Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista de la Facultad de Medicina Humana

versión impresa ISSN 1814-5469versión On-line ISSN 2308-0531

Rev. Fac. Med. Hum. vol.22 no.4 Lima oct./dic. 2022 Epub 12-Oct-2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.25176/rfmh.v22i4.4806

Review article

Complications associated with remote work during the COVID-19 pandemic: A quick review complications associated with remote work

1National Institute of Health-National Center for Occupational Health and Environmental Protection for Health, Lima, Peru.

Introduction:

This review identifies and describes remote work’s main outcomes and complications during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods:

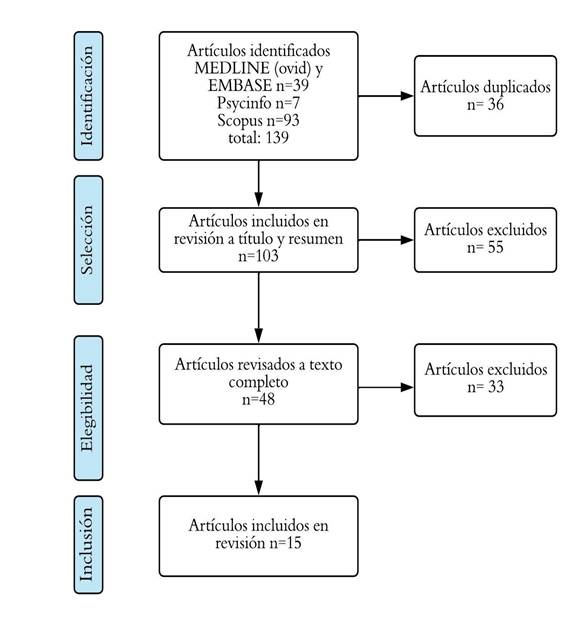

A systematic review of the literature was carried out that included observational studies whose population or partly carried out remote work published between March 1, 2020 and November 30, 2020. The descriptors were adapted to the bases: MEDLINE (Ovid), EMBASE, Scopus, and Psycinfo. 139 studies were found, and 15 articles were included in this synthesis.

Results:

A total 18,818 workers were reported, of which women represented 18.2%-100% of the population. The findings describe the increased use of electronic devices, sedentary lifestyle, anxiety, depression, feelings of loneliness, sleep disorders, and musculoskeletal pain in remote workers.

Conclusions:

Therefore, it is necessary to provide assistance and education to the remote worker to improve their conditions, reduce the associated complications and positively impact their lifestyle.

Keywords: COVID-19; Telecommuting; Physical activity; Occupational health; Musculoskeletal disorder. (Source: MeSH NLM).

INTRODUCTION

The current pandemic caused by the new coronavirus impacts the health of workers and the conditions of the workplace, who have had to adapt in order to reduce the risk of contagion1. Among the measures recommended at the labor level, the implementation of remote work (RT)2,3stands out, which urged subjects with little experience to work from home, and reorganize spaces and schedules to continue working4.

The job change in an unusual context has given rise to difficulties and risks in the execution of work4,5. Research before the pandemic shows inconclusive results between RT and associated outcomes6-13. Some studies show that TR provides employees with flexibility, work autonomy, stress reduction12, and work-home conflict6; in addition to improving commitment7and performance8.

However, there is also evidence of a null14and even negative effect of TR associated with isolating behavior, increased conflict between work and home responsibilities15, musculoskeletal pain16-18, burnout5, overload mental, fatigue19, as well as the decrease in interaction and work performance20. The ambiguity of the findings can be attributed to the variability in the RT implementation processes associated with the context21. During the quarantine period, physical and mental health problems have been observed in people who perform RT, such as social isolation22, overexposure to visual screens, increased time spent sitting, decreased level of physical activity23,24, as well as sleep problems25depressive symptomatology26,27and anxiety27which need to be addressed.

Therefore, this review of the scientific literature aimed to identify and describe the outcomes associated with health in workers who perform RT in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

METHODS

Information sources

A systematic literature review was conducted to identify information and summarize relevant findings28. The search was performed in the MEDLINE (Ovid), EMBASE, Scopus, and Psycinfo databases. The PI/ECO format systematic search strategy was structured, incorporating controlled language descriptors (Mesh) as detailed inTable 1.

Table 1. Search strategy.

| Indicator | Thesaurus/free terms |

| P | “Computer worker*”, “office employee*”, “remote-employee”, “office-worker*”, “computer-based worker*”, “White-collar worker”, “teacher*” |

| I/E | “telecommuting”, “telework”, “remote Work”, “home- office”, “Work from home” / COVID-19, coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2 |

| O1* | “Musculoskeletal pain”, “musculoskeletal disease*”, “musculoskeletal disorder*”, “musculoskeletal disconfort”, “Work-related musculoskeletal disorder”, “musculoskeletal injur*¨” |

| O2* | “Physical activity”, “exercise”, “physical inactivity”, “sedentary behaviour/ behavior” |

| O3* | ” food habits”, “nutrition”, “diet” |

| O4* | “Occupational stress”, “anxiety”, “depression”, “psychological risk” |

| O5* | “postural balance”, “posture” |

| O6* | “sleep disorder”, “sleep deprivation”, “sleep disturbance” |

Eligibility criteria

The search was limited to studies published from March to November 2020. The inclusion criteria were: i) Observational studies ii) the study population or part of it must be remote workers. iii) The workers must have adopted this modality after the declaration of a public health emergency of international importance (ESPII) according to the WHO(29)or during the local quarantine period. The following were excluded: i) Studies in health workers ii) language other than Spanish, English or Portuguese.

Selection of studies

The search was carried out, and the data was exported to the Rayyan web application30where duplicate data was eliminated. Next, the title and abstract were read as the full text of the potentially relevant articles was to determine their eligibility (LCA, JRR).

Discrepancies were resolved by consensus. The selection process is detailed in the PRISMA flowchart inFigure 1.

An Excel program form was used for the extraction of the following data: author, year of publication, the population of interest, country, and description of associated outcomes observed.

RESULTS

139 relevant references were identified and 15 articles were included in this review. 18,818 participants were reported, and the percentage of women varied between 18.2%-100%. The outcomes associated with the health of workers who work remotely were grouped into 5 categories: 1) Physical activity, 2) Psychological risk factors, 3) Musculoskeletal symptoms; 4) work productivity, academic, and fatigue; 5) comorbidities and sleep disturbance.

1) Physical activity

The establishment of restrictive measures and change of work modality during quarantine meant a decrease in physical activity (PA) associated with the use of electronic devices, even more so in young remote workers(31).

Particularly in diabetic patients with impaired glycemic control (±0.2% of the value of their last control), the PA level was reduced by 50.9%, associated with the transition to TR and the increase in hours due to the use of devices(32), showing an increase in sedentary behavior and adoption of negative eating habits(24).

2) Psychological risk factors: Anxiety, depression, and perceived stress

The first days of adaptation to RT were characterized by a decrease in anxiety and depression in the workers(33). Subsequent findings showed that the search for balance between work responsibilities(34,35), family(26)transition, and decrease in PA(31), were factors associated with increased depression. 17.9% of the variance in this was attributed to the transition to TR(34), anxiety(31,34), feelings of loneliness(31), and feelings of sadness(31).

Additionally, difficulties in accessing basic needs, limitations for the development of TR (OR= 2.04; 1.25-3.33; 95% CI), and remote learning are considered predictive factors for increased anxiety moderate to severe(36).

In particular, the increase in parenteral stress in mothers who migrated to this modality was associated with a decrease in quality of life(23), and those who were displaced to work from home presented an increase from 1.9% to 14.7% in symptoms of anxiety(25). In addition, 23.3% of workers do not agree with being able to fulfill their work responsibility from the TR(35).

3) Musculoskeletal symptoms

The inadequate work environment at home, without ergonomic characteristics, determines the presence of musculoskeletal symptoms; in this sense, those who adopted the TR during quarantine presented greater intensity of pain from 1.9 to 2.3 (0-5 pts .), compared to those who did not adopt TR (p<0.001)37. In addition, being between 35 and 49 years old, BMI ≥ 30, being under stress, not following ergonomic recommendations, sitting for a long time, having insufficient PA, and teleworking or distance learning were associated with greater low back pain intensity37.

Finally, the presence of malaise and discomfort in this population, associated with a sedentary lifestyle, affects more areas, such as the neck, shoulders, wrists, back, and hips/thighs25.

4) Labor and academic productivity and fatigue

TR is considered a positive contributor, however, recent studies associate it with a decrease in self-perception, productivity satisfaction, and concern about the spread of the virus22, by employees38.

Likewise, Italian workers experienced a 39.2% decrease in satisfaction and 40.6% point to domestic distraction (housework and family care), as well as the lack of work interaction as the main disadvantages experienced during the period. TR39. Also, working from home increased the workload by an average of 3 hours a week (43-46 h/s)40, and 50.4% of faculty teachers reported that this load was associated with the presence of minor children 26. Additionally, they reported a loss of efficiency due to technical problems with online services40. Therefore, the work period was extended, generating a physical and mental overload for the worker, observing a drop in academic productivity of 3.3 points40.

Finally, the reality of the TR exceeds the territorial limits; however, the perception varies from country and context; an example of this is the population of Taiwan which reported less productivity compared to the North Americans (4.4± 1.2 h. vs. 5.2± 1.2 h .)38.

5) Comorbidities and sleep disturbance

Changes in routine were common, even more so in the initial stage of quarantine; in this same period, there was an increase in the consumption of alcohol and cigarettes, the percentage of people with high blood pressure and gastrointestinal problems increased by 1.5% and 2.5%, respectively25. On the other hand, glycemic control in patients with diabetes is a challenge for public health; those patients who adopted the RT saw their glucose control levels deteriorate, experiencing an increase in weight (0.04±1.6kg) compared to reports of the first months of the pandemic32.

Additionally, the average use of visual screens increased by 6.4 ± 2.9h/day. at 8.2 ± 3.4h/day (p < 0.05) pre and post-quarantine in remote workers is associated with changes in the sleep routine, in this way, a greater preference for sleeping and getting up later compared to the pre-quarantine period has been observed. -quarantine. In addition, greater sleep disorders were manifested; 19% of workers reported feeling excessively sleepy25. The summary of the findings and outcomes are reported inTable 1.

Table 2. Summary of main findings of the studies

| Author, year | Study design | Population | Country | Findings and associated outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ferdinando Toscano y col., 2020 | Transversal | 265 public and private sector employees 26-35 years old (42%), 63% were women | Italia | Remote worker stress, influenced by isolation, influences decreased productivity and perceived satisfaction, moderated by concern about the virus. |

| Christine A. Limbers y col.,2020 | Transversal | 200 mothers; 33.5 ± 6.3 years old. | EE. UU | The increase in parenteral stress in mothers undergoing RT was associated with a decrease in quality of life. |

| Cillian P. McDowell, y col.,2020 | Transversal analítico | 1,242 remote workers, 68.6% women, 25.8% (25-34 years). | EE. UU | The transition to TR was associated with an increase in the time and use of visual screens (laptop, computer, tablets) and seated time. |

| Piya Majumdar, y col.,2020 | Transversal analítico | 203 office workers, 33.1±7.11 years; 18.2% were women | India | Remote workers increased the use of electronic devices (8.2 ± 3.4 h/d.), seated time, depressive symptoms, musculoskeletal symptoms, sleep disturbance (p<0.001), and anxiety. |

| Bradley A Evanoff, J y col.,2020 | Transversal analítico | 4 131 remote workers (faculty, teachers, post-doctoral staff) | EE. UU | 50.4% of faculty teachers reported increased workload, fatigue and stress in those who changed their work modality (associated with the presence of children and elderly people in care). |

| André O Werneck, y col.,2020 | Transversal analítico | 38,353 adult participants, 9,068 (RT: inactive + high TV use + high computer use) | Brasil | Young workers present more unhealthy behaviors: physical inactivity, increased use of PC and TV, associated with: higher level of loneliness OR=1.71 (1.42-2.07), feeling of sadness OR=1.73 ( 1.42-2.10) and anxiety OR=1.78(1.46-2.17) 95% CI. |

| Author, year | Study Design | Poblation | Country | Findings and associated outcomes |

| Miyako Kishimoto y col.,2020 | Transversal analítico | 168 patients with diabetes grouped into: "D" impaired glycemic control, "I" improved glycemic control, "N" unchanged. 53% in TR. | Japan | The transition to TR was associated with a decrease in physical activity in: Group “D”: 50.9%, “I”: 40%, “N”: 35.3%. In addition to the deterioration of glucose level control and weight gain (0.04±1.6) compared to the first months of the pandemic. |

| Claudia Traunmüller y col.,2020 | Transversal | 4126 participants (1438 in RT) 38.7±13.4 years) | Austria | Remote workers reported lower averages for anxiety and depression (B=−1.31±0.57; B=−2.28±0.70) p<0.001, respectively, compared to workers under normal conditions. |

| Elisabet Alzueta, y col.,2020 | Transversal analítico | 6,882 participants, 58.8% women, mean age 42.3±13.9 years. | 59 countries | Sociodemographic characteristics, exposure, habits, including the transition to TR, and others, explain 17.9% and 21.5% of the variance in the levels of depression and anxiety, respectively. |

| Sergio Madero Gómez y col.,2020 | Transversal, exploratorio | 332 participants (58.7% were women) | México | Regarding the perception of the impact of COVID at work, 23.3% disagree with being able to cover labor responsibility from the TR and 21.4% do not have the conditions to do so. |

| Peter Šagát1. y col.,2020 | Transversal analítico | 463 participants; 44.1% were women, 35.6±9.8 years old. | Saudi Arabia | The subjects in TR presented greater pain from 1.9 to 2.3 (0-5 pts.), compared to those who did not adopt the TR (p<0.001). Being between 35-49 years old, BMI ≥ 30, stress, not following ergonomic recommendations, remaining seated, insufficient PA were associated with greater intensity of low back pain. |

| Author, year | Study Design | Population | Country | Findings and associated outcomes |

| Antimo Moretti y col.,2020 | Transversal | 56 workers, 56.9% women aged 46.7±11.3 years, 29.4% have minor children at home. | Italy | 38.1% reported low back pain, 50% a worsening of neck pain. 40.6% refer to domestic distraction and work interaction as the main disadvantages of TR. Workers with musculoskeletal pain report lower job satisfaction. |

| Hongyue Wu, y col.,2020 | Transversal | 200 participants (32% industry sector, 68% education sector). 22% women, 26.6% between 23-39 years. | EE. UU | Remote workers experienced lower productivity by 38%, in researchers (education) it fell by 3.28 points. The workload increased by 3h/s. The average weekly working hours was 40.1± 29.2 |

| Elaine Ruiz B y col.,2020 | transversal | 353 participants, 79% women, mean age: 21 years. | EE. UU | Difficulty in RT (OR = 2.04, 1.25-3.33, 95% CI) was identified as a predictor of moderate-severe anxiety. |

| Yuhsuan Chang, y col.,2020 | Transversal | 778 participants (407 USA, 371 Taiwan) 66.6% and 43% were women, respectively. 36.1% (20-29 years old, Taiwan); 37.1% (30-39 years, USA) | Taiwán EE. UU | The Taiwanese population reported less productivity during TR compared to the North American population (4.4±1.2 vs 5.3±1.2). |

DISCUSSION

The review presented findings associated with RT in the context of the pandemic due to SARS-CoV-2, which are in turn associated with other factors.

Difficulties working from home and the transition to remote learning were identified as significant predictors of moderate to severe anxiety36, fear and anguish generated by the morbid nature of the pandemic together with the inadequate quality of housing or working conditions23,25,37, could increase people's alertness and alter the perception of TR, attributing psychological risk factors to it.

Likewise, the closure of schools has forced parents to take care of their children and work in the same environment, which implies distributing school hours at home and work; this overlapping of activities amplifies psychosocial risks, such as perception of mental fatigue and labor19, if there is no structured work schedule37.

Both job perception and scientific productivity suffered declines, even more so in women40-42, as example the scientific productivity of manuscripts registered in SSRN (Social Science Research Network), which generated women experienced a drop of 13.2% in the first weeks of adopting TR, even more so in assistant professors(42). It is precisely women who have received the least guidance support from universities41; and if we compare, during the months of March and April, male researchers increased their number of publications in arXiv by 6.4% while women only 2.7% in the same period last year43,44.

Psychosocial risks are part of the adaptation to change and are more frequent when the worker has not been trained or provided with tools, which generates disadvantages that compromise their mental health23,25,31,34. Work fatigue, stress, anxiety, and depression must be approached from a multidisciplinary perspective, given their multicausal nature38.

On the other hand, the reduction in PA31, the increase in hours spent in front of electronic devices32, and the alteration in sleep quality are associated with musculoskeletal symptoms in the neck, wrists, and hands in these workers.37. These end up constituting a source for the acquisition of comorbidities or their increase, even more so if there is poor control of people with risk factors such as diabetes25, so monitoring and follow-up in this population is necessary45,46.

On the other hand, the perception of decreased productivity and job satisfaction during RT has decreased38,47; however, the perspective of it is different for the employee and employer. 66% of local companies consider that productivity has been maintained and has even increased during the TR, while employees think the opposite48.

This would be explained in three points: first, the lack of consistent policies in TR in which at least 73% of companies lack an implementation plan48. Second, and at a global level, the continuous challenge of combining work and home, even more so for women, applies to the academic world, where institutional policies reaffirm the role of the male worker and ignore the needs of female personnel as mothers and workers19,42. . Finally, leave decisions and labor participation, in which employees design their own solutions, with little or no support from the employer42.

Finally, the association of TR with productivity or experienced workload is debatable. The positive results are overshadowed by the findings in the context of the pandemic19,40associated with the period of isolation, quarantine, and social distancing, so to improve the findings, it is necessary to promote better management practices, self-management, skills in information technologies and investment in home workspaces49,50.

CONCLUSION

The identification and description of outcomes observed in the remote worker are of interest in the context of the pandemic. Outcomes such as a decrease in labor and academic productivity, the latter higher in the female sex, added to the increase in psychosocial risk factors, sleep disturbance, and increase in the use of visual screens, are jointly due to multiple factors such as context, work situation, family and health status, so intervention strategies should consider these aspects.

In addition, evaluating the change in the levels of physical activity and sedentary behavior, with greater concern in diabetic people, is essential since it represents a risk for the acquisition of comorbidities. Finally, it is necessary to provide assistance and education to the remote worker to reduce associated complications. Given the partial permanence of TR and teleworking, it is essential to extend occupational surveillance to these work modalities in order to safeguard and positively impact the worker's health and lifestyle.

REFERENCES

1. OIT. COVID-19 y el mundo del trabajo (COVID-19 y el mundo del trabajo) [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 Jan 21]. Available from: http://www.ilo.org/global/topics/coronavirus/lang--es/index.htm [ Links ]

2. Gobierno del Perú. Decreto de Urgencia N° 026-2020 | Gobierno del Perú [Internet]. 15 de marzo. 2020 [cited 2020 May 7]. Available from: https://www.gob.pe/institucion/presidencia/normas-legales/460471-026-2020 [ Links ]

3. Buitrago Botero DM, Buitrago Botero DM. Teletrabajo: una oportunidad en tiempos de crisis. Rev CES Derecho [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2022 Jan 29];11(1):1-2. Available from: http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2145-77192020000100001&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=es [ Links ]

4. Kramer A, Kramer KZ. The potential impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on occupational status, work from home, and occupational mobility. Vol. 119, Journal of Vocational Behavior. Academic Press Inc.; 2020. p. 103442. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0001879120300671 [ Links ]

5. Oakman J, Kinsman N, Stuckey R, Graham M, Weale V. A rapid review of mental and physical health effects of working at home: how do we optimise health? BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2020 Dec 1 [cited 2022 Jan 29];20(1):1-13. Available from: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-020-09875-z [ Links ]

6. Allen TD, Golden TD, Shockley KM. How effective is telecommuting? Assessing the status of our scientific findings. Psychol Sci Public Interes [Internet]. 2015 Jan 1 [cited 2020 Dec 1];16(2):40-68. Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1529100615593273 [ Links ]

7. Masuda AD, Holtschlag C, Nicklin JM. Why the availability of telecommuting matters: The effects of telecommuting on engagement via goal pursuit. Career Dev Int. 2017;22(2):200-19. Available from: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/CDI-05-2016-0064/full/html [ Links ]

8. Gajendran RS, Harrison DA. The Good, the Bad, and the Unknown About Telecommuting: Meta-Analysis of Psychological Mediators and Individual Consequences. J Appl Psychol. 2007 Nov;92(6):1524-41. Available from: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2007-16921-005 [ Links ]

9. Martin BH, MacDonnell R. Is telework effective for organizations?: A meta-analysis of empirical research on perceptions of telework and organizational outcomes. Manag Res Rev. 2012 Jun;35(7):602-16. Available from: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/01409171211238820/full/html [ Links ]

10. Casper WJ, Bordeaux C, Eby LT, Lockwood A, Lambert D. A review of research methods in IO/OB work-family research. J Appl Psychol. 2007 Jan;92(1):28-43. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17227149/ [ Links ]

11. Lunde L-K, Fløvik L, Christensen JO, Johannessen HA, Finne LB, Jørgensen IL, et al. The relationship between telework from home and employee health: a systematic review. BMC Public Heal 2022 221 [Internet]. 2022 Jan 7 [cited 2022 Jan 29];22(1):1-14. Available from: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-021-12481-2 [ Links ]

12. Kröll C, Doebler P, Nüesch S. Meta-analytic evidence of the effectiveness of stress management at work. Eur J Work Organ Psychol [Internet]. 2017 Sep 3 [cited 2020 Dec 1];26(5):677-93. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/1359432X.2017.1347157 [ Links ]

13. Golden TD, Veiga JF, Simsek Z. Telecommuting's differential impact on work-family conflict: Is there no place like home? J Appl Psychol. 2006 Nov;91(6):1340-50. Available from: https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2F0021-9010.91.6.1340 [ Links ]

14. Mesmer-Magnus JR, Viswesvaran C. How family-friendly work environments affect work/family conflict: A meta-analytic examination [Internet]. Vol. 27, Journal of Labor Research. Springer; 2006 [cited 2020 Dec 1]. p. 555-74. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12122-006-1020-1 [ Links ]

15. Hammer LB, Neal MB, Newsom JT, Brockwood KJ, Colton CL. A longitudinal study of the effects of dual-earner couples' utilization of family-friendly workplace supports on work and family outcomes. Vol. 90, Journal of Applied Psychology. 2005. p. 799-810. Available from: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2005-08269-017 [ Links ]

16. Allan Marques de Macêdo T, Lucas dos Santos Cabral E, Ricardo Silva Castro W, Carneiro de Souza Junior C, Florêncio da Costa Junior J, Martins Pedrosa F, et al. Ergonomics and telework: A systematic review. Work. 2020;66:777-88. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32925139/ [ Links ]

17. Salinas RR, Flores FH, Madrigal AZ. Repercusiones en la salud a causa del teletrabajo. Rev Medica Sinerg [Internet]. 2021 Feb 1 [cited 2022 Jan 29];6(2):e641-e641. Available from: https://revistamedicasinergia.com/index.php/rms/article/view/641 [ Links ]

18. Rodríguez-Nogueira Ó, Leirós-Rodríguez R, Alberto Benítez-Andrades J, José Álvarez-Álvarez M, Marqués-Sánchez P, Pinto-Carral A. Musculoskeletal Pain and Teleworking in Times of the COVID-19: Analysis of the Impact on the Workers at Two Spanish Universities. 2020; Available from: https://dx.doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18010031 [ Links ]

19. Venegas Tresierra CE, Leyva Pozo AC. LA FATIGA Y LA CARGA MENTAL EN LOS TELETRABAJADORES: A PROPÓSITO DEL DISTANCIAMIENTO SOCIAL. Rev Esp Salud Pública [Internet]. 94AD Nov [cited 2020 Nov 25];1-17. Available from: www.mscbs.es/resp [ Links ]

20. Sardeshmukh SR, Sharma D, Golden TD. Impact of telework on exhaustion and job engagement: A job demands and job resources model. New Technol Work Employ. 2012 Nov;27(3):193-207. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1468-005X.2012.00284.x [ Links ]

21. Kossek EE, Lautsch BA, Eaton SC. Telecommuting, control, and boundary management: Correlates of policy use and practice, job control, and work-family effectiveness. J Vocat Behav. 2006 Apr 1;68(2):347-67. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0001879105000898 [ Links ]

22. Toscano F, Zappalà S. Social isolation and stress as predictors of productivity perception and remote work satisfaction during the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of concern about the virus in a moderated double mediation. Sustain. 2020 Dec 1;12(23):1-14. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/12/23/9804 [ Links ]

23. Limbers CA, McCollum C, Greenwood E. Physical activity moderates the association between parenting stress and quality of life in working mothers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ment Health Phys Act. 2020 Oct 1;19:100358. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1755296620300429 [ Links ]

24. McDowell CP, Herring MP, Lansing J, Brower C, Meyer JD. Working From Home and Job Loss Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic Are Associated With Greater Time in Sedentary Behaviors. Front Public Heal. 2020 Nov 5;8. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2020.597619/full#:~:text=Conclusion%3A%20COVID%2D19%20related%20employment,is%20a%20public%20health%20concern. [ Links ]

25. Majumdar P, Biswas A, Sahu S. COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown: cause of sleep disruption, depression, somatic pain, and increased screen exposure of office workers and students of India. Chronobiol Int [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2020 Nov 21];1-10. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/07420528.2020.1786107 [ Links ]

26. Evanoff BA, Strickland JR, Dale AM, Hayibor L, Page E, Duncan JG, et al. Work-related and personal factors associated with mental well-being during the COVID-19 response: Survey of health care and other workers. J Med Internet Res [Internet]. 2020 Aug 1 [cited 2020 Dec 14];22(8). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32763891/ [ Links ]

27. Trougakos JP, Chawla N, McCarthy JM. Working in a Pandemic: Exploring the Impact of COVID-19 Health Anxiety on Work, Family, and Health Outcomes. J Appl Psychol [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2020 Dec 14];105(11). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32969707/ [ Links ]

28. Langlois E V., Straus SE, Antony J, King VJ, Tricco AC. Using rapid reviews to strengthen health policy and systems and progress towards universal health coverage. BMJ Glob Heal [Internet]. 2019 Feb 1 [cited 2022 Jan 29];4(1):e001178. Available from: https://gh.bmj.com/content/4/1/e001178 [ Links ]

29. COVID-19: cronología de la actuación de la OMS [Internet]. [cited 2021 Mar 20]. Available from: https://www.who.int/es/news/item/27-04-2020-who-timeline---covid-19 [ Links ]

30. Rayyan [Internet]. [cited 2021 Oct 18]. Available from: https://www.rayyan.ai/ [ Links ]

31. Werneck AO, Silva DR, Malta DC, Souza-Júnior PRB, Azevedo LO, Barros MBA, et al. Changes in the clustering of unhealthy movement behaviors during the COVID-19 quarantine and the association with mental health indicators among Brazilian adults. Transl Behav Med [Internet]. 2020 Oct 6 [cited 2020 Nov 22]; Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33021631/ [ Links ]

32. Kishimoto M, Ishikawa T, Odawara M. Behavioral changes in patients with diabetes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Diabetol Int [Internet]. 2020 Sep 30 [cited 2020 Nov 23];1:3. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13340-020-00467-1 [ Links ]

33. Traunmüller C, Stefitz R, Gaisbachgrabner K, Schwerdtfeger A. Psychological correlates of COVID-19 pandemic in the Austrian population. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2020 Sep 14 [cited 2020 Nov 24];20(1):1395. Available from: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-020-09489-5 [ Links ]

34. Alzueta E, Perrin P, Baker FC, Caffarra S, Ramos-Usuga D, Yuksel D, et al. How the COVID-19 pandemic has changed our lives: A study of psychological correlates across 59 countries. J Clin Psychol [Internet]. 2020 Oct 31 [cited 2020 Dec 14];jclp.23082. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/jclp.23082 [ Links ]

35. Madero Gómez S, Ortiz Mendoza OE, Ramírez J, Olivas-Luján MR. Stress and myths related to the COVID-19 pandemic's effects on remote work. Manag Res. 2020 Oct 5;18(4):401-20. Available from: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/MRJIAM-06-2020-1065/full/html [ Links ]

36. Ruiz E, DiFonte M, Musella K, Flannery-Schroeder E. THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN COVID-19 LIFE DISRUPTIONS AND ANXIETY SEVERITY. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry [Internet]. 2020 Oct [cited 2020 Nov 24];59(10):S257. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7567526/ [ Links ]

37. Šagát P, Bartík P, Prieto González P, Tohănean DI, Knjaz D. Impact of COVID-19Quarantine on Low Back Pain Intensity, Prevalence, and Associated Risk Factors among Adult Citizens Residing in Riyadh (Saudi Arabia): A Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Internet]. 2020 Oct 6 [cited 2020 Nov 21];17(19):7302. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/17/19/7302 [ Links ]

38. Chang Y, Chien C, Shen LF. Telecommuting during the coronavirus pandemic: Future time orientation as a mediator between proactive coping and perceived work productivity in two cultural samples. Pers Individ Dif [Internet]. 2021 Mar 1 [cited 2021 Feb 23];171:110508. Available from: www./pmc/articles/PMC7648512/ [ Links ]

39. Moretti A, Menna F, Aulicino M, Paoletta M, Liguori S, Iolascon G. Characterization of home working population during covid-19 emergency: A cross-sectional analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Sep 1;17(17):1-13. https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/17/17/6284 [ Links ]

40. Wu H, Chen Y. The impact of work from home (wfh) on workload and productivity in terms of different tasks and occupations. In: Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics). Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH; 2020. p. 693-706. Available from: https://www.springerprofessional.de/en/the-impact-of-work-from-home-wfh-on-workload-and-productivity-in/18421248 [ Links ]

41. Nash M, Churchill B. Caring during COVID-19: A gendered analysis of Australian university responses to managing remote working and caring responsibilities. Gender, Work Organ [Internet]. 2020 Sep 21 [cited 2020 Nov 25];27(5):833-46. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/gwao.12484 [ Links ]

42. Cui R, Ding H, Zhu F. Gender Inequality in Research Productivity During the COVID-19 Pandemic. 2020 [cited 2020 Nov 25]; Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_Science_Research_Network, [ Links ]

43. Minello A. The pandemic and the female academic. Nature. 2020 Apr 17.Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-01135-9 [ Links ]

44. Viglione G. Are women publishing less during the pandemic? Here's what the data say. Nature. 2020 May 1;581(7809):365-6. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-01294-9#:~:text=during%20the%20pandemic%3F-,Here's%20what%20the%20data%20say,projects%20than%20their%20male%20peers.&text=Quarantined%20with%20a%20six%2Dyear,during%20the%20COVID%2D19%20pandemic. [ Links ]

45. Bouziri H, Smith DRM, Smith DRM, Descatha A, Dab W, Jean K. Working from home in the time of COVID-19: How to best preserve occupational health? [Internet]. Vol. 77, Occupational and Environmental Medicine. BMJ Publishing Group; 2020 [cited 2020 Nov 21]. p. 509-10. Available from: https://oem.bmj.com/content/77/7/509 [ Links ]

46. Kniffin KM, Narayanan J, Anseel F, Antonakis J, Ashford SP, Bakker AB, et al. COVID-19 and the Workplace: Implications, Issues, and Insights for Future Research and Action. Am Psychol. 2020.Available from: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2020-58612-001 [ Links ]

47. Tavares, Isabel A. Telework and health effects review, anda a research framework proposal. MPRA Pap [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2022 Jan 29]; Available from: https://ideas.repec.org/p/pra/mprapa/71648.html [ Links ]

48. Estudio de Trabajo Remoto 2020 | Investigación ISIL [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 19]. Available from: https://investigacion.isil.pe/estudio-trabajo-remoto-2020/ [ Links ]

49. COVID-19, teleworking, and productivity | VOX, CEPR Policy Portal [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 24]. Available from: https://voxeu.org/article/covid-19-teleworking-and-productivity [ Links ]

50. Development O for E co-operation and. Productivity gains from teleworking in the post COVID-19 era: How can public policies make it happen? [Internet]. [cited 2020 Dec 14]. Available from: http://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/productivity-gains-from-teleworking-in-the-post-covid-19-era-a5d52e99/ [ Links ]

8Article published by the Journal of the faculty of Human Medicine of the Ricardo Palma University. It is an open access article, distributed under the terms of the Creatvie Commons license: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International, CC BY 4.0(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/1.0/), that allows non-commercial use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original work is duly cited. For commercial use, please contact revista.medicina@urp.edu.pe.

Received: March 15, 2022; Accepted: July 17, 2022

texto en

texto en