1. Introduction

In the globalized dynamics of today’s world, English as a Foreign Language (EFL) has increasingly gained relevance as it has progressively made it to the heart of economic, politic, and technological communication in physical as well as virtual-mediated interactions (Alfarhan, 2016; ChávezZambrano et al., 2017; Nishanthi, 2018). That relevance, in turn, has increased the interest for the acquisition of communicative competence in EFL at all levels of education, and in different domains of social life and spawned the creation of bilingual education programs and resources for such an end (Alfarhan, 2016; Guri, 2017; Köktürk et al., 2016). Developing communicative competences to become proficient in EFL; however, has always posed challenges regarding the type of communicative environments that could be conducive to EFL learning. To further complicate matters, the COVID-19 pandemic forced a rapid transition from on-campus, face-to-face classes to virtually-mediated instruction. This transition to virtual-mediated instruction and the affordances and limitations for communication therein has direct implications for social interaction, student engagement, and agency and hence, for learning (Bird et al., 2021; Escobar-Almégica, 2020; Escobar-Alméciga & Brutt-Griffler, 2022; Mahyoob, 2020; Norton, 2013).

This underscores the need for an evaluation of such virtual-mediated conditions for learning given that learning results from the negotiation of meaning and the construction of knowledge in social interactions where communication, cooperation, and participation are at the core (Fairclough, 2011). Communication, in turn, entails far more than just the spoken language. Rather, it incorporates numerous semiotic resources and communicative modes, like gaze, gestures, images, color, layout, proxemics, etcetera, in meaning negotiation and knowledge construction (Norris, 2004). That is to say that a learning environment is a multimodal communicative environment (Escobar-Almégica, 2020; Escobar-Alméciga & Brutt-Griffler, 2022). Thus, the designing of communicative environments that empower students to act on their own behalf, and in pursuit of their individual and collective interests should be at the core of instructional designs and implementations (Escobar-Almégica, 2020; Escobar-Alméciga & Brutt-Griffler, 2022; Kress, 2011).

As such, this research seeks to assess technology-mediated communication in the EFL classroom in Higher Education (HE) and its implications for student investment, agency and, ultimately, for learning. The question guiding this study is as follows: what implications does technology-mediated EFL instruction present for student investment, agency, and, ultimately, learning as an effect of communication?

To embark in such an undertaking, we laid a theoretical platform which provides general notions on the connection between communication and learning. Subsequently, we addressed the issue of online interaction through a Multimodal Interaction Analysis (MIA) as depicted by Norris (2004), which led us to conclude that learning is a result of the type of interaction and communication that empowers students to act on their own behalf and that encourage them to resort to their own semiotic resources to negotiate meaning, ideas, emotions, identities and so on.

2. Theoretical framework

Understanding that learning is configured in social interactions, this section is devoted to explaining how communication is multimodal and the ways in which semiotic resources act and interact in the negotiation of meaning and the construction of knowledge. As such, we explore the concept of multimodal communication and its intricate relations to investment, agency and learning in a VLE.

2.1. Multimodal communication and a social interaction approach to language learning

New technological advances have given rise to alternative forms of communicating from a distance, for example, breaking the geographical, time, and transportation constrains that people from different locations would normally have for interaction. Such advances served as platform when it came down to facing the distancing regulations that the pandemic brought about for society in general and for education in particular which rushed us to a sudden migration to online education. As all communication, virtual-mediated interactions rely on an enormous array of semiotic resources and communicative modes for meaning making (Norris, 2004; Pan & Block, 2011). However, given the historical circumstances, it is of our particular interest to inquire about learning as an effect of communication when communication is being mediated by such technological advances.

That is to say that people are immersed in social dynamics where they come in contact with others in many different ways and at various levels and exchange ideas, stories, histories, cultures, identities, knowledge and discourses. Such an exchange happens in the interplay of an infinite number of semiotic resources and modes which, in turn, make possible the negotiation of meaning, the construction of knowledge, and the creation and interpretation of realities (Escobar-Almégica, 2020; Escobar-Almeciga & Brutt-Griffler, 2022; Fairclough, 2011; Norris, 2004). In this sense, communication is at the heart of human life as it forms and transforms personal and collective views, beliefs and idiosyncrasies that frame and re-frame realities in different domains of social interaction (Escobar-Alméciga, 2020).

More precisely, communication holds a direct and reciprocal relationship with learning where learning comes as a result of the communicative possibilities afforded to students in and by a particular communicative environment. Edifying communicative possibilities, in turn, are possible when a respectful, supportive, and inclusive classroom climate is created and students are empowered to resort to their own historical, intellectual, social, cultural and emotional-semiotic-resources to act in pursuit of their own learning (Escobar-Almégica, 2020; Fairclough, 2011; Gee, 2011; Kress, 2011). While classroom interaction has been extensively researched in EFL educational contexts (Asbah, 2015; Gardner, 2019; Zhang & Gao, 2020), how these interactions happened in the particular public health emergency where instruction was technology-mediated is still a research opportunity that could potentially contribute to the evolution of virtual education in general and virtual EFL instruction in particular.

2.2. Investment and agency in EFL learning

Learning a foreign language takes more than just learning the grammar; it also entails learning about the culture to use the language effectively in various situations (Norton, 2015). Language learners need to acquire culturally representative and symbolic resources that allow them to negotiate meaning, exert communicative action, and navigate the social systems they live in to develop such pragmatic competence (Bourdieu, 1991; Huamán Rosales, 2021; Hymes, 1967, 1974, 1979; Norton, 2013). Learners actively participate in the pursuit of social goods, the development of relationships, and the accomplishment of academic goals as invested individuals motivated by their own agency or desire to act on their own behalf and achieve their goals (Knight et al., 2017; Norton, 2013). In this sense, language learners work to participate in social exchange that unavoidably shape their discourses and identities in their own unique ways (Gee, 2011; Newmann, 1989, 1992; Norton, 2013; Saeed & Zyngier, 2012).

However, student involvement and agency in this endeavor are greatly influenced by the teacher’s discourse. Students’ capacity to act independently and learn effectively can either be facilitated or hindered by the teacher’s words and deeds, as well as the discourses, attitudes, and behaviors encouraged in the classroom (Aukerman et al., 2017; Escobar-Alméciga, 2020, 2022; EscobarAlméciga & Brutt-Griffler, 2022). To promote student investment, instruction should prioritize the creation of safe, welcoming, and engaging communicative environments in which students feel free and empowered to express their ideas, emotions, and identities (Bourdieu, 1991; Brown, 2014; Darvin & Norton, 2015; Escobar-Alméciga & Brutt-Griffler, 2022). Such environments should encourage students to implement their sociocultural, emotional, intellectual, and historical resources to act and interact in the contexts they find themselves in.

Both students and teachers can collectively pursue the ideal social classroom conditions for successful language learning and the development of the learners’ communicative competence by creating a sense of entitlement to use their own semiotic resources freely, naturally, and purposefully (Canale & Swain, 1980; Hymes, 1972; Littlewood, 1981; Savignon, 1987). That is to say, for students to succeed academically and be able to effectively communicate in a variety of social contexts, they need to be socially invested and exert agency in pursuit of their learning and social objectives.

3. Method

This is a qualitative case study of a group of sixth semester students at a university English languageteaching program (Creswell, 2007; Merriam, 1998). Therein, we analyzed the students and teacher’s interactions and the way such interactions could shed light onto students’ investment and agency. We also sought to identify the affordances and limitations that this communicative environment presented for creating learning opportunities for students guided by Norris’ (2004) interaction analysis framework.

The research took place in a private university located in the north end of Bogotá. More precisely, it took place in an undergraduate bilingual education credential program where English was used as a medium of instruction for many of the content areas. The program, in turn, had six intensive English courses aiming at taking the students to a C1 proficiency-level according to the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR).

Upon the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic in the context, these courses were rapidly migrated to a VLE where the teacher and students used a virtual platform and videoconferencing tools for the teaching and learning processes. They had both synchronous and asynchronous sessions designed and guided by the teacher.

All 32 class sessions were video, and audio recorded for a total of 40 hours of class recordings. A preliminary analysis sought to identify quiet moments where the students were working individually, preparing for a task, or reading silently. We excluded such instances from the focus data given that they were not illustrative of investment and agency in the class interaction reducing, thus, the video recordings to 12 hours. We also conducted an end-of-the-semester interview on the teacher with the purpose of gathering her perceptions, feelings, and ideas about the students’ investment and agency in the course (Buriro et al., 2017). Finally, we worked with the participants in a focus group. This focus group had the main objective of discussing, constructing, and reconstructing their perceived experience concerning their own investment and agency in the course (Kitzinger, 1995).

3.1. Data Analysis

The analysis in this research sought to recognize and understand the ways in which the participants configured, formed, and transformed the negotiation of meaning in social interactions and the extent to which this was conducive to student investment and agency in their learning process. Bearing this in mind, the analysis of data was carried out in two stages. A first stage was devoted to examining the interactions and a second stage was devoted to analyzing the contents of the interview and the focal groups to corroborate our assertions.

For the first analysis cycle, we took Norris’ (2004) list of communicative modes as a priory code to examine the way in which these modes happened or failed to happen in class communication. The following table illustrates these initial codes. (Table 1)

Table 1 Mode-code explanation

| Code | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Gestures | Body movements that convey meaning |

| Speech | Talk |

| Gaze | The way eye direction indicates communicative actions. |

| Posture | The way body positions indicate communicative actions. |

| Layout | The way and the organization, of people, places, and visual representations convey meaning. |

| Head Movement | The way individuals position the head to convey meaning. |

Note. Escobar-Alméciga (2020, p. 89)

In this regard, Norris (2004) asserts that the collective processes of meaning making in interaction relies on-beyond speech-a multiplicity of modes. As such, this first analysis sought to examine the semiotic resources that the class participants employed and the modes in which they deployed them in their interactions (Escobar-Alméciga, 2020; Escobar-Alméciga & Brutt-Griffler, 2022). It also accounts for the prosodic elements of spoken language like emphasis, pauses, and silences using the method of narrow transcription proposed by Norris (2004) as follows (Table 2):

Table 2 Spoken language transcription conventions

| Transcription conventions | |

|---|---|

| Spanish Utterances | in italics |

| Descriptions | (in parenthesis) |

| Emphasis | in CAPITALS |

| Overlap | indicated by these brackets. |

| Time | besides the participants’ intervention in parenthesis i.e. (0:00) |

| Participants | students’ first name |

| Transcript line | indicated in parentheses at the beginning of the transcript. i.e. (1) |

Note. Norris (2004, p. 72)

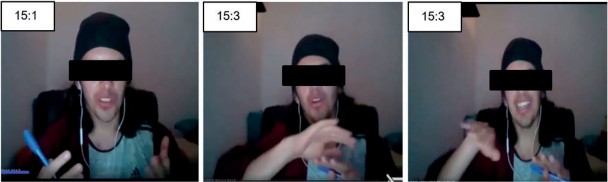

Finally, we also resorted to picture transcription (Norris, 2004) to account for interplay of semiotic resources and communicative modes during interactions as shown in the following Figure 1:

The subsequent level of analysis relied on open coding to identify investment and agency-related themes as illustrated in the following Table 3.

Table 3 A priori codes that emerged from the second cycle of analysis

| Second cycle coding | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Identity | traits subjects adopt and are produce in social sites, structured by relations of power, in which the subject assumes positions within a discourse that changes over time and space (Pierce, 1995) |

| Participation | actions that agent perform to engage in a practice (Evnitskaya & Morton, 2011) |

| Change agent | an individual whose actions promote changes in groups people and environments (Zubialde, 2001) |

Note. Self-elaboration

In a final analytical level, we looked into the patterns across the data and grouped them into three greater meaningful categorical themes: (1) discussing the influence of multimodal communication in students’ involvement in virtual lessons; (2) signs that students’ engagement was conducive to investment in EFL learning, and (3) agency evidenced in students’ participation and commitment to constructing knowledge.

4. Findings and discussion

A number of semiotic resources and communicative modes mediated the interactions in the level-six English course (communicative event). In this communicative event, teacher and students collectively co-constructed meaning, resorting to their emotional, intellectual, historical, cultural, and social (semiotic) resources to engage in class-related conversations in pursuit of their learning. As such, the findings herein provide ample insights into multimodal interaction in EFL teaching and learning processes when they were virtually mediated. Consistently, this analysis yielded four main categories, which address multimodal communication and classroom engagement, followed by the actions that led investment, agency, and the actions to promote these changes on students.

4.1. Discussing the influence of multimodal communication in students’ involvement in virtual lessons

Students engage with class contents and with each other in ways that, more often than not, go unnoticed in the traditional class dynamics (Escobar-Alméciga, 2020). Semiotic resources and communicative modes, like gaze, gestures, proxemics, performance, body posture, and body orientation, could come to represent what Fairclough (2011) calls ‘a sign’ (Escobar-Alméciga & Brutt-Griffler, 2022). That is, a learner’s action that unveils her or his semiotic work concerning communicative action in interaction. A glimpse into the ways in which s/he pursues participation and learning-often via modes other than speech-which, in turn, could potentially reveal the level to which the student is invested in what the class has to offer. Adding an even greater level of complexity, communication in VLE is mediated by technology and this restricts the semiotic possibilities that a learner could potentially have at his or her disposal in interaction and learning. Hence, inquiring about the ways in which semiotic resources and communicative modes are formed, transformed, and deployed in communication in a VLE would also exhibit signs of engagement or the lack thereof contributing to pedagogical decisions pro multimodal communicative environments within VLE. Promoting the students’ multimodal participation in VLE does not merely facilitate knowledge construction; it also acknowledges, values, and incorporates what the students bring to the classroom dynamics. It recognizes the diversity in student’s backgrounds and the infinite ways of knowing and accounting for knowledge that may, otherwise, go unnoticed.

In the particular case of the sixth-grade group, the teacher permanently prompted the students to participate in the discussions and to speak. In doing so, the teacher created a social climate in which the students were able to express their views via alternative communicative modes and semiotic resources when speech just proved inadequate in their meaning-making and meaning negotiation processes. This was especially evident when the students opened their cameras to participate, and we were able to see their body movements. It was then that the interplay of communicative modes in the collective interventions exhibited signs of the co-construction of concepts, words, and language use in general. The next excerpt exemplifies the instances in which, collectively, students co-constructed knowledge using a multiplicity of semiotic resources and modes. (Table 4)

Table 4 Excerpt 1. Teacher, Andrés, Andrea and Natalia

| Excerpt 1: Observation |

| The teacher asked her students to draw in a VLE a witch, then the students discussed their views and some concepts using EFL 1. Teacher: Your first task of the day is to draw a witch (uses the layout and waits for the students to participate) all you have to do is to draw a witch wow, ok, so let’s start identifying some common elements (…) 2. Andrés: nose. 3. Teacher: (uses gesture to agree) the nose for sure 4. Andrea: The hat 5. Teacher: (nods to agree) the hat aham (…) 6. Natalia: The smile 8. Teacher: yeah, (Uses gaze to maintain contact) like an evil smile (…) any other elements? 9. Andres: The hair is not tide? it’s always like (Uses gestures to represent frizzy hair) 10. Teacher: down like the hair is always down? 11. Andrés: no, like it’s disorganized (uses gestures to exemplify messy hair) 12. Teacher: okay, warped (…) frizzy with a lot of volume 13. Andrés: Yes! |

In the excerpt above, meaning negotiation was driven by the teacher’s request to draw a witch (line 1) which created a valuable learning opportunity for the sixth-grade group. The task of drawing a witch required the students to have semiotic representations of the concept behind the word. Such sociocultural images surfaced the conversation in intervention 2, 4 and 6 as the students began to offer differentiating features of a witch (i.e., nose, hat, and smile). The teacher was not interested in correcting the students’ production, rather, when a student could not think of a word (intervention 9), she fueled the conversation through questions that prompted a student’s gesture-based response and this, in turn, was conducive to the introduction of the word ‘frizzy hair’ (intervention 13). The sequence of questions and answers mainly between the teacher and Andrés is a sign of this student’s engagement and the role that body movement has in communication. The following picture sequence in Figure 2 illustrates the interplay of semiotic resources and communicative modes involved in the interaction.

This picture illustrates the modes that the participants used in meaning negotiation in the quest for learning. In the first sequence, students were drawing in response to the teacher’s proposed task. Then, in sequences 2 and 3, students were sharing their ideas via speech and metaphoric gestures-hand movements that represent abstract ideas (Norris, 2004). Subsequently, in sequence 4, Andrés employed Norris’ (2004) dietic gestures to represent the notion of frizzy hair. The use of additional modes of communication in this interaction enabled the teacher to support the student’s intervention offering him lexical alternatives. In sequence 5, the student repeated and provided examples using the same gesture, only this time; the teacher provided a word that accurately represented the student’s intended meaning. As such, the aforementioned actions facilitated the introduction of new vocabulary and contributed to the creation of a welcoming learning climate where the students were encouraged to resort to their own semiotic resources to participate. This particular interaction also unveiled the student’s investment toward the classroom conversation.

We can say that multimodal interactions offered ample possibilities for interpreting, understanding, exchanging, and negotiating meaning and most importantly, multimodal classroom communication promoted alternative ways of constructing knowledge and accounting for it. As such, the possibility afforded to students of communicating ideas using a multiplicity of semiotic resources and communicative modes enhanced understanding and stimulated student engagement in the classroom dynamics, which, in turn, increased opportunities for learning (Brown, 2014; Satar, 2015). This is particularly true in interactions mediated by technology where the properties of conversations are diminished by the means mediating them. As such, it is important to design virtual learning environments where multimodal communication can assist the construction of knowledge (Bezemer & Kress, 2015).

4.2. Signs that students’ engagement was conducive to investment in EFL learning

The never-ending formation and transformation of individual and collective identities take place, mainly, in interactions where people exchange, negotiate, and struggle over symbolic places in society and take on social roles that are collectively constructed and/or reconciled through discourse (Escobar-Alméciga, 2013; Fairclough, 2011; Gee, 2011; Huamán Rosales, 2021; Norton, 2015). A VLE, however, limits the extent to which the students can make use of their entire repertoire of semiotic resources and modes like proxemics, layout, gaze, etcetera., in discursive action. To compensate, the teacher promoted a welcoming, communicative, safe, and inclusive environment, and presented contents in a way that empowered students to exert communicative action in their own particular ways and in the quest for learning-agency-while endeavoring their participation and membership in the group (Krishnan & Pathan, 2013; Norton, 2013; Newmann, 1989, 1992; Saeed & Zyngier, 2012). The following excerpt illustrates the aforementioned points. (Table 5 y Table 6)

Table 5 Excerpt 2. Researcher and Daisy

| Excerpt 2: Focus group |

| Researcher: How engaged did you feel along the course of English sixth?Daisy: I think the classes were really engaging, because (…) the teacher, brought different strategies and different activities every day, so, we felt comfortable with it, (…) we tried to develop different things together that make us like, move, speak or maybe think of different aspects that we may not be used to think of, so it was really interesting, because additional to learn like the grammar and the structure of the language, we learned culture as well and that’s useful because we need to know more than just how to speak in English. |

Table 6 Excerpt 3. Researcher and teacher

| Excerpt 3: Interview |

| Researcher: What kind of strategies or content did you use to encourage your students’ participation? Teacher: I think one of the most powerful tools for encouraging participation is the variety of the activities. Therefore, the fact that we had a different topic every day of the week helped a lot with this. Some people were very active during the history-and-culture sessions (…). Another way to promote participation was the use of collaborative activities like games, brainstorming, questions, etc, also, through websites such as nearpod, mentimeter, quizizz, etc. where they can participate in real time (…) |

In the excerpts 2 and 3 above, students’ perception about their own engagement was directly associated with, first, the teacher’s use of diverse pedagogical strategies and instructional activities; second, with the opportunity afforded to students to work with others; third, with the possibility of addressing culture and history in their language acquisition processes, and finally, with class dynamics that are conducive to active and multimodal participation. The previously mentioned aspects were said to have an impact on the level of comfort students experienced and the degree to which they were empowered to participate and to exert agency in the quest for their own learning. As such, invested students are more likely to find ways to act on their own benefit with new and broader discursive mechanisms and to resort to symbolic and material resources to acquire cultural capital (Escobar-Alméciga & Brutt-Griffler, 2022; Gee, 2011; Norton, 2015).

In sum, to promote EFL learners’ investment, agency, and learning, it is important to design a VLE that promotes multimodal communication, collaborative work, and a socioculturalsensitive classroom climate. In doing so, teachers would create a communicative environment that allows students’ learning and investment to prosper exchanging and constructing knowledge while developing discursive competences (Krishnan & Pathan, 2013; Gee, 2011; Newmann, 1989, 1992; Norton & Toohey, 2011; Priestley et al., 2012; Saeed & Zyngier, 2012). That is to say, the possibilities afforded or denied to students to resort to their own semiotic resources to exert communicative action in a VLE has direct implications for identity-related processes and for learning.

4.3. Agency evidenced in students’ participation and commitment to constructing knowledge

Teachers play a central role in the creation of communicative environments, the facilitation of communication, and the exchange, the negotiation, and appropriation of knowledge in classroom interaction (Escobar-Alméciga, 2020; Escobar-Alméciga & Brutt-Griffler, 2022; Van der Heijden et al., 2018). In the specific case of the sixth-semester group, the teacher created an interactive, welcoming, and safe VLE where students had many opportunities to get involved, exchange ideas, negotiate their identities, and defend their beliefs which was, undoubtedly, conducive to the collective construction of knowledge in the communicative situations therein. The communicative action that students were able to exert in their class did not only foster the learning of contents, but it also transformed the participants’ perspectives, ideas, identities, and knowledge (Aukerman et al., 2017). This is a clear example of the reciprocal relationship that exists between the agency that teachers exercise through their instructional designs and implementations and the possibilities afforded to students to act in pursuit of their learning and their social place in the classroom community (Brown, 2014; Lane et al., 2003). Consistently, the next excerpt illustrates such reciprocity. (Table 7)

Table 7 Excerpt 4. Researcher, Andres and Daisy

| Excerpt 4: Focus group |

| Researcher: What is your opinion on the virtual classes you had on the English VI course? Andres: (…) my opinion, regarding like this environment, of course it was different from the presential ones (…) but it was interesting how this teacher Claudia, ehh was able to explore new tools and to use them in order to make it a little bit more interesting and engaging (…) we also learned about how many different ways and platforms that we can use to perform our lesson which are really interesting for us as studentsDaisy: It was really interesting because as A said, the virtual environment is really different to a face-to-face one, but also, I think that English VI course equipped us with a lot of tools, virtual tools like web tools we can use now as pre-service teachers and as future teachers, taking into account that virtuality is like here to stay, because we don’t know how long will this pandemic be, (…) it is also really useful to know that those tools that we used last semester with teacher Claudia will be useful for us to apply different activities for our future students, so it was really interesting (…) Even if it was a virtual class we were able to interact with each other |

The excerpt above illustrates ways in which the teacher’s actions brought about meaningful changes to classroom instruction and interaction. Andres, for instance, highlights the fact that technological resources come to be, in and of themselves, a source of motivation. He values the opportunity he had to see these resources being used in their pedagogical applicability in the course of his virtual English class. In a similar manner, Daisy reflects upon the role that the teacher played in forming and transforming such resources in pursuit of the teaching and learning processes and objectives. Daisy asserts that, in this class dynamics, she did not only learn language-related contents, but she also acquired useful elements for her future pedagogical career taking the teacher’s actions as model. As such, the teacher is an influence that transcends the class time and space offering academic and professional lessons for life (Lane et al., 2003).

In sum, teachers are agents of change who strive for the formation and transformation of their students by presenting them with valuable elements through meaningful experiences. We can say that the actions and strategies that the teacher implemented in the class configured communication, participation, and collaboration within the learning environment. This, in turn, offered interactive, safe, and welcoming spaces for the exchange of ideas, identities, cultures, and knowledge.

5. Conclusions

A teacher’s approach to instruction highly regulates the type of communication that students could experience in their learning environment as well as the possibilities afforded to them to find and resort to a broader repertoire of semiotic resources and communicative modes in pursuit of their learning (Aukerman et al., 2017; Escobar-Alméciga, 2020; Escobar-Alméciga & Brutt-Griffler, 2022). In the case of our sixth-semester group, the teacher promoted students’ participation presenting class contents in a multiplicity of ways and stimulating conversations. In doing so, the teacher created the conditions for students to feel safe to take risks in class interaction collectively constructing concepts, ideas, and knowledge in general. Put differently, teachers exert a type of agency that either nurtures or restricts the extent to which students can exert multimodal communicative action and their agency altogether in the class and, hence, their opportunities for learning (Lane et al., 2003).

Multimodal communication in the sixth-semester group was paramount to negotiating meaning, accomplishing communicative action, and enhancing understanding and the construction of knowledge among the group members. Students’ creativity in using different semiotic resources and modes in interaction showed their agency in transforming their social atmosphere into an environment that promoted the flow of new ideas, the exchange of knowledge, and the formation and transformation of identities (Guimarães Ninin & Camargo Magalhães, 2017). The participants did not only create a safe, welcoming, and respectful learning climate for communication in the VLE, but their interactions also offered valuable information on the ways students exerted communicative action in the quest for participation and learning during their technology-mediated conversations showing a degree investment along the way. This was made possible by a pedagogical approach that stirred away from correcting and controlling students’ responses and that, rather, focused on promoting the creative use of students’ semiotic resources and on stimulating conversations. Contents, activities, and pedagogical resources that involved the students’ cultures, identities, and knowledge moved them to engage in class activity and to find unusual ways to communicate, contribute, and participate.

That is, multimodal interactions in the sixth-grade English class encouraged students to resort to alternative semiotic resources and modes when their speech just proved inadequate for the situation at hand. Modes like gestures, posture, and head movements, worked together and complemented each other in the communicative action that students endeavored in the class. In some instances, the aforementioned modes played a central role in meaning-making while in others, they came as a complement to speech. Nevertheless, the possibility afforded to students to use their own semiotic resources and modes transformed the bidirectional student-teacher communication into multidirectional interactions where more participants were able to engage and interact with each other in one way or another. This illustrates how social interactions are at the core of knowledge construction given that it is through communicative action that learners grapple with, negotiate, struggle over, appropriate and exchange information, emotions, identities, and cultures in social encounters (Bezemer & Kress, 2015; Escobar-Alméciga & Brutt-Griffler, 2022; Evnitskaya & Morton, 2011; Satar, 2015; Vygotsky & Cole, 1978).

The use of ICT for the mediation of class instruction had a multiplicity of effects on interaction. The first and most obvious is that it connected the group members from a number of geographical locations and allowed student participation from the comfort of their homes. Second, it allowed teacher and students to use digital resources to grapple with class contents in a variety of modes that appealed to visual and auditory stimuli while enhancing understanding. Not all the effects that ICT had in the mediation of class instruction, however, were this positive. It also limited the extent to which sensory stimuli like touch, gestures, gaze, body movements, and proxemics could have a place in interpersonal interactions. In other words, even though a communicative learning environment was successfully configured, ICT-mediated communication lacks some essential properties that onsite, face-to-face communication offers.

Considering that learning is only made possible by the communicative action that students are able to exert in classroom interaction, it is imperative to gain greater understandings about the social climate for learning and to make room for the design of communicative environments in our instructional designs (Escobar-Alméciga, 2020; Escobar-Alméciga & Brutt-Griffler, 2022). That is, instruction should be embedded within a communicative framework that empowers students to act on their benefit, in pursuit of their social interests and learning (agency). It should create a social climate where students can claim ownership over the class dynamics and, in their uniqueness, play an active role in the construction of the best version of themselves, as investment (Fairclough, 2011; García & Gil, 2007; Kress, 2011; Peirce, 1998; Lane et al., 2003; Norton, 2013; Song, 2016).