptive awareness13.

A study found that only 28.4% of Hmong participants reported using a contraception method compared to 73% of the US general population12. Thusly, researchers stress the importance of understanding the Hmong community’s reproductive practices and experiences in order to better comprehend their reproductive needs and provide optimal health care delivery to the Hmong community in the United States.

Subjects and Sampling Procedures

In this study, the target population was Hmong college students between the ages of 18 to 45 attending a midsize (approximately 24,000 students as of fall 2015) institution in Central California. The sampling was based on a 95% confidence interval with a 3% - 5% margin of error. This mid-size university population consists of 12.6% self-identified Asian students, 46% Hispanics and 22% Whites. Among those identified as Asian, 46.1% further identified as Hmong.

The survey was administered online using Qualtrics, a web-based instrument, with the assistance of the Office of Institutional Effectiveness (OIE) at the University. Students were randomly selected to participate in the survey. A total of 700 invitations, representing 48.5% of the Hmong population, were sent to Hmong students age 18 and older. Two additional email messages were sent to participants as reminders to take the survey.

Survey results were compiled by the OIE, which also provided demographic information for the student participants. To maintain confidentiality and anonymity, no personal identifying information was made available to the researchers.

METHODS

The study was implemented using an electronic version of the Contraceptive Attitude Scale (CAS) developed by Dr. Kelly Black. The CAS is a 32-item scale measuring general contraceptive attitudes with 17 positively and 15 negatively phrased items to which respondents indicate their level agreement or disagreement. For data analysis, negatively worded questions were reversed so that all questions were positively scored. The scale has a statistically significant test-retest reliability (p< 0.001). Participants were asked a series of demographic questions as well as inquiries regarding their sexual activity. Participants who indicated to have not ever had sexual intercourse were exempt from the sexual activity questions and skipped to the CAS instrument.

Two multiple regression models were generated to compare the association between critical demographic characteristics and the CAS scores - the first multiple regression test controlled for variables including gender, marital status, cohabitation, years in the US, years in college, Hmong/English spoken at home, religion, birthplace and desired number of children. The second multiple regression test included sexual activity as a control variable. The variables were dummy-coded to 1 (indicating a “yes” response) and 0 (indicating a “no” response).

RESULTS

Demographic

A total of 344 of 700 students successfully completed the survey, with a 49% return rate. Among the participants, 253 identified as female and 91 identified as male. All were between the ages of 19 to 33 years old. Most of the participants were born in the United States (83%) compared to 17% born elsewhere (Thailand, Laos and Other). The vast majority (96%) indicated living in the United States for more than 10 years and 60% reported speaking Hmong as their primary language at home. The years of education of participants was more evenly split with 55% having spent less than five years in college compared to 43% over 5 years in college. Over half of the participants (60%) identified shamanism1 as their primary religion (Table 1).

Table 1 Characteristics of Hmong college students’ contraceptive attitudes analysis (n=344).

| Characteristic | (%) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 253 (74%) |

| Male | 91 (26%) |

| Age | |

| <25 years | 305 (89%) |

| >25 years | 39 (11%) |

| Years in college | |

| <5 years | 189 (55%) |

| 5-10 years | 147 (43%) |

| 10+ years | 8 (2%) |

| Religion | |

| Shamanism | 206 (60%) |

| Others | 138 (40%) |

| Primary language at home | |

| Hmong | 206 (60%) |

| English | 117 (34%) |

| Others | 21 (6%) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 279 (81%) |

| Married | 46 (13%) |

| Partnered (cohabitating), but not married | 13 (4%) |

| Other | 6 (2%) |

| No. Desired Children | |

| 0 | 15 (4%) |

| 2 | 13 (4%) |

| 3 | 70 (21%) |

| 4 | 116 (35%) |

| 5+ | 34 (10%) |

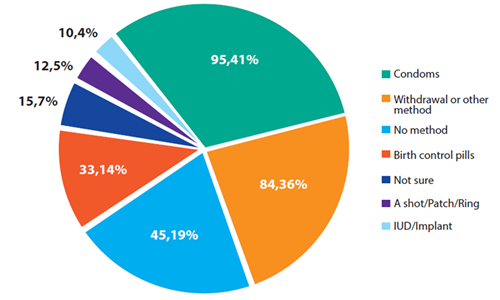

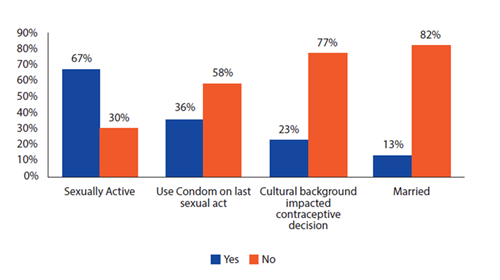

Regarding marital status, 81% were single compared to 13% who are married and 4% cohabitating (Table 1). Sixty-seven percent reported having previously had sexual intercourse (Figure 2), and 62% had at least one sexual partner within the past 12 months. Of the participants who have had sexual intercourse, only 36% reported using condoms during their most recent sexual interaction (Figure 2). Using a condom (41%) was in fact the most reported contraceptive method used during the last sexual encounter, followed by withdrawal (36%) and then no birth control method to prevent pregnancy (19%) (Figure 1). Lastly, 78% reported that their decision regarding contraceptive use had not been affected by their cultural background (Figure 2).

Multiple Comparison: Regression Models

A simple additive scale was created using 32 statements that asked participants to self-report about contraceptive use and attitudes. The scale ranged from 32 to 180, with higher scores denoting more positive views of contraception. The distribution is slightly skewed to the left with a few individuals serving as outliers on the lower end of the scale. On average, participants tend to have a more positive view of contraception with a score of 118.10 and a standard deviation of 15.94.

Two multiple regression models analyzing CAS scores using demographic characteristics were generated (Table 2). Gender was statistically significant (p< 0.001) and Hmong college women (122.08) were more likely to have positive attitudes toward contraception as compared to men (112.58).

Table 2: Contraceptive attitude multiple regression models (Contraceptive Attitude Scale (CAS) Results).

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 |

| Gender | 0.001*** | 0.001*** |

| Single | 0.092 | 0.072 |

| Married | 0.085 | 0.121 |

| Cohabitating | 0.011** | 0.017** |

| 5-10 Years in the US | 0.046* | 0.076 |

| College 5-10 Years | 0.031* | 0.144 |

| College 10+ Years | 0.682 | 0.460 |

| Hmong at Home | 0.233 | 0.303 |

| English at Home | 0.386 | 0.370 |

| Religion | 0.356 | 0.370 |

| Birthplace | 0.755 | 0.549 |

| Desire for Kids | 0.002** | 0.001*** |

| Sexually Active | 0.001*** | |

| Constant | 0.000*** | 0.001*** |

| R2 | 0.2023 | 0.2443 |

| N | 309 | 309 |

* Significant at p<.05 level ** Significant at p<.01 level *** Significant at p<.001 level

There is a clear difference in contraception attitudes between participants who have a strong desire to have children from those who do not have a desire to have children. Desire for children is a statistically significant variable (p< 0.002) with participants who reported to have a strong desire for more children, having a less positive attitude towards contraception (p< 0.0001). The three most popular choices for desired number of children are 3 (15%), 2 (21%) and 4 (35%). Zero children was the next popular choice at 10%, which is equivalent to more than 4 children, also at 10%.

Years of college education also contributes to a more positive view of contraception; however, years of college education is only statistically significant from five through ten years of college (p=0.046). From zero to five years of college, college is not statistically significant. More than ten years of college is omitted because it only represented 3% of study participants.

The first multiple regression model indicates that language spoken at home, birthplace, and religion are not statistically significant across the other demographic variables (Table 2). In a previous survey question, the majority of participants responded that cultural background did not play a role in contraception decision making.

While marital status is not statistically significant (Table 2), cohabitation is statistically significant (sig. 0.01). However, cohabitation only accounts for 4% of participants and it is unclear whether they are engaged or partnered.

In the second multiple regression model, sexual activity is included as another variable. In this model, participants who are sexually active have a more positive attitude towards contraception (p < 0.000) as opposed to those who are not sexually active. Of the 344 participants who completed the survey, 67% of the participants reported to be sexually active.

Similar to the first model, participants who reported cohabitating with a partner but were not married were more likely to have a positive attitude toward contraception (p= 0.017) (Table 2). Marital status was insignificant statistically.

The relationship between the number of desired children and the gender of the participant continues to be statistically significant (p=0.001). However, the number of years in the US, and the number of years in college are not statistically significant in this model. Therefore, only sexual activity, cohabitation, desire for children, and gender remained statistically significant in this multiple regression model.

DISCUSSION

The data indicates that unmarried (85%) Hmong college students are sexually active (67%), with 62% having at least one sexual partner over the past 12 months. Using condoms is the most popular contraceptive method at 41%, followed by withdrawal at 36 %, no method of contraception at 19%, and birth control pills at 14%. Nationally, condoms are the most common contraceptive methods among college students, followed by birth control pills, and withdrawal (Mosher & Jones, 2010). According to Mosher and Jones (2010), from 2006-2008, about 93% of sexually active females in the US reported using condoms, followed by 82% using an oral contraceptive pill, and 59% using withdrawal. Contraception utilization among female Hmong college students is significantly lower, especially for more demanding contraceptive methods such as birth control pills. Despite the low contraception utilization, the average CAS score of the participants in this study is positive at 118.10 with a standard deviation of 15.94. However, only 36% of participants report having used a condom during their most recent sexual intercourse, indicating that although there is a positive view of contraception, and condoms are the preferred contraception method, contraception utilization is still low.

Inaccessibility and barriers to contraception may explain the contradiction of low contraception utilization in tandem with positive contraceptive attitude scale score. Social and physical barriers can also reduce condom utilization. For example, the perception that sexual partners carrying condoms are “risky” or diseased, or fear of not reaching sexual climax, may reduce condom use19. Future studies should explore the variables that contribute to this contradiction. Reproductive health programs addressing contraception utilization in the Hmong college student population should provide resources with appropriate access to contraception. Contraception utilization, including dual contraception, should continue to be promoted as contraception usage is low across the board (Table 2).

In most western societies, having a small family size is ideal; in the United States, the ideal family size is two children, and there was a significant decline in individuals desiring four or more children from 1970-200220. In contrast to this, contraception utilization is much lower, and the number of desired children among Hmong college students is much higher. Participants in our study reported having a much larger ideal family size: 35% reported the ideal number of children to be four while 10% reported 5 or more children to be ideal (See appendix). Desire for children was also statistically significant in both multiple regression models, denoting that a stronger desire for children results in a more negative attitude towards contraception. This finding is supported by previous research13.

Results from this study reveals that women have a more positive attitude towards contraception. This aligns with previous research in which the CAS instrument utilized on medical students found female students to have a more positive CAS score21. However, the afformentioned study also found that gender was not statistically significant. Gender was statistically significant in both multiple regression models presented in this study. Female participants accounted for 74% of the participants; this may explain the positive average CAS score in this study. The statistical significance of gender found in this study should be explored in future studies in order to explain the higher CAS score of Hmong college women as compared to men.

Five to ten years of college education was also statistically significant in the first model. Kajic (2015) found that medical education is also statistically significant and correlates with a positive CAS score. However, years of education became insignificant in the second regression model which additionally controlled for a sexual activity variable. This relationship could potentially indicate that the effect of education is influenced by sexual activity.

Acculturation was also important to consider when analyzing the contraception attitude of diverse ethnic groups since acculturation influences self-identity and attitudes22. Language spoken at home and years in the United States are two variables associated with levels of acculturation23 and were observed to look for relationship with contraception attitudes. However, both variables were not statistically significant in the two multiple regression models. Furthermore, the vast majority of participants also indicated that cultural background does not affect their contraceptive choices. As such, acculturation has minimal effect on the contraception attitude of the participants. This finding is supported by earlier research which compared race, age, and religion with the contraception attitude scale scores of male students, indicating an insignificant relationship24.

Data Limitations

While the findings presented in this study contribute to a greater understanding of contraceptive attitudes among Hmong college students, it is important to note that limitations do exist. First, data were collected through a web-based instrument. While participants were able to take the survey in the comfort and convenience of their own space and time, this allowed for a noncontrolled environment that varies from participant to participant. A second limitation may arise due to a reliance on self-reporting. The CAS questionnaire addresses sensitive topics that are personal in nature. This may introduce bias to the data because participants may not be as forthcoming in their responses, therefore calling to question the validity of the findings25. However, Randall and Fernandes (1991) suggest that computer-based survey might reduce response bias.

Small sample size is another limitation of the data. This mid-size institution reported 3,130 Asian students (14.0%), where 1,443 (6.5%) further identified as Hmong. While the survey was sent out to a total of 700 Hmong students, only 49% (344) participated, meaning only approximately 25% of the Hmong population at the institution were surveyed. In addition to the small sample size, there were also significantly fewer male student participants who completed the survey as compared to female students. It is unclear whether the survey was more appealing towards female students, or if the numbers represent the demographic of the university. As a result, the findings may be more representative of female students who accounted for 74% of the participants. Despite the limitations that exist, the study is one of the first to explore the relationship among Hmong college students and contraceptive attitudes.

CONCLUSION

Hmong college students in our samples were sexually active (67%), had a positive attitude towards contraception and have a positive CAS score (118.10 with 15.94 standard deviation). Contrary to the positive attitude towards contraception, only 36% of participants reported having utilized condoms during their last sexual intercourse. The CAS scores for Hmong college students were affected by statistically significant demographic variables from two multiple regression models, including gender, desire for children, and sexual activity. By recognizing these variables, the contraception choices and attitudes of Hmong college students can be more readily understood. Not only will understanding the contraception attitudes of Hmong college students attending this mid-size institution help design programs to target the contraception needs of these students, but it may also help to better realize the contraception needs of other Southeast Asian populations.

Public Health Implication

Finding from this study indicate that despite an educated population with a positive contraceptive attitude and little cultural influence on contraceptive choices, Hmong college students underutilize contraceptives across the board. We speculate that social barriers, including the negative stigma towards condoms and the inaccessibility of contraceptives, may help explain this low usage of contraceptives. Despite a positive contraception attitude, there is still a gap in contraceptive usage. This calls for intervention programs to render contraceptives, especially condoms, more accessible and promote their utilization as a family planning tool and a protective measure against sexually transmitted disease. As a result of the positive contraceptive attitude, it is likely that contraceptive utilization would positively increase with addition of reproductive health programs.

Moreover, gender and desire for more children are consistently shown to decrease contraceptive attitude. Educational reproductive health programs specific to the Hmong college population should have emphasis on recruiting male participants since male participants tend to have lower contraceptive attitude scores and participate in the contraceptive attitude survey at much lower frequency. It is also important to communicate to this population the importance of utilizing contraceptives as a crucial family planning tool and protective measures against sexually transmitted disease.

Notes: 1. Shamanism is not a religion. Despite there being disagreement about whether shamanism is a religion, individuals identify shamanism as a cultural practice as opposed to what religion might actually be identified in other culture. The Shaman’s role is spiritual healing and he is not worshipped as a higher entity or Deity.26