1. Introduction

English language teaching involves students’ cognitive diversity that teachers must face every day in the classrooms. In fact, it is strongly evident that in rural schools, diversity can be found to a greater extent as there are not as many schools in a town (Bonilla-Mejía & Londoño-Ortega, 2021); these limited schools have to welcome all the population from the town and its surroundings. In other words, students may have a geographical connection, but they have completely different backgrounds that come together to an institution to be provided a quality education. For this reason, there is a need to recognize how teachers implement differentiation strategies in their classes, especially through the creation, adaptation, and use of pedagogical materials. In such a manner, the main objectives of this study are to explore the views that the participant teachers hold about differentiation strategies, their conceptions of materials development, and how they unite these in order to convey differentiated instruction inside diverse classrooms.

In Colombia, there is not enough research on the implementation of differentiation strategies in rural contexts, so it became relevant to study this as it is a way to start building inclusive classrooms. According to Ramos & Aguirre (2014), teachers are “active agents of change” (p. 137). In that way, it can develop an inclusive environment and enhance the efficacy of teaching and learning.

For these reasons, through some observations and interviews, we have been able to discern how they include differentiation strategies in their classrooms through materials, in order to advocate for their students’ different cognitive profiles.

2. Theoretical framework

2.1. EFL Teaching in Colombia

English as a foreign language or EFL is widely known as the study of English by different people in countries where English is not the primary language. However, over time, English has become an essential requirement worldwide. This is true for countries such as Colombia, where using English is associated with higher education or even more business opportunities. To illustrate, students in college must achieve a certain level of English before graduation; also, major companies are demanding employees be proficient in English in order to be hired. Therefore, there is a concern about the professional development of Educators who teach English in Colombia, since the teachers’ training is insufficient at times to perform effectively in a real context where the L2 is needed to demonstrate and teach knowledge to English learners, such as teaching practices at rural schools. According to Farrell (2006), “the ideals that the beginning teacher formed during teacher training are replaced by the reality of school life, where much of their energy is often transferred to learning how to survive in a new school culture” (p. 212). For this reason, EFL teachers are in continuous professional growth and preparation in order to reduce the impact of the challenges they face in real-world situations.

2.1.1. Teacher training in Colombia

Teacher training in Colombia has undergone a series of changes in the last decade. As Bustamante (2006) said:

Teacher training then cannot be a mere revision of didactic formulas or training in specific disciplines, it has to be the space that welcomes the teacher’s concern to transcend, the place where, through reflection, they can clarify their position regarding educational problems, their role in social dynamics, their way of understanding the world. (p. 7)

This means that teachers’ training goes beyond the development and professional projection of the educator. Thus, teachers have the opportunity of taking a critical look at the educational system in order to understand their roles as part of it and help to enhance the academic quality.

In such a manner, there are different institutions that focus on the formation of teachers in Colombia such as the superior normal schools, the faculties of education, undergraduate programs, and undergraduate professionalization programs for non-graduates who enter the educational system (MEN, 2013). In light of this, there are 70 faculties of education in the country, 45 are private and only 25 are public. In addition, there are 124 accredited normal schools that are part of the National Educator Training System.

2.1.2. Bilingualism Programs in Colombia

Ministerio de Educación Nacional (MEN) in English Ministry of National Education, with the purpose of improving the quality of education in English in the Colombian territory, formulated and implemented the National Bilingualism Program (NBP) with the objective of training residentes with the ability to communicate in English; which entails providing education at the elementary, intermediate, and advanced levels. The objective of the NBP is to make Colombia a bilingual nation comparable to world standards, which would allow the territory to insert itself in a world of communicative projects, in the universal financial system, and interculturalism (MEN, 2020). To conclude, the program includes strategies including establishing standards for English proficiency, assessing the skills of teachers, students, and graduates of language programs, providing professional development opportunities for teachers to improve their language proficiency, teaching methods, and incorporating modern technology and resources for teaching and learning English (MEN, 2020).

For this reason, learning a foreign language in a Colombian context is considered one of the most important requirements for the future life of the people, since English allows the country a high academic status as it is recognized as a universal language.

2.2. Materials Development

Many scholars have recognized materials development (MD) as a relevant component of English Language teaching, which can help both students’ learning process and teachers’ practice through the creation and experimentation of compelling material. Hence, it fosters a friendly and inclusive environment that allows boosting students’ and teachers’ engagement. In this regard, Tomlinson (2001) considers MD as a field of study because it requires research into “the principles and procedures of the design, implementation, and evaluation of language teaching materials’’ (p. 66). As a result, teachers can make informed decisions when devising materials. Likewise, another important aspect of MD is the practical undertaking that can be seen as the outcome of the systematic process of production, evaluation, and implementation of materials (Tomlinson, 2001, p. 66).

2.2.1. Material

According to Tomlinson (2011), material can be defined as “anything which is used to help language learners to learn.” (p. 2), and Xiaotang (2004) also adds that “materials are not just tools; they represent the aims, values, and methods in teaching a foreign language” (p. 1). In that way, materials are a key factor to match the real students’ needs and wants with the language learning process. In fact, materials must be presented in diverse ways; they can cover all students’ dimensions and skills. For that reason, before designing a material, teachers should decide if they want a material focused on instructional, experiential, elicitation or exploratory purposes to fulfill students’ expectations (Tomlinson, 2011, p. 2).

Teachers play an active role in materials development since they are responsible for transforming the language learning process through the creation of their own materials. As a matter of fact, teachers are the ones who have greater knowledge about the student’s interests, needs, wants, and context, so they can use this information to facilitate the learning of L2. In that way, the fact that teachers develop their own materials can also draw some advantages for them. These benefits identified by Holguin & Aguirre (2014) are “teachers’ empowerment, an increase of students’ motivation, the need to listen to students’ voices to consider their needs and the requirement of contextualizing teaching materials” (p. 3). Having that in mind, the process of developing materials can lead teachers to a reflective teaching process that continuously favors the experiences of the language learning process in diverse ways.

2.2.2. Materials evaluation

As Tomlinson (2013) explains, materials evaluation is “a procedure that involves measuring the value (or potential value) of a set of learning materials” (p. 21). So, there is a need for teachers to become materials evaluators to analyze if ELT materials suit the student’s needs and teaching objectives taking into account some criteria, in order to evidence the outcomes of materials on the learners. In fact, the criteria can be constructed from principles of SLA (Second Language Acquisition) and assertions, beliefs, and perceptions that teachers have articulated towards their English Language Teaching experience. As a result, they can use this matter for future selection.

Materials evaluation can be developed in different phases: pre-use, in-use, and post-use. The first one refers to the previous prediction that teachers made to value a material, the second mentions the description of the current use of materials by learners and the last is related to the examination of the impact that the materials had on the learners (Tomlinson, 2011, p. 14).

2.2.3. Materials adaptation

Material adaptation is a result of materials evaluation since it involves changing objectives, topics, activities, and sequences in a given material to make it more significant for learners. For instance, in the Colombian context, it is common that the national government provides a series of English textbooks in public schools to support the English learning process, so teachers tend to adapt this given material depending on the student’s needs and interests since they realize the ELT materials do not fulfill the teaching objectives.

According to McDonough et al. (2013), there are some techniques that can be used to adapt materials such as “adding, deleting, modifying, simplifying and reordering” (p. 70). Those can be applied to language practice, texts, skills and classroom management. Also, Maley (1998) contributed with other options to adapt materials such as omission, addition, reduction, extension, rewriting/ modification, replacement, reordering and branching (pp. 381-382).

2.3. Differentiation inside the classroom

Differentiation strategies can be defined as the ways teachers respond to the needs of their students. At times, students don’t have equal readiness to learn the same topics simultaneously, which can be due to many reasons, such as variations in the brain development of the learners, or gaps in their learning because of their previous education quality (Dial, 2016). For these reasons, some students may be at a disadvantage, as they are not prepared to gain the knowledge required by the syllabus for their grade; even if students are around the same age, their readiness to learn, and their learning styles and pace will differ. Hence, teachers should be prepared to support and help their students by taking into account these aspects and by understanding students as individuals with different abilities, and backgrounds inside the classroom. There are three curricular elements that teachers deal with when it comes to structuring differentiation in the classroom: content, process, and product (Dial, 2016).

2.3.1. Content

What is taught and what teachers want students to learn is referred to as content, and this can be differentiated in two ways: adapting what professors teach, and adapting how students access what teachers want them to learn (Tomlinson, 1995). For adapting what to teach, teachers may instruct

some students to work on a topic, while the other students proceed with a different one. For adapting the ways to access the information to learn, a teacher may teach the same things to all students, but he or she will use different ways of approaching the topic. To illustrate, in a class with low-intermediate and advanced students, the former group could learn basic uses for the modal verbs, while the latter will learn more difficult uses.

2.3.2. Process

Process concerns the way students make sense of ideas and information; how they understand their learning (Dial, 2016). This contributes to a process of metacognition, in which students receive new information and compare it to previously acquired knowledge. For this process to be differentiated, teachers will have to use activities that, as Tomlinson (1995) states, are “designed to help a student progress from a current point of understanding to a more complex level of understanding” (p. 79). In other words, there is a need for scaffolding inside a classroom to make it differentiated.

2.3.3. Product

As stated by Dial (2000), “products can be equated to summative assessments” (p. 103). This can be understood as the final activity that will measure students’ understanding of the recently gained knowledge and how they have fulfilled the standards the teacher had previously set in the syllabus. Nevertheless, teachers should take into account some components to design an effective product, such as: distinguishing what students should know (facts) or be able to do (skills); determining the expected quality in content (information, concepts), process (planning, defense of viewpoint, research) and product (size, construction, durability, expert-level expectations, parts), and deciding on how to scaffold by using brainstorming or developing rubrics (Tomlinson, 1995). With this in mind, teachers will be able to design an assessment that will work as a product and recognize how the differentiation in content, processes, and products can impact their classroom.

3. Methodology

The type of study of this article is qualitative research. McCusker & Gunaydin (2015) state that “qualitative research is characterized by its aims, which relate to understanding some aspect of social life, and its methods which (in general) generate words, rather than numbers, as data for analysis” (p. 1). In fact, it allows flexibility when it comes to exploring questions with the participants. Furthermore, this is a phenomenological research which explores teachers’ knowledge on the development of materials in diverse educational spaces in the Colombian context. As Neubauer et al. (2019) described, “phenomenology is the study of an individual’s lived experience of the world” (p. 93). That is why analyzing a situation as it is individually lived allows us to create new interpretations and perceptions that can reframe how we comprehend that experience in new ways.

3.1. Context of the study

This research was conducted in Pensilvania, Caldas, a rural region in Colombia, where there were only two high schools: one had complementary pedagogical training and the other was a traditional school. For this investigation, the population consisted of 6 teachers from both schools; most of them held a bachelor’s degree with an emphasis on English teaching, but there were two teachers that acquired the L2 empirically; these participants were chosen as their unique educational focus is English Language Teaching (ELT). Therefore, we wanted to have evidence of their experiences regarding the strategies of differentiation they implemented when developing materials.

3.2. Data collection techniques

The techniques that were used for data collection were semi-structured interviews and class observations. Regarding the first one, these types of interviews offer interviewers to prepare questions ahead, and interviewees have the freedom to extend their views if necessary. Also, this type of interview allows for open-ended questions, which as Mathers et al. (1998) state “provides opportunities for both interviewer and interviewee to discuss some topics in more detail” (p. 2). For the second data collection method, the observations were used as it could grant us first-hand information to collect; besides, this instrument “has the potential to yield more valid or authentic data than would otherwise be the case with mediated or inferential methods” (Cohen et al., 2018, p. 542). In brief, the techniques used previously permitted us to describe what was happening in the classroom in detail, since it led to understanding the teachers’ and students’ reality, as well as the reasons for the issues presented.

The observations and interview recordings data were then transcribed and translated into English by the authors. The information was analyzed taking into account the patterns, such as the similarities and differences found. After finishing this process, the data was horizontalized to create equal-value categories to organize the common data in groups (Moustakas, 1994, p. 98) by taking into account the most important aspects of the interviews.

3.3. Instruments

The research project was presented to our population through an informed consent form with a concise summary of the research. This description included the research question, objectives, instruments, and ethical considerations. Subsequently, class observations and interviews were held face to face over 1-2 weeks; the interviews were conducted in Spanish, the first language of the participants, with 10 open-ended questions. Moreover, the class observations lasted between 45 and 60 minutes each, and most of them were in the form of a group activity that involved around 20 to 25 students in each group. However, there was only one group that had approximately 12 students. The fact that the group sizes were big (twenty to twenty-five pupils in each) makes a considerable contrast towards the differentiation elements of the phenomena observed.

4. Findings

The information was gathered and clustered taking into account the objective of this investigation, which is to identify the use of differentiation strategies in rural classrooms, and the main question is how teachers implement differentiation strategies through materials considering the different students’ profiles. For this purpose, the instruments used to analyze were observations in every English class and interviews of each teacher, this population of 6 teachers from both schools in the town. In that way, the differentiation was reflected in the teachers’ points of view.

In the following section, the interviewed teachers’ perceptions about differentiation will be covered through four (4) main categories, which are the following: implementation of differentiation, considerations about materials, creating/designing and adapting materials, and material differentiation inside the classroom. (Table 1)

Table 1 Interview questions classified inside the research findings categories

| Categories | Interview Questions | Excerpts |

|---|---|---|

| Implementation of differentiation | • What is differentiation, and how is it implemented? | ‘‘I consider differentiation can be discovering different types of abilities’’ (Teacher J. G) |

| Considerations about materials | • What do materials mean to teachers? | ‘‘For me, materials are an aid, a tool to be able to carry out a dynamic class’’ (Teacher Y) |

| • What training have teachers had around materials development? | ||

| • Do institutions offer didactic materials? What do they offer? | ||

| Creating/designing and adapting materials | • Do teachers design material for their classes? Why or why not? | “the material that is very visual, that catches the students’ attention, and according to the difficulty level […], easy to work so they get some fun at the same time, and so they enjoy what they’ll be working on” (Teacher L) |

| • What do teachers take into account | ||

| when creating/adapting materials? | ||

| • Do teachers use the materials offered by the institutions? | ||

| Material differentiation inside the classroom | • Do they differentiate with materials? | ‘‘No, I treat each of the students according to their level, I try to demand them. However, one as a teacher realizes that some student finds it difficult to develop an activity but I never make a differentiation in a workshop’’ (Teacher P) |

4.1. Implementation of Differentiation

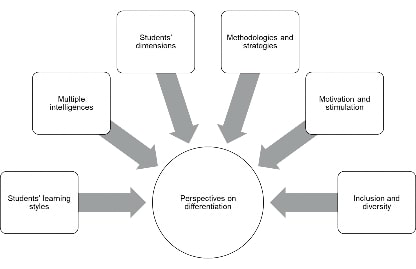

The first category identified from teachers’ interviews was the differentiation approach. In order to better understand the different perspectives, participants were asked to define what is differentiation for them, and the majority of them agreed with the main components of this concept (see Figure 1). Therefore, it is evident the emphasis on developing responsiveness to students’ needs, which aims to recognize the variety of learners’ profiles inside the classroom to integrate successful learning and teaching practices.

These findings are in accordance with Pham (2012), who defines differentiated instruction as “the identification of student readiness to help teachers deliver lessons in an effective manner” (p. 18) Having this in mind, the fact that the differentiation approach involves structure content, process, and the product is important to mention that Teacher J. G. made a great contribution to clarify how he differentiated by modifying the content. In the following excerpt, he explains deeper how the process of differentiation in content is:

(1) To make differentiation we have a document called PIAR is an Individualized Plan of Reasonable Adjustments (PIAR Plan Individualizado de Ajustes Razonables), in which the curriculum is modified for students who have been diagnosed with special needs, exceptional talents or learning difficulties taking into account the basic learning rights (DBA) is analyzed what is the minimum of basic skills to be acquired and adjusted, in this way we can help them in their learning process, making observations periodically. (Teacher J.G.)

The aforementioned explains clearly how differentiation is made in Colombia, since the decree 1421 talks about the inclusion process. According to the MEN (2017), public policies were created to foster the right to equality of people with special needs by taking “necessary and appropriate actions, adaptations, strategies, supports, resources or modifications of the educational system and school management, based on the specific needs of each student” (p. 16). Therefore, rural schools can guarantee students’ autonomy by overcoming limitations in the classrooms using this tool. Indeed, one of the teachers (J. G) found a common challenge in rural classrooms, which is the number of students inside a classroom around 30 or 40 and this makes hard the process of monitoring the students’ process periodically because the teacher has to manage the classroom at the same time he analyzes the barriers they present. This is backed up by Tomlinson (2000) as she states that “teachers who offer a single approach to learning, teachers who differentiate instruction have to manage and monitor many activities simultaneously” (p. 2). Therefore, it is essential to make adjustments to the curricula and syllabus to achieve effective differentiation despite the challenges.

In addition, the same teacher described the process of how he does differentiation inside the classroom. The following is an excerpt from the interview:

(2) What I do is like teaching the basics, if I have a class about the present simple and I have a text about interpretation, what I do with them is focus on vocabulary, on words, [so I say] let’s differentiate the vocabulary, the pronunciation or let’s draw a little picture like a landscape, where they can express the basic vocabulary from that topic (daily routines). Then, I only explain an image with the action, not like reading, not like answering a question because they don’t have the ability to answer it or ask questions. (Teacher J.G.)

Previously, it was noticeable the use of adaptation strategies such as omission proposed by Tomlinson because J.G decided to only focus on vocabulary since it was more relevant for this student’s needs and also he planned strategies for the student to understand the concept by explaining an image with actions as he analyzed this student was bodily-kinesthetic, also he defined what he expected from him by recognizing it is the basic ability he/she could achieve. As Ortega et al. (2018) pointed out, modifying the process “involves employing distinct activities, tasks, teaching techniques and strategies aimed at helping students obtain the new learning” (p. 1222).

4.2. Considerations about materials

The second aspect discovered in this research was the considerations given by the teachers about what materials mean to them. They all agreed that materials are a tool to facilitate the learning process in order to make it entertaining and apprehensive. As well as it is mentioned by Tomlinson (2011), who defines materials as ‘’anything which can be used to facilitate the learning of a language’’ (p. 2). Taking into account that it can be developed in different formats, such as: visual, auditory, or kinesthetic, in order to fulfill a pedagogical objective.

In addition, they were asked if they have taken any teacher training course throughout their life about materials development, to which they gave mixed responses since some did receive this type of training and others simply learned “on the way” (through the teaching experience) as one of the teachers interviewed said. According to Tomlinson (2011), what really matters in a material development course is its quality. However, the value of these materials depends on how well teachers know their students and how meaningful the implementation is in class.

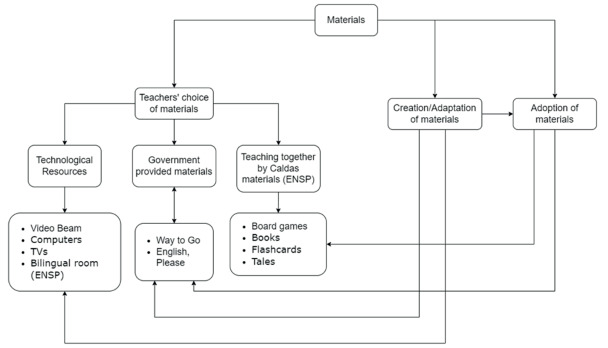

Teachers were also asked if the institutions provided them with materials. Here, it was found that one of the educational institutions does provide materials such as games, books, f lashcards, audio, tales, and more didactic resources, as they form part of the Teaching Together by Caldas program. Nevertheless, the other public school in the town is only provided with dictionaries and the Government’s National Bilingualism Program books, such as “Way to Go” and “English, Please”. Teachers also wanted to include technological devices such as TVs, computers, and Video Beams in this list of resources. These were some of the teachers’ answers related to this category:

(3) I really like digital material. There is a bilingual room, but there are several computers that are damaged, or there are problems such as some missing mice, etc. So I have preferred not to use it this year because, otherwise, I would have to pay for that [damaged equipment]. (Teacher J)

(4) In the classroom, I sometimes try to implement these types of tools such as the video beam, vocabulary games, or videos that can help them with what one does in class. (Teacher J.G.)

(5) Well, the institution has texts that I use in class as didactic material, we also have colored posters. [Materials] can also be the use of computers, TVs are also a medium [of instruction].and the institution provides them. (Teacher L)

(6) Public institutions do not have much didactic material to offer. Usually, one has to make it. (Teacher D)

As evidenced above, both institutions provide teachers with different materials in order to do dynamic classes. However, through the practicum experience, it was demonstrated that those materials are not available equally to all English teachers due to the poor conditions and the small number of technological devices found in the institutions. For this reason, some teachers decide to create and bring their own teaching materials to the school, such as the video beam, computers, prints, flashcards, etc, in order to provide a dynamic class to their students.

4.3. Creating/designing and adapting materials

The third aspect focused on in this research is how teachers created or adapted materials. Teachers also shared their considerations when adapting or creating materials, and their experiences with these processes. Furthermore, they were asked whether they designed or made any kind of adaptations. According to their answers to that question, the next thing to be asked could vary, but it would follow the line of asking what they took into account to create or adapt the material.

The following are some of the teachers’ answers to the interview questions associated with this category:

Q1: What do you take into consideration when creating/adapting materials?

(7) The students, their levels, and their attitudes, as some of them, don’t have a good attitude towards English. (Teacher Y)

(8) That the material is very visual, that it catches the students’ attention, and according to the difficulty level […], easy to work so they get some fun at the same time, and so they enjoy what they’ll be working on. (Teacher L)

(9) The type of population I’m working with, that catches their attention. I mean, one has to program things in accordance with the interest to whom I’m selling products, and the product one sells is education. (Teacher D)

As shown above, it can be said that what most teachers consider paramount when it comes to materials creation and adaptation is students. As Tomlinson (2014) said, “Learners only learn what they really need or want to learn” (p. 175), and as our observed teachers’ students were high-schoolers, there was not a need for them to acquire English just yet. Therefore, learners saw learning English as an imposed process, which did not motivate them to keep learning; teachers were highly aware of this information, as the answer from Teacher Y shows. Therefore, they were more likely to try to find materials that “catch their attention” as if we were trying to sell a product (Teacher D).

(10) Furthermore, it was discovered that, for creating materials, certain teachers do engage in the process of creating materials from scratch. This is a result of them not finding suitable materials to use with their students because of specific reasons, such as materials not catering to their students’ English levels, grades, preferences, or the learning purpose of the lesson; in other words, they develop materials when they cannot find compatible and usable materials. Sometimes, they would develop materials if the classes were small in the number of students, as this answer from Teacher Y shows:

I developed an exclusive material for a level. I had to create an English book in which I had to include the themes we were going to work with, add images, a short explanation, and the exercises students had to develop. […] I used this book with pre-school, it was really as well, just completion exercises, and the drawing the kids had to paint. Also, as the quantity [of children] was small, it was even easier.

Nevertheless, even when material creation was a focal point in the interview conducted, during the class observations almost no teacher used materials created by themselves; only teacher L prepared a short worksheet for students to work on. As a matter of fact, this worksheet was a mix of many already existing materials that she put together. In another class, one teacher decided to use music videos to provide motivation from the start of the class, and so students could ‘know’ what the lesson was about, which could be understood as an adaptation of authentic material. From this set of data (observations), it was concluded that most teachers prefer adapting, or ‘adopting’ materials.

As it is known, adapting materials may refer to modifying the contents, sequencing, the format and presentation, or the monitoring and assessment (Macalister, 2016). In this process, teachers need to consider some aspects like students’ English levels, preferences, and the purpose of the lesson as well. Furthermore, with the plethora of existing materials out there, teachers need to be selective with what they intend to include in their classes, and this requires setting up the criteria for selection such as effectiveness, appropriateness, and teachers’ objectives (Marand, 2011).

However, apart from the scenarios mentioned before, it could be evidenced that teachers did not do much adaptation, but rather adopted already existing materials. Hence, they did not adjust or modify the materials and only used them. Still, this process continues to require consideration of key factors such as students’ needs, environments, and goals, but this is the preferred method as it is less time-consuming.

(11) [...] adapting their material [...] but it’s a process that takes time. (Teacher J.G.)

Additionally, teachers were asked if they did any type of adaptation to the materials the schools provided, these are some of their answers:

(12) Yes, I usually try to use what the institution provides and I show the students. [And the use of this material] That speeds up the time. (Teacher P)

Nevertheless, another teacher (Teacher D) answered that she does not use materials, such as the books previously mentioned (“Way to Go” and “English, Please”), because she does not like them. Yet, she did follow the content of the books, adding the topics as part of the curriculum in the same sequence that they appear in the books.

Accordingly, during the class observations, it was evidenced by the adoption of materials, so no adjustments or modifications were made before presenting the materials to students, be they digital or physical resources. As shown in the diagram below (Figure 2), adaptation and creation of materials did occur when employing technological resources such as video beams, TVs, etc., and when using the government-provided English textbooks. Moreover, adaptation and adoption took place for the utilization of the materials provided by social institutions such as the national and local governments.

Furthermore, teachers implemented differentiation strategies, but they did it in the classroom while presenting the content of the class, in the way students accessed this content, during the activities, and in the way they assessed. This is explained in the next category.

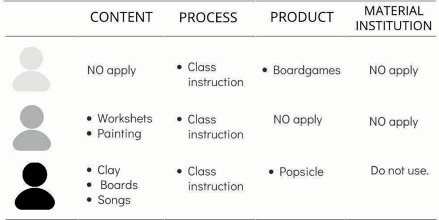

4.4. Material differentiation inside the classroom

The last aspect of these findings was material differentiation and it was the most important aspect for this research because the teachers let us know how they implement differentiation strategies through materials taking into account their students’ cognitive profiles, which is the main focus of our investigation. Some teachers adapted the content of the material in a dynamic and creative way, for example, in the observation class it was evidenced that “teacher D” used three (3) different types of materials: clay, mini boards, and songs, and motivated the student participation with sweets, so students with different cognitive profiles could enjoy and learn just like their other classmates. Other professors modified the presentations and gave their exceptional students different worksheets from the rest of the class for students to participate in, as “teacher L’s” class noted her effort in creating differentiated material for certain students which is easier for them to acquire knowledge.

As a matter of fact, many of the teachers clarified that they did differentiate on the process during class instruction, and it was significant to them to provide clear instructions as this teacher states: “to provide clear information to my students and explain the activities to make it easier for them” (Teacher Y) because students can receive and associate the knowledge even when each one of them learns from different ways. According to Zólyomi (2022), “the key to addressing learners’ profiles is in the teacher’s flexibility to employ various teaching methods so that the students have an increased opportunity to receive instruction in their mode of learning” (p. 16). Thus, they would teach all students the same topic or theme, and use different approaches to make sure most students understood. Meanwhile, teachers considered different aspects to apply the product and evaluate their students, such as “teacher Y” who adapted a board game and, knowing the abilities of her students, also intensified it and evaluated their knowledge. Furthermore, to encourage students to express what they have learned in varied ways, “teacher D” uses popsicle sticks in a dynamic way to be careful about the learning process.

On the other hand, other professors specified that they did not need to make any adaptations to the class material. As an illustration, one of the interviewed teachers states: “I treat each of the students according to their level, I try to demand from them. However, you as a teacher realize that some students find it difficult to develop an activity but I never made differentiation in a workshop” (Teacher P). For this reason, teachers fail to adapt the pace of instructions in response to learners’ needs, with the result that many students of varying readiness levels feel frustrated (Ben Ari & Shafir, 1988). Perhaps for some students, this becomes a challenge while others will feel very unfulfilled for not understanding and learning at the same pace. I don’t don’t

Taking into account the materials that the institution provides to teachers as support for the teaching of English, they analyze and do differentiation with the correct material before implementing it, as a teacher is cleared: “the material must be read and broken down”. (Teacher P). Also, another teacher specified the following: “There are dictionaries in the library, I tried to implement them because in my classes they use the dictionary, they know how to use it, searching for words was identified by many of the team” (Teacher J.G.) Unfortunately, the same teacher affirms the following: “This material is scarce, they cannot be scratched or anything, one uses them at the moment and they transcribe” (Teacher J). In addition, this could be a problem in the student’s learning process.

Furthermore, this teacher spoke about her experiences saying: “I tried different things with the students and analyzed what material works and catches the student attention, I deal with a word search or crossword puzzle, or another student can use the computer with a specific resource, or the student is going to do the same activity but only paint” (Teacher L). Just as there are teachers who take the time to adapt the material that institutions provide, there are others who do not do it. For example, Teacher D was very clear when she said: “I don’t use the books, I don’t like them. I follow the program, but I don’t use the books”. Doing the process in a different way does not mean that it is wrong, on the contrary, the material can be innovated, and better teaching dynamics can be developed in the classroom. (Figure 3)

5. Conclusion and pedagogical implications

The objective of this study was to explore how the Colombian teachers from Pensilvania, Caldas, implement differentiation strategies in their classes using materials and considering the different students’ profiles and the number of students they have in each group. Primarily, it can be stated that the population of this investigation (teachers) alleged that they do not have sufficient knowledge about differentiation, so they do not engage with a major level of differentiation in their classes. This is evidenced in teacher P’s answer to a question related to her experience working with students who have different cognitive profiles: ‘‘I consider that to work with these types of students you must have a certain type of study. I mean, I have a degree and, in my career, teachers never told me that maybe in my classroom I would find students with [for example] vision problems. They always spoke to us in general terms and when one arrives for the first time in a real classroom, one says ‘oh, my god. What do I have to do here?’ […] I think this is a challenge for one as a teacher in any area.”. This is a consequence of the little training related to the use of materials they have had surrounding the work with students who have different cognitive profiles, and the need for more appropriate support by schools and governmental institutions; as one of the interviewed teachers answer to the question “What training opportunity have you had around the development of educational materials?” shows: “No, I don’t really have any type of training, only the one from university as a graduate, and the experience makes me have another perspective regarding what type of material could be used, but that is very empirical”. Therefore, teachers have found making differentiation a challenging task, one that requires too much time to ponder, prepare and implement.

Also, these schools take for granted that they can manage their students without previous training or enough support. As one of the teachers expressed: “There are a series of activities that the inclusion teacher, the inclusion consultant, provided to us. She gave us a short training, but we don’t really have a professional formation that emphasizes inclusion with students who have specific needs” (Teacher J. G.). As can be seen in the teachers’ response, they may be given some resources or support, but they are not sufficiently trained. However, it can be said that even when teachers have not had sufficient training in this area, they are still attentive to students’ needs. In this way, they want to have fun and pleasing classes by using engaging materials that can catch all students’ attention.

It should be noted that the purpose of sharing the findings of this research is not for teachers to start implementing differentiation strategies in every class with every group of students, but rather to analyze how this process of implementation was taking place inside classrooms with students as different as they are alike. Therefore, we want to raise awareness of the differentiated instruction used by the English teachers that accepted being part of the study, and with this, we call for more training and professional development on differentiated instruction, so teachers can implement it effectively; also, with this proper coaching, they would be able to assess students’ needs in a more effective way. Thus, teachers with this knowledge could prepare efficient classes and materials for students with different learning profiles, which would lead to more significant education for these groups of rural students who have had to “make do” with what has been provided to them.

There are a number of limitations in this study as well. Firstly, there could have been more time for data collection, as the findings described in that section are only the result of a three-week gathering from which we could manage to do 6 interviews (one of which was not completed), and 6 class observations. Another limitation may be the interview fragments used, as there could be relevant information left out that was not in line with our categorization or purpose. For the reasons listed before, further research is needed to keep analyzing differentiation practices in other rural and urban areas from Colombia. Certainly, having more time to conduct more interviews and class observations could be beneficial, as well as being able to go through the preparation of differentiated material with the teachers, and having copies of their differentiated material in order to analyze it in depth. This would add more understanding to how differentiated instruction has been taking place in rural classrooms. Still, this study has provided thoughtful insight into rural teachers’ beliefs and knowledge of the implementation of differentiation. Furthermore, it could be also recommended to investigate how pre-service teachers have implemented differentiation in their practicums in accordance with their studies and inspect if today’s teacher training has a greater focus on teaching in diverse classrooms and contexts.

However, we would like to finish by thanking the teachers who took the time to participate in our study. We appreciate and value, not only theirs but all the work that rural teachers must do, as they have to take charge of large classrooms with 30 to 40 students, who may have extremely different cognitive profiles. Even if the differentiation is not done in a fuller measure, they still try to include everyone in their classrooms. For that reason, we should be aware and there should be better visibility of these laborers and more appreciation of these teachers that, day by day, have to face all kinds of situations that not many would be willing to confront.