Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista de la Facultad de Medicina Humana

versión impresa ISSN 1814-5469versión On-line ISSN 2308-0531

Rev. Fac. Med. Hum. vol.21 no.2 Lima abr-jun 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.25176/rfmh.v21i1.3062

Review article

Neurological damage in SARS-CoV-2 infections

1Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas, Departamento De Microbiología. Universidad Pedro Ruíz Gallo, Lambayeque, Peru.

2Laboratorio de Inmunología - Virología. Dirección de Investigación. Hospital Regional Lambayeque, Lambayeque, Peru.

The current Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic has severely impacted the economy and health care system in more than 180 countries around the world in an unprecedented event, which since its inception has resulted in countless case reports focusing on the potentially fatal systemic and respiratory manifestations of the disease. However, the full extent of possible neurological manifestations caused by this new virus is not yet known. Understanding the interaction of SARS-CoV-2 with the nervous system is essential to assessing likely short- and long-term pathologic consequences. This review seeks to gather and discuss evidence on the occurrence of neurological manifestations and/or nervous system involvement in SARS-CoV-2 infected patients.

Keywords: Coronavirus infection; SARS-CoV-2; Central Nervous System; Brain; Neurologic Manifestations. (Source: MeSH - NLM)

INTRODUCTION

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an acute respiratory illness caused by the type 2 coronavirus which causes severe acute respiratory syndrome, abbreviated SARS-CoV-2, resulting in higher mortality in adults over 60 years of age and with previous conditions such as cardiovascular disease, chronic respiratory disease, diabetes or cancer. Reported symptoms include fever, cough, fatigue, sore throat, shortness of breath and in many cases ageusia and anosmia1. It is mainly disseminated by air via respiratory droplets, aerosols and fomites, although the latter route of transmission is unlikely according to recent research2. COVID-19 has affected approximately 80 million people around the world since it first appeared at the end of 20193and there is every reason to believe that the virus will remain endemic in certain regions of the world4.

SARS-CoV-2 is a genus of the coronavirus beta, which harbors other zoonotic viruses that relatively affect humans. It causes mainly respiratory and gastro-intestinal symptoms. However, the virus not only acutely affects the respiratory tract, but also a variety of cardiac, endocrine and neurological diseases have been described. Neurological manifestations have been reported in at least 36% of infected patients, supporting the neurotropic potential of the virus5.

The association of COVID-19 with neurological impairment is mostly observed in serious cases, in patients with comorbidities and atypical manifestations of the disease. Likewise, the clinical manifestations at the neurological level in infected patients have been robustly described and supported6. For this reason, the purpose of this survey was to determine the possible mechanisms by which SARS-CoV-2 produces the various neurologic manifestations among COVID-19 patients during the current pandemic, since identifying whether the possible damage produced by the virus is direct or indirect will have an impact not only on the diagnostic scheme but also on the therapeutic scheme, allowing early management of the disease and thus preventing the complication of the patient's condition and the spread of the virus.

METHOD

For the present review we searched theMEDLINEdatabases, accessed fromPubMed, SciELO, LILACSand preprint repositories such asbioRxiv, medRxiv and ChinaXivusing the descriptorsMedical Subject Headings(MeSH) linked to free terms:COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, coronavirus infection, COVID-19 clinical features, neurologic manifestations, central nervous system, brain, peripheral nervous system. This strategy has been adapted to databases, without restriction regarding the language of publication, until 17 December 2020. Observational studies, case-control studies, case series, case reports, letters to editors and reviews referencing neurological damage caused by COVID-19 were identified as inclusion criteria. Non-human coronavirus studies, clinical reports of neurologic manifestations with onset prior to SARS-CoV-2 infection, duplicate studies, and studies that did not provide relevant information for the investigation after reading the abstract or content were excluded.

DEVELOPMENT

Mechanisms of viral entry into the central nervous system

Viral infections that escape local control at the site of primary infection can spread to other tissues, where they cause more serious problems due to active virus replication or overreaction of the innate immune system. This latter reaction is sometimes considered a "cytokine storm" as proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines elevated in the serum cause a vigorous systemic immune response. Such a response in the brain can be devastating and lead to meningitis, encephalitis, meningoencephalitis and death7.

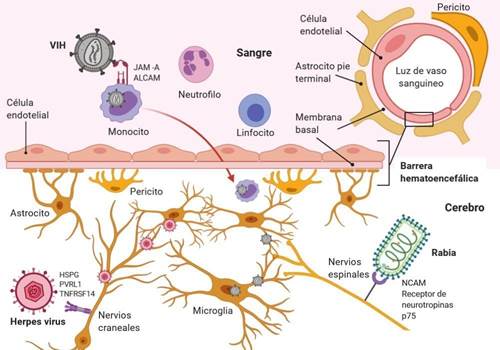

Mutations in virus-specific virulence genes, immunosuppression, age, host comorbidities, or a mix of both determine that some viruses may have access to the central nervous system (CNS) (figure 1)7. CNS, although protected by meninges and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), is not immunized against alterations that result in neurological diseases. Many viruses have the capacity to invade the CNS, where they may infect resident cells, including neurons (figure 1). Thus, there are mainly two routes of CNS invasion used by viruses, neuroinvasion via the bloodstream (hematogenous route) and via peripheral nerves (neuronal pathway).

Neuroinvasion via the bloodstream (hematogenous route)

After primary infection and once inside the bloodstream, viruses can pass the blood-brain barrier (BBB) into nervous tissue by a transendothelial mechanism, which is cellular transport across the BBB and pericytes by endocytic vesicles8. Some viruses directly infect vascular endothelial cells, enabling them to transition directly from BBB to CNS7,8. Furthermore, there are areas of the CNS such as the choroid plexus and circumventricular organs that are not completely protected by the BBB and serve as entry points for certain viruses. Infected hematopoietic cells are also used as "Trojan horses" to transport viruses into the CNS. Finally, systemic viral infection can lead to inflammation-induced degradation of BBB, allowing viruses to literally go through CNS fissures(9).

Neuroinvasion via peripheral nerves (neuronal pathway)

Certain viruses infect and migrate through peripheral nerves as a second route into the CNS. In this process, neurons play a critical role, since these cells innervate peripheral organs and are therefore used by viruses as a gateway to the CNS. An alternative route for neuroinvasion is transport through olfactory neurons(5). This pathway is an excellent way to access CNS for viruses that enter the body through the intranasal route7,10.

Probable mechanism of SARS-CoV-2 neurological infection

Human coronaviruses (HCoV) contain four structural proteins (E, M, N and S). The main determinant of SARS-CoV-2 cell tropism is the S protein, which binds to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), a membrane receptor on host cells11and is present in different organs, including lung parenchyma, airway epithelia, nasal mucosa, gastrointestinal tract, renal, urinary, lymphoid tissues, reproductive organs, vascular endothelium and brain(11). Regarding its distribution in the brain, ACE2 is expressed in glial cells and neurons(12), as well as in the cerebral vasculature13. The complete interaction of the virus with the ACE2 receptor is enabled once the viral S protein is cleaved by the surface protease (transmembrane serine protease 2) scarcely present in the brain (brainstem, temporal lobe and occipital lobe)13. In addition to the ACE2 receptor, other important receptors have been identified such as dipeptidyl peptidase 4, present in the lower respiratory tract, kidney, small intestine, liver and immune system cells14and recently the neuropilin-1 receptor (NRP1), whose increased expression in respiratory and olfactory endothelial and epithelial cells may facilitate the entry and dissemination of SARS-CoV-215,16. Cathepsin L and the CD147 receptor have also been found to play an important role in the initial viral interaction with the host cell and are widely distributed in the CNS13,17.

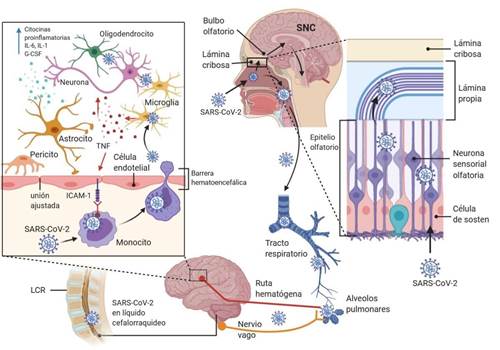

SARS-CoV-2 most likely reaches the CNS through neuronal projections via the olfactory nerve17. The unique anatomical organization of the olfactory nerves and olfactory bulb in the nasal cavity and prosencephalon effectively makes it a channel between the nasal epithelium and the CNS(7), especially in the early stages of infection (Figure 2)18. After penetrating the brain, the virus can spread quickly to other specific areas of the brain, such as the thalamus and the brainstem19,20. The importance of the presence of the virus in the brainstem should be emphasized, since this structure contains the medulla oblongata, which is the primary respiratory control center21and in the olfactory tissues, whose viral invasion could cause olfactory dysfunction in those affected22. Moreover, it is postulated that SARS-CoV-2 can advance the CNS from the periphery via retrograde and transsynaptic neuronal transport, especially afferent from the vagus nerve23and with increasing findings that SARS CoV-2 infects cells in the gastrointestinal tract, the neuroinvasive potential could even encompass the enteric nervous system24.

Although the hematogenous pathway seems impossible, theoretically SARS-CoV-2 could reach BBB through blood circulation, attacking the endothelial layer to access the CNS25. This invasion mechanism has been proposed for other HCVs, including SARS-CoV, because they can infect various myeloid cells and thus spread to other tissues, including CNS(figure 2)10.

Figure 2. Potential route of infection used by SARS-CoV-2 for neurological damage: Direct entry through the nasal epithelium, affecting the olfactory nerve, crossing the cribriform plate, gaining access to the olfactory bulb and spreading to other brain regions. On its way to the pulmonary tissue, it may reach the CNS from the periphery, from the vagus nerve and subsequently locate in the brain. In the case of a possible hematogenous route, it can damage and perforate the BBB or mobilize through leukocytes, by a mechanism called "Trojan horse". Figure modified from articleNervous system involvement after infection with COVID-19 and other coronaviruses. Brain Behav Immun. 2020.doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.03.031.

Neurologic clinical manifestations associated with COVID-19

Neurologic manifestations of COVID-19 occur in the central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral nervous system (SPS). CNS complications include encephalitis, meningitis, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM), myelitis, and encephalopathies (table 1). COVID-19-associated meningitis/encephalitis has become increasingly prevalent since it first appeared in mid-April 2020 in a Japanese patient whose cerebrospinal fluid sample was positive for SARS-CoV-226. This finding suggests that neurological symptoms can result from a direct viral invasion of the CNS, as demonstrated by Song et al27in brain autopsies of COVID-19 patients. Reports on myelitis associated with COVID-19 suggest that the spinal cord is a target organ for SARS-CoV-2. However, direct neuronal invasion of the virus in this region has not been demonstrated, but may be feasible since, like other organs of the human body, the spinal cord also expresses ACE228.

Table 1. Central nervous system complications in patients with COVID-19.

| Clinical manifestation | Study | Country | N | n (sex, age) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Encephalitis / Meningitis | Duong et al.(32) | United States | 1 | 1 (female, 41) | Moriguchi et al.(26) | Japan | 1 | 1 (male, 24) | Sohal et al.(33) | United States | 1 | 1 (male, 72) | Wong et al.(34) | United Kingdom | 1 | 1 (male, 40) | Ye et al.(35) | China | 1 | 1 (male, NM) | Barreto-Acevedo et al.(36) | Peru | 1 | 1 (male, 53) | Xiang et al.(37) | China | 1 | 1 (male, 53) | Pilotto et al.(38) | Italy | 1 | 1 (male, 60) | Varatharaj et al.(39) | United Kingdom | 125 | 7 (NM) | Paterson et al.(40) | United Kingdom | 43 | 2 (NM) | Bernard-Valnet et al.(41) | Switzerland | 2 | 2 (female, 64 y 67) |

| Other encephalopathies | Filatov et al.(42) | United States | 1 | 1 (male,74) | Poyiadji et al.(29) | United States | 1 | 1 (female, 50) | Dugue et al.(43) | United States | 1 | 1 (male, 6 weeks) | Helms et al.(44) | France | 58 | 40 (NM) | Mao et al.(5) | China | 214 | 16 (NM) | Paniz-Mondolfi et al.(45) | United States | 1 | 1 (male, 74) | Varatharaj et al.(39) | United Kingdom | 125 | 9 (NM) | Paterson et al.(40) | United Kingdom | 43 | 10 (NM) | Zhou et al.(46) | China | 1 | 1 (NM, 56) | ||||||||

| Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) | Zanin et al.(47) | Italy | 1 | 1 (female, 54) | Langley et al.(48) | United Kingdom | 1 | 1 (male, 53) | Paterson et al.(40) | United Kingdom | 43 | 9 (NM) | Novi et al.(49) | Italy | 1 | 1 (female, 64) | Zhang et al.(50) | United States | 1 | 1 (female, 40) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Myelitis | Zhao et al.(51) | China | 1 | 1 (female, 66) | AlKetbi et al.(52) | United Arab Emirates | 1 | 1 (male, 32) | Chow et al.(53) | Australia | 1 | 1 (male, 60) | Sotoca et al.(54) | Spain | 1 | 1 (female, 69) | Paterson et al.(40) | United Kingdom | 43 | 2 (NM) | Sarma et al.(55) | United States | 1 | 1 (female, 28) |

N: simple size (COVID-19 patients); n: number of cases; NM: not mentioned

Manifestations such as encephalopathy and ADEM may be the result of indirect damage to the infection, where the altered response of the immune system and the "cytokine storm" are the mechanisms involved, the observations of which are more noticeable in critically ill patients25,29. Symptoms such as headache, neck stiffness, altered state of consciousness, lethargy and irritability, despite not being specific symptoms, have been considered as neurological manifestations, some present in the medium to long term after the disease30,31).

Neurological findings of COVID-19 and the peripheral nervous system (PNS) are represented by olfactory and gustatory dysfunctions, Guillain-Barré syndrome and variants, rhabdomyolysis and other muscle diseases (table 2). The early onset of anosmia and ageusia indicates potential neurologic damage during disease development. Therefore, chemosensory impairment is thought to be at least 10 times more common in positive COVID-19 cases56. Since these alterations have been well documented, surveillance of olfactory and gustatory disorders has been suggested as a tool to detect suspected cases of infection56,57or as indicators of severity for the disease due to the prognostic potential they represent56, motivating their inclusion within early warning features for the disease58, as they are considered by many investigations as important symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 infection57.

Table 2. Peripheral nervous system complications and cerebrovascular disease in patients with COVID-19.

| Clinical manifestation | Study | Countries | N | n (sex, age) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNS disease | ||||

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | Virani et al.(60) | United States | 1 | 1 (male, 54) |

| Zhao et al.(64) | China | 1 | 1 (female, 61) | |

| Toscano et al.(59) | Italy | 5 | 5 (NM) | |

| Camdessanche et al.(65) | France | 1 | 1 (male, 64) | |

| El Otmani et al.(66) | Morocco | 1 | 1 (female, 70) | |

| Guijarro-Castro et al.(67) | Spain | 1 | 1 (male, 70) | |

| Paterson et al.(40) | United Kingdom | 43 | 7 (NM) | |

| Padroni et al.(68) | Italy | 1 | 1 (female, 70) | |

| Sedaghat et al.(69) | Iran | 1 | 1 (male, 65) | |

| Sancho-Saldaña et al.(70) | Spain | 1 | 1 (female, 56) | |

| Oguz -Akarsu et al.(71) | Turkey | 1 | 1 (female, 53) | |

| Coen et al.(72) | Switzerland | 1 | 1 (male, 70) | |

| Paybast et al.(73) | Iran | 2 | 2 (male and female, 38 and 14 years old) | |

| Scheidl et al.(74) | Germany | 1 | 1 (female, 54) | |

| VGBS variants and other neuropathies | Gutiérrez-Ortiz et al.(61) | Spain | 1 | 1 (male, 70), Miller Fisher syndrome |

| Dinkin et al.(75) | United States | 1 | 1 (male, 36), Miller Fisher syndrome | |

| Dinkin et al.(75) | United States | 1 | 1 (female, 71), ophthalmoplegia | |

| Sedaghat et al.(69) | Iran | 1 | 1 (male, 65), acute motor sensory axonal neuropathy (AMSAN) | |

| Restivo et al.(76) | Italy | 3 | 3 (two male and one female, 64 to 71 years old), myasthenia gravis | |

| Caamaño et al.(77) | Spain | 1 | 1 (male, 61), facial diplegia | |

| Pellitero et al.(78) | United States | 1 | 1 (female, 30), acute vestibular | |

| Rhabdomyolysis and other muscle diseases | Jin et al.(79) | China | 1 | 1 (male, 60) |

| Sing et al.(80) | United States | 4 | 4 (NM) | |

| Suwanwongse et al.(81) | United States | 1 | 1 (male, 88) | |

| Gefen et al.(82) | United States | 1 | 1 (male, 16) | |

| Olfactory and / or taste dysfunction | Beltrán‐Corbellini et al.(83) | Spain | 79 | 25 and 28 patients reported olfactory and gustatory dysfunction, respectively |

| Haehner et al.(84) | Germany | 34 | 22 patients reported olfactory and gustatory dysfunction | |

| Hornuss et al.(85) | Germany | 45 | 18, 20 and 7 patients reported anosmia, hyposmia and normosmia, respectively | |

| Giacomelli et al.(22) | Italy | 59 | 31 and 37 patients reported olfactory and gustatory dysfunction | |

| Klopfenstein et al.(86) | France | 114 | 54 and 46 patients reported anosmia and dysgeusia, respectively | |

| Lechien et al.(57) | Belgium,France,Spain and Italy | 417 | 357 and 342 patients reported olfactory and gustatory dysfunction, respectively | |

| Moein et al.(87) | Iran | 60 | 59 and 14 patients reported gustatory and olfactory dysfunction, respectively | |

| Vaira et al.(88) | Italy | 72 | 39 and 44 patients reported gustatory and olfactory dysfunction, respectively | |

| Yan et al.(56) | United States | 59 | 42 and 40 patients reported gustatory and olfactory dysfunction, respectively | |

| Lee et al.(89) | South Korea | 3191 | 389 and 353 patients reported olfactory and gustatory dysfunction, respectively | |

| Mao et al.(5) | China | 214 | 11 and 12 patients reported olfactory and gustatory dysfunction, respectively | |

| Bénézit et al.(90) | France | 68 | 51 and 63 patients reported olfactory and gustatory dysfunction, respectively | |

| Cerebrovascular disease | ||||

| Ischemic stroke | Li et al.(91) | China | 219 | 10 (NM) |

| Helms et al.(44) | France | 58 | 3 (NM) | |

| Klok et al.(92) | Netherlands | 184 | 5 (NM) | |

| Merkler et al.(93) | United States | 1916 | 31 (NM) | |

| Avula et al.(94) | United States | 4 | 4 (NM) | |

| Beyrouti et al.(95) | United Kingdom | 6 | 6 (five male and one male, 53 to 85 years old) | |

| Morassi et al.(96) | Italy | 6 | 4 (three male and one female, 75 to 82 years old) | |

| Varatharaj et al.(39) | United Kingdom | 125 | 57 (NM) | |

| Paterson et al.(40) | United Kingdom | 43 | 8 (NM) | |

| Mao et al.(5) | China | 214 | 6 (NM) | |

| Intracerebral hemorrhage | Li et al.(91) | China | 219 | 1 (NM) |

| Hernández-Fernández et al.(97) | Spain | 1683 | 5 (NM) | |

| Sharifi-Razavi et al.(98) | Iran | 1 | 1 (male, 79 years) | |

| Dogra et al.(99) | United States | 755 | 33 (NM) | |

| Varatharaj et al.(39) | United Kingdom | 125 | 9 (NM) | |

| Pavlov et al.(100) | Russia | 1200 | 3 (NM) | |

N: simple size (COVID-19 patients); n: number of cases; NM: not mentioned

Reports of Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) and axonal demyelinating variants associated with COVID-19 usually have a post-infectious profile (range 5-10 days)59. However, cases of GBS with a "parainfectious" profile have been observed60, a fact which must be verified in future research. As well, cases of Miller-Fisher syndrome, a rare variant of GBS associated with an aberrant immune response to SARS-CoV-2 infection, were described61and discussed in detail intable 2.

SARS-CoV-2 has also been associated with acute cerebrovascular diseases such as bleeding and stroke, especially in patients with hypertension or coagulopathy62, and the presence of such complications is thought to be associated with more severe patients5and the elderly63.

DISCUSSION

This study found that the neurological manifestations of COVID-19 involved both CNS and PNS. The main limitations of the study are associated with the number of scientific papers reporting thein situdiscovery of the virus. In addition to the size of the population in which it is described, it is mostly the series of cases that provides evidence of such direct harm.

The probable mechanism by which SRAS-CoV-2 penetrates the CNS and causes damage to the brain is an olfactory transmucosal invasion mediated by olfactory neurons as demonstrated by in vitro and post mortem studies, where NRP1 is an important factor for the entry and infectivity of the olfactory epithelium by SARS-CoV-215,16, findings that partly justify the different neurological manifestations described in infected patients (table 1andtable 2).

The neurotropism of SARS-CoV-2 has already been documented27. This fact has been seen before in other HCoV infections such as SARS-CoV, where the virus was isolated from brain tissue12and OC43, where axonal (neuron - neuron) transport was shown to be the way the virus accesses and spreads within the CNS10. These reports show the nervous tropism of HCoV and therefore raise the hypothesis of the mechanism used by SARS-CoV-2 to invade the CNS, being the neuronal route the most likely, however, these findings must be verified with other studies mainly in animal models,in vitroand patient autopsies.

It is known that the Herpesviridae family can persist in the CNS101and although this event is less likely in RNA viruses, it is known from studies in mice infected with OC43that viral RNA persists for at least one year in cases where multiple sclerosis (MS) was observed following infection46. An important point to consider in SARS-CoV-2 infections, because if this virus has the capacity of latency in the CNS of "recovered" patients, then it could be a trigger for various late neurological and neurodegenerative complications such as MS, Parkinson's disease or produce relapses in predisposed individuals.

Olfactory and gustatory dysfunctions are increasingly common in patients with COVID-19 and are even suggested as pathogenic symptoms of the disease56. Loss of smell is a challenging clinical problem that has few proven diagnostic options. Some studies propose to carry out a rapid inhalation anosmia test using acetic acid even before other evaluations such as hyperthermia, cough and headache102. Even though this has not been observed in all reported COVID-19 cases, it would be important to adequately identify the presence of this variable and its likely association with the prognosis and subsequent development of serious neurologic manifestations in affected patients.

Although most current evidence suggests that direct damage or accumulation of thrombus in the alveoli would cause respiratory distress and failure, it may be partially related to the damage caused by the virus in the respiratory centers of the brain. This is due to the spread of SARS-CoV-2 into the brain, particularly the encephalic bulb, since this structure contains nuclei that regulate the respiratory rate and alterations to these components result in increased or decreased respiratory effort66. However, although this is a valid hypothesis, there is a need to consider other signs of brain dysfunction, which is another reason to pursue studies on the severity of harm that COVID-19 can cause.

Clinical evidence of neurological impairment in COVID-19 patients is mostly from Asia, Europe and North America. It also demonstrates the need to document them in South America in order to consider them, in many instances, as warning signs. Likewise, this can motivate the development of preliminary detection strategies to avoid fatal outcomes, especially in a scenario of quarantine or social restriction, where they can be dismissed by the already known respiratory manifestations. In this regard, several specialists expressed concern that during this pandemic, visits for myocardial infarction and stroke decreased. However, deaths due to the same causes have risen dramatically. The evidence is that in New York City, they have increased by 800%103.

CONCLUSIONS

Increasing evidence of neurologic manifestations demonstrates that SARS-CoV-2 infection is not limited to the respiratory system and that the virus has the ability to migrate to nervous tissue and cause damage. However, the scope and complications are not entirely clear; therefore, it is necessary to continue to document and report these neurological complications that can occur in COVID-19 patients. Likewise, given the increase in the number of deaths reported suddenly and, in some cases, due to neurological damage, remaining in mandatory isolation without determining the presence or severity of this type of manifestations would represent a risk that could worsen the patient's prognosis, which would result in a high chance of death or disability.

REFERENCES

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Symptoms of Coronavirus [Internet]. CDC COVID-19. 2020 [Citado el 1 de diciembre de 2020]. Disponible en: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/symptoms-testing/symptoms.html [ Links ]

2. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. COVID-19 transmission-up in the air [Internet]. Lancet Respir Med. 2020 [Citado el 1 de diciembre de 2020]; 8(12):1159. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30514-2 [ Links ]

3. Johns Hopkins University & Medicine. Coronavirus Resource Center [Internet]. Johns Hopkins University [Citado el 1 de diciembre de 2020]. Disponible en: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/ [ Links ]

4. Shaman J, Galanti M. Will SARS-CoV-2 become endemic? [Internet]. Science. 2020 [Citado el 1 de diciembre de 2020]; 370(6516):527-529. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abe5960 [ Links ]

5. Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, Hu Y, Chen S, He Q, et al. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020; 77(6):683-690. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1001%2Fjamaneurol.2020.1127 [ Links ]

6. Moreno-Zambrano D, Arévalo-Mora M, Freire-Bonifacini A, García-Santibanez R, Santibáñez-Vásquez R. Neurologic manifestations associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection: A neuro-review of COVID-19. Rev ecuatoriana Neurol. 2020; 29(1):115-124. DOI: https://doi.org/10.46997/REVECUATNEUROL29100115 [ Links ]

7. Koyuncu OO, Hogue IB, Enquist LW. Virus infections in the nervous system. Cell Host Microbe. 2013; 13(4):379-393. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2013.03.010 [ Links ]

8. Suen WW, Prow NA, Hall RA, Bielefeldt-Ohmann H. Mechanism of west Nile virus neuroinvasion: A critical appraisal. Viruses. 2014; 6(7):2796-825. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/v6072796 [ Links ]

9. Swanson PA, McGavern DB. Viral diseases of the central nervous system. Curr Opin Virol. 2015; 11:44-54. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coviro.2014.12.009 [ Links ]

10. Desforges M, Le Coupanec A, Dubeau P, Bourgouin A, Lajoie L, Dubé M, et al. Human Coronaviruses and Other Respiratory Viruses: Underestimated Opportunistic Pathogens of the Central Nervous System? [ Internet]. Viruses. 2019 [ Citado el 1 de diciembre de 2020]; 12(1):14. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/v12010014 [ Links ]

11. Hulswit RJG, de Haan CAM, Bosch B-J. Chapter two - Coronavirus spike protein and tropism changes. 2016; 96:29-57. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.aivir.2016.08.004 [ Links ]

12. Baig AM, Khaleeq A, Ali U, Syeda H. Evidence of the COVID-19 virus targeting the CNS: Tissue distribution, host-virus interaction, and proposed neurotropic mechanisms. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2020; 11(7):995-998. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/acschemneuro.0c00122 [ Links ]

13. Toljan K. Letter to the editor regarding the viewpoint "Evidence of the COVID-19 virus targeting the CNS: Tissue distribution, host-virus interaction, and proposed neurotropic mechanism". ACS Chem Neurosci. 2020; 11(8):1192-1194. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/acschemneuro.0c00174 [ Links ]

14. Boonacker E, Van Noorden CJF. The multifunctional or moonlighting protein CD26/DPPIV. Eur J Cell Biol. 2003; 82(2):53-73. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1078/0171-9335-00302 [ Links ]

15. Daly JL, Simonetti B, Klein K, Chen K-E, Williamson MK, Antón-Plágaro C, et al. Neuropilin-1 is a host factor for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Science. 2020; 370(6518):861-865. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abd3072 [ Links ]

16. Cantuti-Castelvetri L, Ojha R, Pedro LD, Djannatian M, Franz J, Kuivanen S, et al. Neuropilin-1 facilitates SARS-CoV-2 cell entry and infectivity. Science. 2020; 370(6518):856-860. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abd2985 [ Links ]

17. St-Jean JR, Jacomy H, Desforges M, Vabret A, Freymuth F, Talbot PJ. Human Respiratory Coronavirus OC43: Genetic Stability and Neuroinvasion. J Virol. 2004; 78(16):8824-8834. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.78.16.8824-8834.2004 [ Links ]

18. Mori I. Transolfactory neuroinvasion by viruses threatens the human brain. Acta Virol. 2015; 59(04):338-349. DOI: 10.4149 / av_2015_04_338 [ Links ]

19. Li K, Wohlford-Lenane C, Perlman S, Zhao J, Jewell AK, Reznikov LR, et al. Middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus causes multiple organ damage and lethal disease in mice transgenic for human dipeptidyl peptidase 4. J Infect Dis. 2016; 213(5):712-722. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiv499 [ Links ]

20. Netland J, Meyerholz DK, Moore S, Cassell M, Perlman S. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection causes neuronal death in the absence of encephalitis in mice transgenic for human ACE2. J Virol. 2008; 82(15):7264-7275. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.00737-08 [ Links ]

21. Conde Cardona G, Quintana Pájaro LD, Quintero Marzola ID, Ramos Villegas Y, Moscote Salazar LR. Neurotropism of SARS-CoV 2: Mechanisms and manifestations [Internet]. J Neurol Sci. 2020 [Citado el 1 de diciembre de 2020]; 412:116824. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2020.116824 [ Links ]

22. Giacomelli A, Pezzati L, Conti F, Bernacchia D, Siano M, Oreni L, et al. Self-reported olfactory and taste disorders in patients with severe acute respiratory coronavirus 2 infection: A cross-sectional study. Clin Infect Dis. 2020; 71(15):889-890. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1093%2Fcid%2Fciaa330 [ Links ]

23. Li Y-C, Bai W-Z, Norio H, Tsuyako H, Takahide T, Yoichi S, et al. Neurotropic virus tracing suggests a membranous coating mediated mechanism for transsynaptic communication. J Comp Neurol. 2013; 521(1):203-212. DOI: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/cne.23171 [ Links ]

24. Wong SH, Lui RN, Sung JJ. Covid-19 and the digestive system. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020; 35(5):744-748. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/jgh.15047 [ Links ]

25. Das G, Mukherjee N, Ghosh S. Neurological insights of COVID-19 pandemic. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2020; 11(9):1206-1209. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/acschemneuro.0c00201 [ Links ]

26. Moriguchi T, Harii N, Goto J, Harada D, Sugawara H, Takamino J, et al. A first case of meningitis/encephalitis associated with SARS-Coronavirus-2. Int J Infect Dis. 2020; 94:55-58. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.062 [ Links ]

27. Song E, Zhang C, Israelow B, Lu-Culligan A, Prado AV, Skriabine S, et al. Neuroinvasion of SARS-CoV-2 in human and mouse brain [Internet]. bioRxiv. 2020 [Citado el 1 de diciembre de 2020]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.25.169946 [ Links ]

28. Nemoto W, Yamagata R, Nakagawasai O, Nakagawa K, Hung W-Y, Fujita M, et al. Effect of spinal angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 activation on the formalin-induced nociceptive response in mice [Internet]. Eur J Pharmacol. 2020 [Citado el 1 de diciembre de 2020]; 872:172950. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2020.172950 [ Links ]

29. Poyiadji N, Shahin G, Noujaim D, Stone M, Patel S, Griffith B. COVID-19-associated acute hemorrhagic necrotizing encephalopathy: Imaging features [Internet]. Radiology. 2020 [Citado el 1 de diciembre de 2020]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2020201187 [ Links ]

30. Yin R, Feng W, Wang T, Chen G, Wu T, Chen D, et al. Concomitant neurological symptoms observed in a patient diagnosed with coronavirus disease 2019. J Med Virol. 2020; 92(10):1782-1784. DOI: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/jmv.25888 [ Links ]

31. Xu X-W, Wu X-X, Jiang X-G, Xu K-J, Ying L-J, Ma C-L, et al. Clinical findings in a group of patients infected with the 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS-Cov-2) outside of Wuhan, China: Retrospective case series [Internet]. BMJ. 2020 [Citado el 1 de diciembre de 2020]; 368:m606. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m606 [ Links ]

32. Duong L, Xu P, Liu A. Meningoencephalitis without respiratory failure in a young female patient with COVID-19 infection in downtown Los Angeles, early april 2020. Brain Behav Immun. 2020; 87:33. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.024 [ Links ]

33. Sohal S, Mansur M. COVID-19 presenting with seizures [Internet]. IDCases. 2020 [Citado el 1 de diciembre de 2020]; 20:e00782. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idcr.2020.e00782 [ Links ]

34. Wong PF, Craik S, Newman P, Makan A, Srinivasan K, Crawford E, et al. Lessons of the month 1: A case of rhombencephalitis as a rare complication of acute COVID-19 infection. Clin Med. 2020; 20(3):293-294. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmed.2020-0182 [ Links ]

35. Ye M, Ren Y, Lv T. Encephalitis as a clinical manifestation of COVID-19. Brain Behav Immun. 2020; 88:945-946. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.017 [ Links ]

36. Barreto-Acevedo E, Mariños E, Espino P, Troncoso J, Urbina L, Valer N. Encefalitis aguda en pacientes COVID-19: primer reporte de casos en Perú. Rev Neuropsiquiatr. 2020; 83(2):116-122. DOI: https://doi.org/10.20453/rnp.v83i2.3754 [ Links ]

37. Xiang P, Xu XM, Gao LL, Wang HZ, Xiong HF, Li RH. First case of 2019 novel coronavirus disease with Encephalitis [Internet]. ChinaXiv. 2020 [Citado el 1 de diciembre de 2020]; 202003:0015. Disponible en: https://bit.ly/3f2aj2c [ Links ]

38. Pilotto A, Odolini S, Masciocchi S, Comelli A, Volonghi I, Gazzina S, et al. Steroid-responsive encephalitis in coronavirus disease 2019. Ann Neurol. 2020; 88(2):423-427. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.25783 [ Links ]

39. Varatharaj A, Thomas N, Ellul MA, Davies NWS, Pollak TA, Tenorio EL, et al. Neurological and neuropsychiatric complications of COVID-19 in 153 patients: a UK-wide surveillance study. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2020; 7(10):875-882. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30287-X [ Links ]

40. Paterson RW, Brown RL, Benjamin L, Nortley R, Wiethoff S, Bharucha T, et al. The emerging spectrum of COVID-19 neurology: clinical, radiological and laboratory findings. Brain. 2020; 143(10):3104-3120. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awaa240 [ Links ]

41. Bernard-Valnet R, Pizzarotti B, Anichini A, Demars Y, Russo E, Schmidhauser M, et al. Two patients with acute meningoencephalitis concomitant with SARS-CoV-2 infection [Internet]. Eur J Neurol. 2020 [Citado el 1 de diciembre de 2020]; 27(9):e43-e44. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.14298 [ Links ]

42. Filatov A, Sharma P, Hindi F, Espinosa PS. Neurological complications of coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Encephalopathy [Internet]. Cureus. 2020 [Citado el 1 de diciembre de 2020]; 12(3):e7352. DOI: 10.7759 / cureus.7352 [ Links ]

43. Dugue R, Cay-Martínez KC, Thakur KT, Garcia JA, Chauhan L V., Williams SH, et al. Neurologic manifestations in an infant with COVID-19. Neurology. 2020; 94(24):1100-1102. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.0000000000009653 [ Links ]

44. Helms J, Kremer S, Merdji H, Clere-Jehl R, Schenck M, Kummerlen C, et al. Neurologic features in severe SARS-CoV-2 infection. N Engl J Med. 2020; 382(23):2268-2270. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmc2008597 [ Links ]

45. Paniz-Mondolfi A, Bryce C, Grimes Z, Gordon RE, Reidy J, Lednicky J, et al. Central nervous system involvement by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus -2 (SARS-CoV-2). J Med Virol. 2020; 92(7):699-702. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.25915 [ Links ]

46. Zhou L, Zhang M, Wang J, Gao J. Sars-Cov-2: Underestimated damage to nervous system [Internet]. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020 [Citado el 1 de diciembre de 2020]; 36:101642. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101642 [ Links ]

47. Zanin L, Saraceno G, Panciani PP, Renisi G, Signorini L, Migliorati K, et al. SARS-CoV-2 can induce brain and spine demyelinating lesions. Acta Neurochir. 2020; 162(7):1491-1494. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-020-04374-x [ Links ]

48. Langley L, Zeicu C, Whitton L, Pauls M. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) associated with COVID-19 [Internet]. BMJ Case Rep. 2020 [Citado el 1 de diciembre de 2020]; 13(12):e239597. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2020-239597 [ Links ]

49. Novi G, Rossi T, Pedemonte E, Saitta L, Rolla C, Roccatagliata L, et al. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis after SARS-CoV-2 infection [Internet]. Neurol - Neuroimmunol Neuroinflammation. 2020 [Citado el 1 de diciembre de 2020]; 7(5):e797. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1212%2FNXI.0000000000000797 [ Links ]

50. Zhang T, Hirsh E, Zandieh S, Rodricks MB. COVID-19-associated acute multi-infarct encephalopathy in an asymptomatic CADASIL patient [Internet]. Neurocrit Care. 2020 [Citado el 1 de diciembre de 2020]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-020-01119-7 [ Links ]

51. Zhao K, Huang J, Dai D, Feng Y, Liu L, Nie S. Acute myelitis after SARS-CoV-2 infection: a case report [Internet]. medRxiv. 2020 [Citado el 1 de diciembre de 2020]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.16.20035105 [ Links ]

52. AlKetbi R, AlNuaimi D, AlMulla M, AlTalai N, Samir M, Kumar N, et al. Acute myelitis as a neurological complication of Covid-19: A case report and MRI findings. Radiol Case Reports. 2020; 15(9):1591-1595. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radcr.2020.06.001 [ Links ]

53. Chow CCN, Magnussen J, Ip J, Su Y. Acute transverse myelitis in COVID-19 infection [Internet]. BMJ Case Rep. 2020 [Citado el 1 de diciembre de 2020]; 13(8):e236720. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2020-236720 [ Links ]

54. Sotoca J, Rodríguez-Álvarez Y. COVID-19-associated acute necrotizing mielitis [Internet]. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2020 [Citado el 1 de diciembre de 2020]; 7(5):e803. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1212%2FNXI.0000000000000803 [ Links ]

55. Sarma D, Bilello LA. Case report of acute transverse myelitis following novel coronavirus infection. Clin Pract Cases Emerg Med. 2020; 4(3):321- 323. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5811%2Fcpcem.2020.5.47937 [ Links ]

56. Yan CH, Faraji F, Prajapati DP, Boone CE, DeConde AS. Association of chemosensory dysfunction and Covid-19 in patients presenting with influenza-like symptoms. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2020; 10(7):806-813. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/alr.22579 [ Links ]

57. Lechien JR, Chiesa-Estomba CM, De Siati DR, Horoi M, Le Bon SD, Rodriguez A, et al. Olfactory and gustatory dysfunctions as a clinical presentation of mild-to-moderate forms of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a multicenter European study. Eur Arch Oto-Rhino-Laryngology. 2020; 277(8):2251-2261. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2Fs00405-020-05965-1 [ Links ]

58. Saad M, Omrani AS, Baig K, Bahloul A, Elzein F, Matin MA, et al. Clinical aspects and outcomes of 70 patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection: a single-center experience in Saudi Arabia. Int J Infect Dis. 2014; 29:301-306. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2014.09.003 [ Links ]

59. Toscano G, Palmerini F, Ravaglia S, Ruiz L, Invernizzi P, Cuzzoni MG, et al. Guillain-Barré Syndrome Associated with SARS-CoV-2. N Engl J Med. 2020; 382(26):2574-2576. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmc2009191 [ Links ]

60. Virani A, Rabold E, Hanson T, Haag A, Elrufay R, Cheema T, et al. Guillain-Barré Syndrome associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection [Internet]. IDCases. 2020 [Citado el 1 de diciembre de 2020]; 20:e00771. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idcr.2020.e00771 [ Links ]

61. Gutiérrez-Ortiz C, Méndez A, Rodrigo-Rey S, San Pedro-Murillo E, Bermejo-Guerrero L, Gordo-Mañas R, et al. Miller Fisher syndrome and polyneuritis cranialis in COVID-19 [Internet]. Neurology. 2020 [Citado el 1 de diciembre de 2020]; 95(5): e601-e605. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000009619 [ Links ]

62. Wang H-Y, Li X-L, Yan Z-R, Sun X-P, Han J, Zhang B-W. Potential neurological symptoms of COVID-19 [Internet]. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2020 [Citado el 1 de diciembre de 2020]; 13:175628642091783. DOI: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1756286420917830 [ Links ]

63. Liu K, Pan M, Xiao Z, Xu X. Neurological manifestations of the coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic 2019-2020 [Internet]. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2020 [Citado el 1 de diciembre de 2020]. DOI: http://jnnp.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/jnnp-2020-323177 [ Links ]

64. Zhao H, Shen D, Zhou H, Liu J, Chen S. Guillain-Barré syndrome associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection: causality or coincidence?. Lancet Neurol. 2020; 19(5):383-384. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30109-5 [ Links ]

65. Camdessanche J-P, Morel J, Pozzetto B, Paul S, Tholance Y, Botelho-Nevers E. COVID-19 may induce Guillain-Barré syndrome. Rev Neurol. 2020; 176(6):516-518. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurol.2020.04.003 [ Links ]

66. El Otmani H, El Moutawakil B, Rafai M-A, El Benna N, El Kettani C, Soussi M, et al. Covid-19 and Guillain-Barré syndrome: More than a coincidence!. Rev Neurol. 2020; 176(6):518-519. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.neurol.2020.04.007 [ Links ]

67. Guijarro-Castro C, Rosón-González M, Abreu A, García-Arratibel A, Ochoa-Mulas M. Síndrome de Guillain-Barré tras infección por SARS-CoV-2. Comentarios tras la publicación de 16 nuevos casos. Neurología. 2020; 35(6):412-415. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nrl.2020.06.002 [ Links ]

68. Padroni M, Mastrangelo V, Asioli GM, Pavolucci L, Abu-Rumeileh S, Piscaglia MG, et al. Guillain-Barré syndrome following COVID-19: new infection, old complication?. J Neurol. 2020; 267(7):1877-1879. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2Fs00415-020-09849-6 [ Links ]

69. Sedaghat Z, Karimi N. Guillain Barre syndrome associated with COVID-19 infection: A case report. J Clin Neurosci. 2020; 76:233-235. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.jocn.2020.04.062 [ Links ]

70. Sancho-Saldaña A, Lambea-Gil Á, Liesa JLC, Caballo MRB, Garay MH, Celada DR, et al. Guillain-Barré syndrome associated with leptomeningeal enhancement following SARS-CoV-2 infection [Internet]. Clin Med. 2020 [Citado el 1 de diciembre de 2020]; 20(4):e93-4. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.7861%2Fclinmed.2020-0213 [ Links ]

71. Oguz-Akarsu E, Ozpar R, Mirzayev H, Acet-Ozturk NA, Hakyemez B, Ediger D, et al. Guillain-Barré Syndrome in a Patient with Minimal Symptoms of COVID-19 Infection [Internet]. Muscle Nerve. 2020 [Citado el 1 de diciembre de 2020]; 62(3). DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1002%2Fmus.26992 [ Links ]

72. Coen M, Jeanson G, Culebras Almeida LA, Hübers A, Stierlin F, Najjar I, et al. Guillain-Barré syndrome as a complication of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Brain Behav Immun. 2020; 87:111-112. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.bbi.2020.04.074 [ Links ]

73. Paybast S, Gorji R, Mavandadi S. Guillain-Barré syndrome as a neurological complication of novel COVID-19 infection. Neurologist. 2020; 25(4):101-103. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1097%2FNRL.0000000000000291 [ Links ]

74. Scheidl E, Diez Canseco D, Hadji-Naumov A, Bereznai B. Guillain-Barré syndrome during SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: A case report and review of recent literature. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2020; 25(2):204-207. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/jns.12382 [ Links ]

75. Dinkin M, Gao V, Kahan J, Bobker S, Simonetto M, Wechsler P, et al. COVID-19 presenting with ophthalmoparesis from cranial nerve palsy. Neurology. 2020; 95(5):221-223. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000009700 [ Links ]

76. Restivo DA, Centonze D, Alesina A, Marchese-Ragona R. Myasthenia Gravis associated qith SARS-CoV-2 infection. Ann Intern Med. 2020; 173(12):1027-1028. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7326/L20-0845 [ Links ]

77. Juliao Caamaño DS, Alonso Beato R. Facial diplegia, a possible atypical variant of Guillain-Barré syndrome as a rare neurological complication of SARS-CoV-2. J Clin Neurosci. 2020; 77:230-232. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.jocn.2020.05.016 [ Links ]

78. Escalada Pellitero S, Garriga Ferrer-Bergua L. Paciente con clínica neurológica como única manifestación de infección por SARS-CoV-2. Neurología. 2020; 35(4):271-272. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nrl.2020.04.010 [ Links ]

79. Jin M, Tong Q. Rhabdomyolysis as potential late complication associated with COVID-19. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020; 26(7):1618-1620. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2607.200445 [ Links ]

80. Singh B, Kaur P, Mechineni A, Maroules M. Rhabdomyolysis in COVID-19: Report of Four Cases [Internet]. Cureus. 2020 [Citado el 1 de diciembre de 2020]; 12(9):e10686. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.10686 [ Links ]

81. Suwanwongse K, Shabarek N. Rhabdomyolysis as a presentation of 2019 novel coronavirus disease [Internet]. Cureus. 2020 [Citado el 1 de diciembre de 2020]; 12(4):e7561. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.7759%2Fcureus.7561 [ Links ]

82. Gefen AM, Palumbo N, Nathan SK, Singer PS, Castellanos-Reyes LJ, Sethna CB. Pediatric COVID-19-associated rhabdomyolysis: a case report. Pediatr Nephrol. 2020; 35(8):1517-1520. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-020-04617-0 [ Links ]

83. Beltrán-Corbellini Á, Chico-García JL, Martínez-Poles J, Rodríguez-Jorge F, Natera-Villalba E, Gómez-Corral J, et al. Acute-onset smell and taste disorders in the context of COVID-19: a pilot multicentre polymerase chain reaction based case-control study. Eur J Neurol. 2020; 27(9):1738-1741. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.14273 [ Links ]

84. Haehner A, Draf J, Dräger S, de With K, Hummel T. Predictive value of sudden olfactory loss in the diagnosis of COVID-19. ORL. 2020; 82(4):175-180. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1159/000509143 [ Links ]

85. Hornuss D, Lange B, Schröter N, Rieg S, Kern WV, Wagner D. Anosmia in COVID-19 patients. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020; 26(10):1426-1427. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.cmi.2020.05.017 [ Links ]

86. Klopfenstein T, Kadiane-Oussou NJ, Toko L, Royer P-Y, Lepiller Q, Gendrin V, et al. Features of anosmia in COVID-19. Médecine Mal Infect. 2020; 50(5):436-439. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medmal.2020.04.006 [ Links ]

87. Moein ST, Hashemian SM, Mansourafshar B, Khorram-Tousi A, Tabarsi P, Doty RL. Smell dysfunction: a biomarker for COVID-19. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2020; 10(8):944-950. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/alr.22587 [ Links ]

88. Vaira LA, Deiana G, Fois AG, Pirina P, Madeddu G, De Vito A, et al. Objective evaluation of anosmia and ageusia in COVID-19 patients: Single-center experience on 72 cases. Head Neck. 2020; 42(6):1252-1258. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.26204 [ Links ]

89. Lee Y, Min P, Lee S, Kim S-W. Prevalence and Duration of Acute Loss of Smell or Taste in COVID-19 Patients [Internet]. J Korean Med Sci. 2020 [Citado el 1 de diciembre de 2020]; 35(18):e174. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3346%2Fjkms.2020.35.e174 [ Links ]

90. Bénézit F, Le Turnier P, Declerck C, Paillé C, Revest M, Dubée V, et al. Utility of hyposmia and hypogeusia for the diagnosis of COVID-19. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020; 20(9):1014-1015. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30297-8 [ Links ]

91. Li Y, Wang M, Zhou Y, Chang J, Xian Y, Mao L, et al. Acute cerebrovascular disease following COVID-19: A single center, retrospective, observational study [Internet]. SSRN Electron J. 2020 [Citado el 1 de diciembre de 2020]. DOI: 10.2139 / ssrn.3550025 [ Links ]

92. Klok FA, Kruip MJHA, van der Meer NJM, Arbous MS, Gommers D, Kant KM, et al. Confirmation of the high cumulative incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19: An updated analysis. Thromb Res. 2020; 191:148-50. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.041 [ Links ]

93. Merkler AE, Parikh NS, Mir S, Gupta A, Kamel H, Lin E, et al. Risk of ischemic stroke in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vs patients with influenza. JAMA Neurol. 2020; 77(11):1366-1372. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.2730 [ Links ]

94. Avula A, Nalleballe K, Narula N, Sapozhnikov S, Dandu V, Toom S, et al. COVID-19 presenting as stroke. Brain Behav Immun. 2020; 87:115-119. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.077 [ Links ]

95. Beyrouti R, Adams ME, Benjamin L, Cohen H, Farmer SF, Goh YY, et al. Characteristics of ischaemic stroke associated with COVID-19. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2020; 91(8):889-891. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2020-323586 [ Links ]

96. Morassi M, Bagatto D, Cobelli M, D'Agostini S, Gigli GL, Bnà C, et al. Stroke in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection: case series. J Neurol. 2020; 267(8):2185-2192. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-020-09885-2 [ Links ]

97. Hernández-Fernández F, Sandoval Valencia H, Barbella-Aponte RA, Collado-Jiménez R, Ayo-Martín Ó, Barrena C, et al. Cerebrovascular disease in patients with COVID-19: neuroimaging, histological and clinical description. Brain. 2020; 143(10):3089-3103. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awaa239 [ Links ]

98. Sharifi-Razavi A, Karimi N, Rouhani N. COVID-19 and intracerebral haemorrhage: causative or coincidental? [Internet]. New Microbes New Infect. 2020 [Citado el 1 de diciembre de 2020]; 35:100669. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nmni.2020.100669 [ Links ]

99. Dogra S, Jain R, Cao M, Bilaloglu S, Zagzag D, Hochman S, et al. Hemorrhagic stroke and anticoagulation in COVID-19 [Internet]. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2020 [Citado el 1 de diciembre de 2020]; 29(8):104984. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2020.104984 [ Links ]

100. Pavlov V, Beylerli O, Gareev I, Torres Solis LF, Solís Herrera A, Aliev G. COVID-19-Related Intracerebral Hemorrhage [Internet]. Front Aging Neurosci. 2020 [Citado el 1 de diciembre de 2020]; 12:600172. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2020.600172 [ Links ]

101. Steiner I, Benninger F. Manifestations of Herpes virus infections in the nervous system. Neurol Clin. 2018; 36(4):725-738. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ncl.2018.06.005 [ Links ]

102. Duque Parra JE, Duque Montoya D, Peláez FJC. El COVID-19 también afecta el sistema nervioso por una de sus compuertas: el órgano vascular de la lámina terminal y el nervio olfatorio. Alerta Neurológica, prueba de disosmia o anosmia puede ayudar a un diagnóstico rápido. Int J Odontostomat. 2020; 14(3):285-187. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-381X2020000300285 [ Links ]

103. Blanco D. Un reconocido neurocirujano advirtió que el coronavirus afecta al sistema nervioso central [Internet]. INFOBAE [Citado el 1 de diciembre del 2020]. Disponible en: https://bit.ly/360jlJ3 [ Links ]

Received: June 16, 2020; Accepted: February 22, 2021

texto en

texto en