1. Introduction

The collaborative construction of knowledge is an alternative to engage students in their learning processes while constructing solid learning communities. Thus, teaching and learning have become actions intended to foster essential long-life skills which transcend schools and universities’ walls. In this sense, subject matters are called to be scenarios where different perspectives on the nature of current issues may be invoked and discussed. English classes should aim at nurturing communicative and thinking skills alike. In this regard, Chen (2016) declares that “when students’ thinking involves the extended exchange of various perspectives, which provides opportunities to engage in critical thinking such as analysing, providing reasoning for certain perspectives, categorizing, problemsolving, and commenting on other’ thoughts, optimal learning of thinking occurs” (p. 219). In other words, English classes should equip students with opportunities to foster communicative skills while rehearsing and strengthening Higher Order Thinking Skills (HOTS). Furthermore, when students are exposed to teaching and learning practices characterized by the scaffolding of analyzing, evaluating, and creating skills, they are prompted to reflect on their learning regarding the resulting benefits of activating specific thinking schemata and functions. The latter scenario corresponds to this paper’s case. During two years, legal English lessons at a private university in Colombia were oriented, bearing in mind Bloom’s taxonomy and HOTS. Lessons aimed at enhancing speaking skills in English as a Foreign Language (EFL) and additionally served to foster higher thinking.

Hand in hand with students, knowledge construction and skill training have become a suitable pedagogical path, an ideal teaching scenario, and a desirable learning goal. Regarding the latter, legal English courses at Universidad Santo Tomás (hereafter referred to as USTA) in Villavicencio (Colombia) are aimed at developing argumentation and communication skills in EFL. Ahmed (2014) asserts that English for Specific Purposes (ESP) “teaching is generally understood to be very largely concerned with external goals [...] External goals suggest an instrumental view of language learning and language being learned for non-linguistic goals” (p. 5). This research used English to lead students to engage in higher-order thinking while discussing current issues in which law plays a relevant role.

They could speak about daily stuff such as personal preferences, routines, past activities, etc. However, the needs analysis conducted as a prior requisite to design ESP courses rendered data about unelaborate performance concerning arguing ideas, supporting viewpoints, or analyzing current issues. Students were acquainted with legal subject matters while pursuing the law program; however, they needed help to express their ideas on legal issues in English effectively. Consequently, the researcher determined in terms of “necessities: what the learner should be able to do effectively in the target situation [...] Lacks: the gap between target proficiency and present performance and [...] Wants: what the learners want or feel they need” (Barrantes, 2009, p. 133). To meet students’ needs, the legal English course was designed bearing in mind the nature of ESP as “a social setting which is learner-centered, interactive, cumulative, goal-directed, diagnostic, reflective [where] both English language learning and higher order thinking skills [may be encouraged]” (Ashton-Hay, 2006; Tuzlukova & Usha-Prabhukanth, 2018, p. 44). Considering the previous statements, this study intended to provide an answer to the following question: what is the impact of fostering Higher Order Thinking Skills (HOTS) within legal English classes?

This article displays students’ insights regarding HOTS in legal English classes and its contributions to their academic life and future professional performance. It provides an account of previous research about the embedment of HOTS, language teaching, and learning within ESP settings. It also details the research methodology, data collection, analysis, findings, and conclusions.

2. Theoretical framework

This study’s foundational theoretical constructs comprise previous research on HOTS, critical thinking, and ESP.

2.1. Higher-order thinking skills

Thinking skills have been systematized in various taxonomies to show how knowledge develops and how to transition from basic skills to more complex ones. Taxonomies are helpful for teachers as they may serve as a guide to plan lessons, create assessment activities, design significant learning experiences, and follow up on students’ progress. For instance, Webb’s depth of knowledge framework (DOK) organizes higher-order thinking into four domains: recall, skills and concepts, strategic thinking, and extended thinking. Irvine (2021) states that Webb’s DOK focuses “on the use of knowledge […] and on the complexity of thinking” (p. 16). At the initial level, students are required to recall basic information, such as facts, definitions or procedures. As they move forward, they are expected to complete multiple steps and engage in complex reasoning.

Wiggins & McTighe (2005) refer to 6 facets of understanding as explanation, interpretation, application, perspective, empathy, and self-knowledge that do not only consider cognitive aspects of learning but also awareness of own and others’ boundaries regarding understanding or the ability and willingness to act on what is understood. Manzano & Kendall (2007) also provide a perspective on the processes involved in learning. Their model “posits three systems of thought that have a hierarchical relationship in terms of flow processing: the self-system, the metacognitive system, and the cognitive system” (p. 19); these three systems include “processes that address retrieval, comprehension, analysis, and knowledge utilization” (p. 63). Unlike Wiggins & McTighe’s taxonomy, Manzano & Kendall’s approach to thinking is still hierarchical and determined by the complexity of each process.

Dee Fink (2013) proposed a revision to Bloom’s taxonomy and suggested the conjunction of six aspects to foster significant learning as a way to respond to emerging areas such as “leadership and interpersonal skills, ethics, communication skills, character, tolerance, the ability to adapt to change, etc.” (p. 34), that cannot be easily handled from the cognitive domain of Bloom’s taxonomy. In response to the gap, Dee Fink (2013) designed “the taxonomy of significant learning that is not hierarchical but rather relational and even interactive […], and it means the various kinds of learning are synergistic” (p. 37). Thus, significant learning implied the convergence of six categories: foundational knowledge, application, human dimension, caring, learning how to learn and integration.

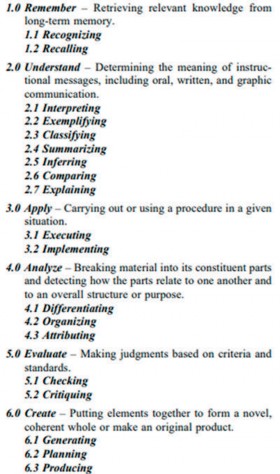

Previous taxonomies or frameworks are alternatives to Bloom’s taxonomy. According to Bloom et al. (1956), cognitive skills are categorized into Lower Order Thinking Skills (LOTS) and HOTS, as displayed in Figure 1. This study is consistent with the framework proposed by Bloom et al. (1956), as by mapping students’ insights into thinking skills, Bloom’s taxonomy provides a suitable approach to trace students’ understanding of the features and actions correlated to HOTS (analysis, evaluation, and creation).

This article displays students’ insights regarding HOTS in legal English classes and its contributions to their academic life and future professional performance. It provides an account of previous research about the embedment of HOTS, language teaching, and learning within ESP settings. It also details the research methodology, data collection, analysis, findings, and conclusions.

Note. Adapted from Krathwohl (2002, p. 215), A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy: An Overview.

Figure 1 Structure of the knowledge dimension of the revised taxonomy

The six categories of cognitive skills range from actions involving a minor degree of cognitive processing (LOTS) to those entailing a superior degree of cognitive processing (HOTS) (Adams, 2015). According to Krathwohl (2002), Bloom’s taxonomy “is a framework for classifying statements of what we expect or intend students to learn as a result of instruction” (p. 212). Individuals are taught to do a wide range of actions but should also receive instruction in thinking. Learning by doing allows teachers and students to explore, make discoveries and even pursue invention. Learning by thinking leads to analyzing, questioning, making changes, defending or contradicting assumptions, reading between the lines, and being skeptical and proactive, among others. In this regard, Chinedu et al. (2015) state that “HOTS should be an important aspect of the teaching and learning process because one of the major goals of teaching is to ensure that students can think and solve problems critically” (p. 37).

Likewise, Thomas & Thorne (2009) emphasize that lessons to develop HOTS should teach students to construct concepts, make inferences, explain abstract ideas, visualize, and draw conclusions. However, Johansson (2020) and Köksal & Ulum (2018) stress that EFL courses omit HOTS and tend to focus on LOTS. In the same line of thought, Nourdad et al. (2018) state that “language teachers should aim at increasing the level of thinking in their classes” (p. 236), and propose explicit instruction on HOTS and complex questions to prompt students to think in higher levels. Tyas & Naibaho (2021) suggest formulating problems as an alternative to foster HOTS-based learning. Thus, this study allowed students to familiarize themselves with HOTS and practice their skills. For this study, the researcher could trace students’ understanding of the features and actions correlated to HOTS (analysis, evaluation, and creation).

Successful implementation of a HOTS-based approach depends on aspects ranging from students’ perceptions towards English language learning to teachers’ training to design and execute HOTSbased lesson plans. In this sense, Azian et al. (2017) state that teachers must be equipped with the proper knowledge and skills to explain effectively and model HOTS strategies and, at the same time, are willing to provide students with ample opportunities to activate and utilize HOTS in the L2 classrooms. On the other hand, students should be challenged to become active learners who monitor and reflect on their learning processes while evaluating and interpreting information critically, which is associated with the view of the foreign language not as an end itself, but as a valuable tool to carry out actions and foster thinking (Ferrando, 2023).

Thus, the design and execution of HOTS-based lessons demonstrated promising results regarding communication, critical thinking, and lifelong learning skills; nonetheless, favorable outcomes also rely upon active commitment from teachers and students. In other words, on the teacher’s side, it requires knowledge and application of procedures to design and provide HOTS-based learning experiences and suitable strategies to evaluate and assess learning goals. As for students, the initial reflection on learning needs should also be hand in hand with self-regulation, autonomy, and the willingness to participate in each activity proposed.

In the Colombian educational context, various research studies have been conducted to foster HOTS in English classes (Cordoba & Cárdenas, 2016; Bautista & Parra, 2016; Esteban et al., 2018). Cordoba & Cárdenas (2016) conducted a research study with eleventh graders to assess the case method’s contribution to developing critical thinking skills. They concluded that the case method allowed students “to investigate, reflect, analyse, and discuss diverse topics” (p. 5), and “encourage high-order cognitive processes” (p. 6). Bautista & Parra (2016) explored “the practice of critical thinking as a strategy to appreciate art that expresses social issues” (p. 85). Thus, they conducted a research study with schoolers. They determined that “participants recognized critical thinking as a powerful instrument to find knowledge in the work of art, not just something on a canvas but as a human experience inside each one” (p. 99). Experiences, as previously mentioned, should become trendy in elementary and middle education schools in Colombia, as they may pave the way for educating higher thinkers in any professional field.

As for the higher education level, Esteban et al. (2018) conducted “a pedagogical implementation with pre-intermediate English students in an English teacher preparation program at a public university in Colombia” (p. 141) using workshops aimed at guiding students to “observe, analyze, reflect and discuss some political cartoons’’ (p. 141). Students developed a critical opinion and were able to reflect on real social problems while learning English.

2.2. HOTS and the development of reasoning skills

In this study, HOTS are comprehended as a plethora of reasoning skills that somehow rely on one another to be fostered, developed, and implemented successfully in daily life, such as critical thinking, problem-solving, creativity, inference, logical thinking, hypothesizing, among others. Accordingly, this study explored reasoning skills when analyzing real legal cases, penalties awarded, news, and legislative measures. Thus, HOTS are neither conceived as a block impossible to be fractioned and elucidated nor as a series of pieces that may be put together to frame the view of what students should learn and be skilled at. They are a valuable guide to understanding the human mind’s potential and inquiring on how, from different fields of studies-in my case, TEFL and ESP-teachers can contribute to achieving the highest human mind capacities.

In this sense, as a way to systematize findings, this study adheres to Brookhart’s (2010) and Tuzlukova & Usha-Prabhukanth’s (2018) understanding of HOTS. Brookhart (2010) classifies HOTS into three categories: HOTS in terms of transfer, HOTS in terms of critical thinking, and HOTS in terms of problem-solving. The transfer instructs students to think and apply knowledge and abilities in authentic contexts. Critical thinking “equips students to reason, reflect, and make sound decisions” (p. 6), and problem-solving guides students to “identify and solve problems in their academic work and life” (p. 8). In this research framework, students engaged in activities to apply knowledge in a real context (law and real legal cases). They were also involved in activities to reflect and figure out decisions or courses of action concerning legal issues addressed in class. Students eventually proposed solutions to real problems in which law plays a relevant role. Tuzlukova & Usha-Prabhukanth (2018) expand the idea of HOTS as critical thinking and assert that good critical thinkers tend to scrutinize ideas, query claims, detect, analyze and judge arguments, infer and present options, justify, draw conclusions, and state results. Hence, language is used to communicate ideas derived from higher thinking processes resulting in a flow of ideas that may lead to posing solutions to current issues, in other words, transferring knowledge and applying acquired skills.

Previously mentioned approaches to HOTS describe what students were expected to do in the legal English classes under a HOTS-based methodology. They were guided to follow the learning path framed by HOTS implicitly. In this regard, English learning comprises transfer, critical thinking, and problem-solving (Brookhart, 2010). In Colombia, the area of Teaching English as a Foreign Language (TEFL) has also been influenced by the view of English classes as scenarios to foster thinking. Based on their research studies, Pineda (2004), Fuquen & Jiménez (2013), Fandiño (2013), and Sandoval & Anturi (2020) have concluded that EFL classes pervaded by critical thinking favor the development of criticality, metacognition, reflection, creativity, and collaboration.

2.2. English for specific purposes (ESP)

ESP emerged in the 1960s as a mode of teaching English to meet learners’ specific needs. Initially, learners’ needs corresponded to the lexicon applied in particular contexts (Halliday et al., 1964). Afterward, learners’ needs were conceived as the aims, skills, discourse, and appropriate genres (Dudley-Evans & St.John, 1998) and the language used in determined contexts (Belcher, 2006). Thus, a transition from an isolated lexicon to interaction in specific contexts emerged.

Vanicheva et al. (2015) define ESP as “a training operation which seeks to provide learners with a restricted competence to enable them to cope with certain clearly defined tasks” (p. 661). In this case, the ESP course served a twofold objective. First, fostering communication skills in EFL (speaking about legal issues, arguing, expressing opinions, questioning ideas, and justifying one’s stance, among others); second, strengthening HOTS (analyzing, evaluating, creating, metacognition, self-regulation, and autonomy). Yu & Xiao (2013) emphasize that legal English courses should enable students “to become active in thinking and broad in vision” (p. 1125). Thus, their scope necessarily surpasses mere subject knowledge and language proficiency. Learners should be guided to purposefully apply knowledge in real settings and explode language as a hint of thinking. In Colombia, Arias Rodríguez & Roberto Flórez (2021) allude to cognitive competence as a learning goal in legal English courses. It involves interpreting, arguing, and proposing.

For example, they [learners] need to understand problematic situations, investigate information related to the case, identify the processes, recognize the different parts of the cases, and argue the possible solutions based on the latest legal regulation, jurisprudence, and the appropriate context. (p. 11)

In this manner, Arias Rodríguez & Roberto Flórez (2021) describe the learning path of students enrolled in legal English classes oriented under the HOTS-based approach. They refer to professional communication in the field of law as it is the main goal of ESP courses. In this regard, Le (2021) draws attention to the necessity to favor “language knowledge, but also contextual knowledge [...] strategic communicative competence, pragmatic competence, or pragmalinguistic and sociopragmatic skills” (n. p.). In the present research study, students had the opportunity to delve into contextual issues (environmental detriment, cybercrimes, human rights, etc.) to foster their professional skills.

3. Methodology

The present study corresponds to a descriptive longitudinal mixed methods approach research. Longitudinal studies are conducted to evaluate a variable or variables over some time. Caruana et al. (2015) state that “longitudinal studies employ continuous or repeated measures to follow particular individuals over prolonged periods” (p. 537). In this case, the period covered two years (four semesters) that started in the second academic term of 2018 and concluded in the first academic term of 2020. It comprised four semesters, and each semester was around 17 weeks long. Two concurrent courses of legal English took part in the research. Students took a 2-hour legal English class a week. According to Cohen et al. (2007), “descriptive research studies look at individuals, groups, institutions, methods, and materials in order to describe, compare, contrast, classify, analyze and interpret the entities and the events that constitute their various fields of inquiry” (p. 205). Data collected were analyzed by implementing Grounded Theory, a constant comparative method developed by Glaser & Strauss (1967). Participants were asked to provide their insights into the methodology used in the legal English classes they were enrolled in. Thus, the present research study aimed at mapping HOTS in legal English classes at a private university in Colombia and analyzing students’ insights regarding legal English classes conducted under a HOTS-based approach.

3.1. Setting

This research took place at USTA, a private, catholic, and accredited university in Villavicencio, Meta, Colombia. Its pedagogical model promotes students’ integral development and growth in being, doing, and acting (Universidad Santo Tomás, 2010). Thomas Aquinas’ Christian humanism inspires it, and in this sense, it is devoted to intellectual work, rigorous and profound knowledge, open dialogue, philosophical debate, science, and the search for wisdom, as is stated in its motto: facientes veritatem (Universidad Santo Tomás, 2010).

In line with the pedagogical model, students are expected to develop critical skills such as observing and analyzing the surrounding reality to judge it and take action. As a General Studies University, USTA intends to articulate universal knowledge to attain a general view of the world and humankind, the multiple relationships with reality, and the diverse manners of interpreting and tackling transformation (Universidad Santo Tomás, 2010). Concerning English teaching and learning, language policies are determined by an agreement (Universidad Santo Tomás, 2014) which provides the general guidelines to design, execute and evaluate English courses at USTA. The Superior University Council enforced the agreement as part of the update of foreign language teaching and learning policies, which intended to standardize curricular and assessment procedures at the university branches nationwide. As a result, undergraduate students should achieve a B1 proficiency level according to the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR) as a requirement for graduation.

3.2. Participants

This study counted on the participation of 56 law students enrolled in the legal English courses at USTA in Villavicencio, Colombia. In 2018, they became involved in some lessons designed as an introduction to legal English courses. After a year of participating in English lessons where legal issues were discussed, in 2019, they started their legal English classes. At USTA, law students are expected to pursue two legal English courses on a 2-hour weekly basis each. The researcher requested students’ consent to collect research data (see Appendix D). As previously mentioned, students at USTA Villavicencio are expected to achieve a B.1.2 proficiency level in English. Thus, in order to enroll in the legal English 2 courses at the time this research was conducted, they had to approve 7 levels of general English (levels A1 and A2) and the legal English 1 course (B1).

For this research, two classes (legal English 2A and legal English 2B) were selected. The number of students varied in each course because they chose the most convenient timetable, as the courses were offered at different hours and days; however, the content was the same for both groups. (Table 1)

3.3. Data collection instruments

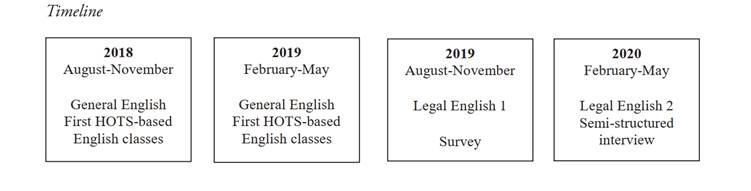

Three instruments were designed and used to collect data that contributed to determining the impact of fostering HOTS in legal English classes: a survey, a semi-structured interview, and the students’ artifacts. The data collected only accounts for the participants’ perceptions at the final stage of implementation of the HOTS-based methodology. The following timeline accounts for the pedagogical intervention and the data collection stages. (Figure 2)

The survey and the semi-structured interviews were assessed by expert colleagues in order to add validity. The table below shows the profile of the expert colleagues in terms of their education and experience in English Language Teaching (ELT), ESP and HOTS. (Table 2)

Table 2 Expert colleagues’ profile

| Expert | Education | Teaching Experience | ResearchInterest | ESPExperience |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expert A | B.A. in Languages M.A. in Language TeachingPh.D. candidate in Education | He has worked in teacher training programs in higher education for 13 years | Growth mindset Personal narratives Metacognition Hermeneutics Assessment | He has been in charge of ESP courses (Legal English) |

| Expert B | B.A. in Foreign Languages -English, Spanish and French Diploma in TESOL M.A. in English Language Teaching for Self-directed Learning | He has worked as an English and French teacher at different educational levels | CLILEFLClassroom managementSelf-directed learning and autonomy Standardized tests SMART goal-setting |

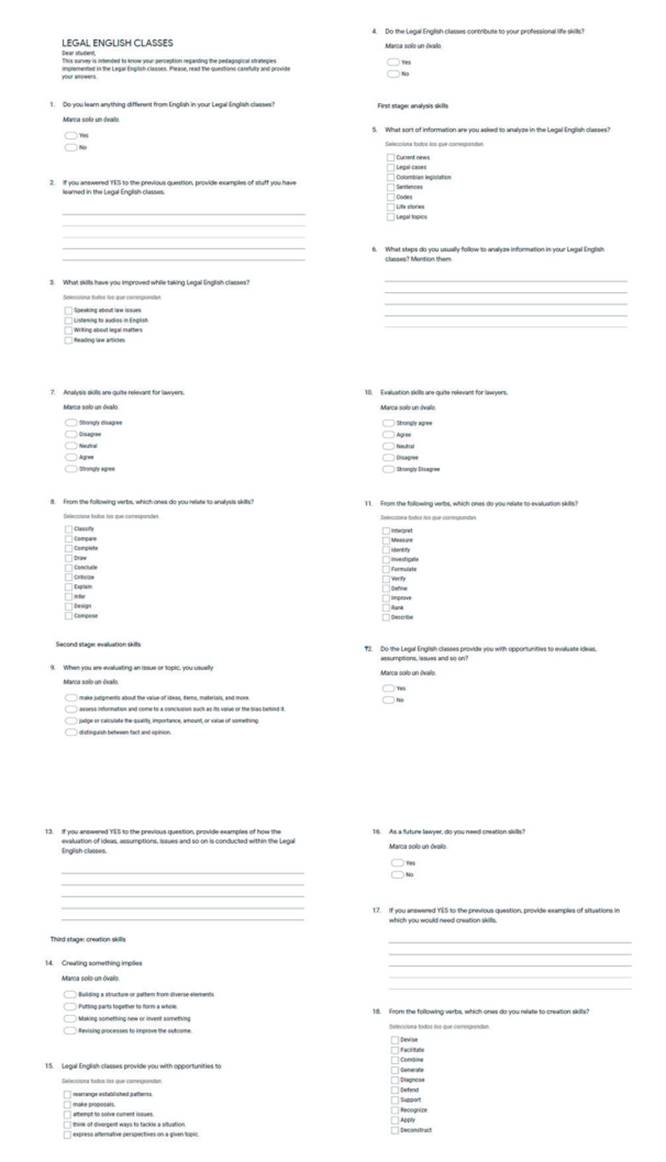

3.3.1. Survey

In 2019 a survey was conducted to collect data concerning students’ assumptions and insights about the legal English classes. In this stage, they finished the legal English I course; thus, they responded to questions about the course’s contribution to their professional life skills and learning beyond communicative competence in English. Furthermore, as they had been exposed to a HOTS-based English teaching methodology for a year and a half, they were consulted on issues such as the sort of analysis, evaluation, and creation activities conducted in class, actions correlated to analysis, evaluation or creation processes, and their conceptions and misconceptions about HOTS (see Appendix B). Cohen et al. (2007) assert that “typically, surveys gather data at a particular point in time to describe the nature of existing conditions, or identifying standards against which existing conditions can be compared, or determining the relationships that exist between specific events” (p. 205). The survey provided descriptive and explanatory information to ascertain correlations between HOTS, English language learning, and students’ future professional life skills.

3.3.2. Semi-structured interview

This data collection instrument is utilized in qualitative research studies and consists of predetermined, open-ended questions (Ayres, 2008). Thus, at the end of the study, a semi-structured interview was conducted to collect students’ comments on the methodology implemented, the resources, the evaluation strategies, and the activities done in the legal English classes. Additionally, the interview was a source of relevant data concerning legal English classes’ contributions to the student’s development as human beings, citizens, and future lawyers (see Appendix C).

3.3.3. Students’ artifacts

They intend to provide material evidence of the past through diverse information, historical, demographic, cultural, societal, and so forth (Norum, 2008). Thus, students’ artifacts may render valid data about their values, beliefs, ideas, assumptions, knowledge, and opinions. In the present study, artifacts were researcher-generated. In other words, the researcher asked students to express their ideas using Powerpoint presentations, which subsequently became study artifacts. Presentations were usually designed to display the outcomes of their collaborative work during the creation stage (see Figure 15 and Appendix E). (Figure 3)

3.3.4. Pedagogical intervention

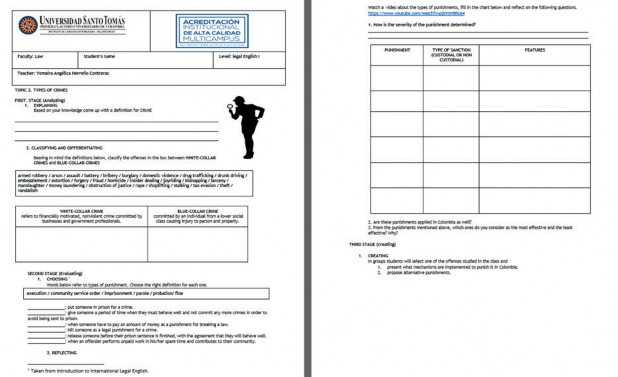

As English classes intended to foster HOTS and communicative skills in English, lessons were usually based on the following pedagogical cycle.

Legal English classes consisted of activities that adhered to Bloom’s taxonomy. In this sense, students initially engaged in activities to develop analysis. They were expected to interpret, compare, contrast, and establish relationships among various assumptions, hypotheses, or evidence. Afterward, they developed activities related to evaluation. In this stage, they were prompted to conclude, defend their ideas, and judge others’ assumptions based on specific standards and criteria. During the third stage, they were involved in activities concerning creation. The legal English class became a suitable creation scenario. In this regard, students were expected to develop something new related to the class topics. They hypothesized alternative views on determined legal cases, developed arguments to present their stand on the legal issues treated in class, revised jurisprudence, formulated ideas, and so forth. Table 3 displays the pedagogical strategies implemented during the legal English classes.

Table 3 Pedagogical strategies

| HOTS | STRATEGIES |

| Analyzing | → Group discussion → Opinionating → Word mapping → Scanning and skimming → Making definitions → Gap filling → Brainstorming→ Teacher’s questioning (convergent, divergent, procedural) |

| Evaluating | → Video watching → Critical listening → Opinionating → Film watching → Matching→ Listening comprehension→ Teacher’s questioning (convergent, divergent, procedural) |

| Creating | → Collaborative work → Debates→ Oral reports → Creation of legal cases → Oral presentations→ Teacher’s questioning (convergent, divergent, procedural) |

4. Data analysis

Data analysis was done by applying Grounded Theory. Glaser & Holton (2004) state, “the conceptualization of data through coding is the foundation of GT development. Incidents articulated in the data are analyzed and coded, using the constant comparative method, to generate initially substantive, and later theoretical, categories” (p. 12). Google Forms questionnaires were used to create and conduct the survey and the semi-structured interview in order to collect students’ insights about the legal English classes. Thus, once the data collection instruments were on Google Forms, a link was sent to the students via e-mail. First, they responded to the survey questions after having been exposed to HOTS-based English classes for one year and a half (2 courses of General English and 1 course of legal English), as this methodology was initially introduced when they were enrolled in General English classes. The semi-structured interview was conducted at the end of the Legal English II course. Google Forms allows the creation of an Excel spreadsheet comprising the whole data collected that was subsequently fractured and grouped into codes which led to emerging categories and subcategories. In this regard, Charmaz (2006) asserts that “coding means that we attach labels to segments of data that depict what each segment is about” (p. 3). Firstly, open coding was conducted, and pieces of data were broken down, examined, compared, and categorized. Afterward, axial coding provided a clearer view of how categories and subcategories were correlated. Regarding the quantitative analysis of the data collected, the Excel Workbook Statistics was used to obtain the percentages and correlations included in exploring each category and subcategory.

5. Findings and discussion

Two categories and six subcategories emerged from the research question and the data analysis. They are presented and described as follows (Table 4):

Table 4 Emerging categories and subcategories

| Research question | First categoryPerceived impacts on students’ learning | Second categoryStudents’ views concerning HOTS |

| What is the impact of fostering Higher Order Thinking Skills (HOTS) in legal English classes? | Subcategory 1. Learning to communicate in English Subcategory 2. Learning to think higherSubcategory 3. Learning for future professional life and citizenship | Subcategory 1. Becoming involved in analyzingSubcategory 2. Becoming involved in evaluatingSubcategory 3. Becoming involved in creating |

5.1. First category: perceived impacts on students’ learning

This study served a threefold purpose: firstly, to identify students’ perceptions concerning legal English classes after two years of being involved in HOTS-based English lessons; secondly, to determine the impact of instruction mediated by HOTS on students’ English learning, and thirdly, to pinpoint and analyze strengths and weaknesses of the methodology implemented.

Thus, as part of the legal English lessons, students engaged in activities intended to awaken and strengthen HOTS while tuning communicative skills to argue, set viewpoints, justify, and debate current issues (environmental detriment, cybercrimes, human rights, etc.), among others. Consequently, legal English classes became learning scenarios oriented to communicating in English, thinking higher, and growing awareness of one’s commitment as a citizen and future professional. In this regard, the present study correlates with the one conducted by Chen (2017) in the sense of generating “a wide impact on students’ learning, ranging from immediate effects on student learning to a wider impact on long-term learning” (p. 516). In the legal English classes, students applied their background legal knowledge and developed critical skills for their future professional life, such as analyzing, evaluating, and creating.

Furthermore, students gave their opinion about the strengths and weaknesses of the methodology implemented: “the classes were participative and intended to foster opinion and interaction” (Student 14, Interview, 29.05.2020). Similarly, another student asserted that the English classes’ methodology was “super good as it was characterized by analyzing students’ potentials and attempting to exploit them to make students improve their English level” (Student 3, Interview, 29.05.2020). Students valued the legal English class methodology and pondered the benefits of using their background legal knowledge while ameliorating their HOTS.

5.1.1. Subcategory 1: learning to communicate in English

Over two years, participants engaged in legal English classes focused on the in-tandem development of HOTS and communicative skills in EFL. In other words, legal English classes intended to provide students with opportunities to improve their English level but also were designed to nurture their higher thinking. As a result, they reflected on their speaking, vocabulary gain, and reading progress. Concerning speaking skills, one student declared, “all the class activities were intended to make students speak. Thus, we had to look words up and get acquainted with their proper usage” (Student 2, Interview, 29.05.2020). Another student stated that “in-class presentations contributed to overcoming nervousness while speaking because I did not know how to handle presentations in English, and in this semester’s English classes, I did not feel pressured to speak” (Student 23, Interview, 30.05.2020). Thus, English classes assisted students in coping with their fears and weaknesses.

Regarding reading and vocabulary, one student declared that he attained reading texts in English and improved his vocabulary. Then, reading became easier for him (Student 3, Interview, 29.05.2020). These findings correlate with Chen’s study results, as her research demonstrated a connection between improving communicative skills and implementing the HOTS approach in English classes. According to the author, “higher-order thinking provides L2 learners with more language learning opportunities, leading to better student learning” (Chen, 2017, p. 518). Thus, HOTS is a meaningful tool to guide students to a better learning process. As shown in Figure 4, 19 students (68 %) considered that they improved their speaking and writing, whereas 6 students (21 %) deemed their comprehension skills outstanding. Students mostly acknowledged that they improved their speaking skills. One student declared that English classes “provided him with new knowledge, public speaking, and teamwork skills” (Student 21, Interview, 29.05.2020).

5.1.2. Subcategory 2: learning to think higher

Classes were designed to foster HOTS as well (see Appendix A). Thus, after two years of implementing a HOTS-based approach for legal English classes, it was required to delve into to what extent students were aware of the development of higher thinking. One student pondered the relevance of the activities done in class as “they were the starting point to develop and strengthen HOTS” (Student 14, Interview, 29.05.2020). Similarly, another student highlighted that the class activities assisted them in learning and forging his criteria in order to provide arguments on a given issue (Student 20, Interview, 29.05.2020). It took much work for students to deal with an ESP course (legal English) that fosters communicative skills in a foreign language and higher thinking. It made legal English lessons challenging for students. In this regard, Roell (2019) states that “the more complex the case is, the more specific the knowledge and the more specialized the language students will need” (p. 25). The challenge for students consisted of coping with speaking skills and communicating their insights based on analyzing and evaluating a given issue. One student said, “analyzing, evaluating, and creating in a foreign language was difficult. It had been more accessible in my mother tongue; however, doing so in a foreign language allowed me to learn new concepts and aspects to become more analytical when speaking and evaluating cases, facts, and circumstances” (Student 24, Interview, 01.06. 2020). It is relevant to diagram what students could do regarding higher thinking.

In terms of analyzing, students referred to the steps they usually followed to analyze information in legal English classes: “Investigate, analyze, compare and argue” (Student 6, Survey, 05.10.2019). Another student provided a more detailed description of the analysis process: “I look for cases in reliable sources, study the facts, read how the judge gave a solution to the case and his decision” (Student 11, Survey, 06.10.2019). Furthermore, another student deemed analysis a pivotal step in developing his speech and ideas: “I usually need to analyze information by researching the topic I want to learn. After this, I focus specifically on what I will talk about, and finally, I sort and classify the information obtained to develop it in my speech” (Student 24, Survey, 07.10.2019). The previous students’ assertions account for three perspectives on analysis skills, their uses, and their scope. (Table 5)

Table 5 Students’ abilities in the light of higher thinking based on Bloom’s action verbs

| ANALYZING | EVALUATING | CREATING |

|---|---|---|

| Students distinguish, classify, and relate a statement or question’s assumptions, hypotheses, evidence, or structure. | Students appraise, assess, or critique based on specific standards and criteria. | Students originate, integrate, and combine ideas into a product, plan, or proposal that is new to them. |

| Analyze, compare, contrast, infer, explain, discriminate, differentiate, prioritize, break down, discover, illustrate, interpret, demonstrate, separate, categorize. | criticize, reframe, order, appraise, assess, estimate, find errors, measure, predict, choose, value, rate, justify, judge, defend, support, conclude. | design, compose, create, hypothesize, develop, modify, rewrite, prepare, synthesize, revise, reconstruct, rearrange, compose, combine, assemble, invent. |

Concerning evaluating, students provided examples of how the evaluation of ideas, assumptions, and issues was conducted in the legal English classes: “we read the case or situation, then we propose possible solutions, and discuss them in class, and finally, we obtain an answer” (Student 32, Survey, 08.10.2019). Another student stated, “the teacher asks questions about the topic, whether we agree or disagree on the issue, and then we start defending or counterarguing ideas” (Student 54, Survey, 24.10.2019). The primary purpose of leading students to analyze current issues was to make them correlate facts with the law and guide them to provide sound arguments and answers.

Regarding creating, students also provided examples of how this sort of skill was fostered in the legal English classes: “create good arguments” (Student 29, Survey, 07.10.2019), and “create alternatives to solve cases” (Student 37, Survey, 15.10.2019). Another student provided a detailed description of an in-class activity developed to foster creation skills: “when the teacher talks about a topic, she always asks us about the definition, opinion, classification, and everything about the topics. Then, there is a debate among students about issues related to definitions and examples, and this is a good exercise because sometimes they are wrong, and we all learn” (Student 43, Survey, 24.10.2019).

5.1.3. Subcategory 3: learning for future professional life and citizenship

As legal English classes were embedded within an ESP course, students were prompted to reflect on how English lessons contributed to their roles as future lawyers and citizens. Students referred to the impact of the legal English class on their development as human beings, citizens, and future professionals. 28 students interviewed (100 %) acknowledged the positive impact of legal English classes. (Figure 5)

In this sense, students shared their insights, from improving oral expression and public speaking to personal growth. One student stated that classes engaged him in “observing the surrounding social reality from a critical perspective and assuming the challenge to speak about it in English” (Student 4, Interview, 29.05.2020). Similarly, another student highlighted his learning in terms of “knowledge to be applied in his professional and personal life, expressing ideas and understanding speech acts in English” (Student 22, Interview, 29.05.2020). According to Porto & Byram (2015), citizenship education should respond to three primary purposes: “social and moral responsibility, community involvement, and political literacy” (p. 21). In the present research framework, students were exposed to the HOTS-based approach. They had the opportunity to develop responsible behavior (social and moral responsibility) toward current issues such as cybercrimes, environmental detriment, dispute resolution, miscarriages of justice, and workers’ rights. Thus, they did not limit themselves to just providing an opinion on a given issue; in contrast, they took a position. In other words, they learned how to become involved in their social reality, not just as mere spectators, but as active citizens who wanted “to make themselves effective in the life” (p. 21) of their locality, region, nation, and beyond (community involvement and political literacy).

Concerning the legal English classes’ influence on aspects differing from communicative competence, students valued some areas of personal development referred to as “being integral professionals” (Student 8, Interview, 29.05.2020), “personal growth” (Student 10, Interview,29.05.2020), “being active and participative” (Student 14, Interview, 29.05.2020), “thinking about pursuing a master degree abroad” (Student 23, Interview, 30.05.2020), “professionally speaking, English classes helped me to be motivated to learn a foreign language, and personally speaking, I learned to be patient, persistent and never give up regardless of the difficulties” (Student 25, Interview, 01.06.2020). These students’ reflections correlate to the USTA pedagogical model that enshrines the students’ integral development and growth in being, doing, and acting.

5.2. Second category: students’ views concerning HOTS

Based on a two-year implementation of a HOTS-based approach in legal English classes, the present article intends to display students’ views on HOTS in legal English classes and its contributions to their current academic life and future professional performance. One student states, “HOTS were developed because the class activities were oriented to foster this sort of skills” (Student 14, Interview, 29.05.2020). According to Othman & Mohammed (2014) and Salem (2018), innovative teaching and learning strategies significantly contribute to developing HOTS. On the one hand, Othman & Mohammed (2014) refer to Malaysia Smart Schools that focus on “intellectual, emotional, spiritual and physical growth, concentrating on thinking, developing and applying values” (p. 30). On the other hand, Salem (2018) highlights the significant gains in functional writing skills in flipped HOTS-based classrooms. In this sense, the present research correlates to Salem’s findings. He applied an innovative methodology guided by flipped learning in a Business English course. In contrast, the present study comprised a HOTS-based approach that allowed students to learn legal English in a divergent manner. Both studies demonstrated that the application of alternative methodologies resulted in the improvement of HOTS in ESP courses.

5.2.1. Subcategory 1: becoming involved in analyzing

According to Bloom et al. (1956), cognitive skills are categorized into LOTS and HOTS. Thus, after strengthening skills (such as remembering, understanding, and applying), students are expected to engage in analyzing, evaluating, and creating. This study’s focus was on HOTS. In their professional life, lawyers need to apply HOTS masterfully. In this regard, James (2012) states that law graduates should be able to “identify and articulate legal issues, apply legal reasoning, engage in critical analysis and think creatively in approaching legal issues and generating appropriate responses” (p. 68). To contribute to the lawyer’s professional profile, students participated in activities intended to foster analysis, evaluation, and creation (see Pedagogical Intervention section). Concerning the analysis activities, one student declared, “I usually need a good search on the topic I want to learn to analyze information. Afterward, I focus specifically on what I am going to talk about. Moreover, I sort and classify the information obtained to develop it in my speech” (Student 24, Survey, 07.10.2019). Another student referred to analyzing the information as follows: “read the case, read about related topics, and try to solve it with the law codes” (Student 34, Survey, 08.10.2019).

Based on the previous assertions, it is necessary to have an object to start the analysis process-for instance, the legal case and the extra information about it. Afterward, the collected data is usually classified and categorized, even fragmented into smaller chunks, to understand the issue better and build a foundational ground to discuss it. Analyzing an issue, an object, an event, etc., comprises a series of actions. As it was previously mentioned, participants in this research attended legal English classes oriented under a HOTS-based approach for 2 years. To determine the impact of fostering HOTS in legal English classes, they were surveyed to know to what extent they were aware of actions and in-class activities related to HOTS. In this sense, Figure 6 displays the correlations made by students in this regard.

The statistics displayed in Figure 6 arose from a questionnaire (see Appendix B) students answered when concluding the first year of pedagogical intervention. Some key verbs related to analysis skills are calculate, contrast, categorize, discriminate, examine, infer, model, and test. When students were asked to correlate some verbs to the analysis skills, 66,1 % (37 students) associated them with making comparisons, 44,6 % (25 students) with classifying, and 46,4 % (26 students) with making inferences. However, actions such as concluding (51,8 %), criticizing (60,7 %), and explaining (50%), essentially related to evaluation skills, were also equated to analysis skills.

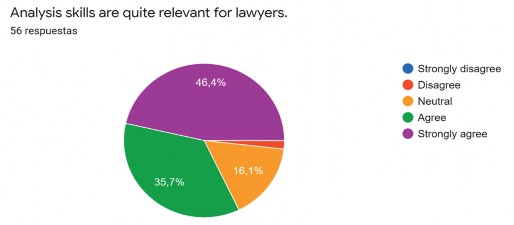

Regarding the relevance of analysis skills for lawyers’ professional life (see Figure 7), 46,4 % (26 students) strongly agreed that this sort of skill is required to perform professionally, whereas 35.7 % (20 students) agreed on the analysis skills to be vital in their professional life. Only 16,1% (9 students) did not express any idea on this assumption, and 1 student (1,18 %) disagreed with considering this skill part of lawyers’ professional tasks. In this sense, Kift et al. (2010) state that “law graduates should be able to examine a text and/or a scenario [...] find the key issues, and articulate those issues clearly as a necessary precursor to analysing and generating appropriate responses to issues” (p. 17). Some examples of texts and scenarios are legal documents, legal narratives, statutes, case reports, or facts. The research study’s students analyzed real legal cases, penalties awarded, news, and legislative measures.

5.2.2. Subcategory 2: becoming involved in evaluating

Students were involved in various activities that required them to evaluate diverse data types (assumptions, cases, proceedings, verdicts, and pieces of news). Figure 8 displays students’ insights concerning evaluation skills.

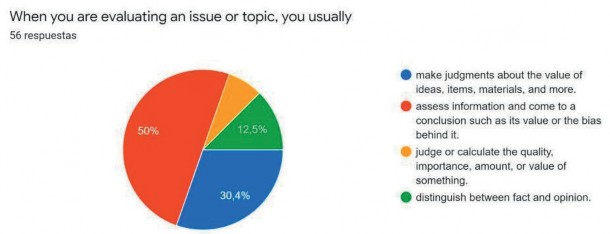

The four definitions provided for evaluation portray vital features that contribute to having a general picture of evaluating as a thinking skill. 28 students (50 %) associated evaluation with assessing information and coming to a conclusion, such as its value or the bias behind it. In their law classes, they were familiar with examining legal cases in detail to provide legal advice or the best course of action. Thus, that is why most of them first related evaluation to assessing, drawing conclusions, and even determining bias and value. 17 students (30,4 %) considered that evaluation consisted of making judgments about the value of ideas, items, materials, and more. This assumption reveals that valuable information is crucial to a lawyer’s professional performance.

Consequently, students tended to discard irrelevant information that provided no hint or ground to solve a legal case. In this regard, Silver et al. (2012) highlight the relevance of inference strategies to guide students in developing evaluation skills. In the present research study, the teacher presented “students with a puzzling question, a discrepant event, incomplete data, or an interesting problem to solve” (p. 6), legal cases, news, legal documents, among others. Based on the input, students were “expected to use their powers of reasoning to develop hypotheses and then test and refine them” (p. 6).

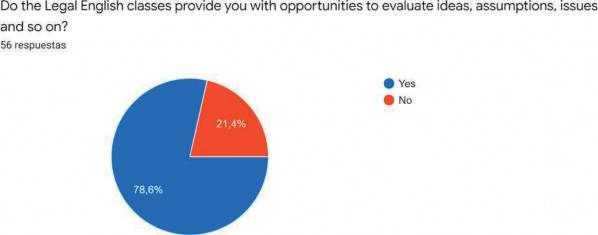

As part of their professional performance, lawyers should distinguish between facts and opinions, which is useful when applying legal reasoning. Legal reasoning involves examining facts, identifying the legal issues, and “identifying legal rules and processes of relevance to reach a reasonable conclusion or to generate an appropriate response to the issue” (Kift et al., 2010, p.18). 7 students (12,5 %) correlated evaluation with distinguishing, and 4 students (7,1 %) expressed that evaluation implied judging or calculating the quality, importance, amount, or value. Furthermore, when asked whether they had opportunities to evaluate issues, assumptions, ideas, etc., in the legal English classes, 44 students (78,6 %) responded affirmatively (see Figure 9).

In this regard, one student stated that “we can read about a case and distinguish between the facts and the measures taken, and whether this should be so or not according to our opinion. To do so, we took into account the current legislation and jurisprudence” (Student 24, Survey, 07.10.2019). Other students declared that the opportunities to evaluate ideas were related to “check real-life cases and their juridic components in order to talk about them” (Student 50, Survey, 24.10.2019), “study articles, current problems and make constructive criticism of the government” (Student 38, Survey, 18.10.2019). For other students, the evaluation also involved “proposing solutions, discussing the case in class and finally getting an answer” (Student 32, Survey, 08.10.2019), or “identifying offenses, checking sanctions or penalties in the codes, and even consulting experts” (Student 23, Survey, 07.10.2019). Consequently, previous students’ assertions demonstrate that they had some notions about evaluation skills and how to apply them in the English class.

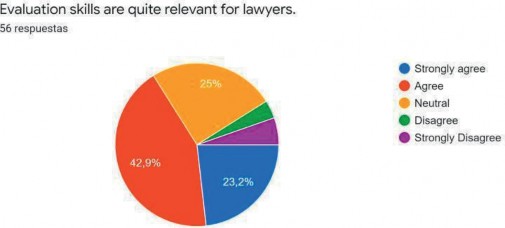

Nonetheless, the research also intended to delve into students’ perceptions of the usefulness of this sort of skill for their future professional performance. In this regard, 24 students (42,9 %) considered that lawyers must know how to evaluate facts, sources, and all the information related to legal cases. Thirteen students (23,2 %) strongly agreed on the usefulness of evaluation skills for lawyers. Surprisingly, 14 students (25 %) did not express any assumption on the utility of evaluation skills to perform as a lawyer. In contrast, 3 students (5,4 %) strongly disagreed, and 2 (3,6 %) disagreed with this idea. (Figure 10)

One student stated that evaluation skills are vital because they allow students to “give our point of view and substantiate it because we all have different solutions” (Student 34, Survey, 08.10.2019). For students, sharing their ideas and insights on a given case was relevant to know divergent viewpoints, defend their perspectives, and learn from their classmates. Furthermore, they were able to go beyond opinions and assess different views on a case in order to provide possible solutions. Thus, evaluation was a crucial step in solving a case. In this respect, one student declared that an opportunity to develop evaluation skills within the class was “looking for cases of greater incidence nationwide, identifying the problem and how to solve it” (Student 11, Survey, 06.10.2019).

To know students’ perceptions of evaluation skills, they were requested to correlate some verbs with evaluative thinking processes. According to Bloom et al. (1956), this thinking process concerns actions such as judging, interpreting, rating, measuring, summarizing, validating, explaining, and contrasting, among others. The figure below displays what students understood by evaluation skills. (Figure 11)

71,4 % (40 students) associated evaluation skills with interpreting, 55,4 % (31 students) with investigating, 41,1 % (23 students) with verifying and describing, and 37,5 % (21 students) with formulating and defining. They needed to gather data to understand a given case better and formulate their ideas. Although formulating is a creative thinking process, 21 students (37,5 %) viewed it as part of evaluation skills. Furthermore, some actions commonly associated with evaluation processes were not highly voted by students: measure (5 students, 8,9 %) and rank (5 students, 8,9 %). In this sense, students were never explicitly introduced to HOTS and their composition. However, in every class, they were immersed in lessons fully designed, considering the progression from analyzing to creating. Thus, their responses displayed how they understood each thinking skill based on their experience in class.

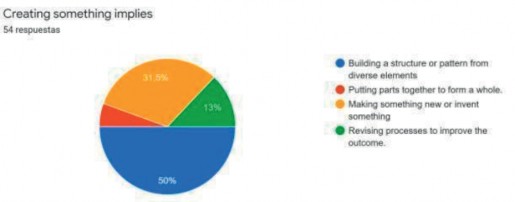

5.2.3. Subcategory 3. Becoming involved in creating

Concerning creation skills, 27 students (50 %) associated creation with building a structure from diverse patterns, while 17 students (31,5 %) identified creation as making something new or inventing something. Consequently, it may be inferred that students correlated creation with innovation. Thus, actions such as putting parts together to form a whole or revising processes to improve the outcome were less rated, corresponding to 5,6 % (3 students) and 13 % (7 students). Furthermore, the lessons’ design was intended to make them construct ideas, develop their arguments on given issues and counterargue if required. They never participated in activities such as assembling parts, which may explain why they needed to correlate revising processes and combining parts with creation skills. (Figure 12)

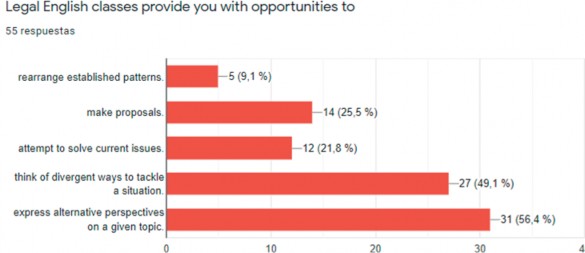

Students were exposed to various activities to foster creation skills during the legal English classes. As a result, 56,4 % (31 students) perceived that they could express alternative perspectives on a given topic, as most of the classes revolved around discussing current issues and attempting to provide divergent views. Thus, 49,1 % (27 students) considered they were prompted to think of divergent ways to tackle a situation. The legal English classes were designed to allow students to speak their minds; they usually contrasted legal issues, procedures, and their perspectives. One student stated that legal English classes were structured as follows: “study a case, identify the misconduct, verify the penalty or punishment in the corresponding code, consult experts on the issue, and apply what previously described in real life” (Student 23, Survey, 07.10.2019). Legal English classes usually revolved around cases students should analyze and evaluate to develop their arguments and ideas. At the end of the pedagogical cycle (Stage 3: creating), they usually participated in speaking activities such as oral presentations, round tables, and debates in which they should practice what they had learned over the process of delving into the specific case and gathering data to justify their posture.

To see to what extent in-class activities correlated with creation skills, students were asked to determine their creation activities in legal English classes. Based on Bloom’s taxonomy (Bloom et al., 1956), this thinking process concerns modifying, collaborating, designing, developing, and inventing, among others. The figure below displays what activities students considered as scenarios to develop creation skills in the legal English classes.

According to the information displayed in Figure 13, a lesser percentage of students remarked that legal English classes were scenarios to make proposals (25,5 %, 14 students), attempt to solve current issues (21,8 %, 12 students), or rearrange established patterns (9,1 %, 5 students). Students’ insights are displayed in the figure below regarding the usefulness of creation skills within the professional law field.

78,3 % (43 students) viewed creation skills as relevant to become competent lawyers. In comparison, 21,8 % (12 students) said they did not need them in their professional field. One student stated that “creation skills are needed in the formulation of new spaces for legal discussion since there are many lawyers who are not well prepared to exert the profession” (Student 24, Survey, 07.10.2019). Similarly, another student asserted that “creation skills are necessary, for example, to create a legal defense strategy or to prepare witnesses for a judicial process” (Student 33, Survey, 08.10.2019). Another student mentioned, “many social problems need a root solution and creation of effective norms” (Student 3, survey, 09.10.2019). Thus, students correlated creation skills with a lawyer’s actions: setting a defense strategy, preparing witnesses, contributing to solving social problems, and proposing new laws, among others. As students were constantly encouraged to participate in activities related to real law scenarios, they could determine the relevance of HOTS in their real-life professional duties. They could perceive their usefulness in their field of studies and their English learning process. Thus, legal English classes allow students to look at the surrounding context and dare to impact it from their field of studies. (Figure 14)

63 % (34 students) associated creation skills with defending, and 57,4 % (31 students) with generating, which makes much sense considering that they were law students; thus, preparing a defense or advocating for a cause implies putting into practice a wide range of creation skills to successfully resolve an issue, propose alternatives or win a case in the court. In this sense, one student stated that creation skills are required “when defending a person in a public hearing” (Student 21, Survey, 07.10.2019). Furthermore, other actions related to creation skills were voted on a smaller scale: devise (24,1 %, 13 students), facilitate (31,5 %, 17 students), and combine (38,9 %, 21 students). Concerning facilitating life in society, one student highlighted that creation skills are necessary “when there is a new social reality, [thus], laws are necessary to regulate this behavior” (Student 7, Survey, 05.10.2019). (Figure 15)

As an example of how students could put HOTS into practice within the legal English classes, the figure below displays the analysis conducted by some students concerning an offense typified into the Colombian criminal code: non-compliance with the food quota. For students to be able to come up with a final analysis of an actual legal case, they followed the pedagogical cycle consisting of analyzing, evaluating, and creating (see Figure 3). (Figure 16)

Note. Slides provided by students enrolled in the legal English classes.

Figure 16 Example of an offense analysis conducted by students

In this case, students analyzed how non-compliance with the food quota is prosecuted, bearing in mind the Colombian criminal code. To do so, they consulted the code mentioned earlier and provided key ideas on food quota, the offense scope, the potential perpetrators, and the penalties awarded. Afterward, they evaluated the current legal procedure’s viability and proposed to penalize this misconduct.

6. Conclusions

After implementing a HOTS-based approach in ESP (Legal English), the researcher concludes that the process was valuable because students could reflect on a two-year English learning experience and assess its benefits and outcomes. Consequently, they realized that English classes provided them with lifelong learnings correlated to developing higher thinking and their future performance as lawyers. In this regard, this study offered students insights into the conceptualization and applications of HOTS. It provided evidence about the significant outcomes of HOTS-based legal English lessons to guide students to take action regarding their lifelong learning process. In this sense, this study responds to the gap mentioned by Johansson (2020) and Köksal & Ulum (2018) in terms of the inclusion of HOTS in English classes and provides useful insights into pedagogical strategies associated with HOTS that may be implemented in ESP courses. In dealing with HOTS in ESP courses, this study also aligns with Ferrando’s notion of the foreign language as a tool to develop more than communicative competence in the foreign language. In this case, the domain is in a specific terminology, as it is the nature of ESP courses, and the inclusion of HOTS complements it.

Furthermore, this study shed light, on the one hand, on the requirements to become higher thinker teachers, and on the other hand, on the necessity to efficiently support students in thinking higher and advancing on the way to growing awareness of their roles as professionals and citizens. This study poses the question of becoming higher thinker teachers in order to promote HOTS in EFL and ESP. However, to achieve this objective, teachers should also be part of communities of practice and training programs intended to equip them with basic tools to begin exploring ways to embed EFL or ESP, according to the case, and HOTS. Furthermore, having the opportunity to conduct HOTS-based English classes allows teachers to have a better picture of their students’ capacities, weaknesses, and potentials and make a more appropriate contribution to their learning process.

Throughout the present research, students challenged themselves in analyzing legal cases, working collaboratively, and proposing solutions based on facts. They could participate in different pedagogical strategies aligned to HOTS and grow aware of the relevance and usefulness of HOTS in real-life settings. Higher thinking has gradually grown as a concern within the TEFL field; nonetheless, there still needs to be more evidence of how internalized is the conceptualization of HOTS beyond the English lesson itself. Throughout this study, students advanced in applying HOTS while resolving in-class activities. Little by little, they became aware of the class phases, namely, the analysis stage, the evaluation stage, and the creation stage. Consequently, they became acquainted with HOTS’ role in their development as human beings, future lawyers, and citizens. Nevertheless, deeper and more extended exposition to HOTS-based activities is necessary, not only in EFL or ESP classes but also in other subject matters, as students are not sufficiently aware of the depth of thought and reasoning processes behind analyzing, evaluating, and creating. In this regard, this study provides a preliminary view of students’ understanding and application of HOTS. The findings reveal that they found a HOTS-based pedagogical approach to ESP useful for gaining lifelong skills and being able to perform in legal contexts using English, but some knowledge gaps still remain.

Regarding further research, various areas of inquiry may arise, such as replicating this study in other ESP courses as a way to compare different professional profiles and the way they understand, internalize, and even associate HOTS with their own field of study. In this research, data collection instruments were not adjusted for further gathering of information. Thus, a replication of this study may include changes to data collection in order to refine and assure better traceability of students’ development and understanding of HOTS. Furthermore, this study does not respond to the role of the foreign language in the development of HOTS, which remains an area for further research along with the implementation of other HOTS frameworks in ESP courses (e.g. Webb’s DOK, Wiggins & McTighe’s taxonomy, Manzano & Kendall’s approach or Dee Fink’s taxonomy of significant learning, among others).