Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista de la Facultad de Medicina Humana

versión impresa ISSN 1814-5469versión On-line ISSN 2308-0531

Rev. Fac. Med. Hum. vol.24 no.1 Lima ene./mar. 2024 Epub 29-Mar-2024

http://dx.doi.org/10.25176/rfmh.v24i1.6333

Review Article

Non-fatal strangulation/suffocation in context of gender violence: Medicolegal aspects and implications in clinical practice

1Department of Medical Specialties, Universidad de La Frontera. Temuco, Chile

2Universita Degli Studi di Verona, Italia.

3Department of Pathological Anatomy, Universidad de La Frontera. Temuco, Chile.

Despite the numerous efforts of the international community to eradicate all forms of violence against women, this problem is far from being resolved. According to the UN, one in three women has suffered physical or sexual violence from an intimate partner, sexual violence outside the couple, or both at least once in their life. Addressing this problem as a social health need of population groups allows an approach to gender violence as a collective health problem.

At the level of physical violence, strangulation/suffocation has been identified as one of the most lethal forms of domestic violence and sexual assault. Victims of domestic violence who have been choked or strangled are 7.5 times more likely to be killed by their partner. A victim of strangulation/suffocation can lose consciousness in seconds or die within minutes, days or weeks after the attack, as well as suffer permanent brain damage or disability or emotional trauma.

Recently, legal changes have been generated in the configuration of this crime, the penalties have increased in United Kingdom, the United States, Australia and New Zealand. The current non-systematic narrative review of literature sought to explore updated medico-legal aspects of non-fatal strangulation/suffocation in the context of gender violence, and are highlightedrelevant implications for clinical practice.

Keywords: Asphyxia; domestic violence; intimate partner violence; forensic medicine; physical examination (Source: MeSH).

INTRODUCTION

Gender equity, understood as the balanced recognition and valuation of the potential of women and men, the distribution of power between both, and its application, establishes the recognition of different realities, interests, and needs of women and men for the formulation of plans, programs, and interventions that aim at a differentiated and efficient impact, recognizing and working on social inequities. Despite numerous efforts by the international community to eradicate all forms of violence against women, this problem is far from being solved. According to the UN, it is estimated that one in three women has suffered physical or sexual violence by a partner, sexual violence outside the partnership, or both, at least once in their life1.

Violence against women, in the family context, can have physical, psychological, economic, and sexual aspects2. In the area of physical violence, strangulation has been identified as one of the most lethal forms of domestic violence and sexual aggression and has become one of the most accurate predictors of subsequent homicide in victims of intrafamily violence3,4.

Legal medical textbooks, usually, focus on the phenomenon of asphyxiation as a finding in necropsy, however, gender violence contexts hide many non-fatal cases that do not appear in official figures and that may eventually turn up at health centers, where staff should be able to detect and, eventually, formalize the corresponding complaint. Moreover, a particular group of victims may present even serious complications including the possibility of a deferred death5,6.

Internationally, the so-called non-fatal strangulation/suffocation (without resulting in death) is configured as any case in which a person intentionally strangles or suffocates another, including cases of intrafamily violence7-9. The legal approach to these types of aggressions led to changes in laws and associated penalties in the United Kingdom, United States, Australia, and New Zealand; defining it as a crime and increasing the severity of sanctions, including prison sentences7.

The purpose of this narrative, non-systematic literature review is to present updated medico-legal aspects of non-fatal strangulation/suffocation in the context of gender violence; highlighting those implications relevant for clinical practice.

Medico-Legal Aspects

The Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women was approved without a vote by the United Nations General Assembly with Resolution 48/104 on December 20, 1993, in which it was established as a violation of their rights and a factor of severity that affects health1. WHO estimates from 2018 reported that the lifetime prevalence of violence in women worldwide is 30%1.

Among the forms of physical violence against women, strangulation and suffocation present a high risk of lethality, and are associated with other forms of aggression10. It is described as a type of abuse associated with the pursuit of control and intimidation of the victim, over homicidal intent3,6,11,12, but, despite its intimidating nature, exposes victims 7.5 times more than the rest of the population to be murdered3.

Considering the varied meanings of the term suffocation, for the purposes of this review, we have considered it as mechanical asphyxiation by occlusion of the respiratory orifices13-15, which in the case of the law in the United Kingdom extends to "any action that affects the ability to breathe and is considered assault" towards the victim16. In contrast, strangulation corresponds to mechanical asphyxiation produced by compression of the neck by an active force exerted by hands, ligature, body parts, or another rigid object, which makes it difficult to adequately oxygenate the brain, mainly due to vascular occlusion3,13.

Plattner et al., in a retrospective case study, specifies the distribution of strangulation victims according to their type and demographic aspects. Regarding the type of strangulation, 82% of cases corresponded to manual strangulation, 16% by ligature, and 2% a combination of the previous ones. 97% of the victims were adults, predominantly between the ages of 20 and 30, and 3%, children. 85% of the victims are female, and 15%, male. All the male victims in this series were attacked by men. Of the women, only in two cases was a female aggressor suspected9.

The intensity of the sequelae or the death of the victim would be directly proportional to the time of exposure to oxygen deprivation and to the active force exerted, although these premises are based on case studies in fatal hangings captured by video3,17. One of these reviews is carried out by the Working Group on Human Asphyxia, in which it was observed that people lost consciousness within the first 10 seconds of vascular occlusion, the appearance of petechiae occurred within 30 seconds of venous occlusion, and they maintained movements and respiratory noises for around two minutes3, results similar to the study by Kabat in 194318. Even in people who have been released alive from the occluding element (in strangulation or in hanging), there may be a deferred death due to anoxic encephalopathy secondary to reduced cerebral blood flow5,17.

While research on gender violence in the last 30 years has favored advances in the typification of crimes against women, only a few countries have specific laws regarding non-fatal strangulation/suffocation. One of the initial major obstacles was to demonstrate its occurrence and to socialize the extreme form of violence it represents. Multiple initiatives with victim participation, such as "we can't consent to this" (a UK group whose volunteers seek to raise awareness of sexual violence) and the "Centre for Women's Justice" (a UK organization made up of lawyers and academics specializing in violence against women), have promoted studies, systematic reviews, and even legal advice. Their work has made it possible to visualize the neurophysiological impact of aggression on survivors of non-fatal strangulation episodes19.

Currently, this form of aggression is criminalized in countries such as the United States20, Australia, and the United Kingdom16. In the United Kingdom, the new Domestic Violence, Crime and Victims Act was enacted on June 7, 2022, which in its sections 75 A and 75 B typifies the crime of non-fatal strangulation/suffocation7,16,21, which is not limited to the results of the acts, but to the action itself of cervical compression or occlusion of respiratory orifices. With this, it is not required that the victim loses consciousness or has accentuated secondary damages for the crime to be configured7,16. Along with its new typification, sanctions were increased and differentiated from what was previously established in the context of bodily injuries. The new penalties range from one to five years of effective imprisonment, and compare with the previous payment of fines16,21. The population affected by this law is not only citizens within the territorial limits, but also people who carry the nationality and commit the criminal act abroad, as well as foreign residents and foreigners in transit within the territorial limits7,16,21. After its enactment, in 2022, the first detainee was on June 10, 20228and one of the first sentenced to prison was on October 27, 2022, with a sentence of 18 months. For the application of this legislative change, the Crown Prosecution Service developed guidelines for its lawyers to make proper use of these legal changes and how to direct the investigation7,22, similar to the guide issued by the California District Attorneys Association (CDAA). In the case of training and technical assistance for professionals involved in contexts of intrafamily violence, there are institutions such as the Training Institute on Strangulation Prevention20and The Family Justice Center Alliance, both from California, which, in addition to providing legal assistance to victims, are also research and training centers for professionals in both the legal and health fields. One achievement of these initiatives was that, step by step, the different states of the North American country ended up typifying non-fatal strangulation/suffocation as a serious crime in itself and not as a minor offense or misdemeanor9,23; Ohio was the last to include it in April 2023.

In Chilean medico-legal practice, non-fatal strangulation/suffocation is not specifically typified, but is included within the crimes of bodily injury. Under this concept, there may be an increase in its legal qualification, if it is carried out in the context of intrafamily violence24. Injuries are classified according to their severity, so the crime of injuries considers sentences that will depend on the result of the attack from one person to another, from a misdemeanor in the case of minor injuries to crimes with penalties of 10 years in case of mutilation or permanent damage. However, when injuries occur in the context of gender violence or intrafamily violence, it would constitute an aggravating factor, which implies risking a minimum penalty of 61 days of imprisonment, regardless of the magnitude of the injuries. The penalty could reach up to 15 years of imprisonment for the aggravating factor of injuries in the context of intrafamily violence. The scope of the norm is limited to crimes committed in the territory of the Republic by inhabitants and foreigners24.

Implications for Clinical Practice

Healthcare professionals may encounter patients who have suffered non-fatal strangulation/suffocation in various scenarios of their practice, including emergency services, whether because the victim spontaneously relates it, as a reason for consultation, or through the detection of suggestive physical signs. This medico-legal entity requires active suspicion to identify patients in danger, especially because cases without obvious external injuries can be treated6.

History and Physical Examination

Only 5% of strangulation victims seek medical attention within the first 48 hours after the assault; it is interpreted that they would seek help due to the appearance of some symptom4. When medical assistance is sought, symptoms such as neck pain25, hoarseness11,26, dysphagia3,11,19, headache11, breathing difficulties3,11,25,26, dizziness3,19, tinnitus19, and vision changes19,26are reported. It has also been described that patients can consult showing great emotional distress and anguish, which can cause medical teams to underestimate the reported aggression, biasing the consultation and attributing symptoms to a state of intoxication, hyperexcitation, and even substance abuse5,6,27. In traditional forensic pathology texts, it is common to find a section devoted to the so-called asphyxia syndrome and its possible causes, which are multiple, and whose classically described signs are petechiae, visceral congestion, pulmonary edema, cyanosis, and the controversial fluidity of the blood13-15. Likewise, these texts usually address strangulation and suffocation separately and mention the inconsistent presence of contusive lesions (ecchymosis, erosions, and excoriations) in a ligature or finger pattern on the neck and facial region. It should be noted that these classic signs are nonspecific by themselves for the diagnosis of the cause of asphyxia, so a correlation must be established with the study of the scene and the remaining background of the investigation3,13,17, in pursuit of making plausible diagnoses.

More specifically, and with special attention to non-fatal strangulation/suffocation, there are articles highlighting that 50% of the victims did not present visible cervical injuries at the time of examination5,6,27. In another series, it is reported that although 75% of the evaluated people were examined during the first 24 hours post-assault11, 35% of them presented injuries categorized as mild. Comparing the injuries described in reports of both surviving and deceased patients, it is described that in strangulation/suffocation, it is possible to recognize contusive injuries of similar characteristics and distribution, which may be added to cutaneous, conjunctival, and/or oropharyngeal mucosa petechiae3,5,6,11,25,26. Facial and/or cervical edema has also been described6,25,26. However, the physical examination may not present visible injuries because it clinically occurred with signs that disappear quickly, such as erythema or discrete edema28. Other findings described in the physical examination are contusions (ecchymosis, erosions, and wounds of the skin and lip mucosa, epistaxis, fracture of the hyoid and laryngeal structures, hoarse voice, nausea and vomiting, memory loss, consciousness compromise, seizures, incontinence of sphincters, facial paralysis or of extremities, swallowing disorder, tremor, hemianopsia, ptosis, ataxia, coma, or dissection of the carotid arteries5,6,11,19,25,26,28.

Complications that occur within the first 48 hours after the assault include aspiration pneumonia, laryngeal edema, pulmonary edema, ischemic stroke, hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, and death5,6,17,25,28.

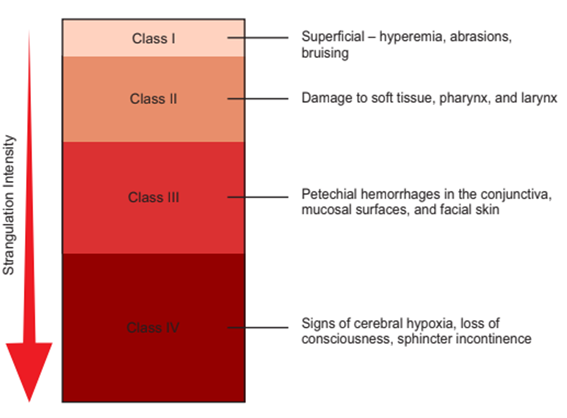

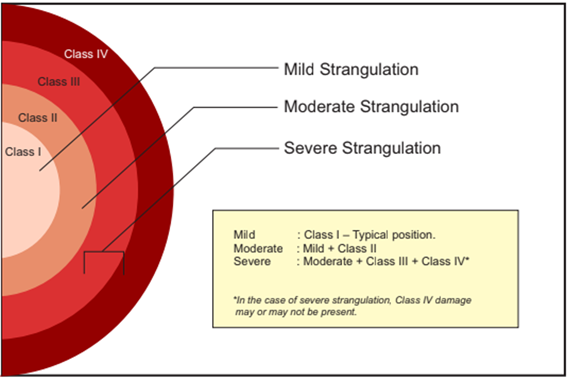

Plattner et al. propose the categorization of non-fatal strangulation and consider the severity and systematization of physical examination findings, on the condition that the complete medico-legal examination of the victim is carried out up to two days after the incident (Figures 1 and 2)25.

Additional Studies

Regarding additional studies, the reviewed publications suggest their implementation in symptomatic patients for the detection of injuries requiring specialty treatment:

Cervical radiography for the detection of fractures5,17,29.

Nasofibro-laryngoscopy to visualize petechiae of the laryngeal mucosa5,17,29.

Computed tomography of the brain5and/or neck3.

Magnetic resonance imaging of the neck5,26and/or brain26.

Carotid or vertebral artery angiography by computed tomography (CT Angio): described as the standard of reference for the evaluation of blood vessels26,29.

Carotid or vertebral artery angiography by magnetic resonance imaging (MRA)29.

Management

Regarding approach and follow-up, it is recommended as good practice to keep patients under observation for a period of time, not always specified, mainly due to the possibility of developing delayed complications such as cervical or laryngeal edema, due to their life-threatening risk5,17,26,28,30.

Considering the heterogeneous symptoms and signs, the possibility of immediate complications, and their potential rapid evolution, different reviews suggest that a detailed evaluation and documentation of external and internal injuries be carried out in cases of strangulation/suffocation, for a better understanding by the justice prosecuting bodies regarding the real magnitude of the aggression3,11. In this regard, the Faculty of Legal and Forensic Medicine of the Royal College of Physicians has issued at least two publications on the subject; also, it is mentioned to consider the evaluation of the patient by a specialist doctor in the presence of loss of consciousness, incontinence of sphincters, respiratory difficulty with decreased oxygen saturation, difficulty or inability to speak, presence of extensive ecchymosis, or subcutaneous cervical emphysema6,28. Additionally, it is recommended that, in suspected cases, along with the pertinent medical care, a clinical record that includes key or relevant points is made, which consider:

Complete record on the care sheet with description of positive and negative findings27.

Photographs of the neck (anterior, posterior, and lateral) of the initial external injuries, and their evolution if necessary, especially due to the risk of not being able to be verified in the following days6.

Performed imaging studies.

Consider the collection of evidence, such as subungual content6. It should be noted that health records, such as the medical record and/or emergency care forms, are legally relevant documents when it comes to investigating crimes that threaten the physical integrity and health of people and, sometimes, constitute the only evidence for judicial investigation3.

CONCLUSIONS

In the field of violence against women, which includes intrafamily and sexual violence, non-fatal strangulation/suffocation is a medico-legal entity that has gradually been recognized as a crime in the international context, given its prevalence and importance as a predictor of homicide. Efforts by academic, medical, judicial, and citizen bodies have enabled its visibility and socialization.

Healthcare personnel must maintain an expectant attitude in the context of gender violence, both oriented towards suspicion and the search for injuries that, at first glance, might go unnoticed, since, depending on the distribution and severity of the injuries associated with an episode of strangulation/suffocation, scenarios can range from the absence of visible injuries to death. In the spectrum of clinical presentations, a victim of strangulation/suffocation can lose consciousness in seconds or die in minutes, days, or weeks after the assault. This is due to associated injuries, complications of the respiratory system, or brain damage; to which is added the emotional impact on the victim.

Consequently, good practice involves active suspicion, possible hospitalization, adequate clinical records, and the performance of pertinent additional studies, as well as the presentation of a complaint to the relevant judicial authorities, always incorporating informed consent and confidentiality safeguards.

REFERENCES

1. OMS Organización Mundial de la Salud. Violencia contra las mujeres: estimaciones para 2018 [Internet]. 2021. Disponible en: https://www.who.int/es/publications/i/item/9789240026681. [ Links ]

2. Tipos de violencia | ONU Mujeres [Internet]. [citado 24 de julio de 2023]. Disponible en: https://www.unwomen.org/es/what-we-do/ending-violence-against-women/faqs/types-of-violence [ Links ]

3. Armstrong M, Strack GB. Recognition and documentation of strangulation crimes a review. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;142(9):891-7. [ Links ]

4. Strack GB, McClane GE, Hawley D. A review of 300 attempted strangulation cases part i: criminal legal issues. J Emerg Med. octubre de 2001;21(3):303-9. [ Links ]

5. McClane GE, Strack GB, Hawley D. A review of 300 attempted strangulation cases part II: Clinical evaluation of the surviving victim. Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2001;21(3):311-5. [ Links ]

6. Faculty of Forensic & Legal Medicine of The Royal Collegue of Physicians. Non-fatal strangulation in physical and sexual assault [Internet]. 2023 ene [citado 26 de junio de 2023]. Disponible en: https://fflm.ac.uk/resources/publications/non-fatal-strangulation-in-physical-and-sexual-assault/ [ Links ]

7. Kelly R, Ormerod D. Non-Fatal Strangulation and Suffocation. Criminal Law Review , 7 pp 532-555 (2021) [Internet]. 1 de julio de 2021 [citado 26 de junio de 2023]; Disponible en: https://www.sweetandmaxwell.co.uk/Product/Criminal-Law/Criminal-Law-Review/Journal/30791441 [ Links ]

8. Thomas H. Changes to Abuse Law for Non-Fatal Strangulation and Suffocation Offences | UK [Internet]. 2022 [citado 26 de julio de 2023]. Disponible en: https://www.simpsonmillar.co.uk/media/abuse-claims/changes-to-abuse-law-for-non-fatal-strangulation-and-suffocation-offences/ [ Links ]

9. Strangulation Legislation Chart - State Laws [Internet]. [citado 11 de noviembre de 2023]. Disponible en: https://www.familyjusticecenter.org/resources/strangulation-legislation-chart/ [ Links ]

10. Mittal M, Resch K, Nichols-Hadeed C, Thompson Stone J, Thevenet-Morrison K, Faurot C, et al. Examining Associations Between Strangulation and Depressive Symptoms in Women With Intimate Partner Violence Histories. Violence Vict. 1 de diciembre de 2018;33(6):1072-87. [ Links ]

11. Reckdenwald A, Powell KM, Martins TAW. Forensic documentation of non-fatal strangulation. J Forensic Sci. 1 de marzo de 2022;67(2):588-95. [ Links ]

12. Pritchard AJ, Reckdenwald A, Nordham C. Nonfatal Strangulation as Part of Domestic Violence: A Review of Research. Trauma Violence Abuse [Internet]. 30 de octubre de 2017;18(4):407-24. Disponible en: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1524838015622439 [ Links ]

13. Solano González É. Asfixias Mecánicas. Medicina Legal de Costa Rica. 2008;25(2). [ Links ]

14. Spitz WU. Asfixia. En: Spitz WU, Diaz FJ, editores. Spitz and Fisher's Medicolegal Investigation of Death: Guidelines for the Application of Pathology to Crime Investigation. 5th ed. Elsevier; 2005. [ Links ]

15. Villanueva Cañadas E. Asfixias mecánicas. En: Villanueva Cañadas E, editor. Gisbert Calabuig Medicina legal y toxicológica. 7a ed. Barcelona: Elsevier; 2019. [ Links ]

16. UK Government. Domestic Abuse Act 2021. Chapter 17. Part 6. UK Public General Acts [Internet]. 2021;1-86. Disponible en: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2021/17/enacted/data.pdf [ Links ]

17. Hawley DA, Mcclane GE, Strack GB. A review of 300 Attempted Strangulation Cases Part III : Injuries in Fatal Cases. Journal of emergency medicine. 2001;21(3):317-22. [ Links ]

18. Kabat H. Acute arrest of cerebral circulation in man. Arch Neurol Psychiatry [Internet]. 1 de noviembre de 1943;50(5):510. Disponible en: http://archneurpsyc.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?doi=10.1001/archneurpsyc.1943.02290230022002 [ Links ]

19. Bichard H, Byrne C, Saville CWN, Coetzer R. The neuropsychological outcomes of non-fatal strangulation in domestic and sexual violence: A systematic review. 2020. [ Links ]

20. California District Attorneys Association. Investigation and Prosecution of Strangulation Cases [Internet]. 2020. Disponible en: www.cdaa.org [ Links ]

21. Strangulation and suffocation - GOV.UK [Internet]. 2022 [citado 31 de enero de 2023]. Disponible en: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/domestic-abuse-bill-2020-factsheets/strangulation-and-suffocation [ Links ]

22. CPS publishes new guidance on non-fatal strangulation and suffocation laws | College of Policing [Internet]. 2022 [citado 16 de julio de 2023]. Disponible en: https://www.college.police.uk/article/cps-publishes-new-guidance-non-fatal-strangulation-and-suffocation-laws [ Links ]

23. There are still a few jurisdictions in the US where strangling someone is a misdemeanor | CNN [Internet]. [citado 11 de noviembre de 2023]. Disponible en: https://edition.cnn.com/2020/01/24/us/strangulation-felony-bills-dc-maryland-ohio-trnd/index.html [ Links ]

24. Ley Chile - Codigo PENAL 12-NOV-1874 MINISTERIO DE JUSTICIA - Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional [Internet]. 1874 [citado 26 de julio de 2023]. Disponible en: https://www.bcn.cl/leychile/navegar?idNorma=1984 [ Links ]

25. Plattner T, Bolliger S, Zollinger U. Forensic assessment of survived strangulation. Forensic Sci Int [Internet]. 29 de octubre de 2005 [citado 18 de julio de 2023];153(2-3):202-7. Disponible en: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0379073804006280?via%3Dihub [ Links ]

26. Dunn RJ, Sukhija K, Lopez RA. Strangulation Injuries [Internet]. StatPearls. 2023. Disponible en: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17961956 [ Links ]

27. Goverment of Western Australia Women And Newborn Health Service. Non-Fatal Strangulation ( NFS ) in the context of Intimate Partner Violence : A guide for clinicians. [ Links ]

28. Faculty of Forensic & Legal Medicine of The Royal Collegue of Physicians. Non-fatal strangulation: in physical and sexual assualt [Internet]. Faculty of Forensic & Legal Medicine. 2020 mar. Disponible en: www.fflm.ac.uk [ Links ]

29. Recommendations for the Medical/Radiographic Evaluation of Acute Adult Non/Near Fatal Strangulation [Internet]. [citado 18 de julio de 2023]. Disponible en: https://www.familyjusticecenter.org/resources/recommendations-for-the-medical-radiographic-evaluation-of-acute-adult-adolescent-non-near-fatal-strangulation/ [ Links ]

30. De Boos J. Non-fatal strangulation: Hidden injuries, hidden risks. Emergency Medicine Australasia. 19 de junio de 2019;31(3):302-8. [ Links ]

8 Article published by the Journal of the faculty of Human Medicine of the Ricardo Palma University. It is an open access article, distributed under the terms of the Creatvie Commons license: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International, CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/1.0/), that allows non-commercial use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original work is duly cited. For commercial use, please contact revista.medicina@urp.edu.pe.

Received: January 22, 2024; Accepted: February 08, 2024

texto en

texto en