1 Introduction

Evidentiality has recently become quite a discussed topic in linguistics and, on many occasions, its studies are considered controversial. Not all authors agree on what can be labelled as evidential and not all of them put forth that Romance languages exhibit evidentiality. On the one hand, Squartini (2001) establishes that the Romance languages described in Table 1 have an evidentiality system, because the morphological future (MF) and the conditional (COND) can convey inference and reportativity.

Table 1 Evidentiality in the Romance languages via MF and COND [I=inferential / R=reportative] (Squartini 2001)

| Portuguese | Spanish | French | Italian | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MF | I / R | I | I | I |

| COND | I / R | I / (R) | I / R | R |

On the other hand, Aikhenvald (2004) argues that, although every language has evidentiality strategies, since there are always ways to express the source of information of an utterance, evidentiality per se is an inflectional system that marks primarily, hegemonically or frequently source of information. This paradigm may also express other linguistic realities, but, for this author, the importance resides in the primary semantic value. Escandell (2014, 2022), for instance, defends that the meaning encoded by the MF, in Spanish, is better characterised as evidential; likewise, Lara (2021a) states that Peninsular Spanish has an evidential paradigm embodied in the MF and the COND: the former emerges for conjectures, while the latter can be useful for both conjectures referred to a past event and reportativity. Furthermore, Portuguese behaves the same, but its MF can also express reportativity, while Galician only exhibits a pattern of evidentiality through the MF (but not the COND). Catalan swings depending on its varieties, since the Valencian part has developed evidentiality via the MF, whereas Catalonia and the Balearic Islands lack evidentiality. The theory on which this author has based his conclusions is the one put forward by Aikhenvald (2004).

In addition to the research carried out for Romance varieties, evidentiality has been analysed in depth for Turkic languages (see Johanson 2018), Uralic and Altaic (see Skribnik, 1998; Skribnik and Kehayov, 2018), Tibetan and Mongolic (see Hill and Gawne 2017; Brosig and Skribnik, 2018; DeLancey 2018) or those from the North American area (see Thornes 2018). All these investigations have focused on the type of evidentiality they possess, the morphological origin of their evidential paradigm or to what extent the formation of this system is the result of language contact. However, there is no research that addresses the cause why which a given variety, at a given moment, creates an inflectional paradigm that expresses source of information. In other words, we do not know if the emergence of an evidential system (as Aikhenvald understands it) responds to some linguistic prerequisites, that prompt its formation within a specific place and time.

The analyses of Lara (2021a) indicate that the evidential morphological system of Spanish arises in the west of the Iberian Peninsula, and that it further spreads throughout the Spanish-speaking area as well as across its neighbouring Ibero-Romance languages. In another study, Lara (2021b) defends that Italian created its evidential paradigm from the southern varieties. Cross-linguistically, the investigations on evidentiality cover languages that, simultaneously, show an ergative or split ergative alignment and the same applies to the dialects of Spanish and Italian, where evidentiality is said to have emerged. At a vernacular level, they present several phenomena that can be considered as ergative tendencies.

In light of this simultaneity (ergative patterns and evidential paradigm), in this article, I intend to find whether this coincidence is only apparent or, in fact, there is a clear correlation between (split) ergativity and evidentiality. My hypothesis is based upon the idea that the existence of one is a consequence of the other and that, therefore, the arising of evidentality in Peninsular Spanish in the area where it did cannot be coincidental. The same can be said for Italian and for other languages that are not Romance or not even Indo-European. In order to verify the felicity of my hypothesis, I will now depict the behaviour of both evidentiality and ergativity, to later study the linguistic tendencies of Spanish, the Romance languages and other families. As a result, in 2, I will analyse the phenomenon of evidentiality in general terms; in 3, I will focus on studying ergativity or its split systems from a typological perspective; in 4, I will devote the analysis to arguing the motives for both ergativity and evidentiality to co-occur, and I will explain the three possible causes for evidentiality to appear in a given language; in 5, I will analyse the case of Spanish and the other Romance languages, while in 6, I will synthesise the conclusions.

2. Evidentiality

In the introduction, I remarked that evidentiality does not arouse consensus, since, depending on the author, the definition is broader or more restrictive. While, for Aikhenvald (2004), evidentiality is a morphological system that primarily, systematically or univocally marks source of information, Palmer (1986) holds that evidentiality may be any resource that conveys source of information, either through adverbs such as apparently, circumlocutions, modal verbs or the use of certain verb tenses that may connote inference or reportativity, even if such an use is secondary or sporadic. Tournade and LaPolla (2014) also support a much broader conception of evidentiality. In this article, I will endorse Aikhenvald’s (2004, 2018a) theses.

Although not every language has an inflectional system that refers to the source of information, those that have developed it do not exhibit a homogeneous pattern: either their paradigm is defective, arising for a certain temporality or grammatical person, or it is optional, or the marking of a type of information source prevails over everything else. Additionally, the morphological marking of evidentiality in a given language can be classified into different systems, depending on the number of types of source of information that can express: there are systems that discern between two options, three, four and, to a lesser extent, five or more. Nevertheless, in each of these subsystems there is certain coherence, since there is always a special interest in marking a piece of information that does not come from first-hand, such as reportativity. If the options multiply, the emphasis is not only applied to not first-hand information, but to the dichotomy between direct and indirect evidence: what one sees or hears versus what one infers, assumes, or concludes from one’s knowledge of the world or other mental processes.

The fact that there are languages that lack an evidentiality system does not mean that they cannot create one, since, as Aikhenvald (2004, 2018a) herself demonstrates, there are several processes that tend to turn a series of constituents into evidential morphemes, namely: grammaticalization of certain verbs, copulas, specific verbal tenses and moods, locative and deictic markers, and even evidential strategies that have become fossilised. This author claims that the MF and the COND are likely to be reanalysed as markers of evidentiality, exemplifying the COND in French (although she does not label this language as having evidentiality). Finally, Aikhenvald (2004, 2018b) also warns that evidentiality may be the result of language contact.

Despite the fact that the studies of this author are quite famous, no scholar who has dealt with evidentiality in the Romance languages has commented on the taxonomy of their paradigm, indicating whether the Romance languages have a system that distinguishes between two, three or more types of source of information. In any case, as I will defend below, the affirmations that have been made about the existence of evidentiality in the Romance spectrum, especially in French, do not fulfil the definition of evidentiality, as I understand it here.

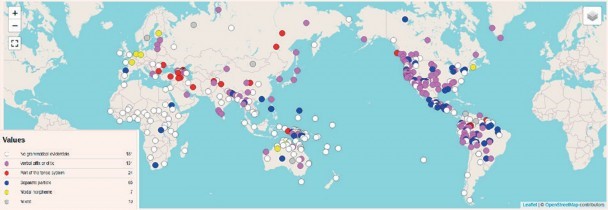

At the geolinguistic level, we count with several figures that try to graphically draw the extension of this phenomenon and its idiosyncrasy. Observe Figure 1.

Figure 1 shows that the codification of evidentiality in the languages of the world is conveyed through five fundamental strategies: verbal affixes (the most common), the reuse of a verbal tense (a strategy that occurs especially in the Balkans, the Middle East and Pacific areas), separate particles (the most frequent alternative after morphemes), modal morphemes (Finnish and Germanic languages, among others), and a mixture of the above. Likewise, the blank dots indicate that these languages do not have evidential morphological markers.

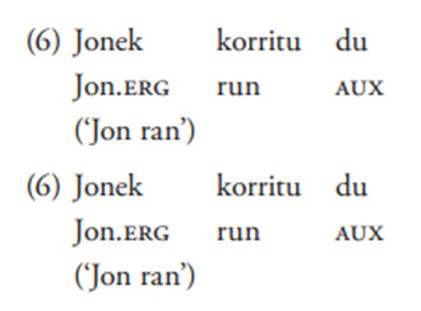

Figure 1 presents several problems. The first of them is to encompass modal verbs as mood morphemes. According to De Haan (2013), sentences such as (1-3) from Dutch, German and French (taken from his work), respectively, exhibit a morphological strategy of evidentiality by means of the modal verb, while sentences (4 -5) of English and Spanish, respectively, are not considered as morphological strategies of evidentiality, despite presenting exactly the same alternative and the same verb.

The second problem is precisely the contradiction that I have just highlighted, since the same modal verbs constitute a proof of the existence of evidentiality in certain languages, but not in others. In addition, although De Haan (2013) applies a much broader perspective in his conception of evidentiality, he does not underpin what Squartini (2001) defends for Romance languages, since the former does not understand that Spanish has evidentiality (Italian and Portuguese are not even included in the sample), but the latter puts forth just the opposite. Lastly, the very distribution of the strategies contravenes what has been analysed by other authors: De Haan (2013) states that French expresses evidentiality through modal verbs, while Squartini (2001) insists that it is the verb tenses (specifically, the MF and the COND) the means for such a possibility.

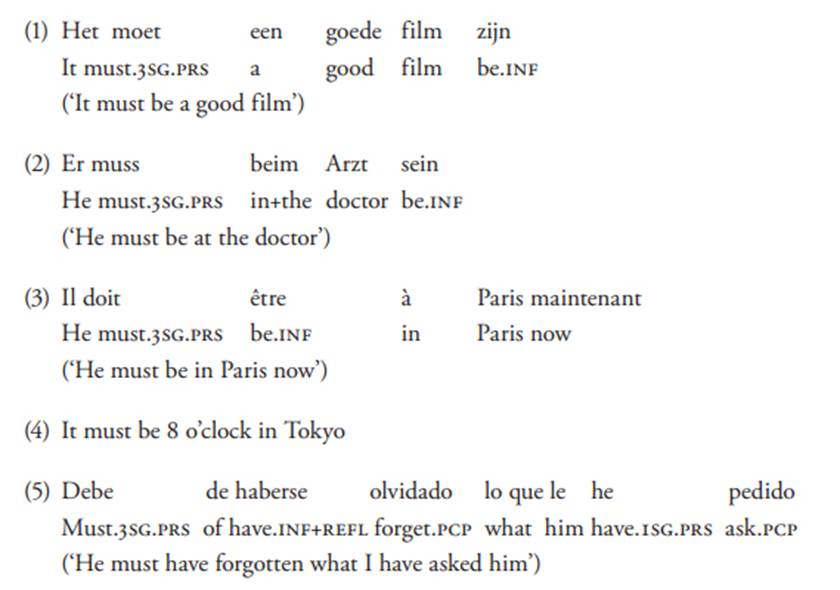

In spite of the problems that, in my opinion, Figure 1 poses, the cartographic distribution is virtually the same as the one provided by Aikhenvald (2004), reproduced on Figure 2.

Figure 2 shows that evidentiality systems, as conceived by this author, that is, morphological paradigms that frequently mark source of information (regardless of the fact that they may also express other values), diffuse throughout the Caucasus, Central Asia, part of Pacific Asia, the interior of North America and the Amazon area of South America. Also, there are isolated regions of evidentiality within Australia, as well as around the Gulf of Guinea and the area between the Amazonia and the Southern Cone. The comparison of Figures 1 and 2 suggests that evidentiality does not occur in all languages, although it is likely to do so. Similarly, the inconsistencies between both Figures once again highlight the lack of unanimity in scholars for labelling evidentiality, but these dissensions are not an obstacle to verifying that this phenomenon spreads through the Turkic, Finno-Uralic, Altaic, Tibetan and Mongolic languages, as well as throughout other non-IndoEuropean families in North America, the Amazonia, Southeast Asia, Australia, and in Basque. As a matter of fact, the biggest controversy to this respect affects the Romance languages.

3. Ergativity

Ergativity is understood as the differential marking of the subject of a transitive (A) as opposed to that of the subject of an intransitive (S) and the object of a transitive (O), both of which receive the same marker (Dixon, 1994). In other words, ergativity promotes the trait of agency (almost always embodied in a human entity), volition or control, compared to other semantic parameters. However, ergative languages tend to head towards nominative-accusative models, presenting an intermediate phase in which they exhibit behaviours of both options. Dixon (1994) affirms the low probability of finding purely ergative or purely nominative languages and the relative frequency of finding languages with a split pattern.

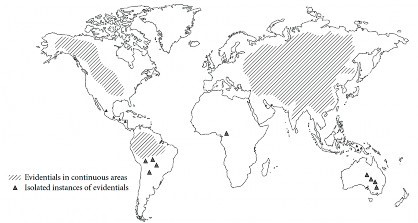

Basque, without going any further, is usually classified as an ergative-absolutive language, but the configuration of its arguments prompts the split based on the features of control, volition, animacy or agency (see 6-7, by Hualde and Ortiz de Urbina, 2003).

Occurrences (6-7) demonstrate the distinguishing treatment of the subject of an intransitive verb, highlighting the split based on the abovementioned semantic features. In (6), the subject is inflected in ergative because the event of running is usually volitional, controlled and agentive, while (7) selects an absolutive subject because the event of leaving does not necessarily imply these factors. In other words, Basque differentiates between unergatives and unaccusatives in case marking.

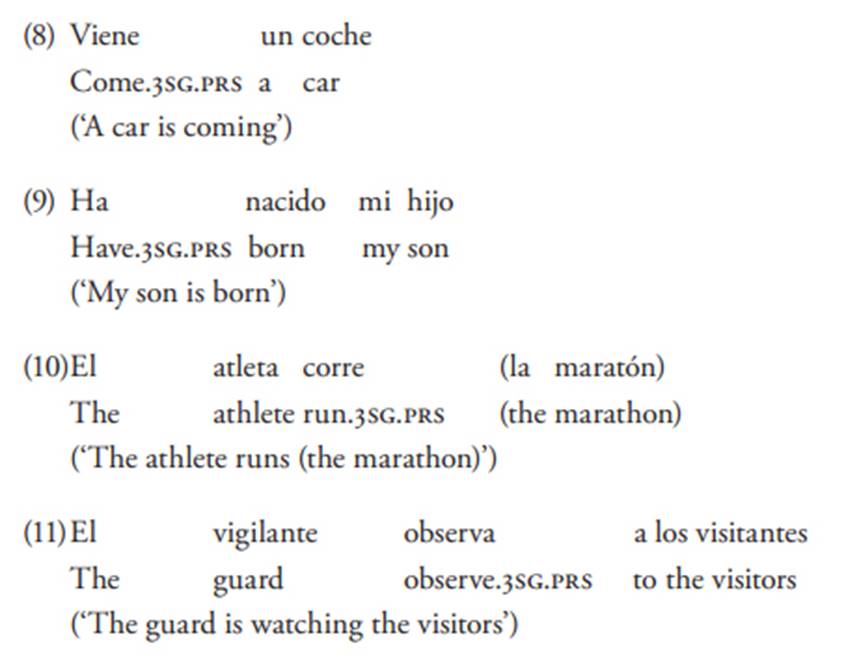

Ergativity has traditionally been associated with a purely morphological behaviour, but the literature has broadened its definition, underlying the fact that syntax can also respond to volitional, controllable or agentive features. For instance, McGregor (2009) makes sure that ergativity can materialise not only through inflectional morphology in the verb, noun or pronoun, but also through the order of constituents. For him, an ergative pattern is one that gathers the patient and the author under the same behaviour, unlike the agent, which receives another kind of treatment. In this sense, an ergative pattern can be word order, specifically that of the arguments in intransitive and transitive verbs, since the grammatical subject of the unaccusative (patient) usually behaves like the object of a transitive; instead, the agent of a transitive is usually the same as the agent of an intransitive (8-11).

In (8-9), the syntactic subjects of coming and being born are often placed in a prototypical object position, due to their lack of volition, agency or control. However, although (10) is also intransitive, regardless of its unergative or transitive version, the syntactic subject coincides with the semantic, so its unmarked position comes always before the verb, as occurs with the subject of the transitive in (11).

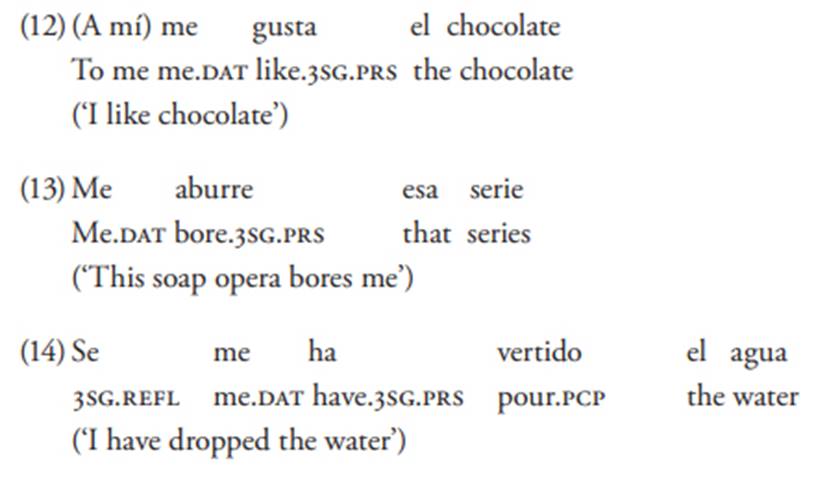

McGregor (2009) goes even further and postulates what he calls discursive ergativity. This implies the systematic presentation of the author or the patient at the beginning of the sentence as a synonym of new information, contrary to the agent, which is usually interpreted as known information (12-14).

Sentences (12-14) reflect what McGregor (2009) has called discursive ergativity, since in all of them, the patient, the experiencer and the author (not the agent) of the action has been positioned at the very beginning of the discourse, because they are human entities. In all these cases, the syntactic subject is in a position prototypically held by the object and, although (12-13) shows an experiencer and even a patient, (14) promotes me as the author of the event of pouring in order to establish a distinction with the semantic role of the agent. While the agent implies volition, the author conveys an unwilling event it has brought about (Givón, 2001).

The previous examples also certify the use of the dative for all these thematic roles, which is not trivial. This grammatical case usually presents high topicality, since it frequently embodies a human entity. This feature is also behind another ergative pattern, called dative subject. I will focus on dative subjects below, but at this moment I aim to highlight the existence of elements inflected in dative, but with a clear subject behaviour for situations that lack volition, control or agency.

In any case, as I have previously noted, the systematicity in the morphological configuration of ergativity is divergent depending on the language, as Figures 3, 4 and 5 reflect (note the roughly coincident diffusion of the ergative patterns with the diffusion of the evidential paradigms of Figure 2).

Figures 3, 4 and 5 reveal the patterns of morphological alignment regarding three parameters: pronominal inflection, marking of noun phrases and verbal inflection. Although the three factors do not always coincide in the same language, as a general rule, the one that does not exhibit a nominativeaccusative pattern is coherent in the three linguistic contexts. Even though, the illustrations on ergativity draw an extension similar to that of evidentiality, they present several problems, such as the lack of dialectal particularities that may contradict the norms of the standard. In any case, (split) ergativity spreads throughout Basque, most indigenous varieties of North America and the Amazonia, the Tibetan languages, Southeast Asia, indigenous varieties of Australia or some Turkic languages.

I will not further extend on the idiosyncrasy of ergativity, since the objective was to give a succinct overview of what is understood as such, but I would also like to underline the importance of diachrony, as happens in the development of evidentiality: the (lack of) existence of ergative patterns is usually the consequence of gradual processes over time that have been crucial for the promotion of evidentiality.

4. Evidentiality and ergativity

My thesis is based on the fact that evidentiality and ergativity are closely related and that the existence of the former is the consequence of the latter (but not vice versa). In order to determine this connection, I then proceed to treat the simultaneity of both phenomena at a typological level, to later deal with Spanish and Italian in particular and, finally, with the other Romance varieties. Likewise, I will pay special attention to the importance of diachrony in the evolution of the two traits and I will argue that the apparent counterexamples are, in reality, a photograph of the development of such diachrony or the result of linguistic contact.

The link between ergativity and evidentiality is based on the fact that both characteristics promote the features of volition, control, agency, and animacy, as opposed to their antonyms. This behaviour is clear for ergativity, either pure or split, but it emerges much more subtly for evidentiality. If the evidential systems at a universal level are considered, we find three different options: languages with evidentiality and ergative-absolutive alignments; not ergative languages with evidentiality that exhibit ergative patterns that are prior to the creation of the evidential paradigm. Finally, there is a third group of languages with evidentiality, but without any ergative model, that have adopted this phenomenon because of linguistic contact. In any of these possibilities, the evolution of the evidential system itself tends to favour the features of (lack of) volition, control, human or agentive, so its configuration is not the result of an arbitrary process either. Below I discuss the three options.

4.1. Languages with both morphological ergativity and evidentiality

The Figures reproduced above suggest that the coincidence of ergativity and evidentiality is not arbitrary. I will not repeat here everything I have outlined earlier, but I do want to focus on the configuration and development of evidentiality as a result of ergativity. The typology found by Aikhenvald (2004) suggests that evidentiality follows a series of hierarchies and implicative stages. For example, if a language has a binary system, it expresses the dichotomy first-hand versus nonfirst-hand evidence or direct versus indirect evidence. Those varieties that only mark a single type of source of information do so for non-first-hand or non-direct. Alternatively, these languages can also mark reportativity versus a zero marker for the rest. However, if a given language develops three evidential distinctions, these commonly follow the parameters of direct, inferred, and reportative, or visual versus inferred and non-visual, or even visual versus inferred and reportative. In any of these cases, there is special inclination to promote the evidence that has been obtained in a more controllable or volitional way compared to other mechanisms for obtaining such information. In addition, in these systems, it is even very likely for sources of information stemming from a third hand (reportative or quotative) to be distinguished, emphasising the lack of control in the obtaining of the source of information.

The same applies to systems with four or more distinctions, since in all of them there is a tendency to discriminate the direct source from the indirect one, or the visual source from the uncontrollable one, such as inference. In other words, there seems to be a special interest in clearly establishing whether what the speaker expresses has been obtained in a controllable, volitional and, to a certain extent, agentive way. Moreover, the greater or lesser clarity in eventual subdivisions also follow this principle: languages begin to discern between degrees of volition (the visual is not the same as the auditory or the olfactory) or degrees of control (inference is not the same as what another person says).

As all authors point out, every language has evidentiality strategies; so, every language is capable of clarifying where the information comes from if the speaker considers appropriate to make it explicit. Likewise, every language displays ergative strategies, in the sense that it can clarify the level of control, volition or agency of a given action. However, to my view, the grammaticalization of these strategies and their possible obligatoriness in the discourse is a qualitative leap, because it means an increasing importance to establish by default the semantic values that are behind their expression. In the case of ergativity, to mark the volition, control and agency of any action; in the case of evidentiality, to mark the degree of volition, control and agency in the way of obtaining information. The evidential distribution suggests this behaviour both in purely and partially ergative languages, but those which are not ergative, but exhibit ergative patterns, also develop the same behaviour: this is the case of German or Peninsular Spanish. And this is again the case in languages without ergativity and ergative models, but which have evidentiality as a result of linguistic contact: IberoRomance (except Spanish) or the Balkan Sprachbund.

In the type of languages that belong to the first class (languages that are morphologically ergative or have a split alignment), the volitional, control or agentive factor is so relevant that it is even possible to find egophoric specialisations in their evidentiality system. Egophoricity refers to the source of information attached to the speaker, versus the source of information that comes outside the speaker. For instance, in Takuu, the egophoric marker arises for volitional acts, while uncontrollable and spontaneous events are marked by a different morpheme (Sun, 2018). Egophoricity occurs widely in Tibetan and Burmese languages, also in the Dagestan area, certain Mongolic languages, and in areas of Papua New Guinea (Aikhenvald, 2018a), that is, in ergative varieties. In Tatar, the evidential specialisation is not only established between direct and indirect evidence, but whether it has been obtained willingly or not (Forker, 2018). The directionality that I defend in this article, by admitting that ergative patterns or alignments promote the creation of evidentiality, is also underpinned in the works that have been done on the languages spoken in the Caucasus. Friedman (2018), for example, dates the implementation of the evidential paradigm in the south of such a mountain range back to the medieval period. His review on other Turkic, Uralic or Indo-Aryan families corroborates this, since the origin of the creation of the evidential paradigm happens later than their development of ergative alignment.

The importance of the factors of volition, control and agency emerges even in the acquisition of evidentials. Fitneva (2018) states that Turkish speakers start to use direct evidentials first at eighteen months, and indirect ones at twenty-one. Within the latter, they first learn those related to inference and, ultimately, the reportative ones. The same happens in Bulgarian, where the new speakers first adopt the evidentials that mark inference and later the reportative ones. The same path repeats in Korean and Japanese, where the reportative is the last to be learned.

4.2. Languages with ergative patterns and morphological evidentiality

In the second place, there are languages or varieties that do not belong to the ergative-absolutive alignment, but they present evidentiality because they have developed ergative patterns: this is the case of German, certain Baltic languages or, in an incipient way, modern Greek, among others. German presents a morphological strategy that marks source of information through indirect speech. Despite the fact that German is considered a nominative-accusative language and even maintains casual pronominal and nominal inflection consistent with such a classification, it presents some models that approach ergative patterns, one of which is the so-called dative subject.

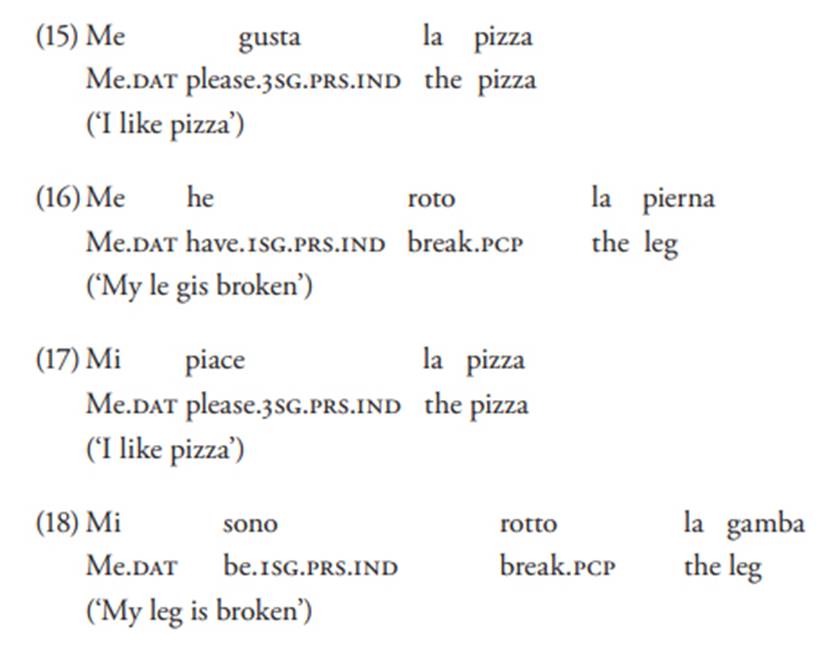

The dative as a case marker usually conveys thematic roles related to the human feature (Givón, 2001). Thus, it arises to materialise the experiencer, the receiver, the possessor, the beneficiary and even the author of an event. Consequently, the dative is usually promoted at the beginning of the speech as the human trait is quite a topical entity. Observe the following examples from Spanish and Italian (15-18).

Sentences (15-18) provide the unmarked order of verbs with an experiencer dative and nominative theme or with a possessor dative and nominative theme. The element that embodies the human traits is expressed first, despite not being the syntactic subject, without further morphological repercussions in these languages, but there are Germanic languages that do undergo another type of readjustment in their casual paradigm.

The concept of dative or non-canonical subject refers to a semantically human element that, morphologically, is marked as dative, so syntactically it is not the subject, but within the word order it does function as such. Germanic languages are a good example of this behaviour. Eythórsson and Barđdal (2005) argue that this linguistic family has always exhibited oblique subjects (particularly datives), although not all of them currently resort to this possibility with the same frequency.

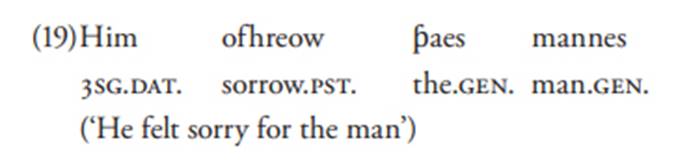

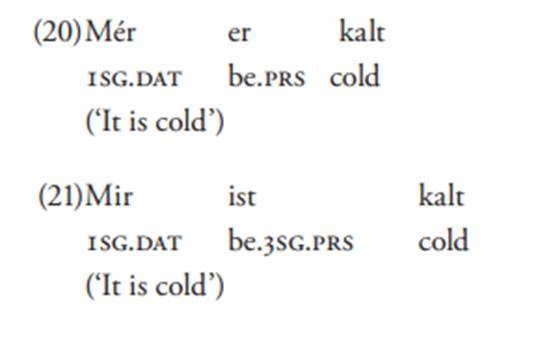

Example (19) (extracted from Eythórsson and Barđdal 2005), from medieval English, certifies that there was no nominative element with which the agreement was established. Instead, there was an experiencer dative and an argument that could be genitive or even introduced by a preposition, thus constituting a prepositional phrase. The non-existence of a nominative subject is still attested in Danish and German (20-21, taken from Eythórsson and Barđdal, 2005).

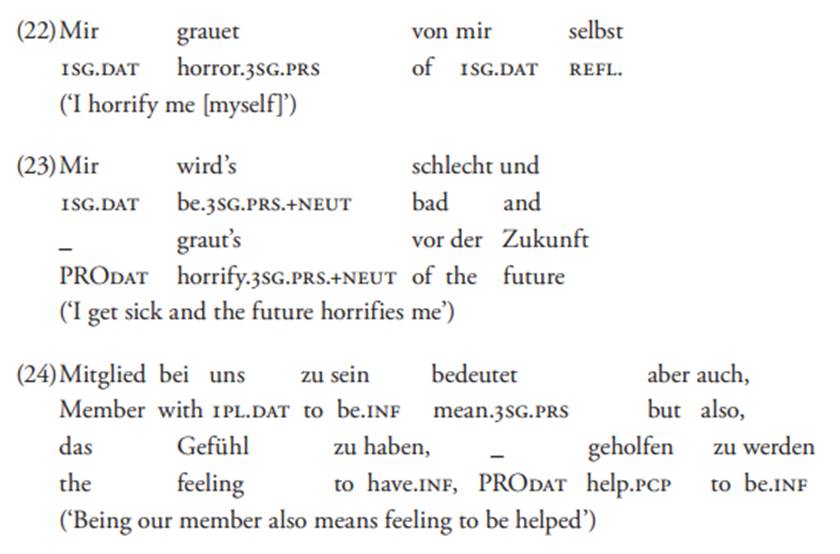

While the expletive subject is optional, the non-expletive form is the most common. The position of the dative at first without a nominative marker in the rest of the sentence is catalogued as a proof of the subject-like character of the dative, but, for Cole et al. (1980), the Germanic languages, especially German, present more evidence of dative subject and promotion of the human trait regardless of the syntactic function (22-24).

Examples (22-24) (reproduced from Cole et al., 1980) show that the obliques exhibit characteristics that pass the test to be subjects (Cole et al., 1980). First, (22) indicates the possibility of having a reflexive co-referent with a dative. In sentences (23-24), there is the ability to omit the oblique referent (dative, in this case) not only in a subordinate infinitive, but in a coordinate. And, although (23) has the expletive es as a syntactic subject, the elision to which I refer is an irrefutable proof of the subject-like character that the dative possesses in these examples. According to Cole et al. (1980), this possibility has always arisen in Germanic languages, regardless of whether either of them has gradually eliminated this possibility or has maintained it. Moreover, the behaviour of

German is observed in medieval English and in the Scandinavian languages in their ancient stage (currently, these exhibit mass neuter, as do the Romance areas with evidentiality, as I will discuss later, Baunmüller, 2000). English and the Scandinavian languages, however, have been turning the experiencer into nominative case, but German has maintained it dative, while Icelandic seems to be in an intermediate phase, although with a high production of oblique subjects. So, it is not casual for German to present evidentiality, in its case via indirect speech.

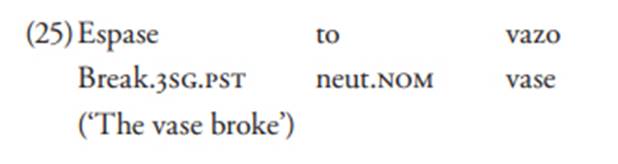

The same directionality applies for Greek. For instance, Verhoeven (2008) states that verbs with an experiencer object tend to be topicalised and precede the verb when the stimulus is non-agentive. In other words, the semantic characteristics of the syntactic subject are crucial for the location of the experiencer object, for it is placed in a prototypical position held by the subject, as long as the entity in nominative is not volitional or agentive. The same can be argued for the order of valencies with regards to an unaccusative verb, where the syntactic subject is positioned in a prototypical location of the object (see 25, de Karantzola and Lavidas, 2014).

Karantzola and Lavidas (2014) put that Greek is characterised by an unusual phenomenon that is mainly attested in ergative languages and, extraordinarily, in English: lability. This causative strategy consists of the usage of the same lexeme to express both cause and effect, without any marker of any kind that modifies the verb. This causative option has evolved in Greek with some unaccusative verbs or verbs with low prototypical transitivity. The sum of all these ergative patterns has resulted in Greek also developing evidentiality by means of its future morpheme (θα). According to Giannakidou and Mari (2012), the evidential reading outnumbers the temporal one in current Greek, and, as a consequence, its primary meaning is inference.

However, the Indo-European languages are not the only ones to show this correlation. In Chukchi, in the Kamchatka Peninsula, a given human subject can be marked either ergative or absolutive depending on the control on the part of this constituent over the action (Polinskaja and Nedjalkov, 1987). In Sinhala, Dixon (1994) argues that the same syntactic subject can be inflected in the nominative or dative, depending on its agency, volition or control. So do other languages with ergative or split ergativity patterns, such as Guarani, Quichua or varieties from the southern Pacific zone (Dixon,1994), since all of them have frequent strategies to discern between an agentive, volitional and active subject with control versus the one that lacks these nuances. In short, its syntactic and morphological behaviour responds to the semantic characteristics of the subject, always based on the traits of agency, animacy, control or volition. In all the mentioned languages, there exists a morphological paradigm of evidentiality and the correlation is so frequent that Chirikba (2003) admits that in Abkhaz, the future has specialised as a resource for conjectures. The same occurs in Korean, where the existence of labile patterns in the causatives (Kim, 2012) has allowed for the development of an evidentiality system (Aikhenvald, 2018a).

This simultaneity of ergative patterns and evidentiality appears again in a number of Portuguese varieties from Brazil and Africa. In the first case, Carvalho (2016) explores the fall of reflexives in certain dialects of Brazilian Portuguese, causing the birth of lability also in that area. And it is precisely in that Amazon area where there is evidentiality, both in its native languages and in the neighbouring Lusophone varieties (Aikhenvald and Dixon 1998). The case of African Portuguese reveals the same dynamics: both in its creoles and also influenced by Bantu languages, the Cape Verdean, Angolan and Mozambican varieties also present lability and ergative patterns and, in many of them, evidentiality (Duarte de Oliveira and De Araujo, 2019).

The thesis that defends that ergative patterns favour the creation of evidentiality and not the other way around is supported by English and, as I will show below, by French. The English language not only presents a high proportion of lability, but some of its varieties modify objects based on semantics. As for the first characteristic, it is from the end of the Middle Ages onwards when English began to increase the list of labile verbs (McMillion, 2006). After this author, English speakers strongly rejected the usage of reflexives, because they associated them to the Scandinavian migration of the time. The inclination to eliminate the reflexive pronouns in any verb caused their gradual transitivisation. As for the objects, English has evolved in marking ditransitive sentences as exemplified in (26-27). In (19), it exhibited the possibility of having sentences without a nominative subject at the same time that lability increased, but currently, this language has tended to what Dunn et al. (2017) call nominative sickness (as opposed to dative sickness in German). Nonetheless, there are still some models that prioritise the human trait over the syntactic status of the constituent (see 26-27).

(26) I gave the book to John

(27) I gave John the book

The possibility of (27), also felicitous in southern Italian dialects, responds to the high topicality that a human entity receives in discourse, regardless of the syntactic function it performs. The specific treatment that human referents are given even in the object environment again reflects a behaviour based on the semantic characteristics of the arguments, rather than on their syntactic status, since the preposition is impossible with non-human referents (see 28-29).

(28) He sent the book to the store

(29) *He sent the store the book

Likewise, the standard variety chooses to distinguish the grammatical gender based on the biological characteristics of the referents, again contrasting animate versus inanimate. In the case of animals, if the sex is known in advance, the gender of the pronoun follows this feature, but if not, the neuter emerges. Even in the normative register, the very choice of object pronouns obeys patterns of animacy or human trait rather than the syntactic case or the semantic role that they can play. In addition, according to Wagner (2004), dialect English has mass neuter and it can also display the exchange of thematic roles for sentences with a non-agentive subject (30).

(30) There came three men

The placement of the subject in a prototypical location held by the object triggers the emergence of the deictic there and, although this example refers to a past event, the present adopts a syntactic agreement, although the subject is postponed. The ergative characteristics of English are now fewer than those that occurred in previous stages, since Dixon (1994) predicts a trend towards the universalisation of nominative-accusative models in the entire grammatical behaviour of a given language, but, although its modal verbs can be employed with evidential value, it is not possible to conclude that their primary, hegemonic or univocal meaning is source of information. English is, therefore, a good example that, despite having clearly ergative behaviours, it has not developed a morphological paradigm of evidentiality. Moreover, it exhibits the same components as the Baltic languages, Modern Greek, and even dialectal Peninsular Spanish, as I will show later. However, the elements that favour the creation of evidentiality (all of them of ergative nature) remain without having still prompted it, whilst the emergence of the abovementioned evidential paradigms have been motivated by the same elements that exist in English.

4.3. Evidentiality by linguistic contact

Lastly, there are languages that have developed a system of evidentiality, but which, in turn, do not exhibit any ergative behaviour. The reason for this contradiction lies in the fact that such a paradigm is a direct influence from a neighbouring language. This reality is widely documented. Without going any further, Aikhenvald (2018b) demonstrates the presence of this phenomenon in Turkish JudeoSpanish, precisely as a direct influence from Turkish; the same applies to the Balkan Sprachbund or Armenian. But even under this possibility, the language that develops evidentiality by contact can adopt the morpheme of the one that has established the influence. Soper (1996) argues that Tajik (from the Iranian family) has adopted the suffix -mis from Uzbek (from the Turkic branch) for nonfirst-hand sources. The same happened in Kyrz by contact with Azeri, always designating inference or reportativity, that is, indirect evidence. Turkish itself maintains a morphological distinction between direct versus indirect evidence, either if the latter comes from a third source or from the speaker’s own inferential processes (Ünal, 2018).

Aikhenvald (2004) holds that Turkish is precisely the greatest irradiator of evidentiality in its surrounding area. This author argues the same for the Baltic Sprachbund, since Latvian and Lithuanian accept evidentiality as a morphological paradigm by influence from Estonian. This behaviour is attested in the Balkan Sprachbund too (Aikhenvald, 2004) and throughout the Caucasus. This influence has jumped beyond this Eurasian mountain chain, for lability has also appeared in Russian (Letuchiy, 2015), despite its inclination to emerge in ergative languages or with some type of split pattern (Haspelmath 1993; Letuchiy 2004; Letuchiy 2009; Creissels 2014).

The strong interrelation of the linguistic families that share a border in Central Asia is quite relevant. Although the literature claims that Turkish is the greatest disseminator of evidentiality around, this does not mean that, previously, it has not adopted this possibility due to linguistic contact with the Caucasus. This is what Chirikba (2003) suggests in her research on Caucasus. Evidentiality there appears in its most primitive linguistic stages and its varieties started to develop close contact with Turkic languages from the end of the Middle Ages onwards. In any case, the reciprocal influence that the Turkic, Caucasian, Altaic, Finno-Uralic and even Indo-Aryan families have had is undeniable, showing the establishment of evidential paradigms from the Balkans to Siberia, passing through all of Asia Minor, the Caucasus and Central Asia. The directionality of this fact remains unsolved, but the interconnection among all of them is so great that Johanson (2003) states that evidentiality is gradually being lost in Turkish dialects that border Indo-European languages that have not had this strong link. This contact also affects Persian, where, according to Perry (2000), its future has come to connote inference primarily.

The Iberian Peninsula is another example of this behaviour, since the evidentiality that is attested in Portuguese, Galician and Catalan seems to be caused by the direct influence of Spanish. The correlation of ergative patterns and evidentiality replicates in other dialects of non-European Spanish. And again, linguistic contact also plays a role in the diffusion of both ergative patterns and the creation of morphological evidentiality. Thus, Spanish in contact with Quichua presents leismo and omission of the unstressed pronoun in contexts in which the standard requires it because the latter language follows animate-non-animate criteria, instead of the syntactic function of the constituents. Quichua also has morphological evidentiality (Flores Chávez and Vega Vicente, 2021), which has even caused the Spanish of that area not only to use the MF or the COND to express source of information, but also to use perfect tenses for that purpose (Pfander and Palacios 2013).

4.4. Romance languages

The theoretical argumentation that I have developed in the previous section can also be demonstrated with the situation of the Romance varieties. The fact that the morphological marking of evidentiality is one more branch of a coherent behaviour to distinguish between the concepts of volition, control, agency or animacy is corroborated by current and historical examples. I have analysed the three possibilities that favour the morphological creation of an evidential paradigm at a universal level, and these same three options can also be extrapolated to the Romance languages. As I noted at the beginning of the article, the greatest controversy affects the Romance languages, surely because of the same lack of consensus in establishing what evidentiality is. However, below, I will show that the ergative patterns attested in western Peninsular Spanish have caused this zone to develop a system of evidentiality and the same applies for the southern varieties of Italian. The rest of Italian dialects and the other Ibero-Romance languages have spread this same paradigm as a consequence of linguistic contact, although each one undergoes a different phase. Finally, I will argue that French is the only language that has not adopted this phenomenon and that it behaves like English, since it presents clear ergative patterns that have not yet triggered an evidential morphological paradigm.

4.5. Peninsular Spanish and Italian

Evidentiality in Spanish has been studied by numerous academics, among which the works of Escandell (2014, 2022) or Squartini (2001) stand out. In all of them, the data they handle comes from introspection or from ad hoc questionnaires. All of them affirm that evidentiality is embodied in the use of the MF for inference or conjecture and the COND for reportativity. In fact, Escandell (2019) argues that, at least in the case of the MF, temporal values are restricted to cultivated speech, since in the relaxed, colloquial, non-cultivated sphere the inferential reading is the first semantic value that every native learns before their schooling.

Aaron (2014) investigates the semantic evolution of the Spanish MF and comes to the conclusion that both temporal and evidential meanings have coexisted since the appearance of the MF, but the conjectural value has historically been scarce and restricted to cultivated speech. Even at the beginning of the 20th century, this author finds more samples of conjectural MF in cultivated contexts than in the opposite situations. However, in all cases, the inferential MF is minor. It is as the 20th century advances that the conjectural MF increases in non-cultivated speech, but never outnumbers the temporal value.

The nuance about the textual typology on which most of the analyses applied to Spanish are based is relevant, since it restricts the function of evidentiality to the standard variety. In addition to the fact that the mentioned works are based on the standard or on the cultivated spectrum, none of them statistically establishes the unmarked value of all the possible readings of both tenses. This makes authors put forth that virtually all Romance languages have evidentiality by means of the MF and the COND, since in all of them there is an evidential reading in coexistence with temporal or modal. Nevertheless, if dialect data are taken into account, the conclusions change.

The first tokens referring to non-cultivated and dialectal tokens are found in the atlases carried out in the first half of the last century in over 1,500 localities. These early works were based on the repetition of pre-established words and sentences by elderly informants from a rural environment and with a low educational background (NORM). The methodology is by definition controversial, because in principle it does not guarantee the spontaneity of the speaker, but the profile of the informants ensures the linguistic production without the conditioning of the standard. These atlases were: Atlas linguistique de France (ALF), which covers France (except Brittany), the French-speaking area of Belgium and its counterpart in Switzerland; Atlante linguistico ed etnográfico dell’Italia e della Svizzera meridionale (AIS), which covers Italy, the Italian zone of Switzerland and Istria; Atlasul lingvistic român (ALR), which covers Romania and Moldova; and the Linguistic Atlas of the Iberian Peninsula (ALPI), which covers the entire Peninsula plus the Balearic Islands. Hence, we have a geographical and linguistic representation of the European Romance languages of a century ago with regard to numerous phenomena of all kinds and not just lexical or phonetic. The design of the questionnaires preestablished a large number of words and sentences that aimed to record a specific grammatical, lexical or phonetic particularity; moreover, the repertoire foresaw the appearance of the same phenomenon in various sentences precisely to contrast its frequency or possible gradual behaviour depending on the syntactic, semantic, phonetic context, etc. Regarding the MF and the COND, their results have been mapped by Lara (2021b, 2021c), as I will reproduce below, but it is necessary to make two observations: firstly, there are no data on Romanian, since this language did not develop an MF and COND comparable to the rest of Romance varieties; secondly, there were no sentences that contained an MF or a COND with an evidential nuance (except for one in ALPI).

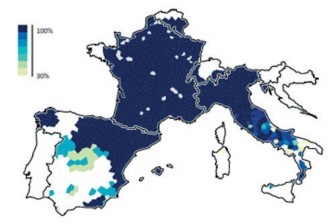

In Figures 6 and 7, I draw the non-evidential usage of the MF and the COND in Europe one century ago, taken from Lara (2021b).

Figures 6 and 7 account for the extension of both tenses as non-evidential resources a hundred years ago. Although Romanian is excluded from this study, the study by Lara (2021b) shows that both tenses were, above all, non-evidential in oral and non-cultivated contexts in almost the entire Romance spectrum, except in very limited areas. In the first place, the MF was scarce or nonexistent in the southern half of Italy, as well as its islands; likewise, this tense was not frequent in western Peninsular Spanish for these values, although it did appear in greater proportion. The COND occupied a larger space in the Italian peninsula, except in the south and the islands, while it was non-existent in Portuguese and much of Spanish.

The photograph shown by the data from a hundred years ago gives clues about the birth of evidentiality in the different Romance varieties, but first it is necessary to comment on a peculiarity that comes from the two observations that I made before: the single sentence that the ALPI envisaged with an inferential MF agreed in perfect. This detail is essential, because perfect tenses lend themselves more to accepting evidential values rather than the simple ones. Stage (2003) states that the conjectural MF in French is only possible when inflected in perfect, while it is not accepted by the standard variety in its simple form.

The percentages reflected in figures 6 and 7 lead to postulate that, a hundred years ago, the MF was evidential in western Peninsular Spanish (since its non-evidential readings are secondary) and, in principle, throughout southern Italy and, gradually in the rest of the country, for the southern zone does not present a single occurrence of non-evidential MF. Indeed, Ledgeway (2009) states that the MF in the southern half of Italy has been only conjectural since the nineteenth century, when it stopped expressing temporality.

In order to affirm this last idea, it is necessary to compare the evolution of the MF and the COND at the dialect level and not only describe the state of a hundred years ago. However, an in-depth analysis is only possible for Ibero-Romance thanks to the current corpora which, with a methodology that does favour spontaneity, have been carried out since the 1990s. I refer to the Corpus Oral y Sonoro del Español Rural (COSER) to the Spanish; Corpus Dialectal para o Estudo da Sintaxe (CORDIALSIN) for Portuguese; Corpus Oral Informatizado da Lingua Galega (CORILGA) for Galician; and Corpus Oral Dialectal (COD) and Corpus Dialectal del Català (DIALCAT) for Catalan. All of them are based on the semi-conducted interview with the same speaker profile as that of the atlases from the beginning of the 20th century. In this sense, the results guarantee the dialectal evolution of the MF and the COND without standard priming during the last hundred years. It should be added that the total number of municipalities surveyed in these corpora reaches up to 300 localities.

Figure 6 suggests that the MF began to be evidential in western Spanish a century ago, since non-evidential values were minor, although they could arise up to 30% of the times in which such a tense was expressed. In order to comprehend if the cartographic results were the prelude to the specialisation of the MF (and the COND) as an evidentiality paradigm, it is necessary to compare them to the current distribution (Figure 8 and Figure 9).

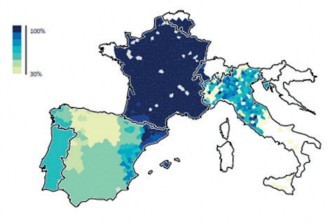

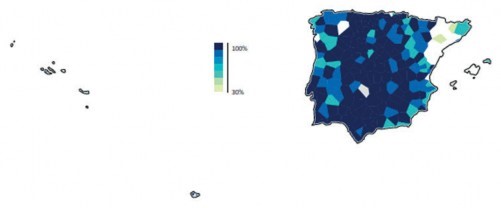

Figure 8 and Figure 9, taken from Lara (2021a), reflect that the evidential usage becomes the unique in most of Peninsular Spanish, especially the west, in line with the data in Figure 6. Again, the MF in its evidential meaning is greater than the COND. Therefore, evidentiality in Ibero-Romance originates in the west of Peninsular Spanish and, later, spreads to the rest of the territory. The conclusions of figures 8 and 9 are summarised in Table 2.

Table 2 Non-marked values of Ibero-Romance MF and COND (Lara, 2021a)

| Portuguese | Galician | Spanish | Catalan | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MF | Evidential | Evidential | Evidential | Temporal (Catalonia and the Balearic Islands) Evidential (Valencia) |

| COND | Evidential | Modal | Evidential | Modal |

Table 2 suggests that the MF is evidential in all Ibero-Romance varieties, including Valencia Catalan, but not from Catalonia or the Balearic Islands, while the COND is only evidential in Spanish and Portuguese, but not in Galician and Catalan. The numbers indicate that the primary, hegemonic and, in many cases, unique value of the MF in Spanish is the inferential one. It is also primarily in Portuguese, Galician and Valencian Catalan. In the case of the COND, the same applies for Spanish and Portuguese. The Figures insist that western Peninsular Spanish is the focus of evidentiality in this language, since it is the area where, a century ago, the MF gave less proportion of temporal value and the area where the MF is currently only evidential. The COND is also stronger as evidential in the same region compared to other territories.

Following the thesis of this article, the arising of a morphological paradigm of evidentiality is the consequence of a series of previous ergative patterns that have motivated its appearance. This assumption implies that, if the evidentiality of Spanish emerged in the west of the peninsula, that geographical area must have a series of ergative features and that they had to be present more than a century ago, since evidentiality starts at that time. The dialectal peculiarities that coincide with this zone underpin this theory.

On the one hand, western Peninsular Spanish possesses lability. The labile verbs recorded in dialectal Peninsular Spanish are entrar (‘to enter’), quedar (‘to stay’) and caer (‘to fall’) (Lara, 2020).

(31) El coche entró en el garaje - Entré el coche en el garaje

(‘The car entered the garage - I entered the car into the garage’)

(32) Los libros se quedaron en la mesa - Me quedé los libros en la mesa (‘The books stayed on the table - I stayed the books on the table’)

(33) El vaso (se) ha caído - He caído el vaso (‘The glass fell - I fell the glass’)

Occurrences (31-33) (extracted from Lara Bermejo 2020) show the transitivisation of the three unaccusative lexemes at the expense of the lexical opposition meter-entrar, dejar-quedar and tirarcaer. The emergence of this phenomenon is restricted to the west of the peninsula, although its geographical incidence has been decreasing over the years, according to the bibliography. While the dialectal monographs of the 1960s and 1970s circumscribed lability to almost all of Castilla y León, Extremadura and part of western Andalusia, as well as areas of western Castilla-La Mancha (Zamora, 1970; Alvar 1996; Montero, 2006; García, 1994; Ariza 2008), the fieldwork carried out by Lara (2020) locates this phenomenon in Extremadura and the westernmost area of Castilla y León, without reaching León, with uneven incidence in western Castilla - La Mancha. However, the greater or lesser proportion of lability is subject to a series of factors of a semantic-syntactic nature that I reproduce in (i-iv).

(i) Entrar > quedar > caer

(ii) Unwilling human subject > non-human subject > willing human subject

(iii) Non-affected object > affected object

(iV) Atelic > telic

The hierarchies of (i-iv) establish that, if a speaker transitivises the verb caer, s/he will necessarily do so with those to the left; likewise, if s/he transitivises any of such verbs with a non-human subject, s/he will do so with an involuntary human subject, and so on. As can be seen, the probability for a verb to be labile is inversely proportional to the degree of transitivity of the subject, object and action.

The causative behaviour that I have just described is not the only trace of ergativity, since I can refer to at least three non-nominative-accusative features that are attested in (part of) the area where lability spreads. The first of them is leísmo, laísmo and loísmo, as well as the development of an own agreement for non-countable entities (mass neuter). Its incidence responds to patterns of animation, agency or volition, diffusing throughout a large part of Castilla y León, Cantabria, Asturias, the Basque Country, Navarra, La Rioja, Madrid and Castilla La Mancha, with attempts in the east of Extremadura (FernándezOrdonez, 1999). Its extension, therefore, coincides with the easternmost region of lability one hundred years ago, as well as with the municipalities of eastern Extremadura, western Castilla-La Mancha and central-western Castilla y León, where lability continues to appear today.

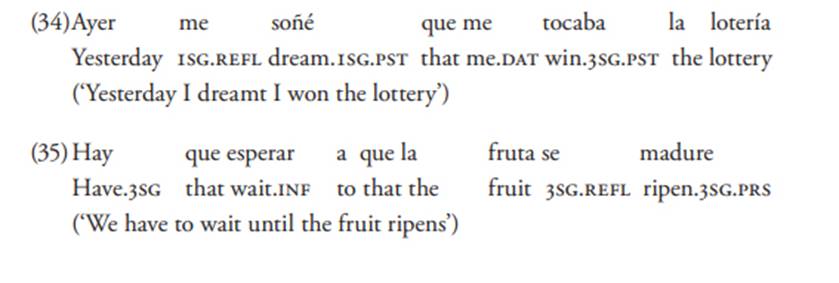

The second of them is the usage of reflexive pronouns in verbs with a non-volitional or nonhuman subject, precisely to mark this lack of agency. Lara (2020) notes the existence of utterances like (34-35).

The instances (34-35) (taken from Lara, 2020) imply a strategy to mark the semantics of the arguments of the verb, since the subject of the verb does not exhibit the same properties in all the sentences; the reflexive emerges precisely in those which lack agency, volition, or control.

The third feature has to do with a type of leísmo, called false leísmo by Fernández-Ordóñez (1999), consisting of the systematic employment of the dative le(s) regardless of the syntactic function of the object and the sex of the referent to mark politeness. Gómez (2021) shows that its use completely escapes the influence of true leísmo, since it responds to the marking of a human referent through the grammatical case that usually expresses it: the dative. It is the same type of strategies that occurs in Germanic languages, as discussed above.

The examples are a sample of the insistence of this geographical area to mark the features that have to do with human, agentive or volitional. They occur dialectally, although there are particularities that have spread further away from that region or have even been established in the standard, but they reflect clear ergative patterns in all their meanings (morphological, syntactic and discursive), prompting the creation of evidentiality, precisely in types of information that lack control or volition on the part of the speaker. In the first place, the MF specialises as inferential: a type of source of information that is beyond the subject’s control, but that continues to originate from the subject and not from a third party. The inferential reading conveyed by the MF refers to present or future events, but in a second stage, the COND becomes evidential too, marking inference referred to a past event. Finally, this tense further develops reportative nuances: again, a source that escapes the volition of the speaker, but highlighting the degree in the lack of control, since the information comes from a third party.

The other Romance varieties, both from the Iberian Peninsula and the rest of Europe, work identically, with one exception: some of these have adopted an evidential paradigm by linguistic contact. The only language that has autonomously developed a morphological system of evidentiality has been Italian, thanks to the evolution of its southern dialects. If Figure 6 and Figure 7 are observed, the beginning of the 1900s indicates that the MF (and, to a lesser extent, the COND) was non-existent as a temporal value. The deduction that, at that time, the MF was already evidential in that region is supported by the bibliography that deals with this phenomenon, as well as by the comparison with Spanish and the same concatenation of elements of an ergative nature that emerge there.

As we lack dialect corpora similar to those of the Ibero-Romance languages, the only evidence we have is the research carried out by Ledgeway (2009) or Rohlfs (1968). They state that the MF is mainly a strategy to express conjectures, although its temporal value remains high in the northern half. Berretta (1994) affirms that, in the acquisition of Italian as L1, learners adopt the use of the MF first in its inferential version to later incorporate the temporal one. This path is not exclusive to the varieties of the south, but can be circumscribed to the entire Italian geography, although it is true that the south has gone further by not resorting to the MF for temporal values and replacing it with other alternatives. As was the case with Spanish, both readings have always coexisted, but at a given moment, a certain region has decided to grammaticalise this tense for source of information.

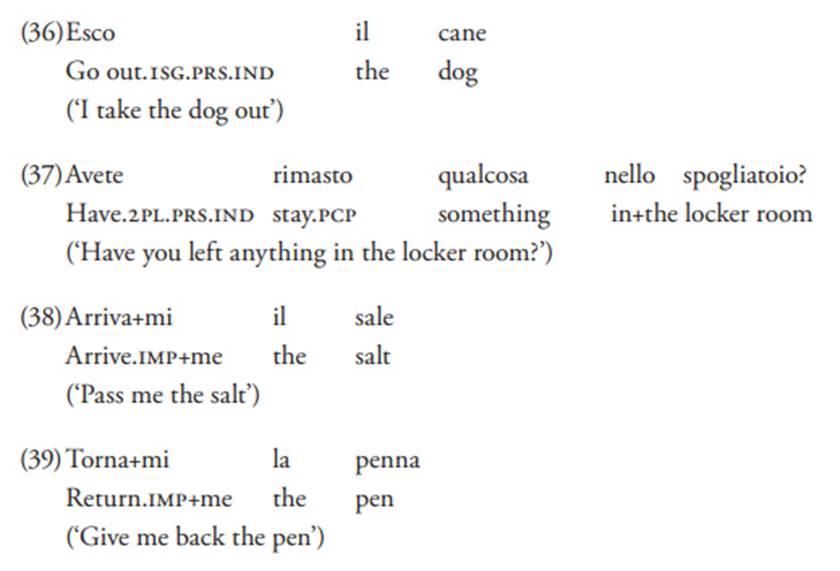

The bibliography suggests that, what was common for the southernmost part of Italy, has been increasing in the rest of the country and that the south has been the focus of this phenomenon. However, as occurs with Spanish, the birthplace of evidentiality in Italian is not casual and responds to the conjunction between ergative patterns and the creation of an evidential system, the latter always being a consequence of the former. Southern Italian presents a distribution similar to that described for western Spanish. According to Cerullo (2021), there is a series of unaccusative verbs that are used transitively at the expense of periphrastic constructions, formed by a verb with low lexical content ( fare, portare...) plus a preposition or adverb (su, giù, fuori…) (36-39, extracted from Cerullo 2021).

The inventory of labile verbs in dialectal southern Italian remains, to this day, unknown and, practically, we only have the references of Cerullo (2021), without there being an in-depth study in this regard yet. In addition, Trumper (1997) argues that transitivisation occurs with the verb entrare (‘to enter’), while Sornicola (1997) points it out for the case of rimanere (‘to remain’). Also, according to this author, this transitivisation of unaccusatives has led to the reorganisation of third-person clitics based on the human trait of the referent. Thus, certain intransitive verbs allow the choice of an accusative clitic if the reference is human at the expense of the canonical indirect object. The semantic factors that affect Italian lability replicate those referred to for Spanish: it arises in contexts of low transitivity, with non-volitional subjects or unaffected objects.

Likewise, apart from presenting lability in the extreme south, the southern region possesses other strategies that focus on the human, agentive, volitional or control factor. They have differential object marker, like standard Spanish. According to Ledgeway et al. (2019), the different dialects of the south mark the human entities that function as a direct object through the preposition a, unlike other inanimate or non-human referents. Moreover (1997) says that the southern zone of the Italian peninsula can universalise the accusative clitics for any syntactic context if they refer to a human entity, but, although the usage of the accusative contravenes the tendency of expressing the human trait by means of the dative, the reason underlies the transitivisation of intransitive verbs. And, as in dialectal Spanish, the same southern area has developed mass neuter in different syntactic contexts (Maiden, 1997). Finally, Loporcaro (1997) emphasises the existence in the south of indirect human objects turned into direct objects even in ditransitive sentences, as in English, with the human referent placed before the patient.

4.6. Ibero-Romance and French

While western Spanish and southern Italian have created an evidential morphological system through the MF and/or the COND precisely because of the dialectal ergative factors that favoured this development, the rest of Peninsular Spanish and central-northern Italian varieties have incorporated it as an influence from their respective epicentres. They have not been the only ones, since the other Ibero-Romance languages have followed the same process. The comparison of figures 6 to 9 is clear in this regard: a hundred years ago, neither Portuguese, Galician nor Catalan presented low percentages of temporal MF, so its primary meaning was time. Current data reflects a dramatic change in the west of the Iberian Peninsula and a process of change in Catalan, in different phases depending on the Catalan-speaking variety. Thus, the Valencian area has ended up developing evidentiality in the MF (but not in the COND), since inference is the primary one, but the Catalonian and Balearic areas have not yet reached that stage, although they dialectally admit this possibility; as a matter of fact, Catalonia accepts it to a greater degree now than it did a hundred years ago.

It should be noted that none of these linguistic areas presents a sequence of ergative patterns like the one described for western Peninsular Spanish, so the only possibility that they have imitated the Spanish model is through contact. Although Bazenga and Rodrigues (2019) and Segura da Cruz (1991) point out an incipient lheísmo in certain southern areas of Portugal, in the style of person leísmo in Spanish, there are neither lability nor pronominal confusion based on the semantics of the actants. The maximum exponent of syntactic configuration based on the parameters of agency and volition is the non-marked order of constituents with unaccusative verbs, since the postverbal subject position is also frequent; also, there emerges an incipient lheísmo of courtesy to differentiate the human from the non-human referent (Bazenga et al., 2016).

The geolinguistics of Figure 8 and Figure 9 supports the thesis on linguistic contact, since not only has evidentiality penetrated earlier in the varieties further west, on the limit with its focus, but, for Catalan, it has been Valencia the one that has adapted to this particularity, repeating the secular behaviour that it has had with respect to other linguistic phenomena that appear in Catalan. According to Fernández-Ordóñez (2011), the Iberian Peninsula has been recurrently exchanging phenomena, regardless of the language spoken, and these exchanges have been lexical, phonetic and morphosyntactic, coming from east to west or from north to south and vice versa. The entry of the MF and the COND is also an influence of the east of the peninsula, to such an extent that, according to Cunha and Cintra (1992), it was never popular in Portuguese, where it was limited to cultivated language.

The case of Catalan is essential to corroborate what I put forth: its area adjacent to French also lacks evidence. I have already argued and commented that French is not yet evidential and this fact is relevant, because the Gallo-Romance features in Catalan are well known and the evidentiality of Catalan occurs the further south of its area we are, being Spanish the clear influence of this particularity, as it has been for the allomorph -ra instead of -se for the imperfect subjunctive (Lara, 2019). The fact that Catalan has been incorporating the MF and the COND very late for evidential readings is emphasised by the same statements in the literature in this regard, since Badia i Margarit (1962), Wheeler et al. (1999) and Solà and Rigau (2002) insist that in Catalan the inference is conveyed by means of the modal deure (‘must’), although all of them very briefly recognise that, colloquially, the MF may appear for conjectures.

The reality of French is an additional proof to the whole argument: it lacks evidentiality, even despite presenting attempts at lability. Lability in French is a relatively recurrent topic in the academic literature, but not all authors use the term in the same way. Larjavaara (2000) opts for a very broad definition, since she admits certain reflexives in the same category, but she notes the labile behaviour of verbs such as sortir (‘to go out’), monter (‘to go up’), descender (‘to go down’) and apprendre (‘to learn’) though this labile usage is standard. Acceptability on the part of the normative variety is not per se a criterion for my argumentation, although I have to acknowledge that its acceptance also on this level is a qualitative leap in the prestige of lability, but current French also has labile uses of verbs that the standard completely rejects, especially tomber (‘to fall’).

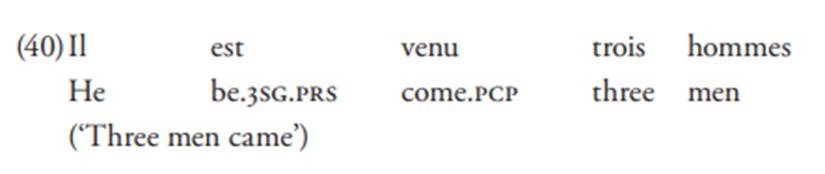

Lability is not the only element that is based on the semantic features of the subject in this language, but Bilous (2011) underlines the plausibility of postponed non-volitional subjects precisely to mark such lack of agency, control or volition (40), turning any verb into transitive.

Example (40) (from Bilous 2011) shows the possibility of sending to a typical object position the arguments that, in an unmarked position, are the subject, as in English. The reorganisation of the argument provokes the transitivisation of the unaccusative venir, causing French to resort to the expletive for having to produce a subject. Furthermore, the distinction of the auxiliary in the configuration of the perfect tenses, depending on the unaccusativeness of the verb: être (‘to be’) for unaccusatives and avoir (‘to have’) for unergatives and transitives also play a role.

The problem, to my view, with the analyses on French with regard to evidentiality is that they are based above all on cultivated speech. Not only that, but certain authors determine that French has evidentiality by the mere fact that its MF and COND can connote inference and reportativity, without there being a reflection about the frequency of that semantic nuance in confrontation with the temporal or modal value. Spanish was always characterised by an MF that could serve for time and inference, but this last possibility appeared in the cultivated sphere (as the figures and the bibliography confirm) and represented a minimum percentage compared to the temporal value of this tense. It is likely for the MF and the COND to later become really evidential by exhibiting this semantic reading hegemonically, especially taking into account the ergative features that exist in French, but it cannot be said that this is the case today.

The importance of the discursive genre is essential, since Spanish itself proves that, although the COND is valid as an inferential value referring to a past event both colloquially and in cultivated contexts, its reportative meaning is limited to the journalistic register and, therefore, to a cultivated spectrum. The probability for the COND to behave as reportative has increased over time, but even today, this possibility is conditioned by genre (Romero Gualda 1994). Back to French, Van de Weerd (2018) shows examples of reportative COND in eighteenth-century legal documents and Vatrican (2010) establishes the use of evidential COND in journalistic contexts. Moreover, despite the fact that part of the bibliography has accepted its status as a language with evidentiality for allowing MF for conjectures in very specific circumstances, the authors who have carried out research on oral language in this regard agree in determining that the conjectural value is minimal, it does not usually occur in non-literary language and is therefore constrained to a very specific register. So, the MF in French is currently a tense to express time (Poplack and Turpin 1999; Lyons, 1968; Tomaszkiewicz, 1988). Even (2007) goes so far as to affirm that the examples with conjectural MF that appear in studies by Palmer (1986) or Fleischman (1982) are made up and do not reflect the real usage.

The situation of French (and historically of Spanish) in this respect is corroborated by the evolution of other Romance varieties: Rohlfs (1968) also restricts the use of the reportative COND in Italian to journalism; and, finally, Oliveira (1985) also refers to the Portuguese evidential COND as a typical strategy of journalistic texts to mark reportativity. Again, regarding the reportative COND in French, Aikhenvald (2004), following the data of Dendale (1993), confirms that this resource is merely journalistic or arises in cultivated texts, without anyone providing a single data of oral or non-cultivated reportative COND. The investigation by Martines (2017) demonstrates the early use of the MF as a conjecture in Catalan, but limited to the 13th century. The sample replicates the case of French and other languages, where the coexistence of temporal and evidential reading has always existed, with a clear preponderance of the former over the latter and with the latter limited to cultivated speech. Therefore, it is in the south of Italy and in almost the entire Iberian Peninsula, where the evidential value has jumped to the colloquial or non-cultivated level, and now the temporal meaning is mainly a cultivated resource to express future time. Consequently, the existence of evidentiality in Portuguese, Galician and part of Catalan responds to the fact that dialectal Spanish has spread it to the rest of the Iberian Peninsula, while standard Italian and the northern varieties have incorporated morphological evidentiality by influence of the southern dialects.

However, both in Spanish and in the other Romance languages, the directionality in the creation of evidentiality or in the increasingly frequent use of certain evidential strategies follows the same path. The first tense to become evidential is the MF and then the COND; the first source of information to be conveyed is inference, followed by reportativity. Not only has this happened in Spanish and Italian, but Portuguese offers one more proof: both its MF and its COND are useful for inference and reportativity. While the reportative version of both tenses is a matter of register and cultivated discourse, the inferential choice is primary in oral and non-cultivated language, with the same complementarity as in Spanish. Once again, the specialisation is based on a marker that expresses lack of control, but which comes from oneself (inference), to later create another that lacks volition, but has even less control on the part of the speaker (reportativity).

5. Conclusions

The system of evidentiality in Spanish, embodied in the MF and the COND, to connote inference and reportativity, arises in western Spain as a consequence of the ergative features that have previously developed in this area. With time, this phenomenon has spread to the rest of the Spanish-speaking region, as well as the Catalan-speaking area of Valencia, European Portuguese and Galician. Its birth and evolution coincide with the development of evidentiality in Italian, whose MF specialised as inferential more than a century ago in the south of the country, precisely thanks to the concatenation of ergative traits that also existed there.

The rest of the Romance varieties lack an evidential inflectional system, despite having the same strategies to express inference and reportativity, but the frequency of the evidential nuance is secondary and has always been restricted to cultivated register. This fact is especially relevant for French and, although this language has ergative patterns that favour the birth of evidentiality, the frequency of evidential values is minor in comparison to temporal ones. However, although the tendency to ergativity seems to be a sine qua non condition for the development of evidentiality (see German, Amerindian or Caucasian languages), the existence of this characteristic can occur as a consequence of linguistic contact. This is precisely what has happened in the Ibero-Romances (except Spanish), the languages that surround Turkish, the Hispanic varieties of the Andes or in the Sprachbünde of the Balkans and the Baltic.

The reason that explains the correlation between ergativity and evidentiality lies in the fact that both phenomena affect the semantic features that have to do with the degree of volition, agency and control on the part of the subject. That is why conjecture (indirect evidence) and reportativity (indirect evidence and from a third source) are the first to settle in the birth and development of evidentiality, compared to another type of direct source, which remains unmarked. This happens not only in the Romance languages, but in a general way cross-linguistically, allowing for the understanding the reasons why there exists evidentiality in a given language at a given moment and why it evolves the way it does.