Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Revista de la Facultad de Medicina Humana

Print version ISSN 1814-5469On-line version ISSN 2308-0531

Rev. Fac. Med. Hum. vol.24 no.1 Lima Jan./Mar. 2024 Epub Mar 29, 2024

http://dx.doi.org/10.25176/rfmh.v24i1.6060

Original Article

Analysis of adverse drug reactions caused by antipsychotic drugs in a mexican health institute

1Department of Biological Systems, Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana Xochimilco Unity. Mexico City, Mexico.

2Institutional Center for Pharmacovigilance, Instituto Nacional de Psiquiatría Ramón de la Fuente Muñiz. Mexico City, Mexico.

3Department of Hospital Pharmacy, Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Respiratorias. Mexico City, Mexico.

Introduction:

Adverse Drug Reactions (ADR) are unwanted clinical or laboratory manifestations that are related to drug use. ADR are common and are associated with significant risk of morbidity, mortality and hospital admissions. Antipsychotics have a reduced therapeutic window, and have been related to the manifestation of a variety of ADR.

Objetive:

To evaluate the pattern of ADRs due to antipsychotic drugs detected in patients treated at the Ramón de la Fuente Muñiz National Institute of Psychiatry between December 2021 and May 2022.

Methods:

Observational, descriptive, prospective and cross-sectional study of a series of cases. The seriousness, severity, and quality of the information in the notification of the ADR were defined in accordance with NOM-220-SSA1-2016, Installation and Operation of Pharmacovigilance, while causality was determined using the Naranjo algorithm.

Results:

The incidence of ADRs was 59%, with one or more ADR detected in 52 of the 88 patients who were receiving antipsychotic treatment during the study period. Forty-five percent of the ADR had probable causality and 55% possible; only three ADR were classified as serious as they prolonged the hospital stay and endangered the patient's life.

Conclusions:

The ADR of the gastrointestinal and endocrine systems were the most incidental, with hyperprolactinemia being the most frequent. Olanzapine and clozapine were the medications that caused the most ADR. It is recommended to promote the culture of notification and follow-up of ADR caused by antipsychotic drugs.

Keywords: Adverse drug reactions; antipsychotic agents; seriousness; severity; causality (source: MeSH NLM)

Introduction

Medications are directly used to prevent and treat diseases. However, all medications can also cause harmful effects1. According to the World Health Organization, an adverse drug reaction (ADR) is "a harmful and unwanted reaction that occurs after the administration of a drug at doses commonly used in humans, to prevent, diagnose or treat a disease, or to modify any biological function"2. Although some ADRs are detected during clinical trials; others, in the post-marketing stage3. ADRs are a significant cause of morbidity and mortality, responsible for up to 6% of hospital admissions with an associated mortality of 2%, and represent a substantial financial burden for patients and health systems. Additionally, they affect the patient's quality of life, confidence in the healthcare system, and length of hospital stay4.

While some ADRs are unpredictable, many can be prevented with proper foresight and control5. Continuous and constant surveillance, through pharmacovigilance programs, has allowed the reporting of suspected ADRs to generate alerts and prevent or avoid greater harm caused by medications6. Unfortunately, underreporting and under-notification remain a key challenge, as it has been estimated that less than 5% of all ADRs are reported in routine practice. This limits the ability of systems to provide accurate incidence data5.

One group of medications that may be associated with a significant incidence of ADRs is antipsychotics7, due to their pharmacodynamics and direct effect on the delicate balance of neurotransmitters that control behavior and brain function8. Psychiatric disorders are chronic in nature and often require prolonged and continuous medication treatments, increasing the likelihood of an ADR occurring during their use. Monitoring and prevention are crucial to improving clinical practice, enhancing medication safety, and supporting public health programs9.

In Mexico, there is the Instituto Nacional de Psiquiatría Ramón de la Fuente Muñiz (INPRFM), which is a specialized health center of national and international reference that provides care to patients suffering from mental disorders10. It is a public sector institute that belongs to the Mexican Ministry of Health and provides outpatient medical consultations and hospitalization services to psychiatric patients over the age of 1311; it is one of the most important and representative health centers in the country. Given this, this study aimed to determine the pattern of ADRs due to antipsychotic drugs, detected at the INPRFM during the period from December 2021 to May 2022.

Materials and methods

2.1 Study Design

This is an observational, descriptive, cross-sectional case series study with prospective collection of ADR notification reports at the INPRFM. The study period was from December 1, 2021, to May 31, 2022.

2.2. Population and Sample

The population consisted of ADR notifications received at the Institutional Pharmacovigilance Center of the INPRFM. The sample consisted of ADR notifications due to antipsychotic drugs.

ADRs detected and reported in patients over 18 years of age, of either sex, and who were being treated with antipsychotic drugs were analyzed. The identity of the patients was protected. The sampling of ADRs was done for convenience considering all cases that occurred during the study period.

2.3. Data Evaluation

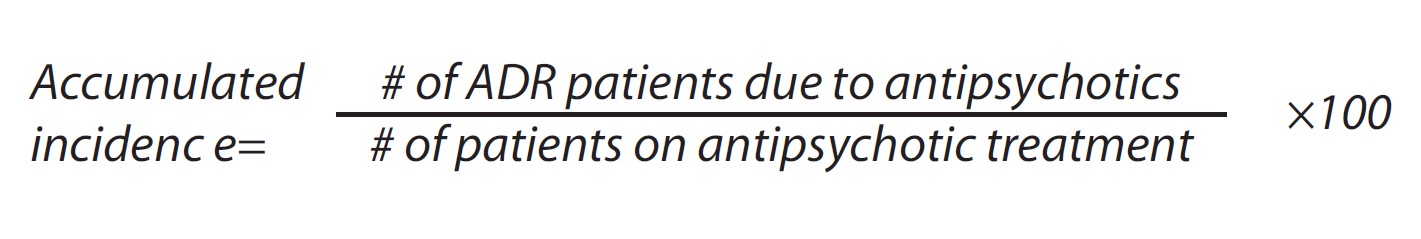

A description of the manifestation and type of problem caused and classified as ADR was made. The accumulated incidence of ADR occurrence during the study period was calculated using the following equation:

The severity of ADRs, defined according to NOM-220-SSA1-2016 "installation and operation of pharmacovigilance"12, was classified as "serious" and "not serious". According to the same standards, the severity of ADRs was classified as mild, moderate, and severe. On the other hand, the quality of the information from the ADR notification was also evaluated according to the same standards as grade 0 when the notification only includes the identified patient, at least one suspected adverse reaction, the suspected drug, and the notifier's data. Grade 1 when, in addition, it includes the dates of the start of the suspected adverse reaction, as well as the start and end of the treatment: day, month, and year. Grade 2 when it also includes the generic and distinctive name of the medication used, its posology, the route of administration, the reason for its prescription, the consequence of the event, and the data from the medical history. And grade 3 when, in addition, it includes the reappearance of the clinical manifestation consequent to a new administration of the drug in question.

Finally, the causality of ADRs was determined using the Naranjo algorithm and were also classified according to NOM-220-SSA1-201612as: 1) Certain when the clinical event manifested with a plausible temporal sequence in relation to drug administration, and could not be explained by concurrent disease, nor by other drugs or substances. The response to drug withdrawal (discontinuation) must have been clinically plausible. The event must have been definitive from a pharmacological or phenomenological point of view, using, if necessary, a conclusive re-exposure procedure. 2) Probable when the event manifested with a reasonable temporal sequence in relation to drug administration; it was unlikely to be attributed to concurrent disease, nor to other drugs or substances, and withdrawing the drug, a clinically reasonable response occurred. Information about drug re-exposure was not required. 3) Possible when the event manifested with a reasonable temporal sequence in relation to drug administration, but could also be explained by concurrent disease, or by other drugs or substances. Information regarding drug withdrawal may have been missing or unclear. 4) Improbable when the event manifested with an improbable temporal sequence in relation to drug administration, and could be explained more plausibly by concurrent disease, or by other drugs or substances. 5) Conditional to a clinical event, reported as an adverse reaction, for which it was essential to obtain more data for a proper assessment, or additional data were under examination. And 6) Not assessable to a notification that suggested an adverse reaction but could not be judged, as the information was insufficient or contradictory, and could not be verified or completed in its data.

Results

A total of 74 ADRs were detected during the study period, presented in 52 patients out of a total of 88 who were being treated with antipsychotics. The accumulated incidence of ADRs in the analyzed population during the study period was 59%. The average number of ADRs per patient was 1.42 (range 1-5). The detected ADRs were mostly in women (54%) and in the adult population between 30 and 59 years old. Also, most of the ADRs were detected in patients diagnosed with schizophrenia (65%). Table 1 shows these results.

Table 1: Description of patients who presented ADRs (Adverse Drug Reactions)

| Variable | Patients with at least 1 ADR (n = 52) |

| Number of ADRs per patient | |

| 1 | 36 (69%) |

| 2 | 12 (23%) |

| 3 | 3 (6%) |

| 4 | 0 (0%) |

| 5 | 1 (2%) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 24 (46%) |

| Female | 28 (54%) |

| Age group (years), n (%) | |

| Young (18-29) | 16 (31%) |

| Adults (30-59) | 28 (54%) |

| Elderly (>60) | 8 (15%) |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | |

| Schizophrenia | 34 (65%) |

| Psychosis | 9 (17%) |

| Bipolar disorder | 7 (14%) |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | 2 (4%) |

The 74 ADRs were caused by 24 different types: Olanzapine, risperidone, clozapine, aripiprazole, haloperidol, quetiapine, and paliperidone were the drugs that caused the detected ADRs (Table 2).

Table 2: Number of cases and type of ADRs caused by antipsychotic medications

| N° | ADR | Olanzapine | Risperidone | Clozapine | Aripiprazole | Haloperidol | Quetiapine | Paliperidone | Total |

| 1 | Hyperprolactinemia | 5 | 9 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 25 |

| 2 | Drowsiness | 4 | 1 | - | - | 1 | 2 | 1 | 9 |

| 3 | Sialorrhea | - | - | 4 | - | - | - | 1 | 5 |

| 4 | Weight gain | 5 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 5 |

| 5 | Alteration in the menstrual cycle | - | 1 | 2 | - | - | - | - | 3 |

| 6 | Parkinsonism | - | 2 | - | 1 | - | - | - | 3 |

| 7 | Insomnia | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | 2 |

| 8 | Dizziness | - | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | 2 |

| 9 | Akathisia | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | 2 |

| 10 | Sedation | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | 2 |

| 11 | Oculogyric crisis | - | - | - | 2 | - | - | - | 2 |

| 12 | Muscle stiffness | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2 | 2 |

| 13 | Palpitations | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | 1 |

| 14 | Hypotension | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| 15 | Bradycardia | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| 16 | Dysphagia | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| 17 | Headache | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 |

| 18 | Stress | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 |

| 19 | Mastalgia | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| 20 | Mastitis | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| 21 | Galactorrhea | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| 22 | Amenorrhea | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| 23 | Extrapyramidal symptoms | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| 24 | Hypoprolactinemia | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1 |

| Total | 19 | 17 | 11 | 9 | 8 | 5 | 5 | 74 | |

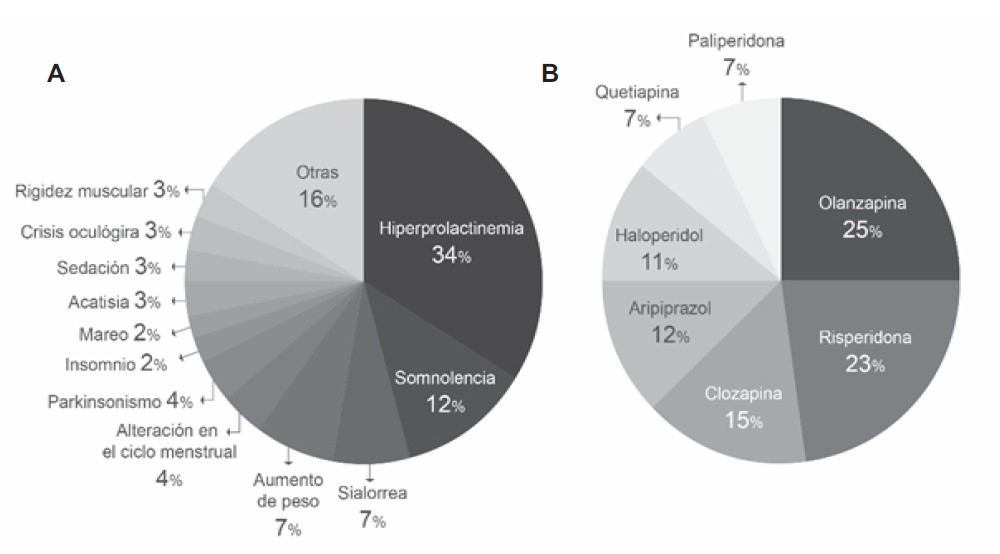

Figure 1-A shows the percentage distribution of antipsychotic-associated ADRs detected. It can be seen that the most frequent were hyperprolactinemia (34%), somnolence (12%), weight gain (7%), and sialorrhea (7%). On the other hand, olanzapine (25%), risperidone (23%), and clozapine (15%) were the drugs that caused the most ADRs (Figure 1-B ).

Figure 1. A: Percentage distribution by type of ADR detected in the study period. B: Percentage distribution of ADRs detected by suspected antipsychotic medication during the study period.

Table 3 shows that of the 74 ADRs found, none were severe in intensity and the majority were mild in severity (55%). Only 3 ADRs: hypotension, bradycardia, and sedation were classified as serious, which occurred in the same patient, and olanzapine was the suspected drug. In all cases, the quality of the information was at least grade 2. When analyzing the causality of ADRs using the Naranjo algorithm, 55% were of possible causality and 45% of probable causality.

Table 3: Description of identified ADRs

| Variable | ADR (n=74) |

| Severity, n (%) | |

| Mild | 55 (74%) |

| Moderate | 19 (26%) |

| Severe | 0 (0%) |

| Seriousness, n (%) | |

| Serious | 3 (4%) |

| Not serious | 71 (96%) |

| Quality of information, n (%) | |

| Grade 1 | 0 (0%) |

| Grade 2 | 41 (55%) |

| Grade 3 | 33 (45%) |

| Causality, n (%) | |

| Certain | 0 (0%) |

| Probable | 33 (45%) |

| Possible | 41 (55%) |

| Improbable | 0 (0%) |

| Conditional | 0 (0%) |

| Not assessable | 0 (0%) |

| Etiology, n (%) | |

| Dose increase | 6 (8%) |

| Change in route of administration | 1 (1%) |

| Unknown | 67 (91%) |

The factors associated with ADRs were unknown in 91% of cases; only in seven cases was it possible to know this information, six being of etiology due to dose increase and one due to a change in the route of administration.

Discussion

This study provides current information on ADRs associated with antipsychotics, a group of drugs related to various adverse reactions, detected in the Mexican population attended at one of Mexico's most important and reference health centers, where people from various parts of the country come. We found that olanzapine was the drug responsible for most of the detected ADRs, and hyperprolactinemia was the most incident.

The incidence of ADRs found during the analysis period was 59%, which is higher than what was observed in a study conducted at the CAISAME Long Stay Department, the largest hospital in the western region of Mexico, where 29.2% of the patients presented at least one ADR, 17.8% presented extrapyramidal effects, 15% non-extrapyramidal effects, and 3.57% both types of side effects. Although in said study a larger number of patients were analyzed (n = 140), the analysis period was shorter than the one used in our study13, which may explain why the accumulated incidence of ADRs was higher in the present work. In the same trend, the incidence of ADRs estimated in our study was also higher than that reported in other parts of the world; Lucca et al. reported, in 2014, an incidence of ~42% (n= 517 patients) over a two-year period9, while Chawla et al., in 2017, reported an incidence of ~17% (n= 224 patients) over a three-month period14. Both studies were conducted in India, which may explain the difference found, given that it is another geographical context.

Previously, it has been reported that ADRs in psychiatric patients are more frequent in women than in men15, and the data derived from our study do not differ from this observation. The group of people most affected by ADRs was adults between 30 and 59 years old, with an average age of 38 years; according to other reports, the higher incidence in this age group may be due to the onset of psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia and psychosis, which were the most prevalent diagnoses in our study; typically occur in early adulthood9, so it is expected that the prevalence of these disorders is high in adulthood.

Hyperprolactinemia was the most frequently detected ADR in the analyzed patients. In the literature, it has been estimated that it is induced in up to 70% of patients with schizophrenia who consume antipsychotics16. In our study, the incidence was 48%. Hyperprolactinemia caused by antipsychotics is due to blocking the dopaminergic D2 receptors, which in turn are responsible for inhibiting the hormone prolactin, which causes hyperprolactinemia17, which has short- and long-term consequences that can seriously affect the patient's quality of life, commonly causing menstrual disorders, sexual dysfunction, galactorrhea, amenorrhea, among others18. In addition, hyperprolactinemia can lead to other pathologies such as osteoporosis19. Therefore, pharmacovigilance programs are important within public institutions to propose risk management plans for antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinemia and its possible clinical implications.

On the other hand, the three drugs most frequently associated with the ADRs detected in the study were olanzapine, risperidone, and clozapine. This could be because olanzapine and risperidone were the most frequently used drugs in the clinical practice of schizophrenia at the INPRFM, a place that treated the most patients and where most ADRs were detected. This finding coincides, both in order and frequency, with the results of the study conducted by Piparva et al. regarding the suspected drugs related to antipsychotic ADRs20and with the publication of Prajapati et al. in 2013, who found clozapine and risperidone among the three main drugs that caused the most appearance of ADRs21.

On the other hand, regarding the characteristics of the ADRs found, all were mild or moderate in intensity, and it was not necessary to withdraw the suspected antipsychotic drug or change the treatment. However, the cases of hypotension, bradycardia, and sedation detected were considered serious, as they prolonged hospital stay and endangered the patient's life. Continuous monitoring and timely detection of all ADRs are important, as rare or infrequent ADRs can be identified22, and for those that are already known, the manifestation from patient to patient can be variable23. Chawla et al. reported, in 2017, the analysis of ADRs associated with antipsychotic drugs and observed that the causality of all ADRs analyzed using the Naranjo algorithm was classified as possible and probable14; we obtained similar results, as all the ADRs detected were classified in the same causality categories and no definite causality was identified.

It is important to note that all the cases of ADRs found had an information quality classification above grade 1 and have sufficient information about the patient, the drug, the start date of the suspicion and the treatment used and, for the cases classified with grade 3, data on re-exposure to the suspected drug, complying with international and national recommendations for ADR notifications.

Conclusion

This study provides additional information to that currently existing on the incidence and frequencies of ADRs of antipsychotic drugs in Mexico.

In general, a high incidence of ADRs was found in patients treated at the INPRFM, over 50%, most of them found in schizophrenic patients. Most were mild in severity. ADRs of the gastrointestinal and endocrine systems were the most incident, due to the use of atypical antipsychotic drugs. Olanzapine and clozapine were the drugs that caused the most ADRs. The most frequent gastrointestinal system ADRs were sialorrhea and weight gain, while in the endocrine system it was hyperprolactinemia. It is necessary to give importance to the monitoring of hyperprolactinemia, since it was an ADR caused by all the antipsychotics analyzed in this study. A protocol should be implemented that clearly establishes the prolactin concentration, which should begin to be gradually suspended and, in a timely manner, the drug that is causing this ADR or switch to antipsychotics that do not cause an increase in prolactin in the blood: the so-called prolactin-sparing antipsychotics or consider the use of dopamine agonists. It is recommended to promote the culture of ADR reporting at the INPRFM, both expected and unexpected, and to strengthen the follow-up of ADRs caused by antipsychotic drugs.

Table 1: Association between Dilation and Insufficiency of the Great and Small Saphenous Veins

| Insufficient GSV n (%) | |||

| Dilated GSV | Yes | No | Total |

| Yes | 45 (33,1) | 0 (0,0) | 45 (33,1) |

| No | 28 (20,6) | 63 (46,3) | 91 (66,9) |

| Total | 73 (53,7) | 63 (46,3) | 136 (100,0) |

| Insufficient SSV n (%) | |||

| Dilated SSV | Sí | No | Total |

| Yes | 5 (3,7) | 6 (4,4) | 11 (8,1) |

| No | 14 (10,3) | 111 (81,6) | 125 (91,9) |

| Total | 19 (14,0) | 117 (86,0) | 136 (100,0) |

GSV: Great Saphenous Vein, SSV: Small Saphenous Vein

The most frequent CEAP clinical class was C2, representing 44.9%, a group that mostly exhibited insufficiency in both the superficial and deep venous systems. See table 2.

Table 2: Association between Insufficient Venous System and CEAP Clinical Class

| Insufficient venous system | CEAP Clinical Class n (%) | |||||

| C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 | C6 | |

| Superficial | 6 (4,4) | 19 (14,0) | 5 (3,7) | 1 (0,7) | 1 (0,7) | 2 (1,5) |

| Deep | 4 (2,9) | 1 (0,7) | 0 (0,0) | 0 (0,0) | 0 (0,0) | 0 (0,0) |

| Perforating | 3 (2,2) | 2 (1,5) | 0 (0,0) | 0 (0,0) | 0 (0,0) | 0 (0,0) |

| Superficial and Deep | 3 (2,2) | 21 (15,4) | 0 (0,0) | 1 (0,7) | 1 (0,7) | 3 (2,2) |

| Superficial, Deep and Perforating | 1 (0,7) | 5 (3,7) | 0 (0,0) | 2 (1,5) | 2 (1,5) | 2 (1,5) |

| Superficial and Perforating | 2 (1,5) | 6 (4,4) | 0 (0,0) | 0 (0,0) | 0 (0,0) | 0 (0,0) |

| Deep and Perforating | 0 (0,0) | 2 (1,5) | 0 (0,0) | 0 (0,0) | 0 (0,0) | 1 (0,7) |

| None | 35 (25,7) | 5 (3,7) | 0 (0,0) | 0 (0,0) | 0 (0,0) | 0 (0,0) |

| Total | 54 (39,7) | 61 (44,9) | 5 (3,7) | 4 (2,9) | 4 (2,9) | 8 (5,9) |

C: Clinical Class (p-value ≤0.001, using the Monte Carlo test)

39.7% of all evaluated lower limbs were C1 (telangiectasias); 35.1% of them had an insufficient venous system. (See Table 3)

Table 3: Frequency of Insufficient Venous Systems in CEAP Clinical Class C1

| CEAP Clinical Class | Insufficient Venous System n (%) | |||||||

| Superficial | Deep | Perforating | Superficial and deep | Superficial, deep and perforating | Superficial and perforating | Deep and perforating | None | |

| C1 (n=54) | 6 (11,1) | 4 (7,4) | 3 (5,5) | 3 (5,5) | 1 (1,8) | 2 (3,7) | 0 (0,0) | 35 (64,8) |

In the saphenous veins, it was found that 44.1% of cases had insufficiency of the GSV; 3.7% of the SSV and 9.6% of both saphenous veins. In lower limbs with CEAP C2, half had GSV insufficiency. ( See Table 4)

Table 4: Association between Incompetent Segment of Saphenous Vein and CEAP Clinical Class

| Incompetent segment of saphenous vein | CEAP Clinical Class n (%) | |||||

| C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 | C6 | |

| GSV | 9 (11,5) | 39 (50,0) | 4 (5,1) | 3 (3,8) | 2 (2,6) | 3 (3,8) |

| SSV | 0 (0,0) | 4 (5,1) | 1 (1,3) | 0 (0,0) | 0 (0,0) | 0 (0,0) |

| GSV + SSV | 1 (1,3) | 6 (7,7) | 0 (0,0) | 1 (1,3) | 2 (2,6) | 3 (3,8) |

| Total (n=78) | 10 (12,8) | 49 (62,8) | 5 (6,4) | 4 (5,1) | 4 (5,1) | 6 (7,7) |

GSV: Great Saphenous Vein; SSV: Small Saphenous Vein; p-value = 0.227, using the Monte Carlo test

As shown in Table 5, there is a significant association between the CEAP clinical classification and the insufficiency of the SFJ, superficial and deep venous systems.

Table 5: Association between Insufficient Venous Systems and CEAP Clinical Classification

| Insufficient Venous System | CEAP Clinical Classification n (%) | p value | |||||

| C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 | C6 | ||

| SFJ | 2 (1,5) | 34 (25,0) | 4 (2,9) | 3 (2,2) | 3 (2,2) | 3 (2,2) | <0,001a |

| Superficial | 13 (9,6) | 51 (37,5) | 5 (3,7) | 4 (2,9) | 4 (2,9) | 7 (5,1) | <0,001a |

| Deep | 8 (5,9) | 29 (21,3) | 0 (0,0) | 3 (2,2) | 3 (2,2) | 6 (4,4) | <0,001a |

| Perforating | 7 (5,1) | 15 (11,0) | 0 (0,0) | 2 (1,5) | 2 (1,5) | 3 (2,2) | 0,103a |

SFJ: Saphenofemoral Junction; p-value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant, using the Monte Carlo test.

Results

66.7% of lower limbs with mild-moderate CVDLL had great saphenous vein (GSV) insufficiency and 9.0% had insufficiency in both saphenous veins. 7.7% of lower limbs with severe CVDLL had insufficiency in both saphenous veins, with a p-value of 0.011 and assessed by the Monte Carlo test. 50.7% of lower limbs with mild-moderate CVDLL had superficial venous system insufficiency, with a p-value of 0.005 and assessed by the Chi-square test. 29.4% of lower limbs with mild-moderate CVDLL had saphenofemoral junction (SFJ) insufficiency, with a p-value of 0.073 and assessed by the Chi-square test. 27.2% of lower limbs with mild-moderate CVDLL had deep venous system insufficiency, with a p-value of 0.001 and assessed by the Chi-square test. 16.2% of lower limbs with mild-moderate CVDLL had perforating venous system insufficiency, with a p-value of 0.020 and assessed by the Monte Carlo test.

As shown in Table 6, ultrasound findings showed a significant association between severe CVDLL and deep venous system insufficiency.

Table 6: Association between Insufficient Venous System and Severe Chronic Venous Disease of Lower Limbs

| Insufficient Venous System | Odds ratio (95% CI)a | p-value |

| Superficial | 7,52 (0,79-71,64) | 0,079 |

| Deep | 6,04 (1,02-35,73) | 0,047 |

| Perforating | 3,72 (0,73-18,93) | 0,113 |

CI: Confidence Interval; p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant; the regression was bivariate logistic.

Discussion

This study demonstrated the predominance of the female gender in CVDLL, consistent with other authors5,17,23. The superficial venous system was the most frequently insufficient system; GSV was the most affected, similar to Taengsakul5; GSV reflux was the most common in their study population. Andaç N et al.18observed that the most common segment of GSV with reflux was above the knee. Kanchanabat et al.19noted that although GSV reflux was present in most patients with lower limb CVI, SSV reflux could occur in a third of patients, especially those with lateral ulceration.

In this study, all dilated GSV and nearly half of the dilated SSV were insufficient, consistent with Choi et al.(24), who found that GSV and SSV diameters were significantly larger in patients with reflux, concluding that although vein diameter cannot be used as an absolute reference for venous reflux, it may have predictive value in patients with varicose veins. Kim et al.12reported that this relationship was only evident in the lower part of the thigh; Yang et al.9found that mean GSV diameters correlated with CEAP progression, but with SSV, the disease progression was less clear. In this study, the most common clinical category was C2: 44.8%, which aligns with Taengsakul5at 39%, unlike Porciunculla et al.7, who found C3 as the most frequent category at 60%.

It was found that a third of the CEAP clinical class C1 had venous system insufficiency, of which 12.8% was of the saphenous veins, similar to Hong17, who found a 19.2% prevalence of saphenous vein incompetence in CEAP C1 limbs; additionally, a considerable number of limbs without varices had incompetent saphenous veins.

In this study, 44.1% of lower limbs had GSV insufficiency, 3.6% SSV, and 9.5% both, similar to Hong17, who reported 71% GSV reflux; 11.9% SSV reflux, and 17.1% both GSV and SSV; however, Kanchanabat et al.19reported 47.2% GSV reflux; 8.1% SSV reflux, and 25.6% both. Yilmaz et al.23reported that the most common reflux pattern in patients with GSV insufficiency involved the SFJ with competent malleolar region: 48.9%.

The study showed a relationship between SFJ incompetence and CEAP clinical class, unlike Porciunculla et al.7, who found no relationship, but Hong17did show the correlation between incompetent SFJ and the distribution of incompetent segments in the GSV.

This work found deep venous system insufficiency in 75.5% of mild-moderate grades, much higher than Taengsakul5: 57.8%. Hong17reported that among limbs with deep venous system insufficiency, 98% had popliteal vein insufficiency and 2% femoral vein insufficiency.

This study did not find an association between perforating venous system insufficiency and the CEAP clinical category. Tolu et al.6found that varicose veins of lower limbs were related to perforating vein insufficiency in 44.7% of cases and observed a significant relationship between increased diameter of the perforating vein and the presence of perforating vein insufficiency. Huang et al.20found that incompetent perforating veins are a significant risk factor for dermal pigmentation.

One of the limitations of the study was the lack of uniformity in the Doppler reports, which prevented the analysis of other data such as reflux velocity, etc. The strength was that each venous system and its relationship with the clinical category were studied. It is suggested to conduct research on lower limb venous insufficiency in the Peruvian population using other classification systems such as HASTI and the Venous Clinical Severity Score, which are used to assess severity, quantify progression, and treatment outcomes of patients with CVI2,9.

REFERENCES

1. Basile AO, Yahi A, Tatonetti NP. Artificial Intelligence for Drug Toxicity and Safety. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2019 [Acceso 05/05/2023];40(9):624-35. Disponible en: https://www.cell.com/trends/pharmacological-sciences/fulltext/S0165-6147(19)30142-7 [ Links ]

2. AMNAT. Glosario de Farmacovigilancia [Internet]. Argentina.gob.ar [Acceso 17/10/2023]. Disponible en: https://www.argentina.gob.ar/anmat/farmacovigilancia/glosario [ Links ]

3. Alomar M, Tawfiq AM, Hassan N, Palaian S. Post marketing surveillance of suspected adverse drug reactions through spontaneous reporting: current status, challenges and the future. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2020 [Acceso 21/03/2023];11:2042098620938595. Disponible en: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/2042098620938595 [ Links ]

4. Patton K, Borshoff DC. Adverse drug reactions. Anaesthesia. 2018 [Acceso 29/03/2023];73:76-84. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.14143 [ Links ]

5. Fossouo Tagne J, Yakob RA, Dang TH, Mcdonald R, Wickramasinghe N. Reporting, monitoring, and handling of adverse drug reactions in Australia: scoping review. JPH. 2023 [Acceso 29/03/2023];9:e40080. Disponible en: https://publichealth.jmir.org/2023/1/e40080 [ Links ]

6. Beninger P. Pharmacovigilance: An Overview. ClinTher. 2018 [Acceso 29/03/2023];40(12):1991-2004 Disponible en: https://www.clinicaltherapeutics.com/article/S0149-2918(18)30317-5/fulltext [ Links ]

7. Bangwal R, Bisht S, Saklani S, Garg S, Dhayani M. Psychotic disorders, definition, sign and symptoms, antipsychotic drugs, mechanism of action, pharmacokinetics & pharmacodynamics with side effects & adverse drug reactions: Updated systematic review article. JDDT. 2020 [Acceso 29/03/2023];10(1):163-172. Disponible en: https://jddtonline.info/index.php/jddt/article/view/3865 [ Links ]

8. Ambwani S, Dutta S, Mishra G, Lal H, Singh S, Charan J, et al. Adverse Drug Reactions Associated With Drugs Prescribed in Psychiatry: A Retrospective Descriptive Analysis in a Tertiary Care Hospital. 2021 [Acceso 29/03/2023];13(11):e19493. Disponible en: https://assets.cureus.com/uploads/original_article/pdf/74029/20211210-17355-1d4vjnu.pdf [ Links ]

9. Minjon L, Brozina I, Egberts TC, Heerdink ER, van den Ban E. Monitoring of adverse drug reaction-related parameters in children and adolescents treated with antipsychotic drugs in psychiatric outpatient clinics. Front Psychiatry. 2021 [Acceso 29/03/2023];12:640377. Disponible en: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.640377/full [ Links ]

10. FACMED. Instituto Nacional de Psiquiatría Ramón de la Fuente Muñiz [Internet]. Feria Stands [Acceso 17/10/2023]. Disponible en: http://www.ferialibrosalud.facmed.unam.mx/index.php/project/instituto-nacional-de-psiquiatria-ramon-de-la-fuente-muniz/ [ Links ]

11. INPRFM. Instituto Nacional de Psiquiatría [Internet]. INPRFM [Acceso 17/10/2023]. Disponible en: https://inprf.gob.mx/faqs.html [ Links ]

12. Secretaría de Salud. Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-220-SSA1-2016, Instalación y operación de la farmacovigilancia [Internet]. DOF [Acceso 16/02/2023]. Disponible en: https://dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5490830&fecha=19/07/2017#gsc.tab=0 [ Links ]

13. Carmona-Huerta J, Castiello-De Obeso S, Ramírez-Palomino J, Duran-Gutiérrez R, Cardona-Muller D, Grover-Paez F, et al. Polypharmacy in a hospitalized psychiatric population: Risk estimation and damage quantification. BMC Psychiatry. 2019 [Acceso 21/03/2023];19(1):1-10. Disponible en: https://bmcpsychiatry.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12888-019-2056-0 [ Links ]

14. Chawla S, Kumar S. Adverse drug reactions and their impact on quality of life in patients on antipsychotic therapy at a tertiary care center in Delhi. Indian J PsycholMed. 2017 [Acceso 29/03/2023];39(3):293-298. Disponible en: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.4103/0253-7176.207332 [ Links ]

15. Seeman MV. The pharmacodynamics of antipsychotic drugs in women and men. Front psychiatry. 2021 [Acceso 29/03/2023];12:468. Disponible en: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.650904/full?ref=damahealth.com [ Links ]

16. Ruljancic N, Bakliza A, Pisk SV, Geres N, Matic K, Ivezic E, et al. Antipsychotics-induced hyperprolactinemia and screening for macroprolactin. Biochem Medica [Internet]. 2021 [Acceso 29/03/2023];31(1):113-20. Disponible en: https://hrcak.srce.hr/252086 [ Links ]

17. Chanson P. Treatments of psychiatric disorders, hyperprolactinemia and dopamine agonists. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022 [Acceso 28/03/2023];36(6):101711. Disponible en: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1521690X22000987 [ Links ]

18. Lu Z, Sun Y, Zhang Y, Chen Y, Guo L, Liao Y, et al. Pharmacological treatment strategies for antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinemia: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Transl. Psychiatry. 2022 [Acceso 29/03/2023];12(1):267. Disponible en: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41398-022-02027-4 [ Links ]

19. Chen H, Ye S, Zhang B, Xing H. A Case of Young Male Osteoporosis Secondary to Hyperprolactinemia. IJCMCR. 2022 [Acceso 29/03/2023];19(4):1-4. [ Links ]

20. Piparva KG, Buch JG, Chandrani KV. Analysis of adverse drug reactions of atypical antipsychotic drugs in psychiatry OPD. Indian journal of psychological medicine. 2011 [Acceso 29/03/2023];3(2):153-157. Disponible en: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.4103/0253-7176.92067 [ Links ]

21. Prajapati HK, Joshi ND, Trivedi HR, Parmar MC, Jadav SP, Parmar DM, et al. Adverse drug reaction monitoring in psychiatric outpatient department of a tertiary care hospital. Depression. 2013 [Acceso 29/03/2023];4(2):102-106. Disponible en: https://nicpd.ac.in/ojs-/index.php/njirm/article/view/2159 [ Links ]

22. Martin JH, Lucas C. Reporting adverse drug events to the Therapeutic Goods Administration. AustPrescr. 2021 [Acceso 21/03/2023];44(1):2-3. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7900275/ [ Links ]

23. Turner RM, Park BK, Pirmohamed M. Parsing interindividual drug variability: an emerging role for systems pharmacology. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Systems Biology and Medicine. 2015 [Acceso 21/03/2023];7(4):221-241. Disponible en: https://wires.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/wsbm.1302 [ Links ]

8 Article published by the Journal of the faculty of Human Medicine of the Ricardo Palma University. It is an open access article, distributed under the terms of the Creatvie Commons license: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International, CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/1.0/), that allows non-commercial use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original work is duly cited. For commercial use, please contact revista.medicina@urp.edu.pe.

Received: November 24, 2023; Accepted: February 18, 2024

text in

text in