Introduction

Since the 1990s, an interesting phenomenon has been taking place in Latin America that calls into question the so-called "Theory of secularization", referred to in other contexts as the "end of secularization theory" (Joas, 2007, pp. 9-43, in Habermas 2008a, p. 2). This theory proposes as the ultimate stage the secularization of society, a process through which its religious elements are progressively lost (da Costa, 2008). According to Jürgen Habermas, this progressive decay -which, according to theorists such as Max Weber and Emile Durkheim occurs at the same time as modernization- would be characterized by the progress of science and technology, by the loss of the political, social, and cultural influence of religious groups of different kinds, and by the security and increase in social welfare experienced in a post-industrial world (Habermas, 2008a, p. 4; 2008b).

The current context of Latin American politics, on the contrary, would rule out such secularization and show that there is a "process of religious resacralization" (Krech, 1999, in Ihrke-Buchroth, 2013, p. 11) and a "revitalization of old living traditions" (Casanova, 1994, p. 225, in Ihrke-Buchroth, 2013)3. This could be framed in what Habermas calls "post-secular society" (Habermas, 2008a, p. 4; 2008b). For him, three overlapping phenomena give "the impression of a "global resurgence of religion"" (Habermas, 2008a, p. 5): the missionary expansion of orthodox or conservative groups of already established religions such as Hinduism, Buddhism, Catholicism, Islam and evangelicalism (the latter especially in Latin America); the rapid growth of religious movements; and the political radicalism of some religious groups such as the Islamic State (Habermas, 2008a, pp. 5-6). In the face of this challenging context, what the Frankfurt School thinker proposes is a space of "mutual respect" (2001), of "egalitarian respect" (2008a) or of "mutual recognition" (2008b) where "each spiritual family participates in the public sphere" accepting the neutrality of the State (Niño Castro, 2012, p. 103).

In my opinion, the intrusion of the sacred-religious into the profanepolitical that this research addresses takes on greater significance if we take the definition of religion by the theologian and anthropologist Manuel Marzal. Based on Durkheim and Geertz, he mentions that "[religion] is a system of beliefs, rites, forms of organization, ethical norms and feelings, through which human beings relate to the divine and find a transcendent meaning in life" (2002, p. 27)4. In this line, and contrary to the "mutual respect" between spiritual families (as well as with the secular sectors of society), it is considered that the rise of "political-religious"5 in the contemporary Latin American political scene would express a new facet in the relationship between Politics and Religion: a facet in which politics would be the tool to reach and relate with the divine.

In the Peruvian case, despite the evangelical demographic growth (to the detriment of Catholicism)6, this is not reflected at the political-electoral level (Pérez Guadalupe, 2018). The participation of evangelical political parties has shown that there is no "confessional vote" in Peru. However, taking into account the last presidential elections (April 2021), it would be possible to speak of an anti-progressive or a conservative-moralist vote due to the heterogeneous character of its voters: the ultra-conservative Renovación Popular party of the Opusdeist businessman Rafael López Aliaga obtained third place with 11% of the valid votes. This favorable result, although surprising to many, was not sudden. On the one hand, because in recent years a transconfessional alliance was formed between various evangelical denominations and the more conservative wing of Catholicism7. On the other hand, because this was the product of the active participation, for more than a decade, of various conservative movements and collectives (Coordinadora Nacional Pro Familia, Red Nacional de Abogados por la Defensa de la Familia, Con Mis Hijos No Te Metas8 , among others) in marches and campaigns mainly against the rights of sexual minorities (Tello Aguinaga, 2019) and which have proven to be strong enough to influence the national political agenda and debate (Mujica, 2007; Fonseca, 2015).

In this context, this article focuses on these conservative Pro-family and Pro-life collectives with the objective of delving into the ideal of society they desire for Peru. It is essential to mention that these groups will be seen from a neo-Pentecostal point of view; therefore, particular emphasis will be placed on their political theology and the (dis)connections that may exist between the two. This approach is due to the fact that, on the one hand, many of their leaders belong to churches of this denomination9. On the other hand, due to the process of neo-Pentecostalization that the evangelical world has undergone. And finally, because of the close relationship of this denomination with a conservative cultural vision and a liberal-nationalist political and economic vision. That is why I also intend to analyze the relationship between Religion and Politics and whether it is possible to speak of an "ethic of prosperity" in these conservative groups.

The fieldwork was conducted on five pages of collectives in favor of the "traditional family", against abortion and the homosexualization of people during three months (October, November, and December 2021): Con Mis Hijos No Te Metas (247 thousand followers), Marcha por la Vida (99 thousand followers), Marcha Por La Familia - Perú (65 thousand followers), Coordinadora Nacional Pro Familia (26 thousand followers) and Red Nacional de Abogados por la Defensa de la Familia (RENAFAM, 7.8 thousand followers)10. The review of these pages consisted, in the first place, in the search for publications dealing with social, political, and economic issues. In addition, these publications had to have a visible amount of interactions (reactions such as "likes", "hearts", etc., and comments); in other words, material to work with. Secondly, I reviewed the comments on each post. Comments that were rich in content were what I was looking for here. Thus, comments that were too short or that, compared to others, did not have such richness were discarded.

Participation in these spaces was the starting point. Once immersed in these groups, future interviewees were sought. Since these groups have many followers, it was thought that finding interviewees would not be a problem. However, most of the people I wrote to did not respond to my messages -not the same users from the review of comments. Near the end of the fieldwork, I got a positive response and the opportunity to conduct an in-depth interview with one of the co-founders of the CMHNTM movement. In this scenario, I had to reformulate the strategy and find a way to obtain more insights into the emic perspective that was fundamental for the research. That is how I decided that I would ask people to answer a survey instead of interviews. I sent this message to more than 100 users from the conservative groups reviewed here, of which only 12 responded.

In the following lines, some central aspects of Neo-Pentecostalism and the political theology of this denomination will be mentioned. Then, the conservative groups on Facebook and some of the methodological aspects of studying them will be discussed. After that, the results of the fieldwork will be presented, i.e., the ideal society (social, political, and economic) that they wish for Peru will be presented. Finally, we will discuss the neo-Pentecostal political theology and pro-life and pro-family conservatism, the presence of a certain "ethic of prosperity" on Facebook, and a possible spiritual war 2.0.

What is Neo-Pentecostalism? Between the sacred and the profane

In the last thirty years, a social and political phenomenon that has attracted attention in the region is the emergence of conservative groups whose leaders are mostly evangelicals, or more specifically, neo-Pentecostals. The participation of these groups in the political arena, their rapid rise to positions of political power and their polarizing discourses have attracted the attention of many people -specialists, political commentators, citizens, etc.- mainly because of the religious aspect that permeates their political agenda, but who are the Neo-Pentecostals, and what are their characteristics?

A brief history of Neo-Pentecostalism in Latin America

In the first decades of the nineteenth century, the presence of Protestant figures in the region could be seen in countries such as Brazil, Cuba, Mexico, and Peru (Pastor Gómez, 2018a, p. 62); however, it was not until the mid-nineteenth century that the first Protestant missionaries will arrive in the region with the aim of evangelizing, educating and meddling in social tasks (Pérez Guadalupe, 2018, p. 24). Most of these missionaries came from denominations that formed in the mid-17th century after the arrival of the Pilgrims in North America and who "believed they were the chosen ones to form an exemplary society and idealized work as a necessary offering to obtain divine blessing and material gains" (Pastor Gómez, 2018a, pp. 57-58).

This idea of "being the chosen ones to form an exemplary society" would be justified with the doctrine of manifest destiny, where it was emphasized that the United States was "God's chosen people destined to expand throughout America" (Pastor Gómez, 2018a, p. 55). Or, in the words of journalist John O'Sullivan in the Democratic Review of New York in 1845: "It is our manifest destiny to extend and take possession of the whole continent which Providence has given us for the development of this great experiment in liberty" (Pastor Gómez, 2018a, p. 59). In this way, the Nation would be seen as a Church that fulfills the divine designs of Christianizing the world and "guiding the rest of the world along the path of progress" (Fonseca, 2002, p. 75). This would be complemented by the "America for the Americans"11 expounded in the Monroe Doctrine, which, as Pastor Gómez suggests, would facilitate the penetration of U.S. American Protestantism in Latin America (2018b, p. 154).

In that context, after having been established in the Congress of Panama in 1916 that Latin America was still a "missionary land" (Pérez Guadalupe, 2017, p. 18), the first expansive and proselytizing wave came from the U.S. American evangelical denominations of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and not from classical European Protestantism (Sánchez Paredes, 2005, p. 87). In 1925, due to the increase in their membership, Protestant churches migrated to the countryside and indigenous communities to carry out their evangelizing project through their "faith missions". Until 1940, it was already possible to speak of a varied evangelical presence -Methodist, Lutheran, Presbyterian, Baptist and Episcopalian. In the 1950s, a more aggressive evangelization was carried out through the systematic use of the media (having as a referent "Billy Graham's crusades", speeches that mixed the preaching of the gospel with an anticommunist political positioning) (Pastor Gómez, 2018a, p. 63).

In the 1950s, communist China cut ties with the United States; this also meant the expulsion of its missionaries (Pérez Guadalupe, 2018, p. 32). In addition, in the 1960s, Liberation Theology arose in Latin America. In that context, Nelson Rockefeller, Nixon's vice president, emphasized in 1969 that the Catholic Church was "susceptible to subversive penetration [by Liberation Theology]" and that it was, therefore, necessary to introduce [in Latin America] "another type of Christian" (Pastor Gómez, 2018b, pp. 155-156)12.

Another denomination that arose in the United States and that was well received in Latin America is Neo-Pentecostalism. In Latin America, for its part, it appears in the 1980s (Pérez Guadalupe, 2018, p. 41). However, it was not from the 1990s that Neo-Pentecostals, despite being a minority, began to "lead" the evangelical movement in the region, which "coincides with the hegemonic expansion of globalized neoconservative political thought" (Pérez Guadalupe, 2018, p. 43). This rise of neo-Pentecostalism would be accompanied by Prosperity Theology, which is, as will be seen below, "a set of dogmatic, ritual and ecclesiological propositions in which a relationship between communion with God and material well-being is affirmed" (Semán, 2005, p. 73, in Jaimes, 2012, p. 659). However, due to the process of neo-Pentecostalization of the other denominations (Tello Aguinaga, 2019, p. 8), "the whole evangelical religious field is crossed by these practices" (Sermán, 2005, p. 73, in Jaimes, 2012, p. 659), which would complicate this element as a distinctive feature of the neo-Pentecostals.

The Peruvian experience

Although in Peru until 1836, practicing cults other than Catholic were punishable by death, since 1822, a certain presence of Protestants could already be seen in the region, for example, with the work of the Scottish Baptist educator and pastor Diego Thomson (James Thompson), invited by General José de San Martín to implement the Lancasterian educational system in Peru (Campos, 2014, p. 2). However, it was only in 1915 that the Peruvian Constitution granted Evangelicals (classical Pentecostals) the right to public worship (Sánchez Paredes, 2005, p. 87).

According to the proposal of Amat y León and Pérez Guadalupe, three stages can be identified in the history of the Peruvian evangelical movement: evangelicals, Pentecostals, and neo-Pentecostals (2018, pp. 409-410). The first stage would be between the late nineteenth century and the twentieth century with the arrival of European missions. In this period, these movements would be characterized by an evangelical leadership that was "basically foreign, missionary and dissident with respect to the position of the large Protestant denominations in the world" (Amat y León and Pérez Guadalupe, 2018, pp. 409-410). Likewise, in this period, the Protestant presence in Latin America and Peru was related to the liberal intelligentsia: while the liberals saw in the Protestants a progressive religiosity that was accommodated to their modernizing project and that was "bearer[a] of cultural values proper to Anglo-Saxon civilizations" (Fonseca, 2002, p. 41), the Protestants saw the liberals as the political force that would grant them the desired freedom of worship.

The second stage began with the arrival of the Pentecostals in Peru at the beginning of the 20th century. At first, this movement was viewed with distrust by the Evangelicals until the Pentecostals began to gain popularity, especially in the countryside and on the outskirts of the cities. This led to a process of Pentecostalization of the Peruvian evangelicals over time, making the Pentecostals the new referents of the evangelical movement (Fonseca, 2002, p. 41). At this stage, to be more precise, during the Leguías Government (1919-30), a period of robust U.S. presence in the Peruvian economy and culture (Gonzales Alvarado, 2015), the relative success of the Protestant missions can be appreciated. This was manifested by the more significant presence of American missionaries (as opposed to those coming from England, Scotland and other countries) (Fonseca, 2002, p. 134).

The third stage would comprise from the mid-1990s to date and would be characterized by the arrival, through middle-class leaders and pastors, of a sector called "neo-Pentecostal" (Amat y León and Pérez Guadalupe, 2018, p. 410). This movement that considers itself spiritually superior to other evangelical groups (Amat y León and Pérez Guadalupe, 2018, p. 410) would be distinguished from Pentecostals by attracting people who aspire to climb the socioeconomic ladder (Prosperity Theology), by not adopting ascetic or escapist behavioral norms, by not waiting for the second coming of Christ and seeking to build the kingdom of God on Earth ("theology of the present kingdom"), and by its great interest in politics, among others (Ihrke-Buchroth 2013: 60)13.

Prosperity Theology: divine justification in the secular

In the literature reviewed, it is possible to find several somehow equivalent terms that tend to highlight particular points of this approach. For example, it can be mentioned as the "theology of the American dream", referring to a theology functional to American geopolitical and economic objectives (Spadaro and Figueroa, 2019, p. 248); as the "theology of individual success", which finds in Prosperity Theology a mercantile function that justifies material well-being as a product of divine grace (García-Ruiz and Michel, 2014, pp. 5-6); as "theology of the present kingdom", which seeks to build the kingdom of God on Earth through a postmillennialist eschatology (Ihrke-Buchroth, 2013, p. 60); or, as "neo-Pentecostal theology", which would have as its ultimate goal the spiritual salvation, physical healing and material prosperity of its faithful (Rodriguez, 2007, p. 93).

This theology is understood as the affirmation of "a direct relationship between communion with God and material well-being" (Tec-López, 2019, p. 39). This link between the sacred and the profane would come, according to Spadaro and Figueroa, from the fact that these evangelicals consider themselves the spiritual children of Abraham, "children of the King", which would grant them a series of material rights (2019, p. 274). In that way, "sowing" and "harvesting" would be metaphors interpreted economically in terms of "return on investment" (Spadaro and Figueroa, 2019, p. 274). This would be possible because, unlike the Protestants of the Reformation, who did not believe in the penetration of the divine in the worldly, for Neo-Pentecostalism, there would be "an effective penetration of the divine in the soul" (Sánchez Paredes, 2005, p. 94) which would mean that "God intervenes directly in the world and in his faithful to help them in their salvation [or prosperity]" (Sánchez Paredes, 2005, p. 94)14.

Religion and Politics in the Neo-Pentecostal Movement

The studies by Pérez Guadalupe (2017, 2018) and Amat y León and Pérez Guadalupe (2018) show that the evangelical political participation that currently leads the Neo-Pentecostal movement has not been able to materialize into a tangible political force. This is because, as both authors say, there is no "confessional vote"; that is, Christians does not necessarily vote for Christian. However, this does not mean that their political participation has decreased. Although until before the last presidential elections in Peru, the moral agenda of these groups has not been successful in formal politics through the formation of political parties, the "evangelical politicians" have found in the conservative social movements a fairly loyal niche that helps them to position their issues in the national political agenda. In the last presidential elections, this produced political gains for them through the ultra-conservative Renovación Popular party.

In this context, the "religious anthropocentrism" (Amat y León and Pérez Guadalupe, 2018, p. 243) of Prosperity Theology adopted by Neo-Pentecostalism would have implications for the relationships it constructs with the social, economic and political spheres. The idea of being the "children of the King" would not only situate Neo-Pentecostals as the legitimate heirs of the spiritual and material blessings that God grants to his faithful followers but would also place them in a privileged position vis-àvis those who have not yet experienced the gift of the Holy Spirit through conversion. These notions would facilitate the identification of this Other and their placement on an inferior plane that has to be countered (or fought) through evangelization and political participation. Although at the beginning, the political participation of these groups was incipient, the growing conservatism of Protestants, their moralistic reaction to secularization (Sánchez Paredes, 2005, p. 104), and their desire to transform the world based on a theology focused on material usufruct, made the political participation of these groups urgent to gain political power and execute their moral agenda.

In this regard it is interesting to mention the idea of "Nation" as a Church of Rubén Lores (1987, pp. 15-16, in Fonseca, 2002, pp. 75-76). He argues that due to the U.S. American religious plurality, the Nation took the place of the Church with the objective of, among others, fulfilling and enforcing God's designs (Lores, 1987, pp. 15-16, in Fonseca, 2002, pp. 7576). Just as in the "evangelical politicians", the religious is placed above the political. This idea of the Nation would place the religious above the secular in all aspects of society. Under this religious concept of Nation, it is not surprising to read expressions such as those of Edir Macedo, a Brazilian pastor, about a ""nation project" elaborated by God [that] is concretized in a "project of political power"" (Pérez Guadalupe, 2018, p. 57).

The social, economic, and political aspects of Neo-Pentecostalism

Both the idea of the Nation-Church of Lores and that expressed by Edir Macedo point towards an extension of the religious in the secular plane. This "national-evangelism" (Kourliandsky, 2019, p. 144), in that way, would try to meddle in the social, the economic, and the political with the aim of fulfilling the objective set for them: to prepare the ground for the arrival of the King and, in that process, to benefit from the material usufruct product of the deposited faith.

In the social sphere, it is possible to see an individualistic approach to the world, a posture that can also be seen in their religious perspective: "first one has to save oneself to save others". As García-Ruiz and Michel say, there is a preference for the individual, over the community, since it is considered that the transformation of the individual is a requirement for a transformation of society to be generated (2014, p. 6). Furthermore, Neo-Pentecostals' relationship with the world would be based on a "rigid morality" (García-Ruiz and Michel, 2004, p. 6). Thus, Neo-Pentecostals would see themselves as combatants in a spiritual war (Pastor Gómez, 2018a, p. 61), where the evil of the world is characterized through abortion, homosexuality, pornography, the destruction of the "traditional family", "gender ideology", social liberalism, among other values and practices influenced by Satan.

Economically, Prosperity Theology would have been the religious justification for its followers to seek to enjoy material usufruct in their life on Earth. This would be in concomitance with an individualistic conception of salvation that manifests itself with an "ego-centered" posture expressed in "I save you, but to save me". This individualism would also be expressed in economic terms since the search for wealth would fall solely on the believer. Thus, economic success, or lack thereof, would be closely related to faith and devotion to God. It can thus be seen that "mercantile logics and the logics of belief do not intertwine, [but rather,] overlap in substitution" (Mardones, 2005, p. 109).

This overlap has led several scholars of this phenomenon to establish links between neo-Pentecostalism and neoliberalism (Kourliandsky, 2019, p. 144; Spadaro and Figueroa, 2019, p. 248; Pérez Guadalupe, 2018, pp. 29-30, 45; Bergunder, 2009, pp. 22-23; Rodríguez, 2007, p. 90; Ribeiro, 2007, pp. 55-56; Mardones, 2005, pp. 104-105, 110). Even to assert that the former favors the expansion of the latter. However, it is important to emphasize that this link does not mean that Prosperity Theology finds in capitalism the manifestation of the Kingdom of God (Ribeiro, 2007, p. 56), but that it is in line with the neoliberal logic that "contributes to the association between consumption and salvation, between capitalism and the Kingdom of God" (Ribeiro, 2007, p. 56).

Finally, politically, the Neo-Pentecostals have "the conviction that God has commissioned them to conquer political power and, from there, to direct the destinies of the nation, according to the religious morality that he tries to position as valid criteria for the whole country" (Amat y León and Pérez Guadalupe, 2018, p. 410). The presence of the "political evangelicals", whose main slogan is based on the defense of a "rigid morality" that they want to impose on the whole country, is what Kourliandsky calls of "national-evangelism" (2019, p. 144). A clear example of this would be Jair Bolsonaro's emblematic phrase "God above all". This defense would be a ""moralistic reaction" against [a] secular ethic that promotes forms of conduct, thought and life devoid of religious meaning" (2005, p. 104) and would correspond to a theological approach that considers that a "spiritual war" has been unleashed (Masferrer, 1998, p. 9, in Jaimes, 2012, p. 656) since society would be "a square taken over by Satan and his hosts against which a "spiritual war" must be deployed to expel the demons" (Sánchez, 2005, p. 86).

Weber and Neo-Pentecostalism in Latin America

One of the characteristics that Weber points out of the Protestants of the Reformation is their "puritan asceticism". This asceticism implies an ambiguous relationship with the world: one is inserted into it but distances oneself from it. As Weber mentions, work, as a "calling", would be the means by which God is glorified since it is the "vital purpose of existence, by God's command" (1991, p. 94). Nevertheless, not all work fell into this category. In order to please God, the Puritans of the sixteenth century considered that work had to follow certain ethical criteria, benefit the community and provide economic returns to the individual (Weber, 1991, p. 97). However, due to their strong asceticism, their repudiation "against "carefree" pleasure [...] and licentious enjoyment of life" (Weber, 1991, p. 100), and that the human being "is but a steward of the goods" that God has given him (Weber, 1991, p. 102), the enrichment resulting from work should not be destined to satisfy frugal desires, but to honor God (Weber, 1991, p. 97). Hence, according to Weber, the "Protestant ethic", expressed through a tendency towards saving and reinvesting accumulated capital, was an important point in the development of capitalism. As Sánchez Paredes says, this was "one of the factors on the basis of which the attitude of discipline that the Protestants assumed [...] and which will lead them to the formation of the spirit of hard work and the accumulation of money [to] glorify God" (2005, p. 89).

A starting point that is sometimes overlooked from a strictly Weberian reading and that both Sánchez Paredes (2005) and Ihrke-Buchroth (2013) mention is, in the words of Sánchez Paredes, that "the [Peruvian] religious, cultural and social frameworks, [...] are certainly not the same ones that Weber studied" (2005, p. 85). This distinction of frameworks is important because, while the "predestined" of the sixteenth century found in work a means "to achieve grace and personal salvation" (Sánchez Paredes, 2005, p. 98); the Pentecostals of countries like Peru find in work a means to survive; therefore, what is really important to them is spiritual wealth (Sánchez Paredes, 2005, p. 99). In this sense, Pentecostals, unlike Protestants, possess "a rationality that is more religious than economic" (Sánchez Paredes, 2005, p. 95).

Unlike Pentecostals, Neo-Pentecostals tend to be found in middle and upper socioeconomic sectors and are characterized by a desire to move up the social ladder; therefore, their relationship with the sacred and the profane is different. However, Neo-Pentecostals are not always found in these socioeconomic sectors and, therefore, are not always able to express such displays of material blessings. In Neo-Pentecostalism, it is not possible to find the same vision of the function of wealth that the Puritan ascetics of the sixteenth century had: that of reinvestment of capital. As mentioned by Sánchez Paredes (2005, p. 99), the context in which Latin American evangelicalism develops situates work not as a means-to-produce-capital but as a means-to-survive. That is why, although economic promotion and success are important elements for the Neo-Pentecostals, the lack of both would not present any problem for their believers since, as Ribeiro mentions, the economic mobility promoted by savings and an ascetic life of the Weberian thesis is transferred from the economic spectrum to the "religious and imaginary spectrum of the faithful" (2007, p. 55).

Studying conservative groups on Facebook

The onset of the global outbreak of COVID-19 forced the research to change its methodological approach. From a "traditional" ethnography, I moved to a digital ethnography15. Due to the preferential use of Facebook in Peru16, it was decided to work on that platform; and, along those lines, with the Facebook groups of these collectives, focusing on the participation of their members in these forums. In this way, surveys (and an interview) were conducted; in addition, users' comments in Facebook groups were observed, as well as the "Like" sections of some profiles.

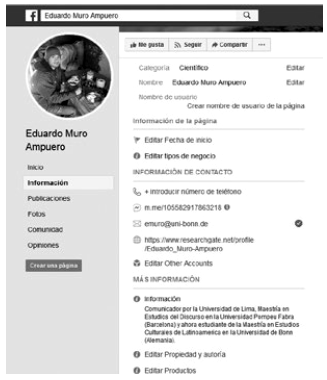

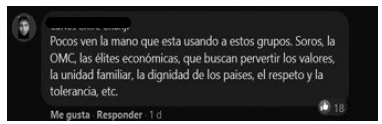

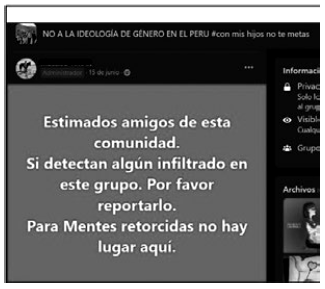

In this regard, it is crucial to mention that the groups studied here have a hermetic character (see image 1). This could be because their members perceive themselves in a spiritual war. In that sense, as a social researcher with leftist political tendencies, how to approach these people without being perceived as the "enemy" was a constant concern that was reflected in the methodological strategies.

IMAGE 1 Dear friends of this community. If you detect an infiltrate in this group. Please report him. For perverted minds there is no place here17.

This type of reactions forced the creation of a researcher profile (see image 2) and to participate with it in several conservative groups on Facebook. This also had an impact on the fieldwork. Initially, it was planned to carry out a participant observation; however, the reaction of the users was null. Therefore, only Facebook groups and profiles will be observed. In addition to this, there was slight predisposition to participate in an investigation about them -only one could be carried out but to one of the co-founders of CMHNTM. For this reason, surveys were conducted that attempted to approach the depth of an interview. Out of more than one hundred people, only twelve answered the questionnaire18.

What society do followers of Peruvian conservative groups on Facebook want?

Conservative groups such as CMHNTM enter the political arena with the objective of confronting the Peruvian State's responses to the demands of feminist and LGBTI+ groups (Tello Aguinaga, 2019, p. 14). This position has a religious substratum that focuses on the central role of the "traditional family" in society. From there, it is not only subtracted how a family has to be, but also what are the accepted behaviors and moral values for this type of family to flourish and be protected. However, these movements are not only limited in their approach to issues of sexual diversity and the defense of the monogamous heterosexual family but also project through their demands an ideal of society: socially, politically, and economically.

In the social sphere

For most people surveyed, the values that should be cultivated in Peruvian society are honesty, solidarity, justice, respect for others, and the defense of the "traditional family". The importance of the latter lies in the fact that it is the "basis" of society and that it is there that the moral values that will ensure the existence of new generations are cultivated (SR119, Protestant man, 25-39 years old)20. The constitution of this by a father and a mother is seen as a diverse and complementary aspect in the family (SR2, evangelical woman, 25 to 39 years old), where the "natural" roles of each one are of utmost importance for the future of the children and society (SR3, evangelical woman, 18 to 24 years old).

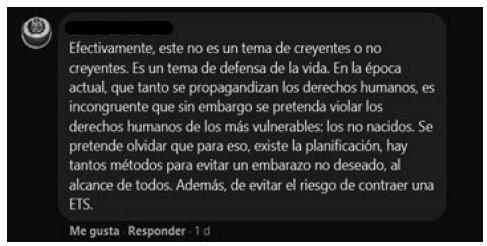

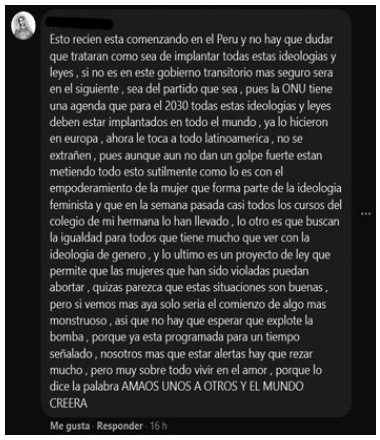

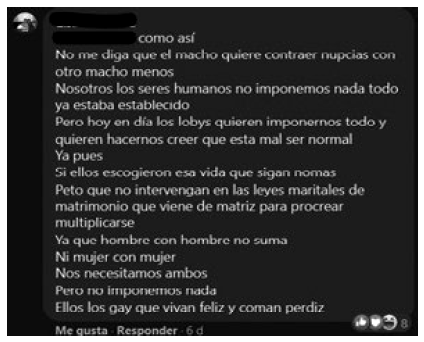

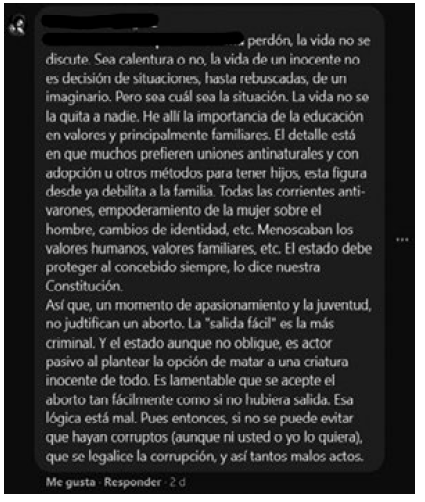

The ideologies21 that threaten Christian principles and the constitution of the "traditional family" are "gender ideology", "pro-abortion ideology", and communism (socialism and progressivism). Regarding "gender ideology", it is said that it transgresses the "divine natural order" (SR2, evangelical woman, 25-39 years old). Likewise, it is highlighted that this ideology places women as the victims, "seeking to place women in a top position only because of their sex" (SR3, evangelical woman, 18 to 24 years old). In addition, because this ideology promotes homosexualism and lesbianism by teaching "the little boy who is in formation, that he needs to have the image of man and woman, [...] that there is a third sex and even a fourth and a fifth. And that he can choose what he wants" (personal communication with the co-founder of CMHNTM). Regarding abortion, it is mentioned that life is a gift given by God and that these would obey selfish and evil agendas (SR2, evangelical woman, 25-39 years old) and would be in contradiction with the "human rights of the most vulnerable, the unborn" (image 3). Finally, communism and other leftist positions22 would go against Christian principles because they "deny the existence of God and the ultimate work of his creation (man and woman)" (SR3, evangelical woman, 18-24 years old) and because they "encourage disrespect, both for thought and for the property and well-being of others" (SR4, Roman Catholic man, 25-39 years old).

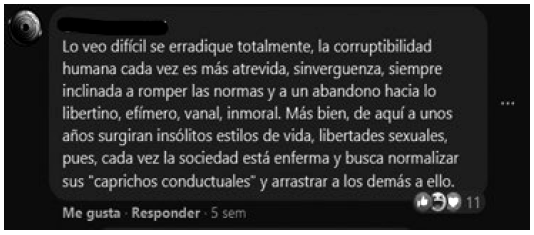

The aforementioned would place them in a reality that is gradually moving away from Christian values and reason (image 4), and where the presence of "human corruptibility" is growing, "always inclined to break the rules and to an abandonment towards the licentious, ephemeral, banal, immoral" (image 5). In this context, what Peru would need to improve as a country is more education, the promotion of entrepreneurship, more respect for citizens' rights, and decentralization of the State. Only half of the respondents voted in favor of the fight against violence against women -even less in favor of the fight against violence against sexual minorities.

In the political sphere

The perceptions of the members of these groups about Peruvian society transcend the social sphere and are reflected in political preferences and interests. For example, for most of those surveyed, the family should have the most important place in the State's public policies. On the one hand, because public policies in other areas (education, health, defense, among others) would have direct effects on the family; and, on the other hand, because a strengthened family would transmit the values that society needs. This strengthening would help to put an end, for example, to current problems such as corruption, since it "starts at home" (SR5, Mercedarian Catholic woman, 25-39 years old). Along these lines, one participant noted that the State should be based on Christian values since "one of the central commandments [is] love your neighbor as yourself" (SR6, evangelical woman, 18-24 years old).

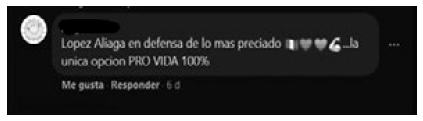

For the followers of these groups, the family plays a central role. This is also reflected in the Facebook pages that some users follow. Among them are not only pages of religious organizations and movements according to each user's preference, but also pages of social organizations in favor of the defense of the "traditional family", against "gender ideology" and abortion ("Movimiento Vida y Familia 2.0", "Perú Defiende la Verdad", "La Familia Importa -Perú", "Cruzada Nacional contra el Aborto"), pages of organizations and political parties of the most conservative right wing in Peru ("Renovación Popular", "Coordinadora Republicana", "Acción Cristiana", "Fuerza Popular") and of the liberal right wing ("Podemos Perú", "Juventudes PPK [Pedro Pablo Kuczynski, former Peruvian president]", "Derecha Alternativa Libertaria", "Coalición Libertaria") and, along these lines, pages of national and international politicians and public figures ("Team Trump", "Ben Shapiro", "Mitt Romney", "Jair Messias Bolsonaro", "Rafael López Aliaga", "Alberto Fujimori", "Keiko Fujimori")26.

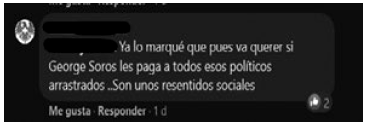

The development of the type of family that these groups advocate, however, would be undermined by two factors: external influences on the Peruvian political agenda and leftist political stances. One person who is constantly mentioned in Facebook comments and literature is George Soros (image 6 and 7)27. This billionaire and philanthropist is seen as an agent who plays an important role in international politics because he "finances communist ideologies throughout the West" (woman with no religious affiliation aged 18 to 24) and because he is part of a "global agenda [...] of population reduction" (SR2, evangelical woman, 25-39 years old) or of a "global purpose" that financially supports the "feminist movement, abortion and gender ideology" (SR3, evangelical woman,18-24 years old).

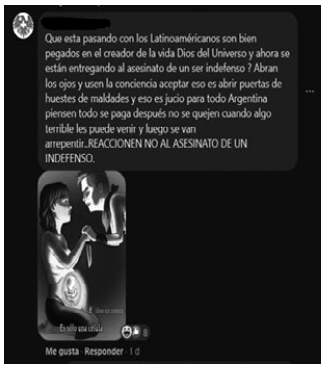

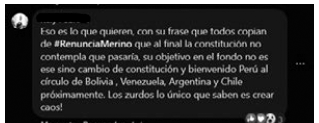

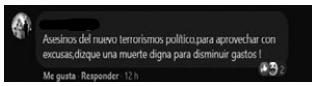

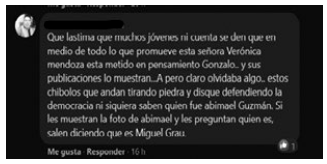

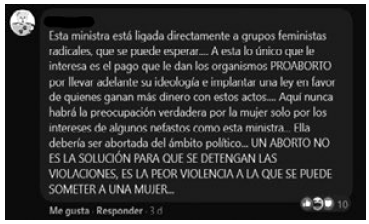

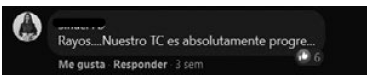

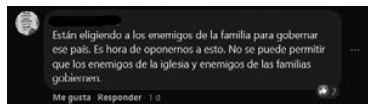

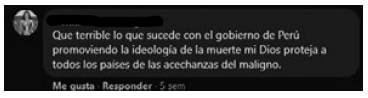

Leftist positions, on the other hand, are seen as ideologies that threaten life (image 8), Christian principles (image 9) and are spreading throughout the region (image 10). As mentioned by the co-founder of CMHNTM, communism or the left destroys the minds of young people (personal communication). According to one of the Facebook comments, this rejection was due to the still current association between leftism/progressivism and terrorism (image 11), especially the era of terrorism experienced in Peru in the 1980s (image 12). This was also reflected in the "Like" section of the Facebook profiles reviewed for this research: anti-progressive or anti-leftists' pages such as "Abogados antifeministas", "Manifiesto Anticomunista", "Mujeres AntiFeministas"; and, anti-terrorist pages such as "Peru contra el terrorismo" and "Terrorismo Nunca Más Perú".

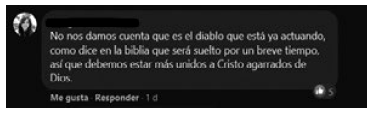

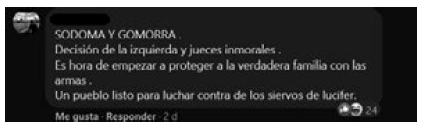

In addition, there is an international network that pays left-wing and liberal politicians to promote "unnatural" public policies (image 13 and 14). Along these lines, the criticisms of Facebook users focus on the fact that the government and the current political class are "absolutely progre[sive]" (image 15), "enemies of the family" (image 16), that they are "promoting the ideology of death [gender ideology]" (image 17) and that all this is a reflection that "the devil [...] is already at work" (image 18). Hence, some users make a call to oppose "the enemies of the church and enemies of families" (image 16), support the former presidential candidate from the ultra-conservative party Renovación Popular, Rafael López Aliaga (image 19), and even take up arms to "protect the true family [...] from the servants of Lucifer" (image 20).

In the economic sphere

The importance of the State defending Christian values is not only in its moral and political repercussions but also in its economic ones. This is because "[m]any of the countries that are developed countries today [i.e. the United States and South Korea], come from nations with Christian foundations and values [and that a] society based on biblical principles will be fruitful and blessed with more order, honesty, integrity, generosity, respect, and love" (SR2, evangelical woman, 25-39 years old).

In this context, a question was asked about the role of the State in the Peruvian economy and the best way out of poverty. Regarding the first point, there are two positions worth highlighting. On the one hand, it is considered that the "state should have little or no control over the economy" (SR7, woman with no religious affiliation, 18-24 years old) and be open to the free market, allowing "free competition between national and foreign companies" and forgetting "subsidies" (SR4, male Roman Catholic apostolic Marianist, 25-39 years old). On the other hand, some importance is attributed to the role of the State in the economy. In general terms, it can be said that the State should always seek "what is best for the citizens" (SR8, evangelical man, 40 to 70 years old) since the economy "provides us with stability [and] the guarantee of peace of mind for our family" (SR9, Mercedarian Catholic woman, 25-39 years old). In this sense, reference is made to the support that the State should provide to small national businesses and entrepreneurs (SR3, evangelical woman, 18-24 years old).

On the second point, i.e., how a person can get out of poverty, there was an emphasis on the individual, on the effort "necessary to get ahead", by working and entrepreneurship (SR10, Catholic man, 25-39 years old), "[e]ither formally or informally" (SR4, Roman Catholic man, 25-39 years old). Along these lines, I found in the "Like" section of some users pages that focus on entrepreneurship, personal and financial success. Apart from finding pages of Start-Ups, pyramid businesses and public figures that assume the role of coaches, pages such as "Soy Exitoso y Millonario", "Emprendimiento Mundial", "Líderes Creativos de Perú", "Éxito y Prosperidad", among others, were found. In addition, some pages combine entrepreneurship with religion: "Católicos emprendedores", "Cristianos Que Emprenden", to give a few examples.

However, some respondents believe that the State should also play a role in helping people escape poverty (SR2, evangelical woman, 25-39 years old): the role of the State should not be limited to supporting entrepreneurs but also to "[i]mproving the quality of state and university education" (SR4, Roman Catholic man, 25-39 years old), "educating about finances in public and private schools" (SR1, Protestant man, 25-39 years old), and creating "laws that benefit the worker" (SR6, evangelical woman, 18-14 years old).

Discussion

This chapter aims is to engage in a reflective dialogue with the results. During the development of this work, I have been able to appreciate different aspects of this phenomenon that one can link to previous studies; however, the novel character of this research has also brought aspects that have not been found elsewhere. It is worth mentioning that due to the exploratory character and the objectives of this work, it is natural that certain aspects are not commented on43. On this point, I hope for the reader's understanding.

Neo-Pentecostal political theology and "pro-life" and "pro-family" conservatism

In the social sphere, the "rigid morality" of which García-Ruiz and Michel (2004, p. 6) speak would be expressly manifested in the positions adopted with respect to lobbies and the LGTBI+ agenda (image 21), the distancing from Christian values and reason (image 4) and against samesex marriage (image 22), but, above all, in the comment in image 23, where it is made very clear that these Facebook spaces do not accept debate. There is no interest in engaging in a dialogue or generating a space that encourages the confrontation of ideas (another example of this can be seen in image 1). In this sense, we can ask ourselves, how would it be possible to engage in a dialogue with those people whom we consider that they threaten the basis of society, namely, our notion of family? Regardless of how the term "family" is conceptualized, I believe that this question -often overlooked- is an extremely important element in order to understand the moral rigidity, hermeticism, and reaction of these conservative groups.

From Prosperity Theology and studies on Neo-Pentecostalism, an individualistic -or, as Sánchez Paredes (2005, p. 92) says, "ego-centered"- vision is alluded to since an "indispensable condition to save oneself [is] to help save others" (Sánchez Paredes, 2005, p. 92). However, I believe that this evangelizing notion would not be extrapolated to what is observed in conservative groups since they would not seek to convert but to defend society. In the first place, although it may seem insignificant, because of the importance of the family as a social unit and support of the social fabric. Secondly, because of the sense of community built in social networks such as Facebook, not only in pages such as those studied here but also in private groups created mainly to coordinate, organize and inform about different aspects of the movement. In addition, the review of the "Like" section shows how these are taking shape and that they are not limited only to "pro-life" and "pro-family" issues but are transversal at different levels (political, social, and economic). Finally, although the followers of these groups on Facebook are not all religious, it seems to me that it is important not to overlook the role that religion could play in generating community. The latter can be seen, for example, in the large presence of pages of religious communities and organizations seen in the "Like" section of several profiles.

Economically, unlike the previous point, the "ego-centered" stance here would be quite visible. In the "Like" section, pages focused on entrepreneurship could be seen regarding the economic aspect. The presence of pages such as "Soy Exitoso y Millonario", "Éxito y Prosperidad" or "Cristianos Que Emprenden" would ratify a close, but not direct or causal, relationship with Prosperity Theology, also called "theology of individual success" (García-Ruiz and Michel, 2014, pp. 5-6). In that way, a relationship would be established "between consumption and salvation, between capitalism and the Kingdom of God" (Ribeiro, 2007, p. 56). This is clearly expressed in the quote from a female evangelical participant when she says that "[a] society based on biblical principles will be fruitful and blessed with more order, honesty, integrity, generosity, respect, and love" (SR2, evangelical woman, 25-39 years old).

However, among members of conservative groups there is a strong emphasis on the fact that the only way out of poverty is through individual effort (entrepreneurship) and that some advocate the deregulation of the economy and its unrestricted opening to the world market; there are other voices that recognize that the State has a role to play in this regard, especially in the just defense of small national enterprises. Although this is not entirely aligned with what is proposed by the political theology of neo-Pentecostalism, neither does it contradict it since these voices are mostly maintained only at an economistic level.

In the political sphere, the results highlight a topos that establishes a direct relationship between "good" and "Christianity" and, failing that, between "evil" and "progressivism" -although many times throughout this work it has been seen that words such as "progressivism" or "ideology" are emptied of their traditional meaning. Along these lines, one participant mentioned that the State should take Christianity as its foundation since one of the central commandments is to love one's neighbor as oneself (SR6, evangelical woman, 18-14 years old). Furthermore, the defense of Christianity as a model to follow is not only due to its moral "superiority" but also because it has proven to be the religion that favors the economic development of a country (SR2, evangelical woman, 25-39 years old). This is quite visible if we observe the number of conservative pages of "Organizations and political parties" and "Politicians and public figures" that appear in the "Like" section, but above all in the political preferences for the 2021 presidential elections, which fluctuate between neoliberalism and ultraconservatism -as long as these are positioned against the "gender approach".

From there, we can rescue two aspects that are central in the political theology of Neo-Pentecostalism: the idea of "Nation" as Church and the role of morality. On the one hand, we would have the consolidation of the "great project of nation intended by God" (Macedo, 2008, p. 112, in Pérez Guadalupe, 2018, p. 57) a conception of Nation subordinated to the religious. On the other hand, morality, as was seen lines above, is the element around which the great majority of approaches revolve, not only of the neo-Pentecostals, nor of the most conservative wing of Catholicism, but also of conservatives in general. The fact that this aspect has increased in such a way that it has divided Peruvian society is due to the fact that it is reacting "in the face of [a] secular ethic that promotes forms of conduct thought and life devoid of religious meaning" (Sánchez Paredes, 2005, p. 104). Hand in hand with the idea of Nation as Church, then, it would be seen that the current society is "a square taken by Satan and his hosts" (Masferrer, 1998, p. 9, in Jaimes, 2012, p. 656).

In sum, it is possible to appreciate more similarities than differences between the political theology of Neo-Pentecostalism and the followers of the conservative Facebook groups analyzed here. Because the people who participate in these groups are different in nature, it is not possible for us to refer to them as a religious group; in that sense, we could not say that they possess stricto sensu a Neo-Pentecostal political theology based on Prosperity Theology. However, it could be affirmed that there is a religious substratum present in the justification of their defense of the "traditional family" and against abortion and communism.

Prosperity ethics on Facebook?

It is clear to me that the members of Peruvian conservative groups on Facebook cannot be compared as equals either with the Weberian proposal or with a contextualized reading of Latin American evangelicalism. However, this paper assumes that there is a close relationship and some influence of Neo-Pentecostalism in these groups (whether offline or online). Nevertheless, what is meant with "prosperity ethics"? First, I refer to Weber's Protestant ethics and the relationship between religiosity and capital accumulation and, second, to Prosperity Theology as a religious theoretical foundation that aligns the secular with the divine.

Sánchez Paredes (2005, p. 85ff.) mentioned that these are two different contexts and that the relationship between religiosity and work-savings-investment is not the same. On the one hand, the Puritan ascetics of the sixteenth century studied by Weber made use of work as a meansto-produce-capital; on the other hand, the socioeconomic context of the Peruvian evangelicals of this century would make use of work as a meansto-survive. A direct consequence of this would be that the latter possess "a rationality more religious than economic" (Sánchez Paredes, 2005, p. 95). This does not mean that Peruvian evangelicals have no relationship with the capitalist system (Fonseca, 2002, p. 181), but that values such as "work", "capital" and "investment" have a more spiritual function.

Based on the fact that among the members of the Facebook groups we found an "ego-centered" and entrepreneurship-based stance on economic issues, we can say the following: on the one hand, when we talk about the members of these groups on Facebook we are not talking about capitalist agents. With a quick review of the profiles (staging through general information, photos, and shared content) one can realize that they do not belong to the privileged classes of the country, but rather to the middle and lower socioeconomic sectors. On the other hand, due to the heterogeneity of people participating in these groups, one cannot directly speak of there being an ethic strictly based on a religious stance. This does not mean that there is no meeting point; according to one respondent (SR6, evangelical woman,18-14 years old), for example, there is a close relationship between development and being a Christian country. Whether this is due to divine predestination or to laboriousness is not something that can be answered in this paper. However, just as several authors mention the links between neoliberalism and neo-Pentecostalism (Kourliandsky, 2019; Spadaro and Figueroa, 2019; Pérez Guadalupe, 2018; Bergunder, 2009; Rodríguez, 2007; Ribeiro, 2007, and Mardones, 2005), I do believe that this close relationship responds to a type of religiosity that favors neoliberal expansion. It is enough to see the numerous presence of entrepreneurial pages in the "Like" section.

Finally, through the comments on Facebook and the pages found in the "Like" section, the preference for topics whose main emphasis revolves around (Christian) morality is quite clear. Morever, although they may not see themselves as the "children of the King" as in Neo-Pentecostalism, they see themselves as the defenders of moral values that they consider superior.

From these three points -that they are not capitalist agents, the heterogeneity of these groups and their emphasis on morality- we can conclude that spiritual-based morality plays a central role for these groups on Facebook. All this would move them away from a Weberian reading of an ascetic work-ethic as means-to-produce-capital. Thus, I agree with Fonseca (2002), Sánchez Paredes (2005) and Ihrke-Buchroth (2013), because the emphasis on the moral in the struggle of these conservative groups converts the material deficit into moral-spiritual surplus.

However, this does not mean that the economic aspect is left aside. The economic aspect is also present, especially when addressing issues such as material usufruct through entrepreneurship, the great problem that constitutes the left as a political-economic project and that this would threaten to change all spheres of society at the cost of destroying the neuralgic point of the social fabric: the "traditional family". As we have seen above, this would bring them closer to a "neo-Pentecostal ethic" than to a "Protestant ethic". However, I do not believe that we can speak of some kind of ethic -whether Protestant or Neo-Pentecostal- proper to these groups since the heterogeneity of their members does not allow us to reach such a conclusion, but this would not rule out that there are points of contact in the economic and spiritual aspects, both of which are akin to neo-liberalism.

Spiritual War 2.0

In the previous segment it was mentioned that in the political there are two elements to take into account: the idea of Nation as an extension of the Church and the function of a rigid and reactionary morality. From the point of Neo-Pentecostal political theology, the aim would be to constitute a "national-evangelist" project (Kourliandsky, 2019, p. 144). A marked tendency towards secularization of society would have generated that the advocates of this project see their objectives threatened. One of the main enemies, if not the main one, is the ghost of communism.

Although in the groups studied here, it is not possible to speak strictly of a "national-evangelist" project, there is a national project based on reactionary Christian values that are in clear confrontation with progressive forces, often dehumanized and personified as "hosts of evil". Like any war, the spiritual war in which conservative movements find themselves consists of different fronts of struggle. Facebook would be no exception.

When one enters the Facebook groups of these movements, one has the feeling of having entered a room whose atmosphere is tense. The images shared, the comments on the posts, and the profiles of the followers' accounts convey the feeling that everyone is on alert (see image 1). This is something that can be understood if we realize that these people feel that the media, the government, and its institutions, global organizations, and financial elites are against them. There is a clear sense of rebellion, but not just any rebellion, but one that has God on their side. Hence their hermeticism and the fact that they are always on the offensive, as demonstrated by a user calling to take up arms to "protect the true family [...] from the servants of Lucifer" (image 20).

In the case of the international political scene, it would seem that there is a hegemony whose influence is markedly communist/progressive and which would try through international institutions to impose its agenda on the whole world. It is curious, however, that for these people, communism is closely related to the global financial elite -as commented by the co-founder of CMHNTM (personal communication). In opposition, it is possible to appreciate a clear preference towards politicians and prominent figures of the conservative and ultraconservative right: Donald Trump, Ben Shapiro, the Spanish ultraconservative party VOX, Jair Bolsonaro, the current Hungarian government, Benjamin Netanyahu, among others. As mentioned at some point, this would operate as a dichotomous geopolitical reordering between progressive and conservative forces that, in some contexts, would take on discursive nuances similar to those of the Cold War.

The anti-communist, anti-left, anti-progressive, anti-feminist pages would express this disdain for opposing political, economic and social positions. This aversion is due to the fact that these ideals "contradict biblical principles" (SR1, Protestant man, 25-39 years old) and that, in the case of the contemporary left, because they would be the ideological heirs of the terrorist thinking that hit Peru in the 80s and 90s (image 12) -hence the term "new political terrorism" for positions in favor of abortion and sexual rights (image 11). Nevertheless, in addition, it is also because there is a lack of knowledge of what "ideology" really means and it is understood as an anti-scientific position -this distinction is very interesting since many of these people fall into dogmatism from their religious positions.

This subchapter shows the framework in which the members of these groups move. On the one hand, the review of the "Like" section has corroborated how these people shape their sense of community by following, in several cases, the same pages. In this sense, entrepreneurship, anti-communism, and the "traditional family" would be the three pillars on which their ideal of society is built, which they have to defend at all costs. On the other hand, in the comments, as well as in the survey and interview, it has been possible to find content that clearly expresses the tension in which the members of these groups find themselves. This type of polarization, which is based on fundamentalist language, contributes to the naturalization of a caricatured and diabolical vision that dehumanizes the political opponent. There is also a problem of discrediting public institutions, the media, and financial elites.

Some final considerations

The issue addressed in this paper is situated in the galloping rise of a conservatism that seeks to shape society according to the moral standards of a rigid, reactionary religiosity akin to neoliberalism. Specifically, this reactionary conservatism advocates the defense of the "traditional family", the fight against the homosexualization of children through the so-called "gender ideology", and communism -or, rather, everything to the left of the political spectrum. In this context, this exploratory work attempted to focus on the society's that conservative pro-life and pro-family groups desire for Peru. To do so, I took into account works such as that of Tello Aguinaga (2019), where the Evangelical-Neopentecostal religious affiliation of the spokespersons and promoters of these movements is highlighted. Bearing in mind that not all people adhering to these conservative groups on Facebook are Neo-Pentecostals, even Evangelicals, this research emphasized the (dis)connections between Neo-Pentecostal political theology and the conservative groups studied here.

Although this approach was useful for an exploratory work such as this one, it has limitations that have the effect that no general conclusions can be drawn. Nevertheless on the one hand, what could be observed is that the conservative Facebook groups exceed the Neo-Pentecostal vision, especially in the more spiritual aspect of Neo-Pentecostal political theology. On the other hand, as already mentioned, there are points of common ground such as, for example, "rigid morality", economic entrepreneurship, the idea of "Nation" as Church, and the feeling of being in the midst of spiritual war. I am of the opinion that these overlaps are not due to a causal relationship between the Neo-Pentecostal and conservative groups, but rather, since Peruvian society is still quite conservative and faithful, their objectives respond to similar ends. Along these lines, the use of a discourse that appeals to the "divine" (whether Catholic or evangelical) and that positions itself in defense of the "natural established by God" strengthens the feeling that its promoters fulfill a predestined role, which would reinforce the polarization between defenders and detractors.

Likewise, through the themes presented here, I was able to show that the moral-religious is like a halo that covers other spheres of society, such as the political, social, and economic spheres. However, to attribute all the explanatory weight to the moral-religious would be to disregard geopolitical aspects of the mid-nineteenth century that are of great interest for the present phenomenon studied. The beginning of U.S. imperialism and its relationship with a particular type of religiosity manifested through the Monroe Doctrine and manifest destiny, respectively, are a clear example of this.

However, to remain only in these comments would be stingy. To better understand these groups, it is also important to take into account their concerns. Leaving aside the defense of the "traditional family" and the homosexualization of society through the so-called "gender ideology", the members of these groups are concerned about health, education, poverty, corruption, and political representation. From their reading of society, all these problems could be solved if the "morality problem" or, rather, the lack of morality that plagues the world were confronted. Hence, they feel immersed in a "spiritual war" or as "soldiers of morality" and that their battlefront is the core of society, i.e., the family.

Another aspect that is of interest is the sense of belonging. As mentioned above, the conservative Facebook groups exceed the Neo-Pentecostal vision. To me this would imply that the religious sense of belonging would also be exceeded. This would be replaced by a greater and more encompassing one: the sense of belonging to a (digital) community that is defending the family and the most defenseless beings in our societies: children and the unborn. Not only is the sense of belonging to a group present, but also that of defending it from external elements (image 1). Furthermore, through the page preferences in the "Like" section, it is possible to appreciate how these people are interconnected: pages of entrepreneurship, anti-progressive, religious media, in defense of the "traditional family" and of life, among others. In my opinion, although not conclusively, this could give us clues as to what the profile of the followers of these digital communities would be like.

In sum, what this research leaves us with is a work that, despite being exploratory, brings us a little closer to this phenomenon and allows us to understand what is the ideal of a society that conservative groups such as those studied here would like for Peru. In my opinion, this desire, hand in hand with a reactionary Evangelical-Neopentecostal religious reading, makes their followers assume themselves to be in the middle of a "spiritual war" of a moral nature.