Introduction

Reviewing previous literature regarding the teaching of English as a foreign language (TESOL) in Chile and 'SIMCE de Inglés' test results, this multi-method research explores the unequal access to English language learning (ELL) observed in public and private sector secondary schools from seventh to twelfth grade in the northern Chilean province of Copiapó. Factors such as the number of students per class, the number of teaching hours per week during which students are exposed to the language, among other aspects, are reflected in the results of the 'SIMCE de Inglés', a standardized nationwide graduation exam introduced in 2004. Access to foreign language learning is associated with socioeconomic status in Chile, and the aim of this study is to explore the socioeconomic factors that may have an impact on English language learning in public and private sector secondary schools in the province of Copiapó, by drawing upon 'SIMCE de Inglés' national evaluation test results, and upon the experiences of English language teachers themselves.

In order to be part of the global economy, since the early 2000s Chilean governments have signed free trade agreements with many nations, such as the United States of America and Canada, among others (Harvey, 2007). The major obstacle to the implementation of such agreements was the paucity of English speakers within the labor force. This issue delayed the arrival of international companies in the country, as well as the investment and economic growth they bring to the local economy. Thus, there was an urgent need to train an English speaking workforce able to meet the requirements of a global economy which communicates through the contemporary lingua franca, English (Torrico-Ávila, 2016). This urgent need to increase the teaching of English among Chilean students led to the introduction and implementation of a language policy with the specific goal of mandating the teaching of English as a foreign language, as part of the national curriculum. Known as 'Decreto 81', this language policy defines the plan to teach English in Chile to all students, from the fifth grade of elementary education until graduation from high school. The ultimate aim of the plan was to further the nation's development and its insertion into the global economy. However, these efforts have had the effect of deepening class divisions in Chile, since access to quality education is linked with socioeconomic status. The origin of this class division can be traced to the neoliberal model introduced in Chile during the military regime (Harvey, 2005, 2007). In this context, equal access to English language learning was affected by considerations associated with the social class differences that permeated the educational system. Access to education in Chile is associated with social class (Matear, 2007a). The educational system is divided into municipal public schools, paid for by the state, private subsidized schools, paid for by parents and the state, and wholly private schools, paid for by parents whose salaries are sufficient to meet the costs of high school tuition fees. The outcome of this situation is that English language acquisition functions as an indicator of social differentiation (Byrd, 2013; Torrico-Ávila, 2016), since 'SIMCE de Inglés' results featured prominently in students' résumés mark the beginning of unequal competition. In this context, we maintain that inequality of access in Chilean education is the result of societal social class divisions, enhanced by the market-oriented education established by post-military governments (Matear, 2008).

Believing that there exist differences in terms of the quality of the English language classes provided by public and private sector high schools in the province of Copiapó, which negatively impact the exam results and competency of students, in order to research this topic, we contacted the forty English teachers in the province of Copiapó and asked them to complete an online survey. The province of Copiapó is composed of Copiapó, Caldera and Tierra Amarilla. While the results of this study may seem obvious, in fact no previous research in this field has been conducted in this province, making this study even more relevant to research in the field of English Language Teaching (ELT), and the enabling of a better understanding of the factors that may lead to differences in access to English language study among all Chilean students. At the same time, it offers evidence of how students from different socioeconomic backgrounds perform under the current language teaching policy, as defined by the 2004 'Decreto 81' and tested by 'SIMCE de Inglés' results. This multimethod approach provides valid research results, since quantitative and qualitative data can be triangulated in order to produce reliable analysis and interpretation of the information obtained. This research is also intended to contribute to the educational tools designed for English teachers, thereby helping to bridge the gap in "SIMCE de Inglés" test results by minimizing the differences found across educational institutions, in terms of teaching activities.

Theoretical framework

In order to contextualize this research, it is necessary to review relevant information regarding ELT associated with the political, economic and social aspects which, in turn, influence English proficiency outcomes in Chile. Therefore, we will rely on the work of authors such as Matear (2007a, 2007b, 2008), Menard-Warwick (2008, 2009), Byrd (2013), McKay (2003), and their contributions to a solid understanding of the issue at hand. In order to achieve our goal, we will organize this section as follows: a) Education for a global world; b) The Focus of ELT as a means of economic growth in Chile and social stratification in Chile; c) Chilean educational reforms and the impact on ELT; and, d) English teaching policies in Chile and the 'SIMCE de Inglés' exam.

Education for a global world

Byrd (2013) offers a definition of globalization as "sharing information, for example, ideas, technology and culture in a worldwide scope" (p. 6). Globalization demands a universal language, or lingua franca. For his part, McKay (2003) maintains that many countries promote ELT in the context of national export-oriented economic policies, designing education as a means to develop and improve their economy in the global market. According to Rohter (2004), the minister of education for the government of President Lagos, Sergio Bitar, described the learning of a foreign language, in this case English, as a tool to aid in national development, given that it improves the educational training of citizens with the goal of increasing foreign exports.

Moreover, English promotes 'effective communication' in the exchange of information between countries (TESOL, 2007). According to Menard-Warwick (2008), English has been used as an instrument of globalization closely associated with the international free market economy, and with the relationships between countries worldwide (pp. 1-2). This approach contrasts with the humanistic approach to language, not only by exploiting language acquisition and transforming it into a tool for economic development, but also by commodifying it through the business of English language textbooks, exams and institutes (Torrico-Avila, 2016).

In this vein, Ricento's (2012a, 2012b) understanding of language policies and the effect they have on societies is in line with the arguments proposed by this research, given that both agree on the relevance that language policies have not only on the life of other languages within a given context, but also on the educational and employment opportunities that citizens may access. While Bruthiaux (2002) argues that it is more economically relevant in low income countries to learn the native language, rather than English, Brutt-Griffler (2005) maintains that people should learn English if it can aid in the alleviation of poverty, and Pennycook (2004) thinks that competence in English and another skill can help individuals to succeed in a globalized economy. At the same time, Blommaert (2009) disagrees with these scholars, adding that successful skilled professionals with a strong accent in English have limited job opportunities; thus, English as a tool for personal and national economic development is dependent upon individual circumstances and conditions, and cannot be contextualized according to more generalized factors.

ELT as a means of economic growth and social stratification in Chile

Chilean leaders have used education as a means to increase national economic production through education policies. In 2004, ELT was implemented in public schools as a mandatory subject from fifth grade in elementary school through the final year of high school (Decreto 81/2004). As Byrd (2013) has pointed out, Chilean leaders' goals have focused principally on the country's integration into the global economy (p. 4). These politicians have understood that in order to achieve this aim, citizens should be educated through ELL, because as a global language English opens up access to communication, information and the exporting of products (Rohter, 2004).

The fact of Chile's integration into the global economy through the process of globalization is regarded as positive by Glas (2008, p. 112), who also maintains that increased access to ELT serves to democratize opportunities for access to the English language. This was the goal of the 'English Opens Doors Program', under Decreto 81/2004, which is an improved version of the 'Chile bilingüe' program. However, we remain skeptical regarding equal access to foreign language learning in Chile, given the country's strong neoliberal composition, which has permeated every aspect of the social, economic and cultural life of the community, and this leads us to ask the following question: Is the English language accessible to all citizens in Chile? In order to address this question, it is essential to understand the current neoliberal Chilean context. Glas (2008), aware of social disparities (Harvey, 2007), highlights the two conflicting factors which impact the educational environment in Chile: economic growth and inequality in access to education (Bordel, 2020). While the government advocates for economic betterment, the cost falls upon the citizenry, in a context in which the structure of the Chilean educational system stresses social class divisions. Chilean education is controlled by the Ministry of Education. This entity is responsible for standardizing the educational structure, from pre-school to high school education, in terms of time, content, objectives, skills, etc. It also classifies institutions into three types: state or public, private-subsidized, and private. Because education in Chile is a commodity, elite groups are able to access better educational opportunities. In her work, Matear (2007a) focuses extensively on the differences created by social divisions, citing public and private schools as evidence of such divisions (p. 102).

Public and private schools have contrasting teaching and learning environments. Education in public schools is given to the poorest sectors of the country's population, while private schools cater to the upper classes, who therefore receive a higher quality of education (Matear, 2007a, pp. 103, 105-106; Glas, 2008, pp. 117-118). While public schools teach English in Spanish to a classroom of at least 45 students for 90 minutes per week, in private classrooms there are no more than 20 students per class, with more frequent access available to classes taught by native speakers, for at least 5 hours per week. Thus, exposure to the language and the opportunity to communicate in English is greater. The results of a study conducted by McKay (2003) have shown that public schools prefer bilingual teachers because they are conscious of the students' economic reality. Conversely, private schools prefer native speaker teaching staff because of the perceived prestige given to native speaker-like pronunciation (pp. 144-145). This is why McKay (2003) believes that the teaching of English, as an international language, is appropriate in the national context, as it takes students' daily reality and culture into account when designing methodological approaches.

Chilean educational reforms and the impact on ELT

National governments believe that English as a Foreign Language (EFL) helps to improve prospects for their citizens because a command of English increases employment and educational opportunities (Byrd, 2013, p. 25; Niño-Murcia, 2003, p. 183). Thus, English is regarded as an important tool for improving access to employment (Delicio, 2009, p. 89). This view is supported by the educational reforms implemented in Chile, such as 'Decreto 81/2004', introduced by the government of Ricardo Lagos and overseen by his Minister of Education Sergio Bitar, as well as the 'Ley Orgánica de la Calidad de la Educación', 'Ley 20.370' or 'Ley General de Educación' ('LGE'), and the 'Estrategia Nacional de Inglés 2014-2030'. All these initiatives place English in a strategic position within the curriculum, establishing teaching hours and including a foreign language examination in order to measure national results and facilitate further improvements in the program.

Under the provisions of 'Decreto 81/2004', the current English language policy is expected to consolidate economic international ties with the United States, Europe and Asia, through free trade agreements involving an English-speaking workforce. It is through such ties that Chile is able to participate in the global economy and exploit new economic opportunities, as stated by the former Minister of Education, Sergio Bitar:

We have some of the most advanced trade agreements in the world, but that is not enough. We know our lives are aligned more than ever with an international presence, and if you cannot speak English, you cannot sell, and you cannot learn [sic] (Rohter, 2004).

With government intervention in EFL, an increase in employment opportunities and an improvement in the lives of Chilean citizens could be generated (Byrd, 2013, p. 25). Under the Bachelet government (2006-2010), there was an amendment to 'LGE', with the modification of certain provisions of the law in order to focus on creating an educational system characterized by equity and quality in its service to society, with the inclusion of knowledge of a second language accessible to all (Law 20.370, 2009, pp. 1-10). Article 3 states that one of the rights and principles of Chilean education is quality, under which each student must attain every general objective and learning standard imposed by this law, regardless of their condition or circumstances:

Equity in the educational system. The system will seek to ensure that all students have the same opportunities to receive a quality education, with special attention given to those individuals or groups requiring special support (Law N° 20.370, 2009, p. 2).

This is a key point, because quality of education is subject to prevailing social class divisions (Matear, 2007a, pp. 102-103). Matear (2007a) questions these provisions, maintaining that such characteristics are not present in the educational system, given that receipt of a quality education remains dependent upon the economic resources of an individual student's parents or guardians (pp. 105-107).

English teaching policies in Chile

Under 'Decreto 81/2004', English teaching policy incorporates the program known as the 'English Opens Doors Program' (EODP). The program includes: English Summer/Winter Camps and English Summer Town/ Winter retreat activities; nationwide training of teachers; the voluntario angloparlante system; the national 'SIMCE de Inglés' exam; spelling bee competitions; and teachers' networks. According to the Chilean Ministry of Education (MINEDUC), the purpose of this program is to regulate the time Chilean public school students spend studying English, while also standardizing the ELL materials used by teachers. The provisions of Article 2 regulate such activities:

Article 2: The goal of the program is to improve the level of English learned by students from the fifth grade of elementary school to the fourth grade of high school within the subsidized educational system, in accordance with Decree N° 3.166, 1980 and the provisions for the defining of national standards for the learning of English, professional teacher development strategy, and support for English teachers in the classroom (Decree 81, 2004, pp. 1-2)6.

Having incorporated 'Decree 81/2004' into the educational system, Bitar (2004) argued that the English Language Policy was 'an instrument of equality for all children in Chile' (p. 4). The minister went on to comment that the decree took into account working class families, by striving to bridge the gap opened up by the neoliberal economic model, in the form of social class division. This is evidenced by the curriculum implemented: in accordance with the policy, English is a compulsory subject from fifth grade in Chilean public schools, but private schools teach English from pre-school (Torrico-Ávila, 2016).

According to Rodrigo Fábrega, the director of the education ministry's EODP from 2004 to 2008, one of the weaknesses of the program is the lack of qualified English teachers in Chile. Therefore, the success of the program is reliant upon the training of "an army of English teachers" in the 'Chilean-style', meaning language learning used as a tool for understanding content, while relegating to second place other aspects of the language (Rohter, 2004).

'SIMCE de Inglés'

According to Ortiz (2010), 'SIMCE' has its origins in the 1980s, under the name Programa de Evaluación del Rendimiento (p. 1). Matear (2007a) maintains that the contribution of 'SIMCE'is of great importance in Chilean education because of its reporting of indicators, such as socioeconomic data (low, lower-middle, middle, upper-middle classes) and average scores by schools (municipal, subsidized-private, and private schools) (p. 103). Additionally, the information collected as part of the 'SIMCE' results categorized the schools throughout Chile in order to give feedback on what the students learned, as well as providing information about students' socioeconomic groups, and how they would function in the global economy (Ortiz, 2010, p. 2; Matear, 2007a, p. 103). This measurement method provoked criticism, not only within the educational field, as well as to the stigmatizing of teachers, school management and the students of those schools where results were low (Ortiz, 2010, p. 2). This phenomenon also permeated the 'SIMCE de Inglés' exam results, a test which was implemented from 2004 until 2018. This exam is the ALTE test, overseen by the Association of Language Testers in Europe, and also forms part of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR). An example of the quality stratification can be seen in 'SIMCE de inglés' results for 2010, when it was found that 11% of third-year high school students in public schools only understood everyday phrases and short texts in English, and that 89% did not achieve the basic level for certification in English (La Tercera, 2011).

Among private schools, exam results were as follows: Nido de Águilas, 100% accreditation at the required English level; in second place, the subsidized private school Patagonia College de Puerto Montt, with 72% accreditation at the required level; in third place, the Hispano Britanico school in Iquique, with 70% accreditation; in fourth place, the public school Liceo Carmela Carvajal, with 58% accreditation; and in fifth place, the Instituto Nacional, with 57% accreditation (La Tercera, 2011).

As a result, according to the report 'Objetivos fundamentales y contenidos mínimos obligatorios de la educación básica y media' (2009) and 'Fundamentos bases curriculares 2011' produced by MINEDUC, ELT enables students to access a more prosperous future, with proficiency in English helping them in the workplace (p. 85, p. 42). To achieve this goal, students must actively collaborate in the learning process, expressing their opinion in English. Nevertheless, the 'SIMCE de Inglés' results contradict these reports, because the main goal is clearly not being achieved; namely, the development of language learning skills in the classroom (The Clinic, 2010; De Améstica, 2013; La Tercera, 2011). In fact, students' results are not in line with the B1 level of comprehension established by CEFR for their final year of high school, and by MINEDUC in their own document, 'Bases curriculares 3.° y 4.° medio' (Unidad de Currículum y Evaluación, 2019, p. 76).

It should also be noted that this research focuses on a comparison between public and private schools and the implementation of the national curriculum to teach English in Chile, which is standardized and follows the provisions of the 'English Opens Doors Program' language policy, a continuation of the program originally known as 'Chile bilingüe'. Policies, curriculum, institutions, types of education and examinations all fall under the domain of the Ministry of Education, and therefore the factors, components, strategies and results we are focusing on also fall under their remit. External factors, such as access to extra classes provided by language institutes, are not included in this research. Also, the data collected for this study is mainly in the form of policy documents and regulations. Subjects were interviewed regarding their experience in face-to-face instruction, because the latest available 'SIMCE de Inglés' results date from 2018, before the 2019 Chilean social uprising and the 2020 health crisis. Therefore, the social uprising and the impact of Covid-19 are not taken into account, due to the absence of measurable evidence for the impact of these events on ELT.

To summarize, when reviewing previous literature, we identified a lack of awareness and knowledge gap regarding unequal access to ELT in high schools. In the following sections, we will focus specifically on exploring the reality in the province of Copiapó.

Methodological framework

Since 2003, successive Chilean governments have pursued the goal of greater participation in the global economy and the achieving of improved opportunities in a globalized world. Language is a key component in forming part of the international economic community, and English is the lingua franca (Byrd, 2013, p. 6). In the current globalized market, it is language that is the tool which enables societies to achieve their goals in terms of education, economic growth and trade (Byrd, 2013, p. 9). In order to make such goals a reality, in Chile local governments delegated this task to the Ministry of Education. The aim was to train an army of English speaking Chilean citizens, because the absence of a Spanish-English bilingual population was identified as the reason why international companies were reluctant to base themselves in the country. Such companies were expected to arrive once free trade agreements had been signed between Chile and several countries, including the United States and Canada (Torrico-Ávila, 2016).

In order to train this Spanish-English bilingual force, MINEDUC, through the 'Chile bilingüe' program, reinforced the EFL syllabus within the Chilean national curriculum. Changes included initiating exposure to EFL from fifth grade in elementary school to the fourth and final year of senior high school. The number of study hours over those years would result in an intermediate level of competence in English, which would be reflected in the 'SIMCE de Inglés' national examination.

However, as we outlined in our theoretical framework, we addressed equal access to English language learning with a focus on the social class differences that permeate the educational system, meaning that access to quality education in Chile is associated with social class (Matear, 2007, 2008). The Chilean educational system is divided into state schools, priva-te subsidized and private schools. This results in proficiency in the English language being perceived as an indicator of social difference (Byrd, 2013; Torrico-Ávila, 2016) since 'SIMCE de Inglés' results feature prominently in students' résumés, marking the beginning of unequal competition. In this context, we maintain that inequality of access in Chilean education is the result of societal social class divisions, enhanced by the market-oriented education established by post-military governments (Matear, 2008). Therefore, we hypothesized that there existed inequalities in access to English language learning between private and public sector high schools in the province of Copiapó.

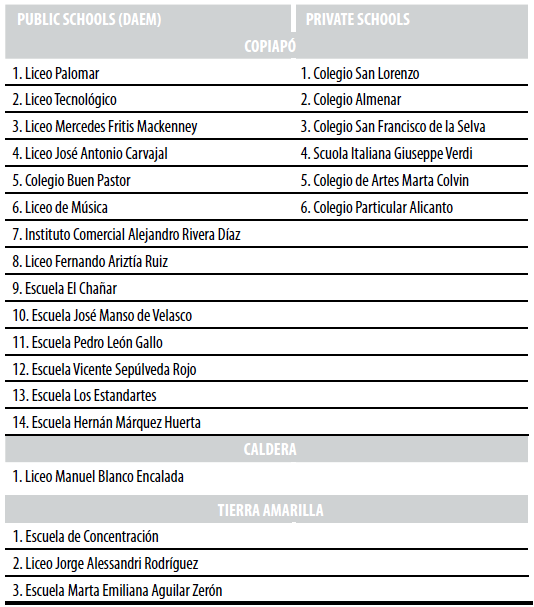

The scope of the research is limited to the province of Copiapó, including the cities of Copiapó, Tierra Amarilla and Caldera, and takes the form of online research supported by the province's English teachers. The subjects of the research were high school English teachers in the province's municipal-public and private schools, during the 2020 academic year.

The goals of the research were divided into general and the following specific objectives, which are: 1) Overall aim: explore the socioeconomic factors that may have an impact on English Language learning in public and private high schools in the province of Copiapó, based on the 'SIMCE de Inglés' national evaluation results and English teachers' experiences. The specific aims are: 1) Observe English language results of the 'SIMCE de Inglés' national examination in public and private high schools in the province of Copiapó; 2) Examine how economic factors might impact English language results in public and private high schools in the province of Copiapó; 3) Explore English language teachers' responses regarding ways to address unequal English language teaching conditions in public and private high schools in the province of Copiapó. The research questions that emerge from these specific aims are: 1) What are the differences in the 'SIMCE de Inglés' results between public and private schools in the province of Copiapó? 2) What are the economic factors that may influence English language learning results in the public and private high schools of the province of Copiapó? 3) What do English language teachers suggest in order to make ELT access as equal as possible for every student in public and private high schools in the province of Copiapó?

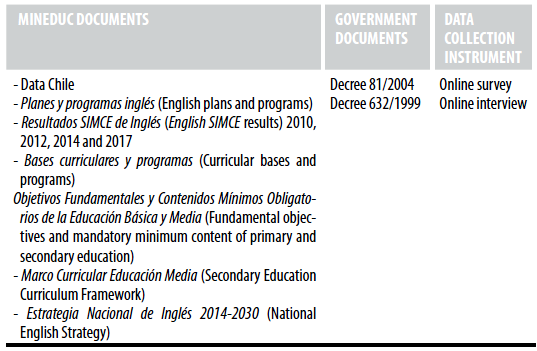

The design of this research takes the form of a multi-method approach, consisting of a survey and the analysis of documentation. Validity and reliability are ensured by the triangulation method. Quantitative and qualitative data were obtained from the following documents:

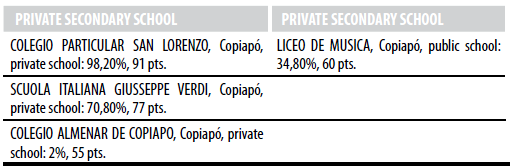

The public and private sector high schools of the province of Copiapó are listed below:

The subjects of this study were 40 teachers from the public and private sector high schools of the province of Copiapó, composed of 32 women and 8 men, whose ages ranged from 24 to 66. They shared their experiences, difficulties and differences regarding teaching English in both types of educational institutions. In addition, they were asked to apply their cultural understanding, professional skills, methods and strategies and techniques, gained from their own teaching experience, in order to suggest activities that would help bridge the gap between the two types of institutions.

Two data collection instruments were employed in the research: 1) An online survey applied to EFL teachers from public and private sector high schools in the province of Copiapó, and 2) Documentary archives. The online survey provided information to complement the data gathered from documentary analysis.

The procedure employed to conduct the research was the application of an online survey to English teachers from public and private sector high schools in the province of Copiapó, in order to collect information regarding their teaching and how they engaged with strategies and activities in the classroom. In addition, we conducted archival research. We examined the MINEDUC and other government documents regarding the teaching of English in Chile. From those, we selected extracts which addressed inequality in ELT, employing them as research data, which was then analyzed and discussed in the results and discussion sections of our study.

Results

In the following section, we will set out the results obtained from our multi-method research. The outcomes were divided into subsections: a) Qualitative results composed of 'Decreto 81/2004' and 'Decreto 632/1999', 'Bases curriculares', 'Planes y programas de estudio', 'Objetivos fundamentales y contenidos mínimos obligatorios de la educación básica y media', 'Marco curricular educación media', 'Estrategia Nacional de Inglés 2014-2030' and interview results; and b) Quantitative results taken from 'SIMCE de Inglés' test results, survey results, DataChile and educational documents provided by MINEDUC. The findings were as follows:

Qualitative Results

In this subsection, we list the qualitative results obtained through the data collection. These will be analyzed in the discussion section.

The extract from 'Decreto 81/2004' explains the benefits of learning the English language in Chile, through the equality that the education system ought to guarantee.

Extract 1

[...] people who possess a basic and functional competence in [English] will have better employment and salary opportunities, be more successful at the university, be able to apply for scholarships, start an export business, and access new information via the internet, among many other advantages and opportunities (Decreto 81, 2004, p. 1)7.

In a similar way to Extract 1, Extract 2 provides an explanation of the purpose of ELT in the Chilean context, as described in the document 'Fundamentos Bases Curriculares 2011', contained in the 'Unidad de Currículum y Evaluación' (2011). It outlines the benefits students who learn English can gain in their lives by developing their language skills.

Extract 2

Within this context, the purpose of English as a foreign language subject is that students learn the language and use it as a tool to interact in their everyday lives, in communicative situations, and also when accessing new information. To achieve these goals, students are expected to develop the four English language skills (listening comprehension, reading comprehension, written and oral expression), through meaningful and authentic communicative tasks. At the same time, students are expected to develop cognitive skills that will help them to develop, organize and internalize the information they are able to access through proficiency in English ('Unidad de Currículum y Evaluación', 2011, p. 78)8.

Extract 3 features a response from an interviewed teacher. The teacher elaborates on the differences between public and private sector institutions in the province of Copiapó:

Extract 3

In my opinion there are a lot of differences between these kinds of schools: Private schools: Family engagement with studies, good resources (teachers, books, pleasant classrooms, fewer students in each class, foreign volunteers), school environments conducive to the learning of a second language, where students can use English. Disadvantages of public schools: knowledge and cultural development in the family, unemployment among students' family members, poor attendance, little motivation among students to learn English as a second language, lack of graduate teacher training, problem behavior among students, lack of technology in the classroom to assist with the learning process (see Appendix 2).

In Extract 4, the interviewed teacher suggests some activities that would, in his/her opinion, help to reduce the inequalities in the teaching of English between public and private sector schools in the province of Copiapó.

Extract 4

I believe that as teachers we need to know how to combine several types of strategies in order to find those which are most effective for each group of students. TPR9 can be used equally in both municipal and private schools, but some institutions may not have the sufficient resources or installations, and the same problem may be encountered when employing strategies in which we would need to use TICS10. Conditions may vary from school to school. In conclusion, I think that we need to do what we can with the resources we get. I mean, we can engage in the same activities in both types of establishments, but the resources we will use will be different. That is when we need to use our intelligence and know how to improvise (see Appendix 2).

In the following extract, the teacher argues that the issues associated with the differences in the education provided by the two types of institution are complex, and that more is needed beyond suggesting activities to bridge the gap:

Extract 5

I am not sure that designing an activity would be enough to standardize the teaching of English in both types of institution, because the issue is more complex and needs to be examined from the roots of the education system; that is to say, when the students begin preschool, parents must be encouraged to have a participatory attitude in the educational process, which must then be maintained up to graduation (see Appendix 2)11.

In Extract 6, the teacher interviewed suggests collaborative efforts between public and private sector schools as a way to solve the problematic gap:

Extract 6

There needs to be collaboration between public and private schools: singing contests, talent shows, spelling bees, public speaking, debates, theater, etc. Social work, sponsoring schools, work on community projects (see Appendix 1)12.

In Extract 7, the teacher recommends some materials, activities and modifications to the current system for teaching English in the province of Copiapó:

Extract 7

Gamification (pedagogical games using modern technology), preparation and access to international English exams (Cambridge exams), different teaching strategies in classes, different methodologies (project-based learning), use of English text books focused on higher levels of English (A1-A2) or English International Exams, provision of more hours of English per week, inviting students to be part of local initiatives in order to get them more involved in the subject (see Appendix 2).

Quantitative Results

In this subsection, we list the quantitative results obtained through the data collection. These will be analyzed in the discussion section.

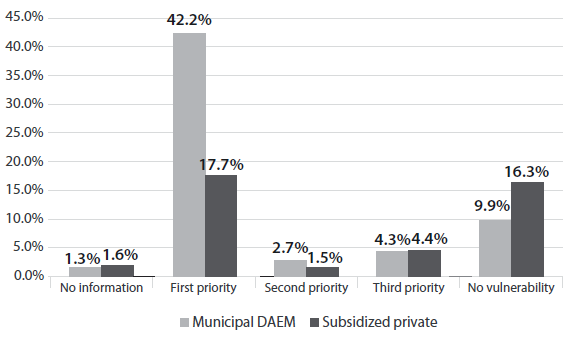

The following figure provides information regarding the vulnerabilities present in the schools situated in 'El Departamento de Administración de Educación Municipal' (DAEM) of the Atacama region, which contains the province of Copiapó. The classifications range from "first priority", being the most vulnerable, to "not vulnerable". Figure 1 shows that 42.2% of the municipal schools are first priority, while 17.7% of the subsidized private schools are first priority. The figure also illustrates the major differences in the vulnerability of municipal schools compared to those of the region's private schools.

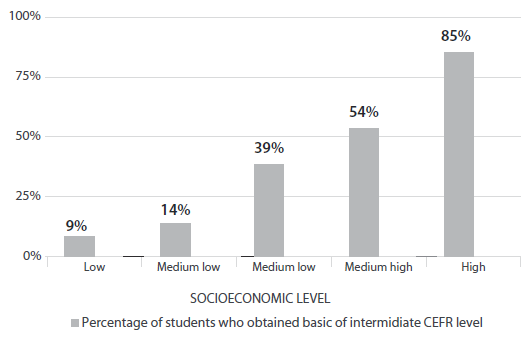

Figure 2, below, contains information on 2017 'SIMCE de Inglés' results. The percentage of Chilean students who obtained from basic to intermediate levels (A2 and B1) of English, according to CEFR, varies from 9% to 85% due to their socioeconomic groups (from low to high), as indicated in the following graph.

Source: Agencia de Calidad, 2017, p. 10

FIGURE 2 Percentage of students who obtained basic or intermediate CEFR levels in Chile per their socioeconomic levels, according to 2017 'SIMCE de Inglés' results

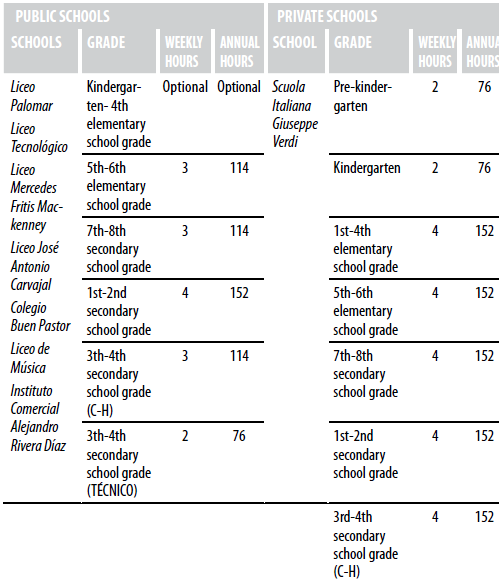

Table 1, below, contains the summary of the school course plans available on the school websites, and shows the number of English hours in public high schools in the province of Copiapó. The differences in the number of hours provided in public and private institutions in the province are apparent. In the Scuola Italiana Giuseppe Verdi private school, English instruction begins in kindergarten.

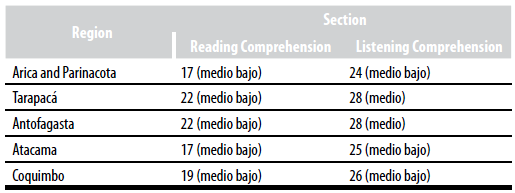

Table 2, below, shows the results for the Reading and Listening Comprehension sections of the 2017 'SIMCE de Inglés' exam taken by students from third year secondary schools in the Atacama region, including the province of Copiapó.

TABLE 2 Average score obtained by region in the reading and listening comprehension sections of the 2017 'SIMCE de Inglés' test

Source: Agencia de Calidad, 2017, p. 12

In Table 3, below, the 2013 'SIMCE de Inglés' results show that only one public school on the list achieved the level of competence required by MINEDUC, which is basic to intermediate. Contrastingly, three of the region's and province's private schools achieved certification level.

Discussion

Regarding the results set out in the previous section, we can conclude the following: First, there exists the promise of employment, economic development and educational opportunities for students who learn English (See Extract 1), on the part of the state and MINEDUC, through the English language policy as defined by 'Decreto 81/2004'. That promise also claims to offer the possibility of communicating in everyday contexts and learning new information by using the English language (see Extract 2). However, in the Results section, Table 3 and Figure 2 demonstrate that according to the 2013 and 2017 'SIMCE de Inglés' results, there is a difference in the English language levels achieved by students in the public and private schools of the province of Copiapó. Table 3 makes it clear that only one municipal school made it onto the list of schools that achieved the level of certification in English established by the government, whereas three of the province's private schools achieved that level. As of 2017, economic considerations were a crucial factor in language certification. Figure 2 shows that 70% of high income institutions achieved the desired level of English language certification. For the Atacama region, where the province of Copiapó is located, Table 2 contains detailed information on the average level of certification achieved. In fact, Atacama has the lowest results in northern Chile, achieving only grades classified as 'medio bajo'. This average is explained by the small number of private schools in the region, which are so few in number they are unable to compensate for the low performing results obtained by the other schools in the region.

With regard to the economic factors that may influence the teaching of English in the province of Copiapó, teachers have shed some light on the issues. In Extract 3 of the previous section, a teacher shares the reasons why she believes there exist differences between public and private education. According to her, the number of English teaching hours per week, number of students in each class, parental or guardians' support for students' activities and native speaker interaction are the key factors influencing results in the national examination. These factors negatively affect public schools, where they have only 2 hours of English per week, at least 45 students per class, and family or personal problems among students. The Atacama region exhibits a high level of vulnerability to such factors, which places it in the 'first priority' classification, as shown in Figure 1. Extract 3 provides information concerning differences in the number of teaching hours per week between public and private secondary schools in the province of Copiapó. Table 1 contains full details on the number of teaching hours per school, showing that public institutions follow MINEDUC regulations in the number of hours, providing 76 hours per year, whereas the area's private schools teach more hours than required by MINEDUC, providing 152 hours per year. As we have shown, frequency of exposure to the English language contributes to good exam results, as evidenced by the outcomes for A1 to B1 CEFR English level certification (see Figure 2 and Table 2).

Regarding comments made by English language teachers in the Province of Copiapó concerning ways to bridge the gap in 'SIMCE de Inglés' test results, Extract 4 provides a list of suggestions, such as combining teaching strategies, using TPR activities as well as TICs, and being more creative in terms of individual teaching methods. In the same vein, Extract 5 contains practical activities that public secondary school teachers could employ in order to improve national test results, such as community projects and social work. Such activities complement the work that already forms part of the 'English Opens Doors Program', such as spelling bees, public debates, and talent shows, for example. Of particular interest in Extract 6 is the proposal for implementing a system that would enable private schools to sponsor their public sector counterparts' English teaching activities. This suggestion may be something that could be considered and explored as part of further research in this field.

Conversely, other teachers have expressed skepticism regarding the possibility of improving English exam results through activities and teaching strategies. Rather than supporting activities and strategies to address this problem, they argue (see Extract 5) that the issues are more complex, and that solutions should be sought in the foundations of the educational system. They also maintain that students' and parents' attitudes play a crucial role in the learning process, and that parental support must be maintained right through to graduation.

In conclusion, in this section we have attempted to address the questions that led this study, exposing how economic factors influence the type of education parents can afford and how that affects the national problem of 'SIMCE de Inglés' results. Because no previous data was available for the province of Copiapó, this research has attempted to fill that void.

Conclusion

The aim of this research was to explore the socioeconomic factors that may have an impact on English language learning in public and private sector high schools in the province of Copiapó, by analyzing 'SIMCE de Inglés' national evaluation results, as well as English teachers' own individual experiences. In order to achieve this goal, we designed a multi-method project that included analysis of MINEDUC documents, as well as the conducting of interviews and a survey, in order to facilitate the triangulating of data. Our results have shown that 'SIMCE de Inglés' exam scores for the province of Copiapó are closely linked to the degree of economic access experienced by students across public and private schools.

The strengths of this research lie in the inclusion of data regarding 'SIMCE de Inglés' results in the province of Copiapó, as well as in the exploration of influencing factors. The principal limiting factor of this study is the limited information regarding the individual results of each of the region's institutions. Such information would enable teachers to plan remedial programs designed to improve individual student outcomes. In conclusion, while this research has contributed information regarding the economic differences that influence English exam results in the province of Copiapó, further research will be required in the Atacama region in order to minimize the discrepancies in results, while in addition teachers' suggestions should be considered, with regard to exploring how collaboration between private and public sector high schools in a sponsoring system might improve the 'SIMCE de Inglés' results of public schools, thereby helping to resolve what is, at its root, an issue of inequality.